More random notes: September 2016

This has been a diffuse kind of month. Days are growing shorter (it was a shock last week to realize that it was still full dark when I left to catch the bus to work in the morning; always a gloomy prospect, it means that I won’t be rising in daylight again for more than six months); work is as tedious as ever; and there are stressful family matters which have been weighing on me for several months, leaving little extra energy for what I really enjoy doing – watching movies and writing about them on this blog.

Lately, I’ve been re-watching familiar things, kind of like eating comfort food; it requires less energy while providing the reassurance of already experienced emotions. Among others, I revisited Brad Bird’s excellent debut feature, The Iron Giant (1999), in its new Blu-ray edition: seeing again such a fine piece of classical drawn animation is a reminder of a craft almost lost in the subsequent tide of computer animation. Of course, there’s a lot of really good CG, but no matter how good it is, it lacks the tangible, tactile quality of hand-drawn artwork (or stop-motion). In the case of The Iron Giant, that craft is put to the service of a witty, inventive script based on Ted Hughes’ novel for children. The adaptation not only shifts the setting from England to the United States, it eliminates the colossal alien threat which the robot has to defeat and focuses instead on the deeply rooted social and political paranoia of the ’50s, a time when everything new provoked anxiety and pushed nations dangerously close to nuclear war. The Iron Giant stands with Ratatouille (2007) as Bird’s finest work.

*

With the arrival of the 50th anniversary of the debut of Star Trek in 1966, I’ve been making my way through the original series again for the first time in years. Gene Roddenberry’s hopeful space opera premiered just weeks before I arrived in Canada as a boy and watching it on a small black-and-white TV set was one of my first memorable experiences in the new country. Like any kid my age, I was hooked by the spaceships, the aliens, the phasers and photon torpedoes, while I may not have been fully aware of the mixture of comedy and social commentary.

It wasn’t until years later that I finally saw the show in all its garish colour. That colour actually makes it look tackier than I remember from those first B&W viewings, something only emphasized by hi-def transfers on the Blu-rays. The plywood walls of the Enterprise, the styrofoam rocks and painted backdrops on the studio-set alien planets, the frequently unconvincing matte paintings, all stand out in their artificial glory, and yet that tackiness is just one of the show’s many charms; others being its naive earnestness, its almost childlike insistence on the superior values of human emotion and irrationality, its emphatic insistence on values of equality and tolerance in terms of race and nationality even while displaying rampant sexism in its treatment of almost always subsidiary female characters. Even though Nichelle Nichols’ Uhura was a constant presence on the bridge, her tight skimpy uniform signaled the real reason for her inclusion as she served as little more than a switchboard operator. The ubiquity of revealing outfits for female crewmembers and guest stars alike harked back to the eye-catching covers of pulp magazines rather than looking ahead to a society of genuine equality.

Familiarity also makes one forgiving of the overwrought, hammy performances, dominated of course by William Shatner’s distinctive use of inappropriate pauses and emphases, often delivered in a torn shirt, or even completely shirtless. Given that Shatner had previously displayed genuine skill in serious performances in numerous TV shows, as well as a supporting role in Stanley Kramer’s Judgement at Nuremberg (1961) and as the star of Roger Corman’s finest film, The Intruder (1962), it was perhaps the fantasy element of Star Trek, its disconnection from mundane reality, which provided license for him to give free rein to the inner Shatner which has been on full display during the subsequent fifty years.

For audiences which came along later, introduced to the Roddenberry universe through the movies in the ’80s and the various subsequent series from Next Generation through Deep Space Nine, Voyager, Enterprise, to the execrable new theatrical reboot, the original series may be perceived as a creaky embarrassment. But for those of us who saw it in the day, it remains for all its infelicities and absurdities, the one true Trek, its shortcomings treasured just as much as its occasional imaginative riches.

This difference in perception is behind the irritating revisionism displayed on the Star Trek: TOS Blu-rays, an attempt to do to the series what George Lucas has done to the first three Star Wars movies, as well as American Graffiti and THX 1138: the show’s owners hired SFX technicians to “improve” all the episodes by digitally replacing the original imagery. This is not just a matter of spiffing up all those Enterprise flybys: new digital matte paintings have been added to the poky planet surface sets, day has been changed to night and vice versa because somebody decided there were continuity problems, phaser blasts and photon torpedoes have been made more impressive (supposedly). There are numerous problems with this kind of tinkering, as I’ve talked about before on this blog, but the biggest issue is that it fundamentally changes what the show was and remains: a display of what was possible at the time of its creation with the financial and technical resources available to the people who made it. It erases the history of what those people had managed to do, arrogantly proclaiming that we’re much better at this kind of thing now. There’s a condescension to this kind of vandalism, a sense of embarrassment that somehow the original creators hadn’t done a good enough job.

The rationale for this is that today’s audiences just won’t accept the “inferior” effects and that simply erasing all that work is less effort than trying to educate an audience about things like history and context. But there’s an odd ancillary effect to this meddling: it implies that what’s most important about the show is the visual effects while simultaneously saying that the original effects are wretchedly inadequate. But such revisionism doesn’t change the content, the hammy acting, the overwrought, often preachy scripts, and to someone who desires slicker visuals, those fundamental elements of Star Trek, the things which largely made the show what it is, will still look clumsy and dated.

As obnoxious as this is, at least the people behind “revising” Star Trek: TOS had the sense to keep the original versions on the disks, allowing those of us who care to see the show as it was made – unlike George Lucas who, with dictatorial brutality, has obliterated the movies which drew countless fans and forced on those fans versions which conflict with their own memories.

*

After a lengthy diversion, I also recently got back to Criterion’s Zatoichi set and resumed making my way through the series. The formula never gets tired for me, with Zatoichi wandering from town to town, reluctantly getting drawn into someone else’s troubles with the local gang bosses, and finally righting wrongs in a spectacular fight against massed enemies – usually in confined spaces like winding back alleys or a maze-like series of rooms and corridors whose paper walls get sliced by flashing sword blades. In each episode, I anticipate as much as the climactic battle the dice scene in which the amiable masseur uses his preternatural skills to turn the tables on those who think it’s easy to take advantage of a blind man (just one of many essential ingredients missing from Takeshi Kitano’s disappointing 2003 remake).

*

Less felicitous is William Friedkin’s The Guardian (1990), a belated attempt to recapture the supernatural glories of 1973’s The Exorcist. Friedkin and writer Stephen Volk can’t pry anything particularly original from Dan Greenberg’s novel about a young middle class couple who hire a live-in nanny to look after their infant son. As we all know, live-in nannies are always trouble – either psychotic killers or agents of the Devil. In this particular case, Camilla (Jenny Seagrove) happens to be the servant of a Druid deity which lives in the Hollywood hills in the form of a giant people-eating tree. The movie works as neither genuine horror nor parody, instead coming across like a ’70s TV movie-of-the-week made long after that genre had passed its sell-by date.

*

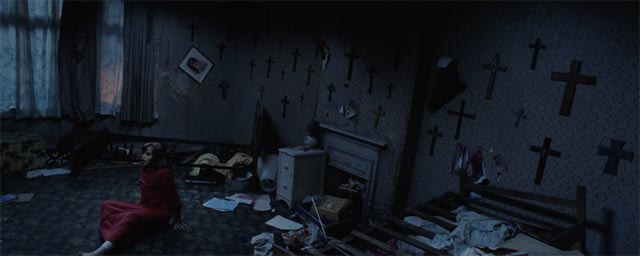

Perhaps it’s the setting of James Wan’s The Conjuring 2 in North London in the 1970s that brings to mind the Stephen Volk-scripted Ghostwatch (Lesley Manning, 1992), the great BBC “live reality show” about a poltergeist haunting. Like Wan’s excellent 2013 horror movie, the sequel is based on the supposed real-life casebooks of supernatural investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren. The source of the new film is the widely publicized Enfield Poltergeist case which occurred between 1977 and 1979 in which the Hodgson family were plagued by the usual physical effects associated with the noisy ghosts, which as usual occurred around adolescent children. The case was prominently covered in the press and on television, with members of the Society for Psychical Research convinced that the manifestations were genuine while skeptics accused the two Hodgson daughters of faking it all.

The movie naturally leaves no doubt of the reality of the haunting, initially positing that a former resident of the house resents the family’s presence before ramping things up with the appearance of a full-blown demon who must be defeated by the Warrens at the risk of their own lives. In straining to convince the audience of the reality of some pretty standard genre elements, Wan and his co-writers (Carey Hayes, Chad Hayes and David Leslie Johnson) tend to overdo things in a way they avoided with the more subtly creepy first film. This one is bigger, louder, and less convincing. But that said, Wan continues to display a genuine affinity for the genre, generating atmospheric effects and, perhaps more importantly, drawing good performances from his cast. The two girls (Madison Wolfe, Lauren Esposito) and their mother (Frances O’Connor) are particularly good, with Simon McBurney and Franke Potenta taking things seriously as, respectively, the chief investigator who believes and the psychologist who dismisses it all as a hoax. The disk includes a brief featurette in which the Hodgsons appear, claiming that it’s great to finally have their true story told in the movie.

*

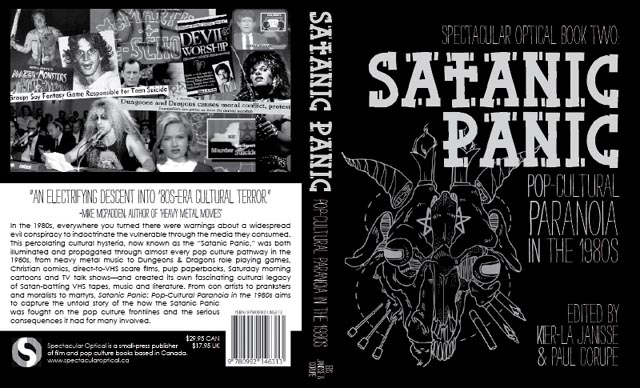

And speaking of demonic horrors, I recently read the new FAB Press book Satanic Panic: Pop-Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, co-edited by Kier-la Janisse and Paul Corupe. This collection of essays deals with the strange moral panic which swept the U.S. and England throughout that decade, signaled to a degree by the huge success of The Exorcist, a film which linked the social upheavals of the ’60s and so-called youth rebellion to the influence of actual devils. The media jumped on the sinister influence of horror movies, heavy metal music (and its various genre off-shoots) and drugs, stirring up middle class fears about the decline of western civilization which spurred, and ran in parallel with, the rise of the religious right.

Paranoia became a lucrative industry, fomenting the largely debunked “recovered memory” movement which asserted that the Satanic abuse of children was rampant throughout society, with members of secret organizations supposedly breeding babies specifically to be sacrificed during dark rites. The book’s various writers approach these events from a number of angles, some more successfully than others. Some of this was already familiar to me, so I was more interested in the chapters on things like fundamentalist comic books and “white metal”, an attempt to appropriate supposedly inherently evil forms of music to convey a Christian message. The chapter on Satanism and technology in movies like Evilspeak (1981) is the longest but least coherently argued, but the most surprising and illuminating essay, Adrian Mack’s False History Syndrome: HBO’s “Indictment: The McMartin Trial”, comes late in the book and reframes pretty much everything which has come before.

The McMartin case centred on a family running a pre-school daycare who were accused of massive ritual sexual abuse of the children in their care. Those accusations became larger and more bizarre as the case proceeded (one of the longest trials in U.S. history), dragging in the now familiar Satanic overtones, complete with human sacrifice. What Mack manages to make clear is that the excesses of Satanic paranoia actually served to conceal possibly more disturbing real-life horrors, an argument which gains credence from revelations in the past few years of just how widespread organized paedophilia was (and one assumes still is), with the exposure of people like Jimmy Saville and Rolf Harris in England, prominent pop culture figures whose celebrity enabled them to indulge in decades of predatory sexual activity with children, and who were protected by powerful institutions more concerned with their own reputations than with stopping those crimes. By playing up the absurdity of the Satanic accusations, Mack argues that the appearance of an irrational witchhunt may well have obscured genuine abuses, with victims painted as disturbed liars and possible perpetrators transformed into heroic figures standing against the irrationality sweeping through society.

Satanic Panic is an interesting addition to Kier-la Janisse’s on-going project to dissect the underlying psychological truths embedded in pop culture, best exemplified by her remarkable House of Psychotic Women, which combines film criticism with a harrowing personal memoir.

Comments