Viewing notes, September 2016

I mentioned here a year ago that I was very disappointed with the Blu-ray edition of Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight released in the UK by Mr Bongo. Although based on a 2009 restoration by the Filmoteca Espanola, the quality of the disk was not much of an improvement on my old Spanish PAL DVD – print damage throughout, numerous scratches and flecks, and muddy sound, with brightness levels boosted so that contrast was flattened and blacks looked distinctly grey. While the new Criterion edition uses the same Filmoteca Espanola source, based on the original camera negative, the transfer has been cleaned up to remove all those signs of wear and lovingly mastered to provide a beautiful, sharp image with rich blacks and greatly increased detail. The work of Welles and his cinematographer, Edmond Richard, shines on this disk, finally providing the showcase Welles’ greatest film deserves. The sound is also much improved, with all that Shakespearean language now clearly audible.

In addition (as if this wasn’t enough to put the Mr Bongo disk to complete shame), Criterion have loaded the Blu-ray with two-plus hours of interview-based supplements and an audio commentary from critic James Naremore, in which he covers the original history, how Shakespeare used that history in his sequence of plays, and the decades-long efforts of Welles to forge a new work from the plays built around Falstaff, a character for which he felt a deep personal affinity.

The featurettes include an interview with actor Keith Baxter, who plays Prince Hal (29:49), in which he goes into detail about his experience working with Welles; an interview with Beatrice Welles, the filmmaker’s daughter (14:40), who as a child travelled the world with her father and appears in the film as the young page; two more with actor and Welles biographer Simon Callow (31:41) and critic/biographer Joseph McBride (26:44), who both tackle the difficult circumstances in which Welles worked for much of his career and counter the tiresome received wisdom that he was a “failed Hollywood director” – McBride rightly points out that Welles was an independent artist who happened to work within the Hollywood system a couple of times in his life, while most of his work consists of experiments, some of which were never completed, but all of which explored the possibilities of cinema in great depth. (Throughout his commentary, Naremore repeatedly calls attention to Welles’ art, the richness and subtlety of his work with image and sound.) Finally, there’s a brief interview with Welles himself in the editing room as he was completing work on Chimes, broadcast on the Merv Griffin Show in 1965 (11:07).

Criterion’s Chimes at Midnight Blu-ray is destined to be one of the top disks of the year, finally making this masterpiece available in a form which leaves no doubt about Welles’ brilliance as writer, director and actor, here doing the finest work of his career in all those roles. Viewing Chimes alongside Criterion’s simultaneous release of The Immortal Story, the production which followed it, it’s fully apparent that in the mid-’60s Welles was at the height of his creative powers.

*

Robert Altman, although he too did not fit the Hollywood mold of a studio team player, had better luck than Welles, creating a far larger body of work, often with big-studio backing despite a refusal to adhere to the stylistic norms of the industry. Perhaps if Welles had begun his career a couple of decades later, he would have found a more fertile environment for the kinds of things he was trying to do. With the industry in flux during the late ’60s and ’70s, there was far more space available for experimentation and Altman took full advantage of the opportunities available to him.

Altman’s biggest innovation was an aggressive assault on traditional narrative technique; in much of his work, there is a diffuse quality, a sprawling network of characters and narrative threads within which the viewer is required to navigate. The effect is a kind of simulacrum of actual life, a chaotic stew of events from which the observer must extract a sense of order, in effect constructing a story from the available material. Initially, Altman’s use of crowded frames and a cacophony of overlapping dialogue confused the studios, but as some of his films became hits, and audiences grew accustomed to the technique, his innovations gradually became absorbed into the general palette of devices available to mainstream filmmakers.

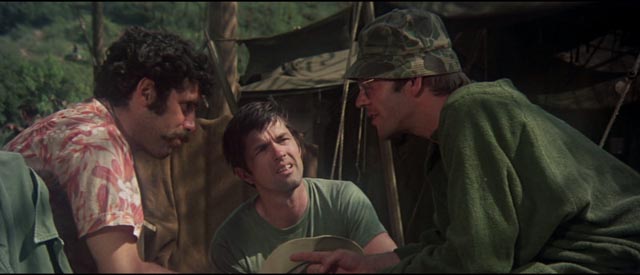

After a couple of small features (which in turn followed years of television work), Altman struck gold with M*A*S*H (1970), a chaotic, bloody and foul-mouthed comedy set ostensibly during the Korean War, but obviously intended to be read as a commentary on Vietnam. The decentred narrative approach also accommodated continual radical shifts in tone, from almost slapstick comedy and verbal play to brutal satire and moments of grim drama. This was the film which established one of the chief characteristics of Altman’s work – a sense of improvisatory invention within a large ensemble cast. Although here and in other movies certain characters do emerge as lead protagonists (while in yet other movies, there is a balance among multiple characters none of whom are privileged above others), there is a sense of a larger and more varied narrative world within which those characters function; this world doesn’t exist to serve their story, rather their story is simply one of many possibilities which the filmmaker might have chosen to focus on.

This technique reached its apotheosis in Nashville (1975), Altman’s attempt to take the national pulse in the wake of Vietnam, with the country reeling from the political fallout of Watergate and the disillusion which had settled in after the social upheavals of the ’60s had failed to forge a newer and better society. As the film’s trailer repeatedly asserts, Nashville features twenty-four characters involved in multiple, intersecting storylines which revolve around the transformation of politics into entertainment. While it was provided a solid framework by writer Joan Tewkesberry, much of the detail was invented on set by Altman and his cast (with the actors even writing their own songs).

In re-watching both M*A*S*H (20th Century Fox Blu-ray) and Nashville (Criterion Blu-ray) recently, I was reminded that neither of them are particular favourites for me – I much prefer McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973), which I consider the director’s two masterpieces – although the sheer energy of both productions is impressive. Altman had an ability to create dense narrative worlds almost unmatched by any of his peers. But he also had a cynical streak which could produce an unpleasant sourness, which for me makes both M*A*S*H and Nashville frequently grating; M*A*S*H has a smug arrogance, embodied in the characters of Hawkeye and Trapper John, a conviction that their (anachronistic) counterculture iconoclasm justifies a cruelty which is objectively just as unpleasant as Frank Burns’ hypocrisy. And yet in the film’s view, that hypocrisy – rooted as it is in religious belief – is unacceptable while the righteousness of the two anti-authoritarian surgeons goes unquestioned.

While this note of moral blindness bothers me in M*A*S*H, what turns me off in Nashville is the sheer noisy busy-ness of the film, particularly exhausting in the first half-hour or so, and the fact that so much energy has been expended on people the director seems to dislike. The film’s view of America is jaundiced and Altman seems to blame all these characters for the sorry state of affairs. I’ve always found it odd that some people interpret the final moments as some kind of affirmation – with Barbara Harris’ Albuquerque getting her moment in the limelight as she takes the stage after the assassination attempt to calm the crowd with the song “It Don’t Worry Me”. Sure, the character at least briefly fulfills her dream, but the sentiment of the song is a resounding disavowal of the previous decade’s atmosphere of political engagement. It represents a turning inward, and seems to foreshadow the rampant egotism that took over society in the ’80s and in a sense validates the cynicism which permeates the film as a whole.

*

While I’m talking about the ’60s and ’70s, I should mention J.G. Ballard as I’ve recently watched Ben Wheatley’s adaptation of his 1975 novel High-Rise. I first encountered Ballard’s work in the mid-to-late-’60s, when I was reading a lot of science fiction. I was particularly drawn to his early catastrophe novels – The Drowned World, The Crystal World, The Drought, The Wind From Nowhere – as I was already a huge fan of John Wyndham’s work. But Ballard’s books were very different from those of Wyndham and John Christopher. Where the typical British apocalypse tended to adhere to a kind of realism in its depiction of people surviving the collapse of society, in Ballard there was something like what would come to be called magic realism, an abstract quality infused with strange and vivid imagery conveyed through prose often so dense and elliptical that it bordered on poetry.

This fabulist quality began to disappear with the publication of The Atrocity Exhibition in 1970 and the novels that followed over the next few years. Here Ballard turned a chillingly clinical eye to human social and political behaviour and the intersection of inner and outer states, largely stripped of conventional psychological and emotional effects; he was like a scientist (not surprising given his initial training as a doctor, which he abandoned to become a professional writer) observing human behaviour through a microscope and jotting down highly condensed observational notes. To be honest, I found the work of this period pretty difficult to get through. Although he was describing disturbing things, it was impossible to feel any emotional engagement.

It has always seemed apparent to me that David Cronenberg had a strong affinity for Ballard’s work, particularly in his earlier films – Stereo and Crimes of the Future are very much like Ballard stories, suffused with that sense of clinical distance and a disturbing interest in perverse psychological and sexual states, while Shivers, coming the same year as the publication of High-Rise, could almost be a pulp gloss on that novel. Cronenberg eventually got around to tackling Ballard directly in 1996 when he adapted the 1973 novel Crash. (Critical opinion is very divided on the film, but I consider it one of Cronenberg’s finest; as an adaptation, it is perhaps inevitably more Cronenberg than Ballard, yet it throws into clear relief just how much influence the writer’s work has had on much of Cronenberg’s career.)

Ben Wheatley and his writing partner Amy Jump were faced, just like Cronenberg, with the particular difficulty of translating Ballard’s dense prose into visual and dramatic terms. The novels have little of what we would conventionally call character and narrative incident and so a filmmaker has to invent a great deal, devising a dramatic structure which can support Ballard’s chilly observations; this process in itself risks destroying the essence of the original because the moment psychology and emotion are introduced, the movie becomes un-Ballardian. (Steven Spielberg had an easier job of it with his adaptation of Ballard’s autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun, because that work was all about the psychological and emotional states of the boy Jim as he navigates the monstrous world of the Japanese prison camp in Shanghai during World War Two.)

Ballard’s High-Rise was rooted in the post-war warehousing of the working class in brutalist tower blocks in major English cities, the social and psychological consequences of which had become apparent and been widely studied during the ’60s. (An episode of Doomwatch dealt with this in 1971, depicting these towers as a cause of deep psychological disturbance.) Ballard layered on a chilling critique of class warfare, with the tower deliberately stratified with privilege at the top and increasing oppression towards the lower floors. (It’s easy to believe that Ballard influenced the graphic novel Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette, which was adapted as Snowpiercer by Joon Bong-ho in 2013; there are many structural similarities between the two works.)

Inevitably the act of adaptation alters the work to some degree. Wheatley’s High-Rise is colourful and visually dynamic, and this tends to work against the clinical starkness of the book. The film builds on the satirical aspects of the text, producing a more comic edge. Perhaps the most significant creative choice was Wheatley and Jump’s decision to set the story in a kind of alternate ’70s as if they had made the film at the time of the book’s publication; this is not some futuristic fantasy, but rather a critique of the social upheavals which produced the destructive monstrosity of Thatcherism. To emphasize the point, the film ends with the sound of Margaret Thatcher’s voice delivering a speech promising a glorious future, heard in the wake of the complete and violent collapse of society.

It isn’t surprising that there have been few adaptations of Ballard’s work given his distinctive style and frequently difficult and transgressive content. Probably the most faithful feature is also the least commercial – Jonathan Weiss’ The Atrocity Exhibition (2001), a film which not only manages to find a cinematic analogue for the author’s highly compressed stories in that groundbreaking “anti-novel”, but also evokes the strong connections between Ballard’s writing and those early Cronenberg films. As in Stereo and Crimes of the Future, The Atrocity Exhibition comes in the form of a clinical report about illicit psychological experiments. Fascinated by mankind’s penchant for violence and perversity, researcher Travis Talbert embarks on a program which recreates various historical atrocities. Weiss combines scenes in the sterile institution with a richly varied assemblage of documentary footage, most prominently images from Hiroshima, the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination, and military footage from the Vietnam war.

The film has the dense yet detached tone of the book, as if human activity were being observed by dispassionate aliens who are struggling to understand the appallingly destructive, and self-destructive, behaviour of our species. More than the other adaptations, The Atrocity Exhibition illustrates both the advantages and limitations of close adherence to the original text; still little seen, it is unlikely ever to break out of a rather small niche. As far as I know, it has only ever been available in a limited edition from a Dutch company named Filmfreak, which actually started a DVD line (Reel23) specifically to release it. That edition, very nicely produced, with no less than two commentary tracks (one with Weiss solo, the other with the director in conversation with Ballard, who seems to admire the film), can still be found at highly inflated prices on-line. (There was a fascinating, lengthy and very prickly interview with Weiss about the film on a site called Ballardian.com, which has now been shut down – the interview can still be found on the WayBack Machine here; it’s a good illustration of the risks involved when an artist decides to take personal offence at criticism of his work.)

Comments