Recent fantasy and horror on disk

Looking over the pile of recently viewed Blu-rays, I’m not surprised to see quite a few fantasy, horror and sci-fi movies, as well as a few more Asian action films and dramas. As I’ve already focused on the latter in my previous post, I’ll make a few comments about the former today.

Villages of the Damned

Villages of the Damned: Three Horrors from Spain is a two-disk set from Vinegar Syndrome featuring three otherwise unrelated movies from the ’70s, two by filmmakers I’m unfamiliar with, the third by a Canadian transplant to England best known for a couple of features from the mid-’60s.

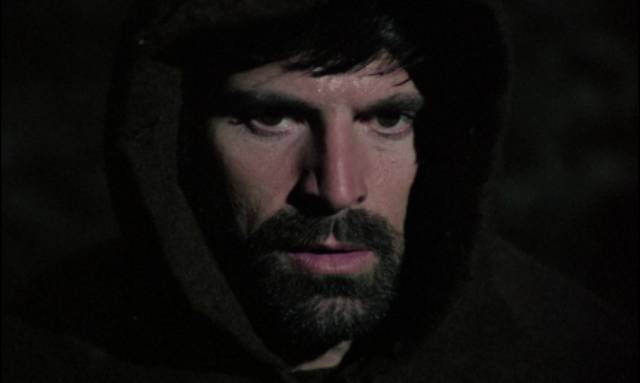

El bosque del lobo (1970) was the second feature of Basque co-writer/director Pedro Olea, adapted from a novel by Carlos Martinez-Barbeito, which in turn was based on the mid-19th Century case of Manuel Blanco Romasanta, a peddler who committed a number of murders as he travelled between the towns and villages of Galicia. His crimes, wrapped in superstition and folklore, gave rise to local legends of a werewolf. Olea’s film roots them in childhood trauma and epilepsy – he kills in the throes of seizures and blackouts, which he himself attributes to a transformation over which he has no control.

With Olea’s focus closely tied to the peddler, renamed Benito Freire, we see events through his eyes, coloured by his own despair, as the various inhabitants of the towns gradually become aware of his crimes and eventually hunt him down like a beast (he’s finally captured when his foot gets caught in an animal trap). There’s no mystery in the story, and the suspense paradoxically arises from our identification with Benito and a fear that he’ll be caught. This empathy is rooted in the performance of José Luis López Vázquez as the peddler, a pathetic, tormented outsider more tolerated that liked by the people he sells his goods to. It’s a remarkable performance which gives the film an air of tragedy.

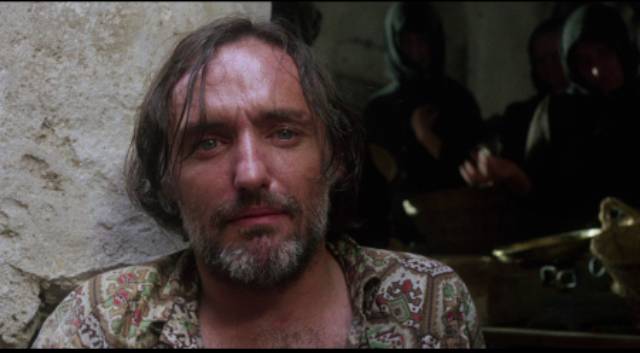

Gonzalo Suárez’s Beatriz (1976) also draws on folk horror for its dreamlike depiction of an adolescent girl’s sexual awakening, which occurs in a context of superstition and violence in a Medieval setting. Partially viewed through the eyes of her younger brother Juan (Oscar Martin), events remain enigmatic and unclear, the motives and behaviour of adults a mystery. In the opening sequence, Juan is walking through woods when he sees a darkly-cowled figure on the path; believing it’s the Devil, he runs and is grabbed by a gang of outlaws who lay an ambush for the stranger. But this stranger, a wandering friar, is armed and cuts down several members of the gang before the rest flee.

The friar, Fray Angel (Jorge Rivero), arrives at Juan’s family home, where he lives with his mother Dona Carlota (Carmen Sevilla), the servant Basilisa (Nadiuska), his sister Beatriz (Sandra Mozarowsky) and the scholar Maximo Bretal (Jose Sacristan). There are undercurrents of sexual tension flowing in multiple directions (including some uncomfortable physical play between Basilisa and Juan) and the presence of Fray Angel stirs things up, with Beatriz seemingly becoming possessed … but from a modern perspective the supernatural intimations suggest psychological phenomena. The aura of superstition intensifies when the remnants of the outlaw gang break in wearing animal masks, terrorizing the family (and brutally raping Basilisa, who becomes a kind of sacrifice to spare Dona Carlota and Beatriz).

The odd one out in this trio of movies is The Sky Is Falling (1975), a painfully ill-conceived contemporary story which I could barely sit through. Directed by Silvio Narizzano, whose Die! Die! My Darling! (1965) was one of Hammer’s best psycho-horrors of the ’60s, while Georgy Girl (1966) was a key movie of London’s Swinging Sixties. After that brief period of success, Narizzano stumbled with Blue (1968), a fumbled attempt at a revisionist western, and Loot (1970), a fumbled attempt to film Joe Orton’s wicked black comedy. In 1977, he returned to Canada for Why Shoot the Teacher?, a charming adaptation of Max Braithwaite’s autobiographical novel about teaching at a one-room school on the Prairies in the 1930s, while his last notable production was a television adaptation of Paul Scott’s Staying On (1980), a coda to The Jewel in the Crown which reunited Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson thirty-five years after Brief Encounter (1945) as an elderly expatriate couple who remain in India after Independence.

I mention all that because I’m avoiding addressing directly the sheer awfulness of The Sky Is Falling. What can I say? Nothing works here and watching it filled me with embarrassment for the actors. I suppose it was an attempt to do something like Roddy McDowell’s Tam Lin (1970) or Barbet Schroeder’s More (1969), exposing the nihilistic decadence which was the residue of the counter-culture’s rejection of a moribund conformity. But while those earlier movies dug beneath the surface in their own different ways to discover the pain and confusion which had led their characters into dead ends, Narizzano’s movie just puts dysfunction on display – it’s little more than a freak show.

In a small Spanish town imbued with centuries of religion and superstition, with various cryptic ceremonies being enacted over Easter weekend (a number of animals are graphically sacrificed on camera), several aging expatriates – drug addicts and alcoholics – hang about, cling to memories of their former lives, and find themselves drawn to destruction by the arrival of a group of younger foreigners who view them with mocking disdain. The hapless losers are Chicken, a heroine addict given to extreme emoting, played by Dennis Hopper between The Last Movie (1971) and Mad Dog Morgan (1976); Terence, a former RAF officer who clings to past glory by wearing his old uniform, played by Richard Todd drawing on memories of all his officer roles in numerous British war movies; Allen, a bitter aging queen, played by Win Wells, who wrote the script; and Treasure, a former Hollywood star living in constant hope of being called back to Tinsel Town for another round of celebrity, played by Carroll Baker at the tail end of her long stretch as a star of Italian mysteries.

The new arrivals prey on these people’s vulnerabilities, seducing and rejecting them as intimations of death cast a shadow over the town. But I couldn’t say what story the movie is trying to tell as I was distracted by the overwrought performances and the air of cruelty towards the actors who are required to expose their insecurities in ways which cause embarrassment rather than revelation. I can’t recall the last time I saw a movie I disliked this much and I can’t imagine why Vinegar Syndrome unearthed it for this set; it seems they weren’t sure either as all the disk extras pertain only to the other two movies and the accompanying booklet contains only two essays, one each for Beatriz and El bosque del lobo, as if the set itself were embarrassed to have included it.

*

In the Earth (Ben Wheatley, 2021)

Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England (2013) is one of my favourite folk horror movies, a strange, dreamy evocation of the English countryside as a living force within which mere humans become lost. With the arrival of Covid, Wheatley returned to this theme by making another small movie out on the land – this time haunted woods rather than an open hillside. In the Earth (2021) opens by acknowledging the pandemic, with a masked figure walking along a deserted country lane, eventually arriving at a fenced compound where he has to be disinfected before he’s allowed in. Martin Lowery (Joel Fry) is a researcher who has been sent to find out what has happened to his old mentor (and lover?) Olivia Wendle (Hayley Squires) who has disappeared into the woods.

Guided by Alma (Ellora Torchia), Martin heads deeper into the woods in search of the place Olivia was last known to be. This suggests Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, with its journey upriver in search of Kurtz, someone who has lost himself and gone mad, and that is essentially the trajectory of Wheatley’s story – though the dichotomy here isn’t between civilization and savagery, but between science and the supernatural, or rather the numinous energy which animates nature.

Along the way, Martin and Alma encounter Zach (Reece Shearsmith), Olivia’s former partner, an artist who is trying to communicate with the ancient spirit of the woods named Parnagg Fegg. Although Zach is initially helpful, his madness gradually becomes apparent and he drugs the pair, performing odd surgical procedures on them and posing their unconscious bodies for disturbing photographs. When they finally manage to escape, they eventually find Olivia, who is using technology in her own attempts to communicate with Parnagg Fegg by blasting aggressive light-and-sound assaults into the woods. This all derived from her studies into the ways plants communicate among themselves, leading her to believe in a consciousness underlying nature.

Suggesting that people once had more direct access to this energy, there’s even an ancient stone circle nearby. As these characters clash and stir things up into a confusing eruption of events beyond their control, fraught with madness and violence, the film deliberately avoids any clear resolution. It’s core subject is the various ways we try to comprehend (and impose order on) a complex, multi-layered reality – science, reason, art and religion all come into play, but stubbornly refuse to cohere into a single, unified understanding – and those who push the hardest are likely to descend into madness.

While full of striking imagery, with interesting performances, In the Earth isn’t quite as satisfying as A Field in England. Whether its refusal to bring the various narrative and thematic threads together in the end stems from the uncertainty surrounding its making – none of us had any idea at the time about where the pandemic was going to take us – or perhaps was an intentional choice because the questions it raises are by their nature open-ended and irresolvable, it’s nice to see Wheatley getting back to the kind of material which served him well earlier in his career, after several not entirely successful diversions – his J.G. Ballard adaptation High-Rise (2015), the pointless Free Fire (2016) and an unnecessary remake of Rebecca (2020) for Netflix. Strangely, following this small, personal film, he took on a Hollywood effects block-buster – Meg 2: The Trench (2023), which seems utterly out of character.

*

Empathy, Inc. (Yedidya Gorsetman, 2018)

I’m partial to movies which use a strong concept and a well-written script to get around limited resources. The filmmaker’s imagination is a more valuable tool than a big budget. This applies to movies like Shane Carruth’s Primer (2004), Nacho Vigalondo’s Timecrimes (2007), Darren Aronofsky’s Pi (1998) and the like. Yedidya Gorsetman’s Empathy, Inc. (2018) combines low-budget and high concept with impressive assurance. Shot in striking, noirish black-and-white by Darin Quan, this is a fine piece of science fiction storytelling which follows the logic of its concept without a single narrative misstep.

Joel (Zack Robidas) is a venture capitalist who is scapegoated by his company when a project crashes. Having lost everything, he’s forced to head East and move with wife Jessica (Kathy Searle) into her parents’ house. It’s a prickly situation – they pressure him to get a real job – and he’s highly susceptible when he runs into an old acquaintance who has a proposition. Nicolaus (Eric Berryman) is involved with a small tech start-up which is developing a revolutionary new virtual reality device. This, he assures Joel, will change society for the better. Using the device will allow rich people to experience life directly the way the poor and downtrodden experience it.

Nicolas and his developer-partner Lester (Jay Klaitz) give Joel a brief demonstration, strapping him into the device with firm instructions just to observe what he sees without actually acting in the virtual space. When he enters the virtual realm, he finds himself inhabiting the body of a down-and-out old man in a barren room. It’s so vivid that he buys everything he’s being told. And so, going against Jessica’s express instructions, he talks his father-in-law into investing all his retirement savings into this “sure thing”.

Naturally nothing is what it seems. When he breaks into the Empathy, Inc., lab and sneaks another session with the machine, he finds himself on the street in a young man’s body, provoking a cop and engaging in an exhilarating chase. But an item in the paper makes him realize that this was not, in fact, a “virtual” experience – the machine actually puts its user into a real body, operating that body like a puppet. It doesn’t take long for him to understand that this has nothing to do with generating empathy – it’s a way for those who have the money to act without consequences, leaving their unfortunate puppets to deal with the fallout from their debauchery and crimes.

When Nicolaus refuses to return Joel’s investment, he finds himself in a deadly contest in which the stakes quickly escalate, with Joel and Lester switching bodies multiple times, with others being dragged in along the way. Gorsetman manages to keep everything clear as the identity-switching reaches a climax which puts not only Joel but also Jessica at risk.

It’s refreshing to see a science fiction movie which relies on its ideas rather than busy spectacle. Hopefully Gorsetman and co-writer Matt Leidner will come up with more work of this quality.

Arrow’s Blu-ray includes a commentary, some deleted scenes and a behind-the-scenes featurette which focuses on the shooting of the climactic sequence.

*

Flesh and Fantasy (Julien Duvivier, 1943)

Hollywood had already been attracting European filmmakers long before war broke out, so it’s not surprising that Julien Duvivier escaped to the U.S. in the early ’40s. What had caught the studios’ attention in particular were the romantic noir Pépé le Moko and the episodic romance Un carnet de bal (both 1937). The former was remade by John Cromwell as Algiers (1938), but Duvivier himself was put in charge of Lydia (1941), an American remake of the latter produced by Alexander Korda. This was followed by Tales of Manhattan (1942), in which a coat passes from one character to another, each temporary owner being the centre of a separate story, and then Flesh and Fantasy (1943), a three-part feature with supernatural overtones – which made Duvivier something of a specialist in portmanteau movies.

Although not the first of its kind, Flesh and Fantasy established the format for horror anthologies like Ealing’s Dead of Night (1945) and the series of Amicus movies released in the ’60s and ’70s, from Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) to From Beyond the Grave (1974). These movies generally gather several loosely related stories and tie them together with a frame that hopefully justifies linking them. In Duvivier’s film, based on stories by Oscar Wilde, Laszlo Vadnay and Ellis St. Joseph, the frame has a dyspeptic Robert Benchley telling his friend (David Hoffman) at the club about an unsettling dream. This leads the friend to grab a book from the shelf and read three stories which supposedly illuminate the link between dreams and fate… (There was originally a fourth story, but this was excised and later repurposed into a feature of its own called Destiny [1944], with additional material shot by Reginald LeBorg.)

Although Flesh and Fantasy displays the usual issues of anthology films – the uneven quality of the stories themselves, the rather arbitrary excuse for bringing them together, the problem of finding the best order for them (do you start with the strongest or the weakest? which makes the most satisfying ending?) – Duvivier creates a lot of atmosphere, with help from cinematographers Stanley Cortez and Paul Ivano. The film shares visual qualities with the Val Lewton productions at RKO and the expressionist films noirs which were beginning to emerge around the same time.

The first story has little to do with the theme vaguely expressed in the frame story. Henrietta (Betty Field) is a seamstress in New Orleans, bitter and lonely and contemptuous of the idea of love. Even with an absence of glamorous makeup and harsh lighting from below to emphasize her features (like someone telling campfire stories), the film has to work overtime to persuade the audience that she’s ugly and that’s why she’s never had a relationship.

One night during Mardi Gras, she’s approached by an elderly man who gives her a mask which makes her mysterious and alluring. A man named Michael (Robert Cummings) is attracted and they gradually fall in love through the evening. Of course, when midnight strikes and she has to return the mask, it turns out that she’s not ugly at all – a few hours of escape from her bitterness has revealed her true nature and there’s now romance in her future.

This is a rather trite Twilight Zone-like morality tale and, back in the club, Benchley doesn’t seem impressed, so his friend launches into the next story, adapted from Oscar Wilde’s Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime (1887). Aging attorney Marshall Tyler (Edward G. Robinson) attends a society soiree where Septimus Podgers (Thomas Mitchell) impresses everyone with his uncanny palm readings. Tyler is skeptical, but as he’s hoping to marry Rowena (Anna Lee), he lets Podgers take a look. A cloud descends and the palm reader doesn’t want to say what he’s seen; when pressed, he finally tells Tyler that he’s going to commit murder.

With this prediction hanging over him, Tyler becomes obsessed – he can’t marry Rowena until he’s gotten the murder out of the way, so he starts looking for a victim. But each scheme fails and he sinks into madness until, one night, he encounters Podger on a bridge and, since the palm reader has ruined his life, he kills him. This is where the film diverges from Wilde’s story. In the original, Podger’s death is deemed an accident and it’s revealed that he was a phony fortune teller; the maddened Arthur Saville gets away with murder, though it’s all a result of our innate suggestibility. In Hollywood, that would be unacceptable, so Tyler is nabbed by the police and hauled away in the throes of his madness.

Back at the club, Benchley absorbs the lesson that there’s danger in taking his nightmare too seriously and falling into a similar self-fulfilling trap. But his friend isn’t finished. He goes on to tell the story of Paul Gaspar (Charles Boyer), a circus performer whose act involves playing a drunk who ends up on a high-wire where he staggers about seventy feet above the ground without a net. One night, napping before the show, he dreams that he falls from the wire and as he plummets he sees a beautiful woman in the audience reacting with horror. Entering the ring, he loses his nerve and ends the act before his usual climax.

The circus sails for America and on the ship he encounters Joan Stanley (Barbara Stanwyck), the woman from his dream. He begins pestering her, but she’s not interested, at least at first. Eventually romance buds, but she has a secret and when the ship docks in New York, she disappears. But she’s there at the first performance and Paul gets back his nerve and successfully completes his act before she confesses that she’s done bad things and will be going to prison for a while. The police who’ve come to arrest her wait while she and Paul say goodbye, pledging their love and promising to wait for each other.

If Benchley hasn’t actually learned much during the evening, at least the stories have provided a distraction and he no longer feels dyspeptic. If the mix of stories fail to illuminate the (vague) theme brought up in the frame, they do give Duvivier an opportunity to play with moods and tones and, while some of the process photography in the third story is rather weak, he makes the most of studio resources to create slightly unreal versions of New Orleans, London and New York. And it’s nice to see actors like Robinson and Stanwyck again, even if their roles here are lighter versions of their more famous characters.

Vinegar Syndrome’s 2K restoration looks beautiful and comes with a commentary from Barry Forshaw and Kim Newman and a fifty-five-minute talk from filmmaker Christophe Gans covering Duvivier’s career, the impact leaving France during the war had on his work and his critical and commercial reputation, and the place of Flesh and Fantasy in his filmography. The disk is part of the companies new, and already eclectic, Vinegar Syndrome Labs sub-label and represents a step up in cinematic value from Curt Siodmak’s Curucu, Beast of the Amazon and Erle C. Kenton’s minor B-movie The Cat Creeps (1946).

Comments