Recent Viewing: April and May, part three

A Field In England (Ben Wheatley, 2013)

I missed Ben Wheatley’s third feature, Sightseers (2012), but found the first two interesting if not entirely satisfactory. Down Terrace (2009) is an odd black comedy about a gangster family that tears itself apart suspecting that there’s a police informer among them. It mixes standard gangster tropes with a kind of East Ender soap format which gradually escalates to high levels of absurdity. Kill List (2011) is about a couple of ex-soldiers turned hitmen who take on a contract which seems to have something to do with a child porn ring, but ends up turning into a Wicker Man-like plot leading to human sacrifice. This one remains frustratingly vague. Wheatley’s fourth feature, however, transforms that vagueness into a fascinating, almost hypnotic meditation on the mystical heritage of England – the kind of thing that Michael Powell explored in some of his best films: The Edge of the World, A Canterbury Tale, I Know Where I’m Going.

A Field In England (2013), set during the English Civil War, finds a handful of men trying to escape the violence only to be drawn into a deeper kind of madness as ancient forces envelope them and transform the world around them into something strange and unknowable. I’ll confess that the first time I watched it, I was confused and disoriented, having difficulty following the elliptical narrative (which takes place entirely in a single open field). But the film exerts a hypnotic pull which made me feel that there was something here worth pursuing, so I watched it again and then watched it with the commentary track (and then watched all the making-of featurettes on the Drafthouse Films Blu-ray). Eventually, I managed to clarify (more or less) what was happening in terms of the surface narrative, but it was the tone which really held my interest, that sense of powerful forces permeating the very soil of England and exerting strange influences on those who disturb them. Anyone who has taken the time to explore ancient sites like Stonehenge and Maiden Castle will have sensed something of this, the feeling of great age and mystery which has inflected religious, artistic and poetic thought throughout English history. What I found so unexpected was discovering this in a film by someone like Ben Wheatley, whose previous work, whatever its various merits, hasn’t exhibited anything like this depth before.

Shot digitally in pristine black-and-white and suffused with both humour and horror, A Field In England deals with the encounter of three soldiers – Jacob, Friend and Cutler – and Whitehead, the servant of an alchemist, with O’Neill, a man who has stolen mystical texts and objects and gone in search of a hidden treasure of supposedly great power. The four are drawn under this man’s influence and forced to aid in the search; as they dig they become consumed by madness and violence. In mood and theme, the film reminded me a little of The Stone Tape (1972), written by Nigel Kneale and directed by Peter Sasdy, with its gradual digging down through layers of time towards a primal, barely defined horror. Visually, it is somewhat reminiscent of Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s masterpiece, Winstanley (1976); as in that film, Wheatley has found a cast who have a convincing look for the period. Reece Shearsmith (of the League of Gentlemen) as Whitehead provides a focal point for the audience, while Michael Smiley is both menacing and amusing as the charlatan O’Neill; Richard Glover, called simply Friend, is something of a classic comic fool, although his propensity for repeatedly returning from death reinforces the dreamlike and troubling atmosphere of the film. Peter Ferdinando and Ryan Pope as Jacob and Cutler provide variations on men transformed by the war into killers, one with and one without a conscience. (Ferdinando has been turning up in some big budget movies – Snow White and the Huntsman, 300: Rise of an Empire – but his finest work remains his portrayal of the socially inept killer in Gerard Johnson’s chilling Tony [2009]).

It’s been a while since I’ve seen a film which has exerted such a hold on me, and I’ll no doubt be returning to it again before too long.

*

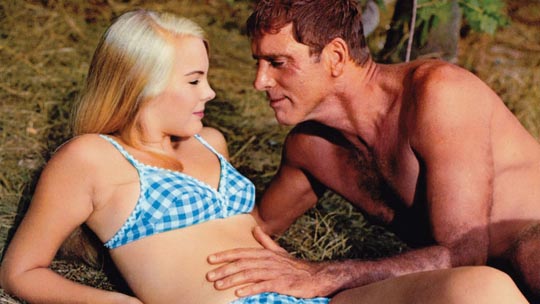

My Name Is Nobody (Tonino Valerii, 1973)

When I first saw My Name Is Nobody in the early ’70s, I’d had only limited exposure to spaghetti westerns, so it was something quite new and fresh to me. It was only later that learned that the film didn’t have a particularly good critical reputation. Based on an idea by Sergio Leone, and executive produced by the master, it is also reputedly at least partially directed by him – although there are obvious tonal differences between this elegiac comic epic and Leone’s signed work. Possibly because it co-stars Henry Fonda, or perhaps because lead Terence Hill had become an unlikely international star after the success of Boot Hill (1969), They Call Me Trinity (1970) and Trinity Is Still My Name (1971), Nobody was the only film directed by Leone’s former assistant director Tonino Valerii which got any kind of wide English-language distribution. A mixture of pastiche, broad comedy, and genuine homage to western tropes, both classical and spaghetti, the film has aging gunfighter Jack Beauregard (Fonda) trying to get out of the west to spend a peaceful old age in Europe, while cocky young upstart Nobody (Hill) keeps trying to stage manage a more spectacular exit for Beauregard in order to establish his own name. The film makes Leone-esque use of its desert landscapes and pushes its violent confrontations into realms of fantasy, but it also establishes and maintains an authentic melancholy regret for the passing of an age which is akin to (but gentler than) Peckinpah’s in The Wild Bunch. The “40th Anniversary” Blu-ray from Image is disappointing; the image is acceptable, although there’s no indication of any effort to restore the film, but surely it deserved some kind of retrospective features (commentary, documentary) if for no other reason than that the pairing of Fonda and Hill is so interesting in terms of conflicting acting styles and for what it represented in depicting a transition from classical gravitas to a more modern, smart-ass attitude to the genre. My Name Is Nobody was Fonda’s final appearance in a western (apart from a minor role in son Peter’s Wanda Nevada [1979]) and the actor uses the opportunity to sum up his long experience in that defining American mythology.

*

Mud (Jeff Nichols, 2012)

Jeff Nichols has a loose observational approach to storytelling which finds more of interest in character than events and his third feature, Mud (2012), is a leisurely coming-of-age story about a couple of boys who live on the banks of a tributary of the Mississippi in Arkansas. Like modern day Huck Finns, Ellis (Tye Sheridan) and Neckbone (Jacob Lofland) are more interested in hanging out on the river than going to school and doing their chores. When they discover a man hiding out on a small island, Ellis is drawn into an adolescent romantic fantasy which teaches him some important life lessons. If that sounds a little trite, it perhaps is in conception; but Nichols gets such rich performances from his two inexperienced young leads that the film becomes dramatically satisfying and emotionally engaging. The gradual exposure of the crippled relationship between Mud (Matthew McConaughey) and Juniper (Reese Witherspoon) scrapes away at Ellis’ illusions and pushes him out of the careless freedom of childhood into a harder reality which requires him to mature quickly.

*

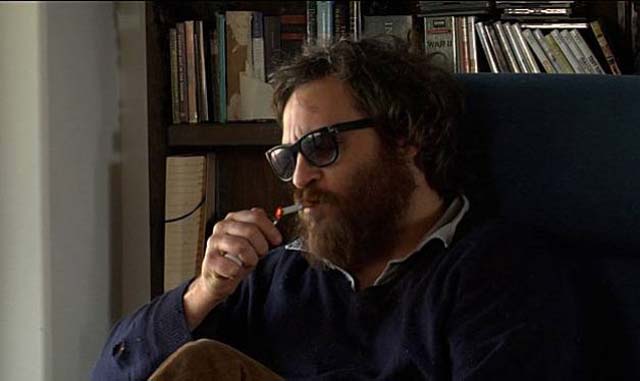

I’m Still Here (Casey Affleck, 2010)

I’m not sure how I would have responded to Casey Affleck’s I’m Still Here (2010) if I’d seen it cold when it was first released. At the time, it was greeted as an actual documentary; now it’s known to be an exercise in extreme public performance. In 2008, actor Joaquin Phoenix announced that he had been living a false life and was quitting acting in order to take up a career as a rap singer. Affleck followed the process, which included a legendary appearance on the Letterman Show in which it looked as if Phoenix was undergoing a serious breakdown. The film is a long, sustained train wreck. Or is it? Is it a fake documentary or a genuine documentary of a fake experience? Affleck and Phoenix maintain a straight-faced consistency throughout and the performance at its centre is both funny and disturbing, exposing a great deal about our relationship to celebrity as consumers and the psychological deformation of celebrities under our scrutiny. I’m Still Here dissects our fascination and implicates us in the damage inflicted on the famous by the mechanisms of fame.

*

Disco and Atomic War (Jaak Kilmi, 2009)

Jaak Kilmi’s Disco and Atomic War (2009) is an actual documentary which plays like one of Craig Baldwin’s found-footage alternate histories. Growing up in the ’70s and ’80s in Estonia, Kilmi was drawn into an illegal underground which helped the residents of Tallinn watch illicit television shows being broadcast from Helsinki, just 90km north across the Gulf of Finland. Although the Russian-backed government did everything they could to make these signals inaccessible, Kilmi’s father was an engineer who built devices for modifying TV sets to receive the broadcasts. It turned out that the Iron Curtain was hopelessly porous at this point and shows like Dallas undermined the official propaganda about the horrors of the capitalist West. (Kilmi would write up the weekly episodes and mail them to a young cousin in the south of Estonia, and she in turn would make the rounds of the neighbours’ houses to report on the doings of the Ewing clan; during the hiatus between seasons, Kilmi would make up his own scenarios to keep the show going.)

The thesis of this very funny and entertaining documentary is that western television provided a catalyst which ate away at the oppressive Soviet state, paving the way for the collapse of communism in 1989. The idea that trashy pop culture could have such momentous impact at first seems absurd to us who’ve been inundated with it all our lives, but seeing that culture through the eyes of a society where it was strictly forbidden, it does indeed take on the appearance of a liberating force. As in Baldwin’s masterpiece Tribulation 99, Disco and Atomic War provides an eye-opening alternate history which, beneath its surface absurdities, takes on a surprising air of truth. (The Icarus Films DVD also contains another Estonian documentary, the one-hour Lotman’s World [2008] by Agne Nelk; about renowned semiologist Juri Lotman, it’s a visually playful mix of biography, deconstruction and intellectual humour – combining documentary with some striking animation – and I have to admit I barely understood a word, although it did convince me of Lotman’s brilliance!)

*

The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968)

When I first saw Frank Perry’s The Swimmer (1968) on television sometime in the early ’70s I found it a rather uncomfortable experience. As someone with a heightened sense of social discomfort, the progressive public unravelling of Ned Merrill (Burt Lancaster) made me squirm. Seeing it again now on Grindhouse Releasing’s impressive Blu-ray, it turns out to be a fascinating if somewhat flawed work by a director whose career was wildly uneven (he started with the award-winning David and Lisa in 1962 – which I imagine would seem unbearably mawkish today – and went through arty independence to overblown commercialism, perhaps best-known now for his absurd, and absurdly entertaining, Mommie Dearest [1981]). Adapted by Perry’s wife Eleanor from a John Cheever short story, The Swimmer is a rare example in American cinema of a film which slides inexorably from social realism into psychological symbolism without ever appearing to shift stylistic gears along the way. The shooting and performance style remains constant, but the narrative elements gradually take on a less and less realistic appearance.

One Sunday afternoon, apparently-successful Connecticut businessman Merrill (perhaps the finest performance of Lancaster’s career) walks out into the backyard of a suburban house wearing only swimming trunks; greeted with welcoming surprise by old friends he apparently hasn’t seen for a while, it suddenly strikes him that it would be possible to “swim home” by portaging between all his neighbours’ pools … and so he sets off for a series of increasingly uncomfortable and disturbing encounters with old acquaintances, each revealing cracks in his sense of himself and the story he tells himself about his life (business success, happy family, adoring daughters). Initially people look at him a little strangely, signalling that they know something which he seems to be hiding from himself; gradually this vague uncertainty gives way to more and more open hostility and his struggle to maintain his sense of self becomes more fraught. We never learn the exact details of what traumatic things have destroyed his life (something to do with an accident involving his irresponsible daughters and the death of a neighbour’s son; the collapse of his business perhaps as a result of scandal), but when he finally makes it home to discover an abandoned, empty and decaying house, as at least one commenter has pointed out, it takes on something of the shocked revelation of The Sixth Sense – almost as if Merrill is a ghost unaware of his own death, working his way back through the layers of his life to a final awful awareness of his fate.

If The Swimmer isn’t entirely successful, that’s no doubt due to its troubled production as much as the limitations of its director. The disk includes a loose, discursive account of the making of the film which runs almost two-and-half hours, from which we learn that Lancaster and the relatively-inexperienced Perry (it was only his third feature) did not get along; that Perry was continually undercut by executive producer Sam Spiegel (who comes across as a colossal dick in this account); that despite the project originating with Frank and Eleanor Perry, it was eventually taken away from them with entire sections being recast and re-shot (by an un-credited Sydney Pollack). This last point is directly responsible for one of the film’s most glaring flaws, with California landscapes failing to match the original New England locations. Dramatically, the biggest change was the replacement of a crucial encounter between Merrill and a former lover, originally played by Barbara Loden and replaced by Janice Rule. It’s unfortunate that the original footage isn’t included on the disk (it probably no longer exists), because the description given by various interviewees makes the scene with Loden sound far darker and more dramatic than the version shot by Pollack, possibly depriving the movie of its most important moment of catharsis. But at least the final film escapes the happy ending the producer tried to impose.

The Swimmer as it stands is a fascinating glimpse of the rot beneath the surface of a complacent middle-class society. The story of its making suggests that it might have been something even better, although not necessarily in the hands of Frank Perry – Lancaster himself felt that it needed someone like Bunuel to pull it off successfully. What-ifs aside, it still seems like one of the most interesting and unusual films of its time.

Comments