Leonard Cohen, Robert Altman and an elegy to a national myth

The news last week that Leonard Cohen had died was sad but not unexpected; his health had been in decline for some time. Yet it was only four years ago that he was on his monumental world tour. I was lucky enough to get a ticket to his sold-out show here in Winnipeg and it was not simply the best concert I’d ever been to – it was, quite literally, almost a mystical experience. During the uninterrupted, almost three-hour performance the 78-year-old poet-singer became more and more energized as if he were channelling some force and projecting it out into the audience. He had amazing grace and authority on stage and showed deference and respect to all the musicians performing with him.

I’m really glad I had that opportunity to see him live, because until then I was only what you might call a “casual fan”. I had all his albums on vinyl back when I had a collection of LPs, but he was just one among many (Brian Eno, Lou Reed, John Cale …) who I listened to regularly. I’ve never read his poetry or fiction, so for me he’s always been a singer, a wry and melancholy chronicler of the underside of romance. No doubt I had heard his first hit, “Suzanne”, many times on the radio in the late ’60s, but I really only became conscious of him in 1971 when that distinctive voice established a very particular mood over the opening moments of Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Although Cohen’s songs may not be “period appropriate” to the film, they were absolutely essential to the tonal and emotional qualities of what remains Altman’s greatest work.

A strange coincidence then that this masterpiece should finally get a worthy release on disk just a few weeks before Cohen’s death.

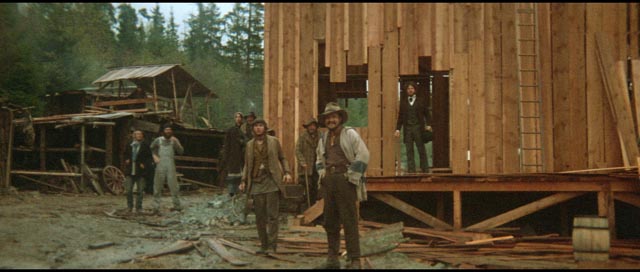

The opening shots of the film, with McCabe’s slow ride up a mountain trail in the rain, finally reaching the still unfinished town of Presbyterian Church, create a mood which can only be described as something like hopeful melancholy. McCabe has come here determined to establish a business among the rough male population of miners and those who supply and exploit them. A gambler (and dubiously reputed gunfighter), he plans to build a saloon and gambling house, with a brothel as a side line. He has charm and ambition, but as we gradually learn is not particularly smart. He’s rather naive in his faith in the possibility of remaking himself on the frontier.

Success only really arrives when he is joined by Mrs. Miller, a woman with energy and practical skills and a fine understanding of the business of prostitution; she knows how to manage and take care of the women who work for her and, more importantly, how to manage the customers. Installing herself as McCabe’s business partner, getting him to build a bathhouse which the men are required to use before visiting the brothel, she miraculously introduces a degree of civilization to this rough-hewn community and along with it a new self-respect among the men who make use of the services she provides.

This is perhaps the most striking narrative element in the film. As he would so often do, Altman here takes familiar genre elements and deconstructs them in order to piece them together again in ways which transform and illuminate what has become too familiar. The stranger who rides into town to take charge; the whores who serve the men’s needs … these are standard tropes of the western. But here, the man is ineffectual and the woman takes charge. Civilization is carved out of the wilderness not with the gun and masculine authority, but rather by a woman who understands the finer points of business. It’s small-scale commerce which tames the West.

But this being the raw foundations of capitalism, things are not likely to remain stable and before long representatives of a powerful mining company arrive in town to buy everything up, including McCabe’s business interests. (It’s telling that he’s the one they try to make a deal with, not his more astute female partner.) Being a little naive, a little dumb, McCabe fumbles his attempt to negotiate and the impatient mining company representatives can’t be bothered to stick around and dicker; there are quicker and simpler ways to get what they want and soon three gunmen arrive to remove the obstacle.

All this may sound quite straightforward, but Altman and his collaborators were not simply deconstructing the genre; they were aggressively deconstructing the traditional way of making a commercial movie at the same time. Although he was coming off the commercial flop of Brewster McCloud (1970), Altman – as he did through much of his career – was working quickly on this new project and the success of M*A*S*H was enough to carry him here despite the misgivings of the studio people who considered him reckless.

First there were radical technical decisions: he had cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond pre-flash the film stock, a technique which was not entirely controllable and ran the risk of ruining the footage being shot on location. It involves exposing the film to a flat white light in the lab, so that subsequent exposures produce a softer, less contrasty image with a degree of colour desaturation. (Altman and Zsigmond used the same technique in their next two films, Images [1972] and The Long Goodbye [1973].) The resulting image shows increased grain and a warmer, softer look which, in this instance, produced what Altman hoped would be the impression of an older, faded film, one which might somehow have been shot on location back at the time the story takes place.

On top of this, Altman pushed the overlapping dialogue which had been used to a lesser degree on M*A*S*H. Here, every actor was individually mic-ed, recorded to his or her own discrete channel so that the director could play with all the voices in the mix as if they were separate instruments in a musical composition. This seriously concerned the studio people and enraged a lot of reviewers at the time – you couldn’t hear all the dialogue! Instead, you catch fragments, a word here, a phrase there, all these notes building up an impression of meaning which it’s up to the viewer to piece together. This is a film which doesn’t spell things out, but rather asks the viewer to interpret meanings from the flow of sounds and images.

While the overt effect is to give the film a decentred feel, more subtly it fills it with a sense of life; the entire community vibrates with energy, every character no matter how briefly glimpsed adding to the richness. For all its humour, its satirical edge, McCabe & Mrs. Miller projects an air of authenticity unlike any other western; rather than the long-standing myths of the frontier, we feel that this must be what life was actually like at this time, in this specific place.

This communal aspect of the film was apparently of some concern to star Warren Beatty, who was not exactly used to Altman’s improvisatory methods and the spreading of screen attention across such a large ensemble. And yet, Beatty gives here one of his finest performances – as does Julie Christie as Mrs. Miller. In fact Beatty works against his star’s authority, giving the character a sweetness and vulnerability which is crucial to the romantic thread which is gradually woven through the broad narrative fabric. His obvious attraction to Mrs. Miller gives rise to poignant, tentative gestures which emphasize the almost childlike (at least adolescent) core of the man. The rugged western hero is exposed as an immature romantic construct, his immaturity provoking the final eruption of violence – not the heroic, cathartic violence we’ve come to expect from the genre, but something brutish and pointless, a round of ambush and back-shooting and, in its final moment, the use of an underhanded “coward’s” concealed weapon. There is no glory here, just pointless extinction, and that famous final image of Mrs. Miller in an opium haze speaks to her quiet despair over the stupidity of men who aren’t capable of seeing what’s important … a despair we now understand as the cause of her reluctance to commit fully to a relationship with McCabe.

Beyond the two radical technical aspects of the film, Altman also took a highly unusual approach to the shooting. The film’s large outdoor set was being constructed throughout production, with the crew dressed in period costumes so that they could keep working in the background as scenes were shot. We see the town gradually taking shape on screen in parallel with the drama of the narrative; these raw wooden structures were practical buildings, allowing Altman and Zsigmond to shoot inside as well, again while they were under construction. This too gives the film a remarkable sense of authenticity, a genuine documentary element which supports the narrative.

Altman’s desire to improvise and catch things as they happened was also responsible for the remarkable final sequence, the protracted shoot-out during a snowstorm. No one had expected the snow, and when it did fall over a weekend towards the end of the shoot, he was told it would all be gone in a couple of days. But he took a risk and shot the entire sequence at high speed; this was production value money simply couldn’t buy. There are some shots where falling snow has been added optically in an attempt to match the real thing in surrounding shots, and sometimes this is not entirely successful – but given what he gained from nature here, these few little artificial fixes are a minor distraction.

There are so many details in this richly conceived film that one could go on cataloguing them endlessly – the characters who come and go, small but telling comic moments, the abrupt shift in tone quite late when the reality of violence suddenly overshadows everything else. It’s a film steeped in its period, in nuances of behaviour and emotion, visually exquisite, with a huge cast in which even the smallest role is privileged. And the whole wonderful edifice is ultimately held together by those Leonard Cohen songs – songs which predated the movie, yet seem perfectly apt, not so much in the lyrics which seem to comment on events as in their tone. Through them, McCabe & Mrs. Miller becomes an elegiac ballad, a rueful reverie on the failure of a great national myth. As richly as it was produced, it’s impossible to imagine the film without Cohen’s voice.

It was after seeing the film for the first time (several times in fact) in 1971, that I became a lifelong Cohen fan. He’ll be missed.

*

McCabe & Mrs. Miller, because of the photographic technique, is a notoriously difficult film to transfer to video. Previous home video versions – on VHS and DVD – looked awful, the soft, grainy textures turning to mush. Criterion have taken great care with their Blu-ray, the 4K transfer capturing the delicate nuances of Zsigmond’s photography, colours having an almost pastel quality.

The mono sound is a bit problematic, as it always has been; there’s a slightly muffled, hollow quality to much of the dialogue which is no doubt due to the equipment used for all that individual mic-ing. Although occasionally distracting, it’s not enough to undermine the viewing experience.

The disk is packed with almost three hours of supplements, in addition to the commentary track Altman recorded with producer David Foster for the old Warner DVD. The 55-minute retrospective making-of is an excellent overview of what made the production so unique; a somewhat rambling conversation between film historians Cari Beauchamp and Rick Jewell relates the film to the western genre and its connections with and differences from the Edmund Naughton novel it was based on; there’s a post-screening Q&A from 1999 focusing on the work of production designer Leon Ericksen; interview clips with Zsigmond in which he talks about the pre-flashing technique and working with Altman; and two segments from the Dick Cavett show, the first with Pauline Kael defending the film against what she views as ignorant criticism from mainstream reviewers, the second with Altman himself talking about the film. The original trailer shows a publicity department unsure of how to sell such an unusual film.

The booklet essay is by critic Nathaniel Rich.

Comments

My favorite Altman as well.

As you so well express, I remember being amazed how appropriate Cohen’s music was, as if it must have been written expressly for the movie, though I knew it was predated.

A reflection of Altman’s genius, I suppose.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller is one of my top five favorite films and certainly my favorite film by Altman. A book exists about this film by Theodore T. Self (Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs.Miller, Reframing the American West published by University of Kansas Press in 2007. Naughton’s book (McCabe) is worth the read. The ending is predictable but it looks like Sheehan will get his just desserts, courtesy of Mrs. Miller.

I first became aware of Leonard Cohen through Judy Collins and her singing of “Hey that’s no way to say goodbye” on her Wildflowers album. I became a permanent Cohen fan after actually listening and parsing the lyrics of “Famous Blue Raincoat.” I saw him three times (2008-2012). Godwin’s description of the concerts as mystical is apt. I have listed Leonard Cohen as my religion for decades. Altman called Cohen and asked if he could use his songs for an upcoming film. Cohen had never heard of Altman and told him so. He asked him films he directed. Altman told him “Mash.” Cohen had never heard of it. Cohen asked, what else and Altman responded “Brewster McCloud.” Cohen said he had recently seen that movie and loved it. Sat through the next showing. He told Altman he could use any of his songs, so we got “The Stranger Song” for McCabe, “Winter Lady” for Mrs.Miller, and “Sisters of Mercy” got the prostitutes. That song was the one song of Leonard’s that was written in one night and was based on two young women that he invited to stay in his room overlooking the Saskatchewan River in Edmonton, Alberta in a snowstorm. The women were getting shelter in the vestal of the hotel when Leonard returned from a public performance.