Raro Video and Italian genre cinema

In the short history of DVD, many companies have come and gone. The major distributors are still around, of course, and public domain companies like Mill Creek seem to be surviving despite the generally poor quality of their output. But for collectors, it’s the smaller “boutique” companies that have offered some of the most exciting titles.

Criterion is the gold standard in region 1, but on the lower tier Anchor Bay used to be an excellent source of genre titles before major staff changes diminished it, with former AB producers splitting off to form the excellent Blue Underground. Zeitgeist, Facets, Milestone, Kino, First Run – these companies have kept up a steady stream of classics, independent and foreign films with disks of varying quality. Australia has Madman, which puts out fine editions of Aussie features like Ted Kotcheff’s Wake In Fright (aka Outback, 1971) and Philip Noyce’s Backroads (1977), as well as “foreign” films like Wim Wenders’ Road Movies “trilogy” (Alice in den Stadten [1974], Falsche Bewegung [1975] and Im Lauf der Zeit [1976]) and Peter Greenaway’s ambitious The Tulse Luper Suitcases trilogy (2002-2003: as far as I know they’ve never been released anywhere else on DVD, apart from a Dutch edition of the first film, The Moab Story, in 2004). And Britain and Europe have numerous companies, like Blaqout and MK2 in France, Editions Filmmuseum in Germany and Austria, the BFI, Eureka/Masters of Cinema, Second Run and Artificial Eye in England.

But one of the best of these, the Italian company No Shame, sadly vanished a few years ago. This company was prized not only for the range and quality of its releases, but for the fact that it opened a North American division to release many of its titles in region 1.

In my collection, I have their editions of Antonioni’s first feature, Story of a Love Affair (1950); Bertolucci’s Partner (1968), a rather strained and difficult political film; Pietro Germi‘s The Railway Man (1956), a terrific realist drama about struggling workers in post-war Italy (it was only after I discovered Germi through this film that Criterion subsequently released his two more famous satirical comedies, Divorce Italian Style [1961] and Seduced & Abandoned [1964]); Francesco Maselli’s dissection of bourgeois leftist intellectual hypocrisy, Open Letter to the Evening News (1970); and Damiano Damiani’s excellent fact-based mafia story, The Most Beautiful Wife (1970), as well as Umberto Lenzi’s searing Almost Human (1974) and various other poliziotteschi by Stelvio Massi and others. I also have No Shame’s sets of gialli by Luciano Ercoli and Emilio Miraglia, and although they weren’t released in region 1, I bought copies of the Italian editions of Riccardo Freda & Mario Bava’s Caltiki the Immortal Monster (1959) and Sergio Martino’s Island of the Fishmen (1979) from on-line vendors.

Most of these disks were enhanced with extensive extras, in some cases rivaling Criterion but on a much smaller budget. In several cases they included entire second features with some kind of relation to the main title. But the disappearance of No Shame wasn’t really a surprise: their output was amazingly eclectic and they put a great deal of effort into their releases. And for these very reasons, it must have been financially difficult for them to remain in business as long as they did.

I read somewhere that a new company that turned up a couple of years back, MYA, is actually No Shame reborn in a less ambitious form. If true, it’s rather sad because MYA shows little ambition, focusing on lesser genre titles, often with poor quality transfers, with no expenditure on supporting material of any kind.

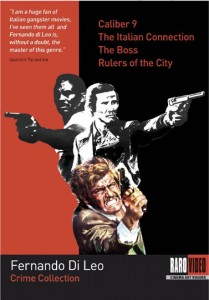

But now another company is stepping in to fill that void. Like No Shame, Raro Video is an Italian company which is just now opening up a North American branch and with its initial offerings, Raro has announced quite firmly that it shares No Shame’s original ambitions. These titles include a fine edition of Fellini’s highly personal documentary I Clowns (The Clowns, 1970); Antonioni’s third feature I vinti (The Vanquished, 1953), which will go nicely in my collection with the new Masters of Cinema editions of his second and fourth films, La signora senza camelie (1953) and Le amiche (1955); Francesco Barilli’s giallo The Perfume of the Lady in Black (1974); and a box set of poliziotteschi by Fernando Di Leo, a director I wasn’t previously familiar with.

The Fernando Di Leo Crime Collection is an enjoyable set of somewhat rough-edged thrillers by a director who lacks the polish of a Damiani or the visceral power of someone like Lenzi at his best. Working from his own scripts, Di Leo combines sometimes clumsy dialogue scenes, frequently impressive action sequences, and occasional poorly integrated political commentary (here he lacks Damiani’s ability, in such films as The Most Beautiful Wife and How to Kill a Judge [1976], to make the politics integral to the narrative) into energetic, generally well-constructed narratives about disillusionment and betrayal among criminals.

As with so many Italian crime films, all four of the thrillers in this set take place in a harsh, amoral universe ruled by ubiquitous criminal organizations whose influence permeates every level of society, including those who supposedly make, uphold and enforce the law. The heroes of this world are also criminals, perhaps just not as bad as their bosses. In Milano Calibro 9 (aka Caliber 9, 1972), Ugo Piazza, a small-time gangster just out of prison seems only to want to get on with a quiet life, but his former bosses believe he stole a large sum of money from them and are determined to get it back despite his insistent denials. He finds himself caught between the gang and the police, subjected to beatings and abuse, as he calmly and quietly manipulates everyone around him into destroying each other until, just as his long-held plan seems to be coming to fruition, he’s destroyed by a final unexpected betrayal. Milano Calibro 9 is held together by the laconic lead performance by comic actor Gastone Moschin (while watching it, I kept thinking that it was ripe for a remake starring Jason Statham). While it was a pleasant surprise to discover the lead villain being played by old favourite Lionel Stander, he was unfortunately not given a lot to do – obviously imported for the “name value” and kept on the payroll for only a couple of days.

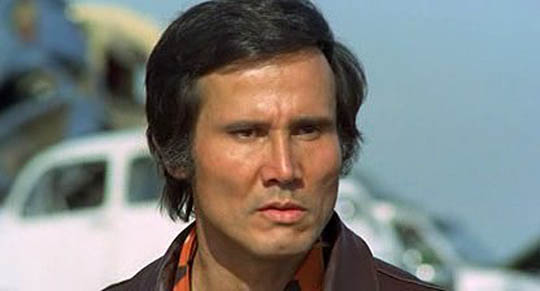

The use of non-Italian actors was standard practice back in the ’60s and ’70s (i.e. Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef in spaghetti westerns), so it’s not surprising that chisel-featured Henry Silva shows up in the next two films in the set: La Mala Ordina (aka The Italian Connection, 1972) and Il Boss (aka The Boss, 1973). In the first of these, Woody Strode (featured in many a spaghetti western) shows up as Silva’s almost-silent hitman partner, and more surprisingly we get the great Irish actor Cyril Cusack as a mob boss in New York who sends the two killers to Italy to make an example of a small-time pimp, Luca Carnali (Mario Adorf, who had a supporting role as one of Ugo Piazza’s principal tormentors in Milano Calibro 9), though the nature of Carnali’s transgression isn’t clear.

La Mala Ordina is the best film in the set, partly because of the main character – an amiable pimp trying to make money to provide for the young daughter who’s being raised by his estranged wife – and partly because Di Leo keeps the narrative motor obscure from both Carnali and the audience for much of the running time; we, like Luca, don’t know why these people have come to kill him and so we become fully invested in his struggle to survive and eventually fight back. In addition to the strong narrative, there’s a terrific, intense chase scene half way through the film, on foot, in vehicles, on foot again, shot and edited with great energy which embodies the crazed anger of Carnali as he’s finally driven to kill. Unlike most Hollywood movies, Italian genre cinema shares with Hong Kong movies a willingness to kill likeable and innocent characters and it’s one such transgressive moment in La Mala Ordina that drives Carnali to stop running and turn to face his tormentors in a final bloody showdown.

Although the third film, Il Boss, starts with a spectacular sequence in which hitman Silva uses a grenade launcher to wipe out a screening room full of mafiosi watching a porn movie (an acknowledged influence on the movie theatre finale of Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds [2009], just as the hitman team in La Mala Ordina were a model for the Travolta-Jackson team of killers in Pulp Fiction [1994]) and the great Richard Conte appears as the mafia boss who talks endlessly of loyalty even as he betrays everyone around him, this dissection of the lies behind the mob’s declarations of honour is undermined somewhat by Silva’s impassive performance and by the problematic depiction of the main female character, Rina D’Aniello (Antonia Santilli). Despite Di Leo’s claims that he was trying to show a strong, independent woman in complete control of her own sexuality, what comes across is a coarse fantasy about a woman who, after being raped by her kidnappers (something she obviously enjoys), becomes an insatiable nymphomaniac. Despite a fairly well-constructed plot about an insider who turns against his bosses after being betrayed, Il Boss leaves a sour taste in its wake.

The final film in the set, I Padroni della Citta (aka Rulers of the City, 1976), is lighter and more enjoyable. It centres on a cocky young hood named Tony (Fassbinder favourite Harry Baer) who teams up with another young enforcer, Ric (Al Cliver), and an older man, Napoli (Vittorio Caprioli), to take a lot of money from mob boss “Scarface” Manzari (Jack Palance). What Tony doesn’t know is that Ric has another motive for taking on Manzari, as revealed in the film’s prologue in which a young boy sees Manzari murder his father. The combination of a lighter comic tone and Palance’s typically enjoyable hammy performance make Padroni a satisfying conclusion to Raro Video’s introduction to Fernando Di Leo’s work, while the set as a whole, which includes documentaries on the individual films and on Di Leo and his career and influences, makes one optimistic about the prospects of seeing an interesting range of Italian movies on DVD in the near future.

Comments