Recent disks from England, part two

The Land of Hope (2012)

I became interested in the films of Sono Sion the moment I saw the audacious opening scene of Suicide Circle more than ten years ago. Although Sono isn’t as prolific as Takashi Miike, his work is often as transgressive and stylistically exciting (IMDB lists 39 directing credits for Sono against 93 for Miike, although Sono’s first is dated six years before Miike’s). Both directors possess a wildly imaginative approach to film which allows them to shoot off in strange and unexpected directions, which for a western viewer provides refreshingly unpredictable viewing experiences. And as with Miike, Sono’s films are sometimes a bit uneven in execution. The shot-in-New York Hazard (2005) was a disappointment, while Exte: Hair Extensions (2007) was a fairly conventional Japanese long-haired-ghost story. Strange Circus (2005) is an hallucinatory, multi-layered fantasia centred on a woman who was abused as a child, while Noriko’s Dinner Table (made the same year and nominally a “sequel” to Suicide Circle) is an epic meditation on the disintegration of the Japanese family in a morally bankrupt society. The theme of the fragility of identity in a culture which is no longer coherent runs through most of Sono’s best work, including his epic masterpiece Love Exposure (2008) and the post-tsunami melodrama Himizu (2011).

It’s also present in the more recent The Land of Hope (2012), released in England on Blu-ray by Third Window Films, accompanied by a 70-minute, somewhat impressionistic documentary about the production.

On its surface seemingly calmer than much of Sono’s work, The Land of Hope resonates more deeply with a sense of stoicism warding off despair. Inspired by the Fukushima reactor disaster, the film recounts the story of two families whose lives are irrevocably changed when a nuclear plant blows and the authorities create a safety perimeter which literally runs down the street between their two houses. On one side, people are bused off as refugees, while on the other an elderly couple stay in the farm house where they’ve lived their entire lives. (This situation is rooted in reality, as the documentary shows; Sono was inspired in his research when he found a family whose garden was split in two by the exclusion boundary. They were free to stay in their house, but forbidden to cross into the other side of the garden, as if radiation contamination had been contained by the flimsy fence.)

Yasuhiko (Isao Natsuyagi) and his wife Chieko (Naoko Otani) see no reason to abandon the world they’ve known all their lives, particularly as Chieko is slipping into dementia and needs the anchor of familiar surroundings; but Yasuhiko insists that his reluctant son Yoichi (Jun Murakami) take his wife Izumi (Megumi Kagurazaka) far from the danger. Outside the disaster area, Yoichi and Izumi meet with prejudice and suspicion from people who would rather not think about radioactive contamination. When Izumi becomes pregnant, she becomes consumed with paranoia about the safety of her baby, sealing up their small apartment and buying a full-body radiation suit which she wears outside, drawing ridicule and resentment from their neighbours. And so the film quietly follows these lives shattered by an event over which they had no control and about which the authorities continually lie. Yet Sono manages to find some hope in the mere fact of survival, the possibility of carrying on despite such catastrophic change. In The Land of Hope, he goes beyond the brutal shocks which characterize much of his work to find something deeper and more moving, while continuing his acerbic critique of contemporary Japan.

*

Violent Saturday (1955)

Eureka’s dual-format edition of Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955) is a quantum leap beyond Twilight Time’s disappointing DVD from 2011 (that was a standard definition, non-anamorphic transfer, apparently made years ago for a laserdisk release. The Blu-ray is really striking, with a lot of depth and detail in the 2.55:1 image. The film itself, scripted by the versatile Sydney Boehm from a novel by William L. Heath, is a fascinating hybrid – a noirish crime story dealing with three men who arrive in a small desert town to rob the bank mixed with a multi-character narrative about various citizens whose lives gradually converge at the time of the Saturday afternoon heist. Fleischer manages to balance all the elements effectively, allowing each character to acquire some depth – all are flawed, morally compromised, the explosion of violence forcing resolutions for many of them of deep-rooted problems.

While there are touches of absurdity – the action climax which takes place on a small Amish farm where the pacifist father is finally pushed to (what for him is) an unforgivable act of violence in order to save another man’s life – much of the film has the air of eavesdropping on the small sins of ordinary people. Sylvia Sidney as the heir of the town’s founder, now fallen on hard times and working as a librarian, who commits a petty theft in order to save herself from harassment by the local banker; Tommy Noonan as the bank manager who has developed a voyeuristic fixation on company nurse Virginia Leith. Richard Egan, the alcoholic partner in the local mining company, driven to despair by his love for unfaithful wife Margaret Hayes; and Victor Mature as Egan’s partner, a man whose son is ashamed because he didn’t go to war and become a hero like his classmates’ dads.

Weaving in and out of these lives, the three-man gang methodically plan their job, timing everything to the second while increasingly rubbing each other the wrong way. Stephen McNally is in charge, with J. Carroll Naish and Lee Marvin along to do the work. Marvin is terrific as a coldly vicious thug addicted to nasal spray. In fact, the entire cast is excellent. If the film lacks the tension of Asphalt Jungle and The Killing, it’s not because of any shortcomings on the underrated Fleischer’s part; his approach is leisurely, allowing the various elements to coalesce with quiet inevitability around the robbery, when violence shatters all the petty tensions which have been steadily accumulating.

Fleischer was a skillful director who always served his material rather than imposing himself on it. If we get no clear sense of his personality from his broad body of work, many individual films do stand out, beginning with Armored Car Robbery (1950), The Narrow Margin (1952), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) on through Compulsion (1959), The Boston Strangler (1968) and 10 Rillington Place (1971). He was capable of handling big studio productions like The Vikings (1958) and (less successfully) Doctor Dolittle (1967), and despite its reputation, Mandingo (1975) is a far more incisive portrait of the perversity of the slave-owning South than Tarantino’s obnoxiously smart-ass Django Unchained. Although he kept working into his 70s, his later work is less interesting, sadly petering out at last with Dino De Laurentiis’s Million Dollar Mystery (1987). So it’s nice to see this unusual film from the mid-’50s given new life on disk. Adding to the value of Eureka’s release is the inclusion of an enthusiastic 21-minute appreciation of Fleischer by William Friedkin and a 28-minute visual essay about the film by French critic and filmmaker Nicolas Saada, plus a lengthy booklet with an essay by Adam Batty and a reproduction of the original Exhibitor’s Campaign Book.

*

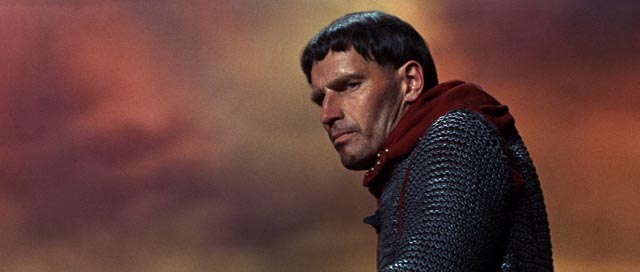

The War Lord (1965)

Eureka’s Blu-ray release of Franklin J. Schaffner’s medieval romance The War Lord (1965) is also a big improvement on earlier DVD editions (in region 1 from Good Times Video and region 2 from Eureka). Schaffner is best known, of course, for Planet of the Apes (1968) and Patton and a few other big movies from the ’70s, which seemed to get progressively duller (Nicholas and Alexandra, Papillon, Islands in the Stream, The Boys From Brazil). He got his start in live television during the ’50s (including the original Twelve Angry Men [1954] for Studio One), making the transition to theatrical features with The Stripper (1963) starring Joanne Woodward and Gore Vidal’s The Best Man (1964) starring Henry Fonda. But then the next year, following those small personal dramas, he made the surprising decision to adapt The Lovers, an unsuccessful play by Leslie Stevens (creator of The Outer Limits). I’ve been a fan of this intimate historical epic since I first saw it on TV (pan-and-scanned in black-and-white) back in the early ’70s, and now the Blu-ray finally does it justice on home video.

Although Schaffner’s budget didn’t stretch to shooting on location in Europe (he filmed in California), The War Lord nevertheless feels more authentic than most Hollywood historical epics. The biggest issue for a viewer is getting past the very American cast which initially creates an odd tonal discordance, despite the excellent, detailed production design. But once you accept Charlton Heston, Richard Boone and Guy Stockwell as medieval Frenchmen, the movie seldom falters. Heston as the knight Chrysagon is more or less able to suppress his resentment for the loss of his family heritage (the result of everything having to go to pay ransom for his father, kidnapped by northern barbarians), relegated now to serving another lord and assigned to guard a remote bit of land on the borders where the local peasants pay only lip service to Christianity, while still adhering to their ancient pagan rites. Chrysagon is aided by his faithful lieutenant Bors (Boone) and his bitter younger brother Draco (Stockwell). Lonely and depressed, Chrysagon becomes attracted to a local woman, Bronwyn (Rosemary Forsyth), and unable to get past the “spell” he feels she’s cast on him, on her wedding day he claims the right of the lord to be the first to possess the virgin bride. This triggers the seething resentment of the peasants, who ally themselves with the barbarians to lay siege to the small castle.

The movie, scripted by John Collier and Millard Kaufman, does a fine job of playing the story’s various forces against each other, and Schaffner skillfully balances the spectacle (the protracted siege of the castle is a fine piece of sustained action filmmaking) with the personal, emotional elements. Often when Hollywood took on this kind of historical subject, the results leaned far more towards the spectacle (even in such well-made movies as Anthony Mann’s El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire), with characters all but buried under the weight of the production. The War Lord manages to keep its human drama in focus at all times, using personal feelings and motivations to drive the larger-scale action. Although largely forgotten in the wake of Heston and Schaffner’s follow-up collaboration, Planet of the Apes (1968), The War Lord stands as one of the finest pieces of work done by both actor and director, deserving to be raised in both audience and critical estimation – a process which this new Blu-ray may help to initiate. Although not surprising given the film’s age (almost 50!), it’s a pity Eureka offers no supplements, only providing a booklet featuring a new essay by Michael Brooke, Tom Milne’s original favourable review from Monthly Film Bulletin, and excerpts from Heston’s diaries kept during the long process of development and production.

*

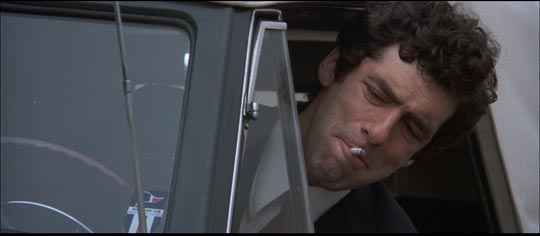

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Robert Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s final major Philip Marlowe novel (it was followed by the minor Playback and the unfinished Poodle Springs) was not well-received when it was first released in 1973. Chandler purists disliked what Altman and scriptwriter Leigh Brackett (who previously had scripted Howard Hawks’ classic The Big Sleep from an earlier Chandler novel) had done with the character. And yet, in retrospect, despite the liberties taken, The Long Goodbye can be seen as one of the peaks of Altman’s fascinating early career in features (after years of television work in the ’50s and ’60s).

In contrast to Robert Towne and Roman Polanski, whose Chinatown was released the following year, Altman had no interest in doing a period film which would risk being mere pastiche. Instead, he relocated the character of detective Philip Marlowe to contemporary southern California as if he had somehow slept through the previous twenty years. Elliot Gould has Marlowe almost sleepwalking through a world of moral compromise, betrayal, lost ideals; this disconnection infuriated people who prefer their detectives proactive and in charge of circumstances. It’s quite true that Gould’s Marlowe does very little detecting; he drifts on a tide of contingency, but nonetheless finds himself constantly at the centre of events, a witness to lives crippled by a lack of purpose combined with monumental egotism. The film is a wry portrait of America at the end of the Nixon era, a time when it was all too easy to throw up one’s hands in disgust and walk away from the corruption. Marlowe, however, is morally affronted by what he learns and (again to the horror of the purists) puts an end to the friend who used and betrayed him in a final act which still has the power to shock.

Like so many of Altman’s best films, The Long Goodbye has a terrific – and somewhat unconventional – cast. The film gave Sterling Hayden one of his finest roles as the tortured alcoholic writer Roger Wade, which drew deeply on the actor’s own history (having testified and named names to the House Un-American Activities Committee in the ’50s, Hayden was haunted by that act for the rest of his life). As Wade’s wife, Altman cast Danish former folk singer Nina van Pallandt, at the time famous for her relationship with hoax Howard Hughes biographer Clifford Irving; that same year, she appeared in Orson Welles’ brilliant, playful F For Fake. The film marked the first of four appearances for Altman by comedian Henry Gibson, a small man who rather frighteningly intimidates the much bigger Hayden as a creepy fake psychologist who’s blackmailing the writer. Director Mark Rydell appeared as vicious gangster Marty Augustine, while baseball player Jim Bouton gives a breezy, cheerful performance as Terry Lennox, the friend who betrays Marlowe. And, surprising in retrospect, none other than Arnold Schwarzenegger turns up in a funny, non-speaking cameo as one of Augustine’s henchmen.

Coming after the rather brittle stylistic experiment of Images (a film which holds up less well now), The Long Goodbye stands with McCabe & Mrs Miller as the greatest of Altman’s ’70s films; both works with a loose, improvisatory feel which nonetheless maintain a rigorous narrative control with an almost tragic view of characters lost in a world defined by economic transactions. At base, these are depictions of what capitalism does to people’s lives and personalities.

Arrow’s Blu-ray does a superb job with this underrated film, managing to capture the distinctive look created by Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond by pushing to extremes the technique of flashing they’d previously used on McCabe. This involved exposing the undeveloped negative to varying intensities of light which affected colour depth and contrast levels; the result is a soft, almost pastel image with a high degree of picture detail – tricky to transfer faithfully to video. (There’s a fascinating article in the accompanying booklet reprinted from American Cinematographer, which goes into a lot of detail about the risks and benefits of the process, as well as a 15-minute interview with Zsigmond on the disk.)

As is now often the case with Arrow, the disk is packed with contextual supplements, including a 53-minute Q&A with Gould in which he discusses the film and his debt to Altman for more or less saving the actor’s career by giving him the part; a 24-minute piece called RIP Van Marlowe, in which actor and director talk about their approach to the character; a 56-minute documentary about Altman and his career; a 21-minute interview with critic David Thompson about the film; the aforementioned interview with Zsigmond; and two 15-minute interviews about Chandler and hard-boiled fiction in general.

Comments