The subjectivity of watching: Bertrand Tavernier’s Death Watch (1980)

What we see when we watch a movie depends on many things … things which boil down to our own subjective experience – who we are and what we bring to the movie. Case in point: a recent evening when my friend Howard came over for dinner and a movie (or two). I always pull out a variety of disks from which to choose. I can watch each of them at any time, so I leave it to Howard to pick one he’d like to see. On this particular evening, among the choices was Bertrand Tavernier’s Death Watch (1980), a disk I hadn’t got around to watching even though I’d bought it quite a while ago (one of the drawbacks of being an obsessive collector).

I am a big admirer of Tavernier’s work. He’s a director with an enormous range of interests, to all of which he brings a powerful humanist sensibility – whether it’s the French Revolution (Let Joy Reign Supreme, 1975), American noir (Coup de Torchon, 1981), the terrible psychological consequences of war (Life and Nothing But, 1989; Capitaine Conan, 1996), harsh conflicts between the French state and the urban underclass (L.627, 1992), or the ebb and flow of daily life, past and present (A Sunday in the Country, 1984; A Week’s Vacation, 1980; It All Starts Today, 1999). His deep sense of film, of history, and of film history produced in Laissez-passer (2002) a richly nuanced evocation of the industry under German Occupation.

But Death Watch is something of an anomaly. It was his first film made in English (he has since made three more) and like Francois Truffaut before him, he chose a science fiction story for this foray into an alien language. (The film is adapted by Tavernier with David Rayfiel from a novel by the English author D.G. Compton.) It shares a number of characteristics with Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966), not least a slight awkwardness about the language. The characters don’t speak in an entirely natural way, although again this is in part due to the science fiction element – as in Truffaut’s film, dialogue at times consists of overt statement of themes, a degree of didacticism not found in the rest of either director’s work regardless of period or story.

While this can be perceived as a dramatic flaw, it also arises from the unique problem SF presents to a filmmaker: of necessity, the movie must create the details of an imaginary world. Finding a balance between merely presenting that world and hoping an audience will figure things out or, on the contrary, over-explaining everything can be a tricky business. In the case of both Fahrenheit 451 and Death Watch this is further complicated by the fact that in each the narrative itself has allegorical aspirations; SF is being used to explore certain philosophical concepts (I make no argument here for the profundity or lack thereof of these concepts – Ray Bradbury’s paean to the written word is heartfelt but rather naive; Compton’s prescient treatment of the media and the rise of what we now know as “reality TV” carries more weight).

Despite any perceived flaws, what I like about both of these movies is the way in which the filmmakers make use of existing locations to create a sense of some future, or at least other, world. This displacement of the present into an alternate narrative space can have the effect of making the viewer reassess what has been taken for granted and so to question deeply held assumptions about the nature of the present. Fassbinder did the same thing in World on a Wire (1973); even George Lucas did it in the original THX 1138 (1971), though his subsequent self-vandalism with massive CG revisions to that film has erased entirely what made it so effective in the first place.

Death Watch posits a future in which all death by disease has been eliminated; apart from accidents, people now fade away into age and dementia, sent out of sight and fed drugs which keep them calm and happy as they slowly slip away. But the absence of death has not created some kind of paradise; rather it has filled life with a kind of dull meaninglessness. Enter television producer Vincent Ferriman (Harry Dean Stanton), determined to give people back the emotional experience of death. His search for that rarity, a younger person suffering from a rare incurable disease, leads to Katherine Mortonhoe (Romy Schneider). The disease itself remains unspecified – all we and she know is that she has maybe a couple of months left to live.

Her condition, leaked by Ferriman, makes her an instant media celebrity. Going through the most painful and personal experience imaginable, she is suddenly forced unwillingly to do it in public. Harassed by the media, she finally signs an exclusive contract with Ferriman, but immediately after her husband collects the fee in cash, she slips away and begins a roadtrip across a depressed and occasionally violent landscape.

But Ferriman, having anticipated this, has a secret weapon – cameraman Roddy (Harvey Keitel), who has a television camera/transmitter implanted in his eye. Posing as another aimless traveler, Roddy connects with Katherine in the packed dormitory of a church mission. They establish a tentative relationship and travel together, his empathy offering her a degree of emotional support. The world they pass through is one of damaged urban spaces, dispossessed people, police violence and professional protests (marchers make their living being paid to carry signs against one social ill or another). There are passing references to wars and disasters which have damaged this society, but the use of actual locations ties the social decay to a depressed real-world present. Shot in and around Glasgow and the surrounding Scottish countryside, the film presents a world at the same time both strange and familiar; we already inhabit a future which we only partially comprehend. (The effect is a little like that in the later parts of Wim Wenders’ Alice in den Stadten [1974]; not coincidentally, Wenders’ Until the End of the World [1991] has many points of similarity with Death Watch; Wenders is reported to have said that both films were conceived during discussions between the two filmmakers.)

Although Tavernier gives Death Watch an atmospheric context of political and social exhaustion, setting the narrative in a beaten-down near future (or parallel present), the film’s power lies in its characters and the personal story it tells. Foremost is Romy Schneider as Katherine, a woman of strength and independence navigating a devastating situation with a mixture of grace, fear and determination. One of the finest actresses of her generation, she remains too little known. Her performance here is subtle, emotionally rich, and deeply affecting. Set against this, Harvey Keitel gives one of his more subdued performances as Roddy, a technician whose profession is detached observation, who goes through a gradual emotional and moral awakening through his interactions with Katherine. Harry Dean Stanton is his usual self, a slightly tawdry man full of self-assurance, ultimately incapable of comprehending the darker side of his own behaviour. And then Max von Sydow turns up in the final act to put the seal of gravitas on the film’s themes.

Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray presents the full, original European version of the film, not the shorter North American theatrical version (which was trimmed by 13 minutes). Other than a matter of drawing out various scenes, the biggest difference lies in an abrupt twist towards the end. (In deference to those who get upset by exposure to such details, I’ll offer a **SPOILER ALERT** here and suggest skipping the rest of this paragraph.) This twist comes as something of a throwaway, dropped into the dialogue as Ferriman and his team close in on Katherine where she has retreated to the remote house of her former husband Gerald (von Sydow). We suddenly learn that she is not, in fact, terminally ill, but has been manipulated by Ferriman and a complicit doctor; the drugs she has been given – ostensibly to manage her pain – are in fact the cause of her physical decline. Although this doesn’t materially affect her final decision to control her own fate, it adds a new layer of cynicism to the critique of media culture. But although this may be Tavernier’s preferred ending, it seems to me to be an unnecessary distraction from the main thrust of the narrative, which is so thoroughly rooted in the emotional and psychological effects of the situation on Katherine and Roddy. It also, in a way, undermines the authenticity of Ferriman’s moral bankruptcy by transforming him into a more sinister villain; this pulls the film away from what has until this point been a fairly astute critique of the ways in which media disrupt and distort reality by their power to manipulate and shape experience. Adding overt malevolence implies that things could be improved if better people were in charge. (**END SPOILERS**)

Anyone who has made it this far in my comments may be wondering what any of this has to do with my opening remarks about the unpredictability of personal responses to the movies we watch. It’s this: as I’m sure is apparent, Death Watch is a film I hold in fairly high regard. So it was a bit of a shock to discover when it was over that Howard felt a strong antipathy to it. This, it turned out, was partly explained by his comment that he doesn’t have much affection for science fiction as a genre, which made the film difficult for him to get into. He felt that it was dramatically stilted, with a number of poorly constructed scenes. I touched on the question of stiltedness above, a matter of needing to construct an unfamiliar imaginative world somewhat set apart from reality. Although he felt that Schneider was excellent as Katherine, he thought Keitel and Stanton were weak, particularly in the early stretches, where he thought they were merely reading their lines rather than performing them.

Exposition always presents a problem in movies, with actors required to supply necessary bits of information to the audience in ways which don’t necessarily reflect normal conversation. In a genre like science fiction this can be even more troubling than it is in, say, a detective story, because there’s often more than simple plot information at stake. But if you like a particular genre, chances are you’ll be far more forgiving; in fact, if you like SF, or fantasy, or horror, you’re likely to enjoy this aspect of the movie because it’s integral to creating the imaginary world and filling in the conceptual details. In fact, it sometimes even helps if such dialogue is somewhat banal because the banality reinforces the “normality” of the imaginative narrative elements.

Although Kubrick pushed this to an almost satirical extreme in 2001, the pedestrian dialogue in that film’s mid-section – on the space station, on the moon, and on board the Discovery on its voyage to Jupiter – emphasizes the ways in which anything may become mundane through familiarity and habit; having become used to space flight, the characters can no longer perceive how remarkable it is and only through Dave’s passage through the stargate and his transformation can that sense of wonder be reignited. All of which means that for me the banality of the dialogue between Roddy and Ferriman, and between Roddy and his estranged wife Tracey (Therese Liotard), adds to the impression of authenticity Tavernier gives to the film’s world.

Beyond this, I was surprised that, aside from the landscapes, Howard thought Death Watch was poorly photographed. The transfer on the Blu-ray is a vast improvement on earlier video presentations, with the atmospherically overcast Scottish exteriors richly saturated in various shades of green and blue. But it never occurred to me that the interiors were flatly lit and unimaginatively shot, and I wonder whether his impression here was at least partly influenced by his lack of engagement with the film on a dramatic level.

My biggest shock, though, came from his ambivalence to Tavernier as a filmmaker – I’d imagined he shared my admiration – particularly his confession that the antipathy he expressed for Death Watch extends to Coup de torchon, Tavernier’s adaptation of Jim Thompson’s 1964 novel Pop. 1280, which I consider to be a masterpiece. Given how much Howard and I share in our appreciation of films across a broad range of genres, periods and nationalities, I simply hadn’t anticipated his negative response. It’s hard not to feel a little personal disappointment when we share something we like and discover that the person we’re sharing it with rejects it. Naturally I’d never subject Howard to an Andy Milligan movie, as much as I enjoy the work of that crazed auteur – but I had every reason to believe that I’d be on safe ground with a master like Tavernier.

*

My Ain Folk (Bill Douglas, 1973)

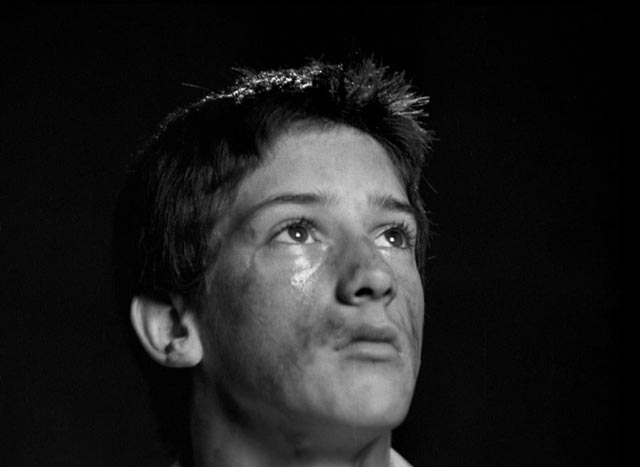

To take the curse off the evening, we ended by watching Bill Douglas’s My Ain Folk (1973), the second part of his autobiographical trilogy (and a very different view of Scotland from Tavernier’s version!). Howard had previously never seen the trilogy, and we’d watched the first part (My Childhood, 1972) a while back, so it seemed like a good way to decompress. My Ain Folk, a series of episodes told in a highly elliptical way through evocative tableaux interspersed with moments of wrenching emotional violence, is perhaps not as tightly constructed as My Childhood. Shot in richly textured black-and-white and performed with heartbreaking conviction by its amateur cast, along with My Childhood it presents one of cinema’s bleakest depictions of poverty and the forces which batter a child trapped in a family broken by deprivation.

There are echoes of the work of Terence Davies (in fact, the opening moments in which Jamie [Stephen Archibald] watches images from Lassie Come Home, an idealized Technicolor view of Scotland tragically distant from the boy’s own reality, evoke memories of Davies’ characters sitting in rapt attention in movie theatres), but for all the poetry of Douglas’s camerawork and editing, his view eschews the ways in which Davies revels in the contrasts between hardship and the liberation provided by various social pleasures which even the downtrodden working class can find – in movies, in music, in literature. In Davies, an active imagination can free one from hardships; in Douglas, despite the fact he grew up to become a masterful filmmaker himself, circumstances are too harsh to admit the possibility of liberation through an active inner life. Both directors are visual poets, but there’s a touch of the Romantic in Davies which is not apparent in the Douglas trilogy … although something of the kind did emerge in his sole feature, the magnificent Comrades (1986).

Comments

I felt the **SPOILER ALERT** was talking directly to me. I was deeply moved. **END SPOILERS** a nice touch, though I think the bold type should be bolder.

Of course, I had to read the alerted commentary.

I aim to please. We in the biz must listen to our fans!

I came across Deathwatch on Criterion Channel. It’s one of those films that seems built for processing and discussion — so hard to come by in this Covid era. That’s why a post-viewing internet search brought me here (Rotten Tomatoes was useless!).

Thanks for the analysis-by-contrast approach. I’m conflicted about Deathwatch, so my inner dialogue as I watched mirrored the one you had with your friend.

John Smith: Oh, where do I even start with Death Watch? This film had me glued to the screen from start to finish! Bertrand Tavernier’s masterful storytelling combined with the impeccable performances left me in awe. But you know what truly amazed me? The diverse range of reactions it evoked when I shared it with my friends. Some were intrigued, others puzzled, and a few even a bit conflicted. It’s fascinating how subjective the experience of watching a film can be. It’s like peering into someone’s mind and seeing the unique emotions and connections that are formed. So, hats off to Tavernier for creating such a thought-provoking piece. I absolutely loved it, and I can’t wait to dive into more films that challenge our perceptions and spark lively conversations!