More in-flight entertainment

Flying to England a few weeks ago for my nephew’s wedding, my experience of airline entertainment was even less satisfying than on my trip to Beijing last year. As before, the wide selection of movie choices was undeniably eclectic – in the “avant garde” section, for instance, we were offered Morgan Spurlock’s Comic Con Episode IV, Will Ferrell’s Casa de mi padre and Terence Davies’ Deep Blue Sea. (I’d be interested to know what dictionary definition some airline employee was using to create that category!) But the seat-back touch-screen was glitchy and program playback erratic. I just hoped that mechanical maintenance on the plane was more reliable than maintenance on the individualized entertainment system …

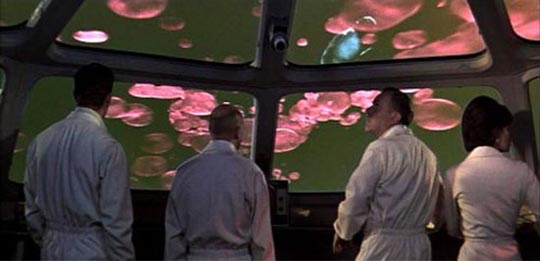

In classics, there were the usual Chaplin shorts, Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men, Citizen Kane … on the flight out, I opted for Richard Fleischer’s Fantastic Voyage (1966), inevitably pan-and-scanned, but less likely to suffer from the noisy, small-screen situation than something more demanding (no way was I going to attempt Davies’ film in that environment). For all its blatant nonsense elements, Fantastic Voyage still holds up as an enjoyable pulp entertainment. I’m surprised no one has tackled a CG-driven remake as the basic idea certainly offers interesting dramatic and visual possibilities (of course, Joe Dante leaned on the absurdist elements of the story in Innerspace [1987]).

If you can accept the basic premise – a submarine and its medical crew are miniaturized to microbe-size in order to get at a fatal blood clot deep inside the brain of a scientist who possesses a vital Cold War secret (related to the miniaturization process) – the story is quite engaging. Despite the assertion that the movie had scientific and medical advisers, and that the design is colourful in a comic book kind of way, the interior of the body is not very convincing – spacious and far too brightly lit (where does all that light come from?). The plot is basic Cold War espionage adventure, with an enemy agent aboard trying to sabotage things … and the casting is too obvious to offer any real surprises: could the bad guy be Raquel Welch (who looks good in a wet suit)? Or is it stern surgeon Arthur Kennedy? Or could it possibly be Donald Pleasance in full nervous weasel mode?

According to Isaac Asimov, who wrote the novelization of the screenplay, the biggest technical error in the whole story lies in what would happen to a laser if miniaturized to the degree of the one in the movie; it would no longer emit a blood-clot-disintegrating laser beam, but rather some other kind of less useful microwave radiation. But plot-wise, the biggest error is the idea that the white blood cells enveloping the submarine (with the enemy agent still inside) would neutralize its reversion to full size when time runs out. The surviving crew members make it to a tear duct just in time, but given the story’s premise, wouldn’t the scientist’s head explode as the vessel expanded?

Unwilling to squint my way through a subtitled foreign movie, I passed on Agnieska Holland’s In Darkness, the Iranian A Separation, and the Chinese films White Vengeance, I Love Hong Kong 2012 and Wings of the Kirin, and opted for the Contemporary Hollywood choice Safe House (2012), a slick and generally pointless thriller of the kind that Denzel Washington now seems to do all too often in his sleep.

Shot in South Africa with very little sense of place – it could be anywhere – it has Ryan Reynolds (no one’s idea of an action hero) as a time-marking CIA operative in charge of the titular installation which is kept ready at all times in case the agency needs to torture some hapless captive. In this case, it’s a rogue agent named Tobin Frost (Washington) who has supposedly been selling secrets to enemy governments. As he’s being water-boarded, the house is attacked by armed men and Reynolds is forced to flee with the prisoner while everyone else is killed. The rest is a by-the-numbers chase during which the two men uneasily bond while we learn that there’s corruption deep inside the agency and Frost has the information on who the bad guys are. Admittedly, it might have been more entertaining on a big screen at the proper aspect ratio, but Swedish director Daniel Espinosa brings nothing fresh to the material.

On the return flight, I settled for the familiar comforts of Howard Hawks’ The Thing From Another World (1951). This was the first directing credit for Christian Nyby, who had a distinguished career as an editor going back to 1943, including a number of Hawks’ best films – To have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, Red River, The Big Sky – as well as Fritz Lang’s Cloak and Dagger, and Raoul Walsh’s Pursued, Cheyenne and Fighter Squadron. The belief that The Thing was really directed by Hawks is fairly easy to credit as nothing in Nyby’s subsequent and prolific television career comes close and this, one of the best of the ’50s science fiction movies, is full of Hawksian elements – the tight-knit group of proficient working men, the tough dame who holds her own in their masculine world, and adversity overcome by group effort. Stylistically, the fast-paced, snappy, overlapping dialogue is a key Hawks signature, and there isn’t a wasted moment or gesture in the lean 87-minute running time.

There are people who revere The Thing From Another World and use that respect to denigrate John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), but the comparison is unnecessary. They’re two different animals, so to speak. The 1951 film was one of the earliest and best of that decade’s exercises in the threat-of-the-Other which could be read as a veiled metaphor for fears of communism, an “alien” ideology which seemed poised to overrun democracy and individualism. But the “walking carrot” monster, despite the assertions of Dr. Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite) that it’s obviously vastly superior to us – typically emphasizing its lack of crippling emotions – really is portrayed as a mindless rampaging beast. It’s hard to credit it with the technological superiority necessary for interplanetary travel.

Carpenter’s film, made as the Cold War was approaching its final unstable stages, returned to the concept of John W. Campbell’s original story, Who Goes There? (1948, writing as Don A. Stuart), featuring an alien which can absorb and replicate any living form. Hawks and Nyby’s film presented a physical menace which can be confronted and defeated by military ingenuity; Carpenter’s (well-scripted by Bill Lancaster), like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (in its various incarnations – Jack Finney’s original novel [1955], and the adaptations by Don Siegel [1956], Philip Kaufman [1978] and Abel Ferrera [1993]), is about a different kind of paranoia, the fear of losing one’s personal identity to an all-consuming undifferentiated Other. Carpenter’s choices are partly due to changing social and political factors, but also obviously a result of technological advances which allowed him and his FX crew to go far beyond a man-in-rubber-suit monster.

Both versions work very well on their own terms and there’s no need to choose between them.

Despite feeling exhausted as the flight dragged on, I attempted to watch the Farrelly Brothers’ update of The Three Stooges (2012). I’m not sure I would have stuck it out even if the on-board entertainment system hadn’t started to malfunction. Visually flat, with what seemed like merely a mechanical reiteration of the standard Stooge slapping-and-eye-poking schtick, lacking the energy of the originals and more critically injected with inappropriate sentimentality, it was pretty unengaging – so when it suddenly disappeared into a mess of digital static, I exited the system and tried to sleep.

Comments

Avoid those carrot monsters.