Recent Arrow viewing, Part One: William Grefé

Since I’ve recently been aggregating comments about individual companies’ releases, I should mention a number of titles put out by one of my favourite labels: Arrow Video. Some of these I’m revisiting years after I first saw them, others are new to me, even though they’re older movies.

William Grefé

I took a chance when I ordered the new box set They Came from the Swamp: The Films of William Grefé. I’d previously seen three of Grefé’s features – Sting of Death and Death Curse of Tartu on a Something Weird double-feature DVD and Stanley from BCI – all ultra low-budget productions made in Florida and, to be honest, all pretty clunky. But they do have a certain drive-in exploitation charm. The carpet monster in The Creeping Terror may be jaw-dropping, but you ain’t seen nothin’ if you haven’t seen the jellyfish man in Sting of Death. These movies appeal to my taste for cheap regional features, but an entire box set? Truth is, it was the set itself rather than the movies it contains which attracted me, a lovingly prepared showcase for cinema trash. And yet it turned out to be much more, because Grefé, in addition to being personally charming, turns out to be a better filmmaker than those early horrors suggested and I enjoyed all seven of the films included (some more than others) as well as Daniel Griffith’s two-hour documentary survey of Grefé’s career which is included as the most substantial of the set’s many special features.

Born in Florida, Grefé was one of the first filmmakers to consistently make movies in the state, along with his contemporary Herschell Gordon Lewis. Unlike Lewis, however, Grefé didn’t start out with nudie movies; his first features were classic drive-in fare, The Checkered Flag (1963), about stock car racing, and Racing Fever (1964), which was built around a piece of documentary film showing the spectacular fatal crash of a high-speed boat racing champion. In 1966, three years after Lewis splattered the screen with Blood Feast (1963), Grefé took up the suggestion to make a horror movie; he didn’t follow Lewis’ lead, though, avoiding graphic gore and looking back to ’50s monsters.

*

Sting of Death (1966)

That first effort, written and shot very quickly, was Sting of Death (1966), a rather dull and extremely talky tale of an implausible group of college students on a research trip to the Florida Keys where biologist Dr. Richardson (Jack Nagle) is studying the local marine wildlife, assisted by Dr. John Hoyt (Joe Morrison), who is attracted to his boss’s nubile daughter Karen (Valerie Hawkins). The kids are more interested in hanging out by the pool and dancing to Neil Sedaka’s hit “Do the Jellyfish”, not to mention playing cruel jokes on the doc’s socially inept, scarred assistant Egon (John Vella). It’s not long before a monster emerges from the water and starts killing the kids.

The monster is a hoot – a guy dressed in an undisguised wet suit and flippers, adorned with a bunch of plastic tubing and an inflated plastic bag over his head. Yes, it’s half human, half jellyfish, and it’s not long before we discover that Egon has been performing his own experiments to prove that men and jellyfish can be combined … for some vaguely defined reason. In his transformed state, he gets revenge for all the slights heaped on him, and kidnaps Karen in hopes of winning her love. It’s a plan destined to fail tragically – a plan which plays out like a parody of dumb ’50s mad scientist/monster movies, though it seems that no mockery was intended.

*

Death Curse of Tartu (1966)

When Grefé presented the finished movie to a distributor, he was asked to make a companion film for a drive-in double-feature. Whipping up a script in a day and shooting in a week, he turned out Death Curse of Tartu (also 1966), the story of another group of students who, under the guidance of an archaeologist, go on a trip deep into the Everglades where they unfortunately disturb the grave of a long-dead native witch doctor named Tartu, who can manifest as various animals to exact his revenge on the intruders.

Like its predecessor, Tartu is dull, talky and filled with padding, but Grefé does make occasional good use of the swamp locations and airboats. There are attacks by a giant snake and an alligator (with some good behind-the-scenes anecdotes about the experiences of the cast with these wild animals), and the skeletal medicine man eventually returns to full human form for the final showdown.

Neither of these movies display any real feeling for the genre, which is why I initially didn’t have a very positive opinion of Grefé. That changed slightly when I saw Stanley (1972), which is not included in the set, something like Rambo with snakes, and obviously (and admittedly) inspired by the success of Willard (1971). A Native American Vietnam vet, tormented by locals, gets his revenge by using the snakes which are his only friends – a theme Grefé returned to later with one of his better films (which is included in the set).

*

The Hooked Generation (1968)

But before returning to horror, Grefé made several different kinds of films. I haven’t seen The Devil’s Sisters (1966), a fact-based story about Mexican serial killers, nor The Wild Rebels (1967), which began as another stock car movie but was quickly retooled into a biker movie after the success of Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966). Neither of these are included in Arrow’s set, which picks up with The Hooked Generation (1968), a very decent low-budget thriller which shows Grefé’s skills much improved since the horror double-bill.

With a better script and better actors, this is a fairly tight movie about a disorganized gang of drug smugglers whose big plans spiral out of control. Having set up a deal to buy drugs from the Cuban army (Castro apparently funds his revolutionary government with American dollars acquired by polluting the U.S. with dope), Daisey (Jeremy Slate), Dum Dum (Willie Pastramo) – named for his habit of doctoring bullets so they fragment on impact – and Acid (John David Chandler, a familiar face from westerns, including several by Sam Peckinpah) are put out by a demand that they pay double the agreed-on price. So they kill the Cubans, take the drugs, and blow up their boat.

Heading back to Florida, they’re spotted by a coast guard boat and dump the drugs overboard in a weighted sealed container. Daisey tries to bluff it out, but things go very wrong – first, a young couple on a nearby boat tell the coast guard they saw something being thrown overboard, and then Acid, who’s down in the cabin doing copious amounts of heroine, goes nuts and triggers a firefight which leaves all the coast guard crew dead and the young couple now hostages.

Pursued by the authorities, the gang try to sell the drugs to dealers who don’t trust them. Acid goes on a big trip with period-appropriate psychedelic effects, and it all ends in a messy showdown in the Everglades. With ramped up performances and a very grungy atmosphere, this is far more entertaining than the horror movies.

*

The Psychedelic Priest (1971/2001)

The Psychedelic Priest (aka Electric Shades of Grey) was made in 1971, but apparently not released until (according to IMDb) 2001. It’s a strange movie, very much of its time, which has the air of trying to make some kind of statement (though just what that might be is open to debate). Father John (John Darrell) teaches at a private school, where he tries to understand the kids and show tolerance for their transgressions. One day, stopping to tell a group on the lawn that he can smell the grass they’ve been smoking, one of them offers him a soft drink. What he doesn’t know is that it’s laced with LSD.

During the ensuing bad trip, he confronts God and, not receiving satisfactory answers, his faith crumbles. Throwing off his priest’s uniform, he hits the road and drives off in search of that lost faith. Like any road movie, there’s a ragged, semi-improv feel as episodes accumulate; John picks up a hitchhiker who is initially defensive (her last ride tried to rape her), but gradually falls for him. Along the way, they meet a bunch of hippies, aid in the birth of a baby overseen by a black doctor who dropped out after some time in Vietnam, and witness the worst of America (a couple of racist cops murder the doc just after John has persuaded him to resume his career).

When the woman declares her feelings for John, he flips because despite everything he still considers himself a priest and her temptation is an affront to that identity. Rejected, she slips away from their campsite; somewhat contrite, John tries to find her, even going so far as to hire a private investigator … but it turns out that she’s committed suicide. So, having contributed to two violent deaths, John somehow finds his way back to God and is last seen in full uniform talking to another group of kids at risk from drugs and the counterculture. It’s an odd, thematically murky movie – if we’re supposed to empathize with John’s spiritual struggle, it doesn’t work because he might have temporarily lost his faith but he still has a smug certainty of his own righteousness which turns out to be harmful to people who come near.

*

in William Grefé’s The Naked Zoo (1970)

The Naked Zoo (1970)

Also of its time is The Naked Zoo (1970), a sordid tale of the sexual revolution most surprising for its cast. This was almost the last film in which Rita Hayworth appeared (Grefé got her cheap by paying cash) and she gives a committed performance as Helen Golden, a wealthy woman married to Harry (veteran Ford Rainey, almost half-way through a five-decade career), who’s confined to a wheelchair; frustrated, she seeks sexual satisfaction from writer Terry Shaw (Stephen Oliver), who makes a living between books by taking money from rich women for sexual favours. An immoral creep, Terry walks out after Harry catches the two of them together and tries to shoot the gigolo, in the process falling out of his wheelchair and cracking his head on the fireplace.

With Mrs. Golden left to explain things to the police, Terry moves on to other opportunities while he’s worried about getting dragged into Harry’s death. Callous and unsympathetic, Terry eventually gets his comeuppance. But the film as originally released wasn’t the one Grefé made. After it was finished, the producer hired prolific exploitation hack Barry Mahon to spice things up – which he did by inserting a completely gratuitous nude scene (a woman playing with a vibrator takes a phone call from someone looking for Terry who isn’t there) and an equally gratuitous and unexpected appearance by Canned Heat, who ostensibly perform at a party where we never see them in the same shot with the characters and the characters seem oblivious of the band’s presence. There was also quite a bit of editorial fiddling.

Arrow have managed to reconstruct (mostly) Grefé’s original cut by removing Mahon’s additions and reinserting missing material from less than ideal sources. Most of the films in the set are quite battered, but this one may be the most ragged. The disk contains both cuts for completists.

*

Mako: Jaws of Death (1976)

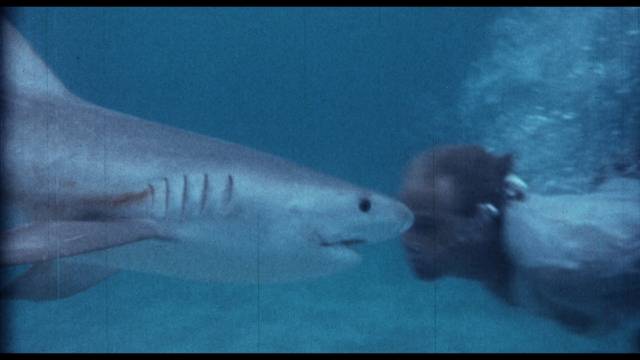

Apart from the presence of Rita Hayworth, the set’s biggest surprise is Mako: Jaws of Death (1976). According to Grefé, he wrote the script before Jaws was a gleam in anyone’s eye, but couldn’t interest anyone in the project until after Spielberg’s movie became a huge hit – which inevitably gave Grefé’s movie the appearance of a cheap knock-off. Of all the shark movies which were produced in the wake of Jaws, this may actually be the most interesting. Taking its cue from Grefé’s Stanley, it has Richard Jaeckel as Sonny Stein, a Vietnam vet who has a very special relationship with sharks; saved from the Vietcong by a shark, he’s later given a medallion by a Filipino man which forges a psychic bond between Sonny and the killer fish.

Unlike the other shark movies of the period, this one places its sympathy squarely with the fish, Sonny doing everything he can (including murder) to protect them from predatory humans. Unfortunately, that pretty much includes all humans. Betrayed by scientists studying the creatures as well as by the people running a Seaworld-like park, Sonny becomes pretty unhinged, but as he feeds various people to his friends, he remains sympathetic because his victims are thoroughly reprehensible.

Filmed, as the promo material says, without cages or special safety equipment, Mako has some impressive footage of people (including the actors) swimming among sharks. It also (paradoxically considering its message) has some grim real violence to the sharks.

*

Whiskey Mountain (1977)

Although it came a little late, Whiskey Mountain (1977) was obviously at least to some degree inspired by Deliverance (1972), a prestigious success which spawned a whole genre about city folks running afoul of backwoods people who are all too ready to use violence to protect their home turf. A pair of dirt bike racers head for the mountains of North Carolina with their wives for a vacation which also doubles as a treasure hunt; an ancestor of one of the wives helped to hide a couple of hundred Confederate muskets in a cave at the end of the Civil War and now they’re valuable collectors items.

When they ride into a small town, they’re greeted with hostility and warned to keep off the mountains (of course). But for them it’s just a fun trip … at least until things start to happen. Someone’s watching from the woods, stealing items (women’s underwear to add to the menace); they wake one morning to find the campsite surrounded by fire and only just manage to rescue their bikes. Eventually, they manage to reach the cave, but instead of muskets, they find garbage bags full of weed. The hostility is because there’s a gang of locals (led by John Davis Chandler) with a thriving grow op which supplies the East Coast mob.

Then things turn nasty as the two couples are held prisoner. Separated, the husband’s manage to escape and head for town to get help, only to find a very unhelpful sheriff (no prizes for figuring out why he refuses to believe their story). Meanwhile, the two wives are brutally raped. The men return with guns and there’s a bloodbath as they rescue their traumatized wives … though rescue is stretching things. It all ends on a very bleak note.

Once again Grefé had a good cast, headed by Christopher George, coming off William Girdler’s Grizzly (1976) and Day of the Animals (1977) and a couple of years shy of Lucio Fulci’s City of the Living Dead (1980), ably supported by Preston Pierce, Roberta Collins and Linda Borgeson, with Chandler excellent as the villain. While Whiskey Mountain is derivative exploitation, Grefé directs efficiently and at times with style (the visual restraint of his indirect treatment of the double rape makes it dramatically effective without seeming sleazily exploitative, and all the more shocking for that), making this one of the better films in the set.

*

Taken overall, He Came From the Swamp is an interesting showcase for a regional filmmaker who displays a degree of ambition within the limitations of low-budget exploitation, and increasing skill in his storytelling abilities. In effect, many of his movies were side projects, diversions from his day job of running Ivan Tors Productions, known for the TV series Flipper and Gentle Ben among others. He also took a long break from features as he spent years making promotional films for Bacardi Rum – twenty-five half hours from the late-’70s to mid-’80s. In Daniel Griffith’s documentary They Came From the Swamp (2020), Grefé comes across as pleasant and self-aware about what he was doing, with plenty of anecdotes about the problems of knocking out features in a few days with virtually no money.

As the survey of his career unfolds and you gain some appreciation for his accomplishments, it’s also a bit frustrating because some of the movies not included in the set look more interesting than some of the ones that are – in particular, The Devil’s Sisters and Impulse (1974), the latter starring William Shatner as a conman who preys on lonely women, stealing their money before killing them. That I’d definitely like to see!

In addition to the seven features and the documentary, there are numerous featurettes, new and archival commentaries, and a small hardcover book with advertising materials and excerpts from a 1999 career-spanning interview with Grefé by writer Chris Poggiali.

Comments

Thanks for understanding what we went thru making Films with little money and 7 to 15 days shooting time

Thanks for making the movies … I had a great time watching the set and am trying to track down the ones which weren’t included!

Thank you for interest in my Films

IMPULSE And Racing Fever will be on Blue Ray later this year

That’s good news – as a William Shatner fan, I’m very much looking forward to seeing Impulse!

Vinegar Syndrome have also just announced the first Blu-ray release of Mr. Grefé’s Stanley in May 2022.