Restoration and Revisionism

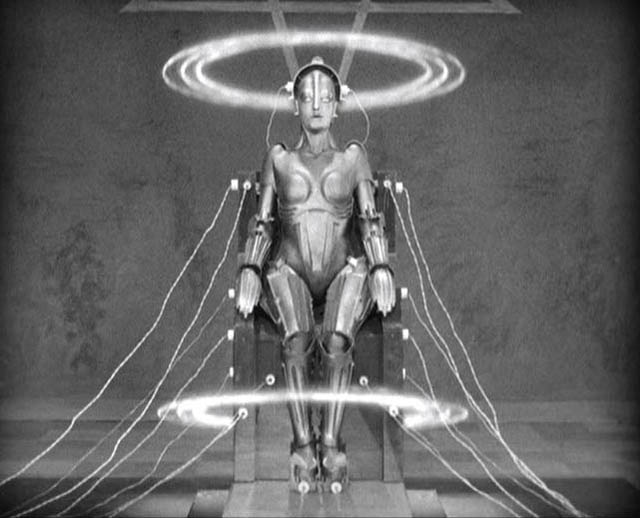

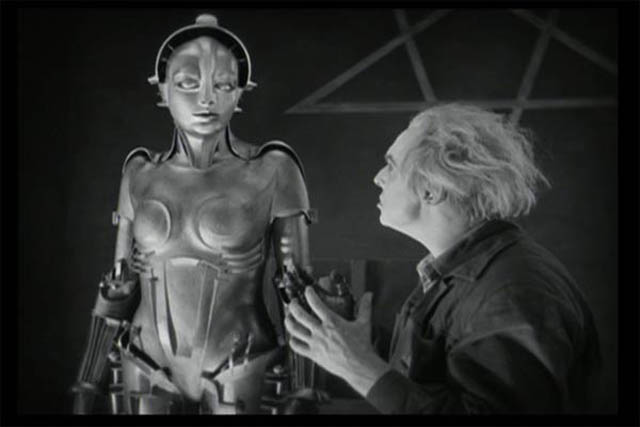

In their joint commentary track on the Masters of Cinema DVD/Blu-Ray release of the newly restored Metropolis, David Kalat and Jonathan Rosenbaum express some concern that this new version will cause the disappearance of all previous versions. Why should this be a problem? After all, the “restored” Metropolis is the closest we’ll ever get to Lang’s original work which premiered in Berlin in January 1927. Well, as they point out, the various previous truncated (the Paramount/Channing Pollock edit which became the “official” version later in 1927), modified (the 1984 Giorgio Moroder rock version), and various partially restored versions are the ones which sustained interest in the film for 80 years; those versions are the ones which people saw and became fascinated with, so to erase them from memory by enshrining the new, restored version as the single, definitive one in a way effaces all our long held memories of the film.

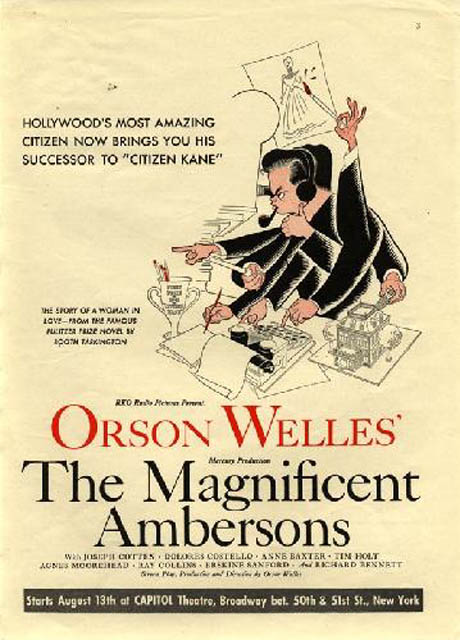

When the first attempts were made to piece together a more comprehensive version in the ’60s and ’70s, such restoration attempts were still rare. It was only with the greater accessibility of movies on home video (indicating to distributors the renewed economic value of old films), in conjunction with the explosion in film studies from the late ’60s on, that any kind of desire to search for lost and broken films and restore them became more widespread. Before this we would simply experience a film as a finished artifact, with little thought of how it might have been different – well, apart from a few special cases like Welles’s butchered Magnificent Ambersons.

But as things changed with the rise of archives and restorations, the existence of variant versions also surfaced – we now have different versions of Murnau’s Faust and Sunrise, for instance, based on different source elements, because it was the practice in silent days to create multiple original negatives (either through the use of multiple cameras, or using different takes from a single camera) for domestic and foreign markets. And of course, in the early sound era, in Hollywood and Europe companies would shoot simultaneous versions in different languages – which is why we have George Melford’s superior Spanish version of Dracula, shot on the same stages as Tod Browning’s movie, with different actors working from a translation of the original script; a French version of Lang’s Testament of Dr. Mabuse; and even an English version of his M.

And in a sense, different versions were also created after a movie went into distribution, because various regions had their own censor boards and would cut up prints according to their own standards. Even now, this results in British DVD releases of horror and exploitation films which are different from the North American versions … and I once had a made-in-Ontario VHS copy of George Romero’s Day of the Dead which had been reduced to complete incoherence because the censors had tried to cut out every frame of gore, which meant that virtually every scene was a bizarre mess of jump cuts, with fragments of dialogue missing so that nothing anyone said made sense any more.

But what is largely a new development of the past decade or so, courtesy of the advent of DVD, is distributors releasing multiple versions of many titles almost simultaneously – theatrical cuts, unrated cuts, director’s cuts … a process which now gives viewers the choice of which version of a film to watch and the ability to decide which is their own personal “official” version. While in most cases, differences aren’t that substantial, often a matter of a few extra bits of violence or sex not permitted in theatres, sometimes it’s almost like seeing a different movie …

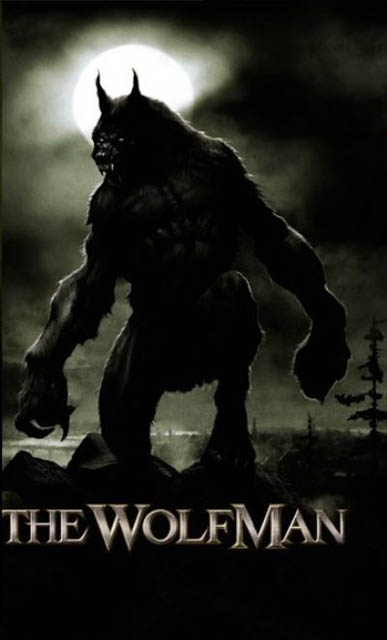

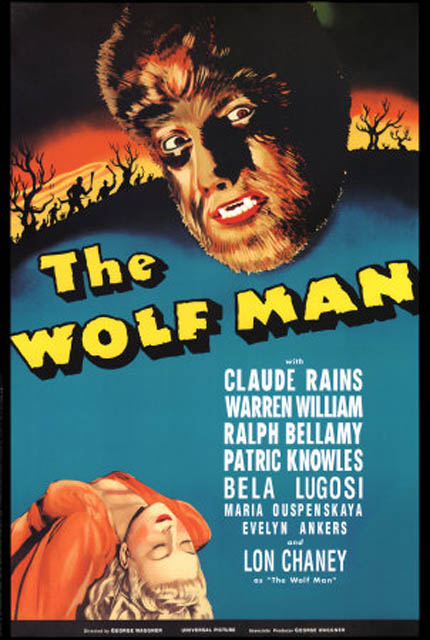

Tim Lucas, in Video Watchdog #158, commenting on the Blu-Ray of the new Wolfman (2010), speaks of how these multiple versions, surrounded by ever more elaborate “special features”, affect our experience of a movie: “The mind boggles – not so much from how much these features stand to enhance the viewing experience but from how much they stand to eclipse it. It already complicates or dilutes our understanding of what is proposed by the title “The Wolfman” (distinct from 1941’s The Wolf Man) by issuing two different cuts of the picture … Has anyone stopped to wonder what alternative endings do to the viewer and his recollection of a feature film?” The loss of the definitive diminishes our experience of a film – we can’t recall a singular experience if our memories are cluttered with deleted/alternate scenes, unused endings, variant cuts …

And yet, because movies are often rushed into theatres before really being properly finished, or are reworked by distributors who feel that they need to be made more commercially viable, sometimes the original theatrical release is not necessarily the best version. So our personal film histories become almost self-made.

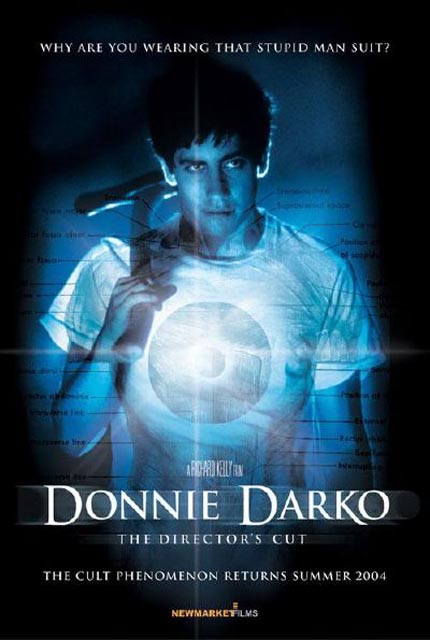

I’m one of those people who fell in love with Donnie Darko (2001) the first time I saw it, but I was eager to see the “director’s cut” when it came out on DVD because I assumed that Richard Kelly must have improved things he wasn’t entirely satisfied with in the original release. However, the newer version did nothing for me – the slicker effects, some changes in the music, some altered or added scenes – somehow it no longer grabbed me. So I went back and re-watched the original and loved it all over again.

When I first saw Alex Proyas’s Dark City (1998) I thought it was one of the best SF movies of recent years, gorgeously designed, built around an intriguing idea. Then some years later, along came the “director’s cut” and the information that the distributor had made a number of major changes because they were afraid an average audience might be confused. Turned out that Proyas’s version was even better than the movie I already loved, so while the original theatrical version of Donnie Darko is the only one I’ll re-watch, the opposite is true of Dark City.

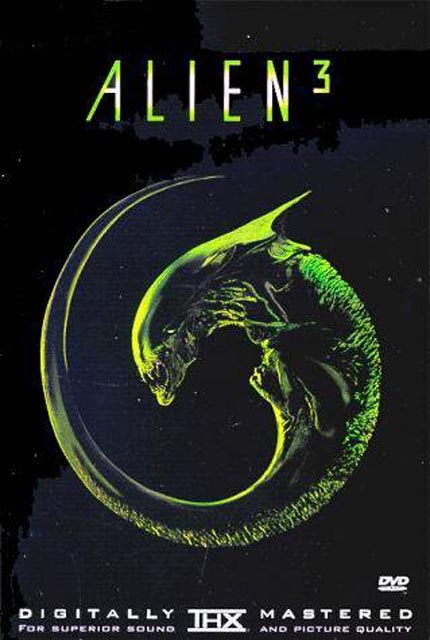

James Cameron’s extended version of Aliens (1986) is weaker than the original version, largely because of the inclusion of that sequence on the planet during which a prospector discovers the egg chamber and we see exactly what happens to the colonists before Ripley and the Marines arrive … talk about undermining the suspense. But the longer, not-quite-finished cut of David Fincher’s under-rated Alien 3 (1992) is a richer, darker, more compelling film than the release version.

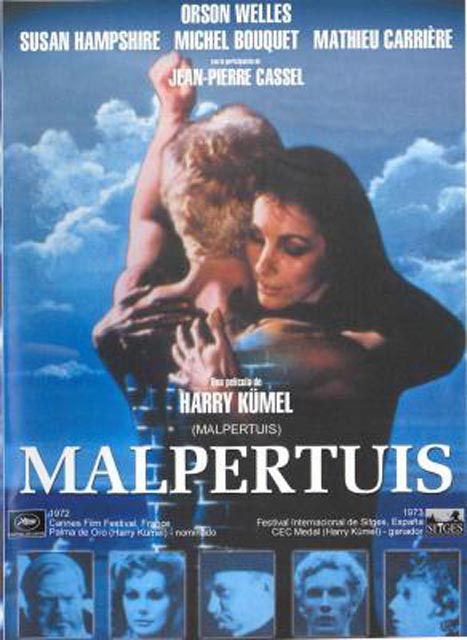

There are two versions of Harry Kuemel’s Malpertuis (1971), his own original which is a wonderful dreamlike fantasy based on the surrealist novel by Jean Ray – and the shorter version, recut by the producer and premiered at Cannes with disastrous results. Because the producer thought the film was too strange and attempted to turn it into a “coherent”, linear narrative, completely destroying the dreamlike structure.

Mario Bava’s work has suffered this kind of revisionism at least twice, seeing his gorgeous, Bunuelian fantasy Lisa and the Devil (1974) transformed into a travesty called House of Exorcism by producer Alfredo Leone, with the body of the original essentially turned into dream sequences inserted into a crude and silly, post-Exorcist pea-souper. No doubt Leone made more money with his version than he could have with Bava’s, but surely nobody now would choose it over the original.

A stranger fate was suffered by one of Bava’s finest films, his 1974 bid to move beyond Gothic horror to contemporary thriller with Rabid Dogs. This film remained uncompleted in his lifetime because of the collapse of financing; in the ’90s, the lead actress Lea Lander financed the editing and completion of the film, one of the grimmest, most cynical and gripping thrillers to come out of the golden age of Italian genre filmmaking. This story of a robbery gone wrong and a hostage-taking plays out almost entirely inside a small speeding car; it’s a directorial tour de force and a flawless piece of storytelling. But then, for some inexplicable reason, Bava’s son Lamberto in collaboration with Alfredo Leone, set out to destroy it by turning it into some kind of standard movie, opening the story out with completely unnecessary scenes of police activity and a woman waiting in an apartment for news of her missing child. All the film’s rhythms are destroyed and the mediocre results were stuck with the boringly generic title Kidnapped.

Then, of course, there’s Ridley Scott who seems to have a whole parallel career in releasing “director’s cuts”. I found Kingdom of Heaven (2005) a complete bore when I saw it in a theatre, but decided to watch it again when the longer “director’s cut” arrived on DVD and it turned out to be a rich and involving historical epic on the theme of the stupidity of fighting wars and the perniciousness of the sense of righteousness which drives them. And there are now no less than five versions of Blade Runner (1982), from the unfinished preview version to “The Final Cut”. When I first saw the film (which again, I loved at first sight), there were two things that I felt diminished it: Harrison Ford’s flat narration and the happy ending. I came out of the theatre thinking that if only they’d remove the voice over and end the film with the closing elevator door, it would be perfect. Well, Scott did that with the first “director’s cut”, and I was happy. And then years later, he went back and did a bit of a digital polish, not altering the film, just tweaking a few shots (in particular that glaringly inappropriate one of the dove flying up into blue sky). And I was actually even happier.

Which is more than I can say about the most egregious instances of this kind of dubious revisionism: the handiwork of George Lucas who, in lieu of any kind of creativity, seems to have dedicated himself to erasing his own (and his multi-million member audience’s) past by digitally altering everything he has ever done. He tweaked American Graffiti (1973) because he didn’t like some of the colours and backgrounds from the location shooting. Then he began to rework his Star Wars movies because he no longer liked the special effects – which historically are the one feature of the films which warrant any kind of notice. Not to mention deciding to make Han Solo a “nicer guy” by not having him shoot first in the bar, delaying his shot so that he kills only in self-defence. All of this might not matter so much if he had been willing to keep the originals available alongside the altered versions (as Spielberg did with E.T.). But Lucas doesn’t want anyone to see the originals any more (yes, there was one dual release a few years back which included unrestored, non-anamorphic, low grade copies of the original versions, which seemed almost like a slap in the face to the fans who kept asking for them); apparently he believes that since these are his films, it doesn’t matter how all those millions of viewers who grew up with the series feel about them.

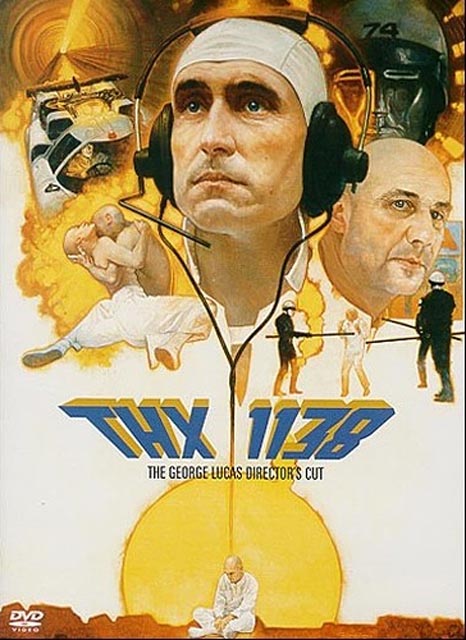

The worst case of all is his digital destruction of his first feature, THX 1138 (1971), a brilliant melding of low budget science fiction and the visual and audio montage techniques of Arthur Lipsett, a film whose meanings are embodied not just in the fairly simple, even familiar dystopian story, but in every aspect of the technique. A technique he has completely erased with glossy, big budget digital tampering. It’s sad that he is apparently incapable of appreciating what he accomplished in 1971, but it’s unforgivably egotistical that he has no consideration for the audience that made his work a lasting cult favourite. All I can say is I’m glad I still have my old laserdisk copy of the original.

Comments