Bertrand Tavernier April 25, 1941-March 25, 2021

I don’t know if it’s a general effect of getting older, but these days I do seem to get more of an emotional impact from news of the death of someone who has been a part of my life for decades – that is, not a direct part as in knowing them personally, but rather an emotional and intellectual part through my experience of their work. But at the same time, I’m less inclined to note many of these deaths here in my blog, where I once felt some obligation to acknowledge the impact these people have had on me.[1] That said, I do feel a need to say something about Bertrand Tavernier, who died on March 25 at the age of 79.

I’ve been an admirer of Tavernier’s films since I first encountered them forty years ago, though I can’t recall now which came first – Death Watch, A Week’s Vacation (both 1980) or Coup de Torchon (1981). The range of content and tone displayed by these three films is, depending on your point of view, either impressive or the sign of a filmmaker who has not yet found his auteurist identity. And yet they do share something important in common: perhaps most simply put, Tavernier’s humanism, a deep concern with human character and relationships as these manifest in a wide variety of situations (and genres). This interest in people and a seeming disregard for distinctive stylistic stamps may make Tavernier seem old-fashioned, more rooted in an older kind of cinema than the self-conscious disruptions of the nouvelle vague. More Renoir than Godard, Tavernier displayed an emotional connection to the tradition contemptuously cast aside by so many of his contemporaries, a connection which led him to collaborate multiple times with screenwriters Pierre Bost and Jean Aurenche, who had their roots in the “cinema of quality” on which the Cahiers du Cinema critics heaped contempt before embarking on their new wave directing careers.

I haven’t seen all of Tavernier’s features, but of those I have seen the only really weak one is his foray into American movie-making, In the Electric Mist (2009), based on a James Lee Burke mystery novel, which apparently ran into problems with its distributor and was re-cut to some degree. In fact, for some reason Tavernier had long-running distribution problems in North America despite the critical success of Round Midnight (1986), with subsequent features getting spotty, belated distribution if at all. I had to wait years before seeing L.627 (1992), finally picking up an English-friendly Studio Canal DVD in Paris in 2010. In fact, I’ve had to rely on home video releases for both Capitaine Conan (1996) and Laissez-Passer (2002), two of his finest films, and have yet to see his three highly regarded historical features, La passion Beatrice (1987), La fille de d’Artagnan (1994) and La princesse de Montpensier (2010).

In addition to being a great director, Tavernier was also a critic and film historian, who ended his career with a huge documentary project addressing French cinema. This began with the dense, exhausting and seemingly exhaustive My Journey Through French Cinema (2016), which packs so much into 201 minutes that it’s impossible to absorb it all in a single viewing, but then he went on to expand on the project with a multi-part television series (just released on Blu-ray by Cohen Media Group; copy on order). Highly personal, this years-long project gave Tavernier an opportunity to restore those tossed aside by the nouvelle vague to a central place in French film history, in the process illuminating the influences which played such an important part in his own filmmaking. He represented a continuity in defiance of his contemporaries’ deliberate break with that history.

I was surprised to see this quality in his work receive some degree of criticism in a number of obituaries, where his films were referred to with words like “flabby” to describe his tendency to allow his characters to breathe by creating an expansive dramatic environment within which they exist on their own terms. It’s this approach which makes a film like Life and Nothing But (1989) such an emotionally rich, and devastating, meditation on the horrific psychological cost of war; it takes its time so that viewers can absorb every nuance of the characters’ experience. I also hadn’t been previously aware that Laissez-Passer, an account of French filmmakers who worked during the German Occupation, had been controversial for the sympathetic account if gives of the difficult moral choices faced by creative people in such a complicated political environment.

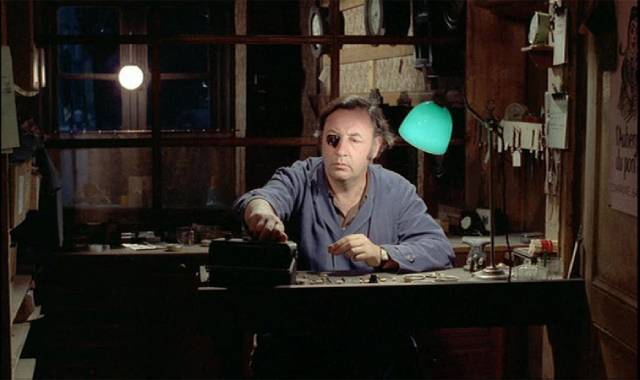

Among the films I hadn’t yet seen were three early features, including his debut, L’horloger de Saint Paul (1974), based on a 1954 novel by Georges Simenon. Correcting that oversight, I ordered a copy of Optimum’s Region 2 DVD. The disk has a decent standard definition image which is supplemented with a commentary by Tavernier and a 48-minute interview (both in English), both very engaging and conveying a sense of Tavernier’s influences and interests as a filmmaker.

The script by Tavernier in collaboration with Aurenche and Bost transposes the story from the States to contemporary France, adding a political dimension to its psychological study of the effects of a murder on the middle-aged protagonist, Michel Descombes (Philippe Noiret, in the first of eight roles for Tavernier). As is common in Simenon, the focus isn’t on solving a mystery – there is no mystery; we learn along with Descombes that his son has killed a man and fled with his girlfriend – but rather on the ways in which this act of violence causes the father to reevaluate his own life and what he thought he knew about his son. This process is facilitated through encounters with exploitative reporters and, more importantly, a sympathetic policeman, Commissaire Guilboud (Jean Rochefort) – a character who doesn’t appear in the novel.

Although there’s a murder at the centre of the narrative, this is a quiet character study which grows more emotionally resonant as it progresses, its climax being a moment in prison as Descombes talks to his convicted son Bernard (Sylvain Rougerie), perhaps for the first time as an equal, sharing an experience of his own in which he had a violent encounter with authority during the war. From seeming to have no knowledge or understanding of his son, here he discovers a connection suffused with a relaxed warmth which makes the terrible situation bearable for both of them.

Now I have to track down a copy of the apparently out-of-print DVD of his third feature, The Judge and the Assassin (1976).

Bertrand Tavernier April 25, 1941-March 25, 2021

__________________________________________________________

(1.) Tavernier was quickly followed by Richard Rush on April 8 and Monte Hellman on April 20, both 91. While their work didn’t have as deep an effect on me as Tavernier’s, both made films I’ve enjoyed and admired. Hellman was obviously influenced by the Nouvelle Vague – it’s remarkable that his two spare, existential westerns, The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind (both 1966) were produced by Roger Corman, and it’s hardly surprising that Universal didn’t know what to do with Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). As for Rush, his work was quite erratic, its roots in Corman-esque exploitation (Hells Angels on Wheels [1967] and Psych-Out [1968]), then veered into strained counterculture comedy (Getting Straight [1970] and Freebie and the Bean [1974]), after which there was a six year break before his masterpiece appeared – The Stunt Man (1980) remains one of the most exhilarating and exuberant love letters to the movie business even made, an endlessly inventive comedy which blurs the lines between fantasy and reality to a point where its hero plunges through madness to redemption. Strangely, despite its critical and commercial success, and multiple awards and nominations, Rush only made one other feature, and that fourteen years later; Color of Night (1994) got none of the love previously heaped on The Stunt Man, rather being derided as an embarrassing piece of trash. Personally, I liked it and still do, an overwrought erotic thriller which was made with the same kind of loving abandon as the earlier film. (return)

Comments