The Exotic Ones: exploitation and religion from the Ormond family

If Indicator’s Michael J. Murphy box set is an act of film archaeology, what it has unearthed is a collection of specimens with clear connections to known lineages. What to make, though, of their new box set From Hollywood to Heaven: The Lost and Saved Films of the Ormond Family? Once more the company has salvaged fragments created on the far fringes of the industry, but while Murphy’s work suggests a clear identity – an outsider auteur – the films of Ron Ormond, his wife June and son Tim, at least initially, lack a clear personal signature, dictated rather by a desire to cash in on exploitable material. But this changed in the late ’60s with an abrupt swerve into a niche which seems all the more bizarre in light of the earlier movies. As a whole, it’s difficult to get your head around this family’s career trajectory.

The Indicator set is one component of a larger project, made in collaboration with filmmaker Nicholas Winding Refn and author Jimmy McDonough. McDonough, who wrote the superb biography of Andy Milligan, The Ghastly One, spent decades researching and completing The Exotic Ones, his book about the Ormonds published by FAB Press to coincide with the disk release, with both book and Blu-ray set “presented by” Refn[1]. I’m not sure when I’ll get around to tackling the book as it’s a massive, slip-cased hardcover weighing about ten pounds.

Ron and June met on the vaudeville circuit, where June was the more experienced performer, having been on stage since childhood, and they began what was apparently a fond but tempestuous marriage which lasted four-and-a-half decades until his death in 1981. After years in vaudeville, Ron and June made the switch to movies, starting with a slate of shoestring westerns, mostly starring B-movie cowboy Lash LaRue. Shooting quickly for peanuts, with no studio backing, the couple produced four in 1948, eight more in 1949, and another seven in 1950 before Ron ended the year with his first directorial effort, King of the Bullwhip (1950).

The exploitation movies

The set doesn’t include even a sample of this genre – and I can’t say I’m entirely sorry as the poverty row western is one of the most generic of genres (there seem to be quite a few of the Ormonds’ up on YouTube, so they’re available if you’re interested) – beginning instead with a jungle adventure shot in 1951, but not released until 1955. While Untamed Mistress is as cheap and perfunctory as any such drive-in filler of the period, it nonetheless manages to provide some surprises. Unlike similar studio-made movies, it contains a startling amount of nudity and an overt suggestion of bestiality. The Ormonds apparently understood that as outsiders they had to push the envelope in order to maintain a foothold in the crowded exploitation market.

Velda (Jacqueline Fontaine) was raised in the jungle by a tribe of gorillas and has a greater affinity with the great apes than her fellow humans. “Rescued” by a Maharajah (Byron Keith) who had killed her ape lover, she remains wild and untamed, but that hasn’t stopped hunter Jack (John Martin) from falling in love with her. On his deathbed, the Maharajah urges Jack and his buddy Arthur (Allan Nixon) to take her back to her “people” and they set off into the wilds.

Along the way, they encounter African tribes engaged in various ceremonies – documentary footage which includes a lot of bare native breasts which will provide some kind of “educational justification” for later displays of staged nudity as the party reach gorilla territory and witness marriage ceremonies between ape-suited stuntmen and almost-naked African-American extras. This must have been eye-opening for drive-in audiences in the South, who not only got an eyeful of bare breasts, but were also presented with the spectacle of inter-species miscegenation combined with throw-away comments about evolution. As the narrator asks at one point, “Could natural selection influence the mating instinct of a girl who was brought up half-human, half-gorilla?”

Less exotic, but still touching on a taboo subject, Please Don’t Touch Me (1959, released 1963) is about a woman who is unable to have sex with her husband Bill (Larry Wallace). Although he is patient, this is obviously causing a strain on their marriage and Vicky (Viki Caron) agrees to see a psychiatrist – played by a concerned Lash LaRue – who realizes that the problem runs deep and brings in a hypnotist (Ormond McGill) to uncover the source of the problem.

It all stems from an incident when Vicky was fifteen; strolling in a park, she was attacked by a man, losing consciousness and coming to later only to be told by her mother that she had been raped. There’s some ambiguity about what really happened and further digging reveals that the real problem is Mom (Ruth Blair), a controlling and possessive woman who despises men and has instilled a deep fear and distrust in her daughter which has soured her relationship with Bill. Once all this is untangled, Vicky is able to start over with Bill, while the psychiatrist gets to work on Mom’s neurosis.

Please Don’t Touch Me is something of a throwback to 1930s exploitation, using a veneer of medical science to justify showing (or at least talking about) subjects forbidden by the Production Code (a line that goes back to movies like Dwain Esper’s Maniac [1934]). This scientific fakery also provides an excuse for some mondo-style “documentary” material about the history and practice of hypnotism going back to Franz Mesmer (played by Ron Ormond himself), with someone having a needle shoved through his arm, a fakir lying on a bed of nails, and an illustration of a man with a 103-pound scrotal tumour. All very edifying!

White Lightnin’ Road (1964, released 1967) is a more conventional drive-in movie about rivalry on the stock-car racing circuit, running bootleg liquor in fast cars, jail time and redemption, with a touch of romance. A cut-rate version of a mainstream sub-genre stretching from movies like Arthur Ripley’s Thunder Road (1958) to Joseph Sargent’s White Lightning and Lamont Johnson’s The Last American Hero (both 1973), the movie is perfunctory as drama, but it benefits from dynamically-filmed racing action (and highway chases), with quite a lot of documentary footage of on-track crashes. It’s notable for the screen debut of son Tim Ormond as the hero’s adolescent sidekick, but perhaps most importantly post-production landed the Ormonds in Nashville, which became their base for the rest of their filmmaking careers.

That move also planted them firmly in the soil of “hicksploitation”, movies set in the rural South with casts of country folk and plenty of country music. Forty Acre Feud (1965) might have served as the inspiration for the long-running television show Hee-Haw (1969-97) with its cornpone humour, roster of country stars and variety-show format. A paper-thin excuse for a string of performances is provided by electoral redistricting which has created a tiny new district in need of a state representative. Constantly bickering rivals Pa Culpepper (Bob Corley) and Uncle Foxey Calhoun (Claude Casey) both decide to run, the election coinciding with a local musical jamboree.

The jamboree quickly pushes the “plot” aside and we get performances from George Jones, Ray Price, Bill Anderson, Loretta Lynn, Roy Drusky, Skeeter Davis, The Willis Brothers and Hugh X. Lewis. Not to mention Ferlin Husky who also plays Simon Crumb who works at the local general store and Del Reeves who plays Pa Culpepper’s son, with Minnie Pearl (a perennial on Hee-Haw) as his Ma. Forty Acre Feud has little to offer as a movie, but it stands as an interesting record of a particular style of country music.

Girl From Tobacco Row (1966, released 1967) hints at the radical change of direction the Ormonds would be taking a few years later with an overt emphasis on the idea of atonement and redemption, and the constant preaching of Tex Ritter (prolific actor and singer, best-known for the theme song for High Noon [1952]) as Reverend E.F. Bolton, a stern fundamentalist who’s determined to keep his kids on the straight and narrow. He has a chance to display God’s grace when his son Tim (Tim Ormond) befriends escaped convict “Snake” Richards (Earl “Snake” Richards), who is attracted to the Reverend’s daughter Rita (Rita Faye), who sings like an Angel but barely speaks because of a stutter. Snake’s attempts to go straight are threatened by the Reverend’s other daughter, Nadine (Rachel Romen), who’s pretty loose despite being engaged to local sheriff Tom (Gordon Terry).

Snake has found his way to the Boltons’ because his old chain gang buddy, who died during their escape, told him about a stash of stolen cash hidden at the family farm. The family’s generosity creates a bit of inner conflict, but a bigger problem is some gangsters (led by Ron Ormond himself) who are also after the loot, leading to a climactic showdown and a final scene in which the dying Snake makes it to the Reverend’s church just in time to accept Jesus as his saviour before he dies.

Going chronologically, the significance of this isn’t immediately apparent as Ormond’s final all-out exploitation movie is rife with sleaze and touches of gore. Giving its title to McDonough’s book, The Exotic Ones (1968) sets the scene with a colourful montage of New Orleans imagery – Bourbon Street and Mardi Gras – before settling in at the strip joint where owner Nemo (Ron Ormond himself) is auditioning new dancers. No one really catches his fancy as none have the exotic flair of headliner Titania (Georgette Dante), who uses fire in her act (including flaming pasties). What he needs is something new and exciting and news reports of a monster killing people out in the swamp suggest a new attraction.

Nemo hires some guys to go catch the beast and they in turn hire local kid Timmy (Tim Ormond) to lead them to the monster’s lair. The job proves more difficult than anticipated as the Swamp Thing (Sleepy LaBeef) rips off one man’s arm and beats him to death with it. But in the end they manage to subdue the troglodyte and get him back to the strip club where he’s incorporated into a beauty-and-the-beast act with hints of King Kong. Naturally he eventually escapes and wreaks havoc. But before then, we’ve had seedy attractions like gangsters leaning on someone who owes them money and forcing him to drink the foul contents of a spitoon, plus the cheerful distraction of June Ormond herself, as the strippers’ den mother, recalling her old vaudeville days by performing a fan dance.

I must admit to feeling a bit disappointed by The Exotic Ones, having expected it to be the set’s highlight. The elements are all there, but they don’t quite gel into a satisfactory whole for me. I might be reading too much into it, but I got the impression Ormond’s heart wasn’t really in it any more. Certainly, the business was changing and exploitation was leaning increasingly towards graphic violence and more explicit sex, and the family wasn’t interested in heading in that direction. The grounds for a major change had been prepared in 1967 when the family survived the crash of their small private plane, with Ron attributing that survival to the intervention of God.

The movies the Ormond family made throughout the ’50s and ’60s, at least those preserved in the set, don’t really hold much intrinsic interest – at least not for me. They are much like so many other fringe productions made for the express purpose of recouping their investment and hopefully making a little profit on the Southern drive-in circuit, but they don’t display much in the way of an authorial signature. Even the films of William Grefé and Bill Rebane, not to mention someone like Andy Milligan, display a personal creative drive which is not apparent in Ron Ormond’s movies. As such, the first two disks in the set are mostly just interesting for what they say about the lower rungs of exploitation. Much more interesting is the abrupt change of course represented by the final two disks.

*

The religious movies

Disgusted with the direction the business was taking towards the end of the decade, and questioning the kind of work they had been producing, the Ormonds found a new sense of purpose when they connected with fundamentalist preacher Estus Pirkle, discovering an alternative venue for the distribution of their work – beginning with their first movie after The Exotic Ones, their films would be seen exclusively on the Christian circuit, screened in churches and community halls in conjunction with ongoing drives to get people to commit to Jesus and be born again.

Admittedly, I’m very much not the intended audience for these movies. I don’t have a religious bone in my body, having been born into an agnostic (if not outright atheist) family. I find the idea of a personal god which takes a minute, voyeuristic interest in the doings of billions of individuals to be ridiculous on its face; and the idea that this god, endlessly touted as the exemplar of love and justice, would condemn the majority of those individuals to an eternity of unbearable pain for what amount to petty infractions of arbitrary rules is simply appalling. If such a god did actually exist, it would be a psychotic monster and any willing submission to its absurd demands is incomprehensible to me. I mention this in order to make clear the perspective from which I viewed the religious movies which occupied the rest of the Ormonds’ filmmaking practice.

Apart from a commitment made to God when faced with imminent death in the family plane, the new direction came when the Ormonds were approached by Mississippi pastor Pirkle, who came looking for help in getting his message across to a wider audience. That message, which he had been preaching around the country, was a mixture of End Times prophecy and rabid anti-communism. Pirkle saw America going straight to Hell unless the populace could be roused to swear allegiance to Jesus. Ron was all-in and persuaded the pastor to deliver his sermon directly to camera while he surrounded it with some of the most fear-mongering Right-wing propaganda seen on American screens since the early ’50s … with the added spice of gore, the slaughter of children and the rape of good Christian women.

In recent decades, Christian filmmaking has become big business, attracting an audience of believers with a mix of sentimentality and tendentious lies about “the enemy” – that would be a secular society which rejects the idea of a theocratic dictatorship determined to impose its rules on a diverse population. But apart from the prolific sub-genre of Rapture fantasies, most of these movies try to convince the already-convinced with ridiculously skewed arguments that they are right (like the God’s Not Dead series, begun in 2014 and still going). But in 1971, Ron wasn’t having any of that disingenuous polish; If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? hammers Pirkle’s message home with all the techniques the Ormonds had honed in two decades of exploitation filmmaking. (The title, taken from Pirkle’s sermon, is apparently a tortured reference to a passage in the book of Jeremiah: “If you have raced with men on foot and they have worn you out, how can you compete with horses?”)

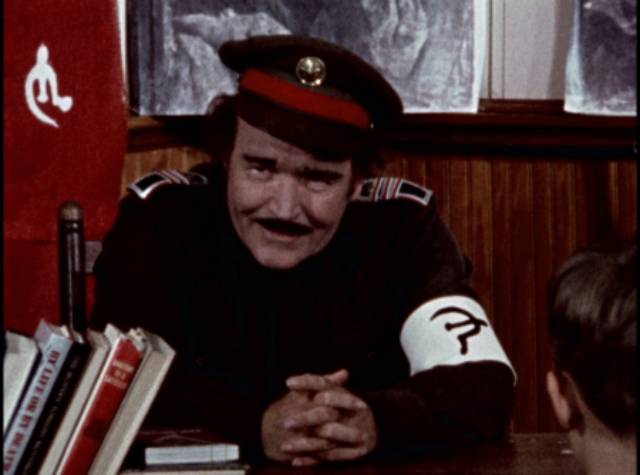

Leering commissars indoctrinate school children, they massacre Christians gathering in secret to worship their Lord, they get drunk and rape wives in front of their husbands… The camera lingers over piles of bloody bodies as Pirkle urgently gives his message that the faithful are a threatened minority who must renew their commitment to God and stand against the monstrous political forces working to pave the way for Satan’s kingdom on Earth.

Pirkle is a fascinating presence, his fanaticism couched in an aura of warmth and urgent concern, and the message becomes more violent as you (at least I) become aware that he’s a master manipulator, the quintessential sociopathic cult leader with an ability to convince his followers that he’s only offering what they’ve always longed for, that sense of belonging to the chosen few, excluding all who have different opinions; in fact, those who don’t share these beliefs are homicidal monsters, thus implicitly justifying Christians taking control of society by force.

Integral to the message is an overwhelming sense of fear and hatred, which is paradoxically couched in terms of “God’s love and mercy”. If you don’t submit whole-heartedly to the demands of this God, you will suffer – first at the hands of Earthly monsters like the Commies, then for Eternity in God’s specially designed prison. The need to terrify the audience into obedience is surely a tell-tale sign that the superficial gloss of love and mercy is a con, a point made all the more apparent in the second of the three collaborations between the Ormonds and the preacher.

The Burning Hell (1974) is another sermon, this one grimly unforgiving; the majority of people will go to Hell when they die because they choose Earthly pleasures over obedience to God. The sermon rails against such horrors as Saturday morning cartoons and dancing. The dramatized story woven around this is pretty grim. Tim Ormond plays a young, wayward Christian more interested in hanging out with his reckless biker buddy than attending church. But he’s thrown into confusion when that buddy skids off the road and is decapitated. Staggering into church and interrupting the pastor’s spiel, he’s told that without doubt his friend is right now burning in agonizing fires among lost souls and malicious demons. And to prove it, we go right there to see those souls in torment, their flesh charred, driven mad by hopelessness. Yes, for the sin of taking a bike ride on a Sunday instead of listening to Pirkle preach, Tim’s friend is doomed to an Eternity of agony. No wonder the teary-eyed wayward Christian heads for the altar and kneels to accept Jesus as his personal saviour as Pirkle turns directly to camera and urgently asks the movie’s audience if they too won’t come forward to declare for Jesus?

Apparently this cinematic altar call, screened in churches, actually would inspire members of the congregation to come forward. Fear is a great motivator … and a far more effective tool than vapid reassurance. The third and final collaboration before the Ormond-Pirkle relationship soured attempts to show the alternative to all that horror, but the task is beyond Ron and apparently also beyond the preacher himself. The Believer’s Heaven (1977) utterly fails to create an appealing image of the titular destination for faithful Christians. It’s all white robes and just hanging out with others who believe exactly the same as you. Sure, there are streets paved with gold, and vast mansions to live in, and picnics on the shores of the River of Life, with an occasional friendly wave from the white-bearded old man himself … but it seems utterly anodyne and numbingly boring. And what gives with all the symbols of great wealth? Why would anyone in Heaven need money?

This was the most expensive of these movies, with location shooting in Israel, but it was less well-received and the Ormonds and Pirkle parted ways. As Pirkle’s son Greg pointed out, “When you preach about Heaven, people do not respond to that as much as they do when you preach about Hell. People aren’t as pulled by wanting to be somewhere good as they are wanting to be pushed from somewhere that’s bad.” That sums up succinctly the big problem with the evangelist project; it’s rooted in fear, scaring people into compliance.

The underlying ugliness is fully on display in the movie the Ormonds made between Pirkle’s Hell and Heaven, this time with an assortment of other preachers (including Jerry Falwell). The Grim Reaper (1976) gives Tim Ormond his biggest role yet as a budding young preacher troubled by his father’s and older brother’s disdain for religion. Despite the pleas of Tim and his mother, neither man is interested in going to church, with brother Frankie just wanting to be a stock car racer. His refrain is “I’ll believe when dad does.” And even as he lies dying after a crash, with Tim and mom pleading with him to repent, he says it again and dad just can’t bring himself to accept God – so Frankie dies and goes straight to Hell.

As in the other movies, the sermon and drama are interspersed with a few biblical re-enactments, this time with June Ormond showing up in heavy make-up as the Witch of Endor. These sequences in all the movies are inserted in an attempt to instill the overwrought narratives with some authority, a technique going at least as far back as Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1926) – after all, if the Bible is the inerrant word of God then quoting it legitimizes whatever point you’re trying to make about our fallen world. Needless to say, it all leads to the inevitable climax with dad making that walk to the altar and declaring his fealty to Christ amidst much rejoicing as everyone seems to forget that Frankie is still burning in hellfire with no possibility of reprieve – ironically sent there by the influence of the man now so happily saved.

After parting ways with Pirkle, the Ormonds continued with the Christian proselytizing, but incorporated it into a kind of call-back to the hicksploitation years with 39 Stripes (1979), a biopic about a man named Ed Martin (played inevitably by Tim), who’s condemned to a chain gang in the ’40s and resists the prison authorities, garnering harsh punishments – the title refers to whipping, the number of lashes derived from a biblical rule which says that since forty lashes will kill, you should stop at thirty-nine – and the enmity of fellow prisoner Dan (Craig Cortney), who beats him up and eventually sets out to kill him. Meanwhile, his sister’s friend at Bible college, Alfreda (Nancy Harper), keeps writing to Ed in hopes of making him see the light … and eventually he asks the warden for a Bible, reads it diligently (in fact keeps it his back pocket at all times), and stops fighting against the authorities. In fact, when Dan savagely beats him, he takes it meekly because of the admonition to “turn the other cheek”. His piety impresses the warden, but inflames Dan’s animosity.

One Sunday, when the preacher can’t make it to the prison, the warden asks Ed to preach the sermon. He humbly agrees and serves up some downhome wisdom which has even old, hardened cons teary-eyed, and at the climax Dan, who has come armed intending to kill him, instead kneels at the altar and accepts Jesus as his saviour. The real Ed Martin went on to found a prison ministry. After the violence and horror of the sermon movies, 39 Stripes seems rather tame and conventional; but like those earlier movies it’s obviously preaching to the converted, reassuring its church audience that what they believe is indeed the truth. To an outsider, the sudden conversion of unbelievers in these films is dramatically and psychologically unconvincing, which seems to be a problem with Christian cinema in general – in order to believe you have to already believe; there are no convincing arguments presented to sway any actual unbelievers. It’s an entirely self-contained system, designed to reinforce the target audience’s shared identity.

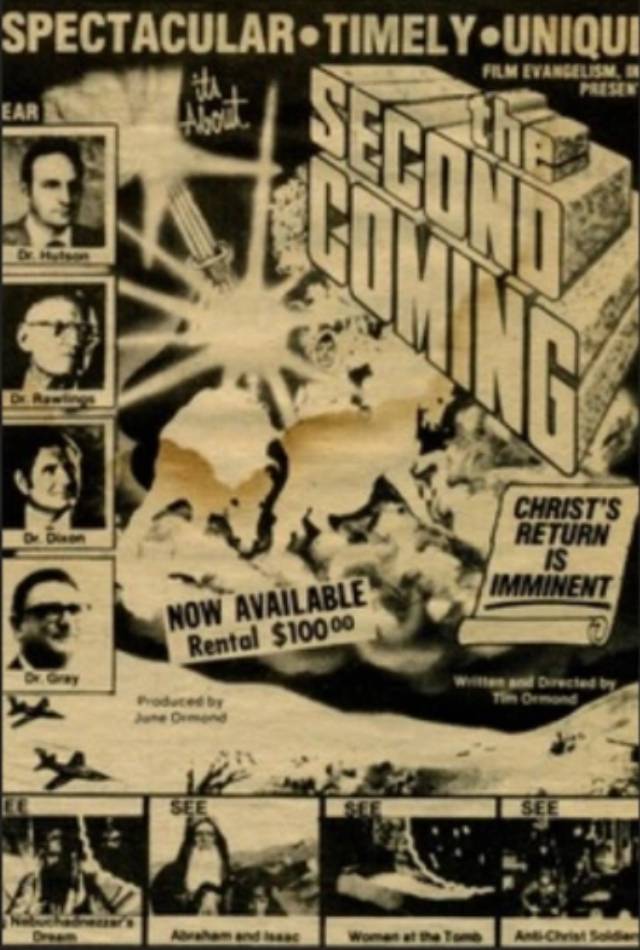

Tame inspiration again gave way to fear-mongering in the family’s next project, but Ron died during pre-production and Tim, who had co-written the script with his father, took over as director on It’s About the Second Coming (1980) – not the first Rapture movie, perhaps, but it hits all the major notes of the genre. Once again mixing sermon, biblical re-enactments and elements of narrative, Second Coming throws in some sci-fi with its glimpses of a near future after true believers have been Raptured, leaving the unlucky rest of humanity to deal with the Antichrist in the form of a One World government which demands that everyone get the mark of the beast (“666” tattooed on forehead or right hand), which is required in order to take part in any commercial transactions.

Those who refuse the mark are hunted down and summarily executed (even young children, of course). This presents a paradox endemic to the genre: if all good Christians have been taken up, how is it that a lot of Christians remain on Earth to be persecuted? If these remnants have a strong enough belief to refuse the mark and thus willingly face a martyr’s death, why weren’t they whisked off to Heaven in the first place? The not-so-subtle implication is that there are right and wrong ways to believe and only “our way” can save you. As in the bigger-budget versions that followed, it’s all an excuse to preach against the evils of that communistic One World government and comfort true believers that, despite the power they actually wield in (American) society, they are indeed a persecuted minority justified in using their political influence to impose their beliefs on everyone else.

Tim manages some effective low-budget, post-apocalypse moments as the forces of the government use tracking devices to hunt down those without the mark, cutting down the hated Christians with their ray guns. But the sci-fi elements seem to move us farther away from the hellfire exhortations of the earlier movies and expose all the biblical dogma as the nonsense fantasy it is. In all these movies (and Christian cinema in general) everything ultimately rests on a mere assertion that these beliefs are true because “my holy book says so.”

This message reaches its threadbare conclusion in the last of the Ormonds’ religious tracts, The Sacred Symbol (1984), written and directed by Tim, who cobbles together some new material with bits and pieces scavenged from the earlier movies. After a biblical prologue in which a pair of believers carve a fish symbol into a bunch of rocks only to be spotted by some hostile neighbours who show up to stone them to death, we meet a young couple who, at the insistence of the man, skip church to go hear a lecture at the explorers’ club. World-roaming John Harvey (John Calvert) shows a bunch of stock documentary footage of various ritual practices and sacred sites from around the world, all this heathen stuff making members of the audience uncomfortable because they sense the work of the devil. But he reassures them that these foreigners are merely misguided because they haven’t yet heard the word about Jesus (implausible to say the least, but there has to be some reason other cultures cling to their own beliefs). The lecture ends with him bringing out a small box in which, he tells them, is something he found in the Holy Land … a rock in which a believer had carved a fish, symbol of Christ, two-thousand years ago. This, he declares, is irrefutable proof that Christians have the one, true god, unlike all those poor benighted heathens.

Yes, the mystical beliefs of other cultures are misguided delusions, the amazing spectacle of Angkor Wat a sad monument to error, when right here in this small, hand-carved stone we have absolute proof that Christianity is the real deal. Here the Ormonds’ audacious mix of exploitation and religiosity limps to an anticlimactic conclusion, a voice pleading from deep inside the cult in the vain hope that someone, anyone on the outside might be persuaded, but in the end merely revealing just how unconvincing their beliefs actually are.

From Hollywood to Heaven is an odd collection and I can’t say that I particularly enjoyed making my way through it – few of the films it contains would have held much interest for me on their own; what’s fascinating is the strange, unexpected juxtaposition of the cheap drive-in exploitation movies from the family’s first two decades in the business and the over-emphatic Bible-thumping of the next decade-and-a-half, which doesn’t discard the exploitation sensibility, but rather grafts it on to a full-throated caricature of religious piety. American puritanical fundamentalism, apparently, couldn’t exist without a wallowing in sin. This strangely conflicted perspective on the world blossomed into big business in ensuing decades, reaching its apotheosis in Mel Gibson’s horrific paean to the ecstasy of torture and suffering in The Passion of the Christ (2004).

*

The extras

Beyond the narrative arc of exploitation to religiosity, the set offers some interesting sidebars, beginning with a brief foray into ’50s UFO mania in the form of a fifty-minute “documentary” called Edge of Tomorrow (ca. 1961) about supposed close encounters in which Reinhold Schmidt was taken aboard an alien spacecraft by polite space people dressed in suits (the crew includes both male and female, though that doesn’t mean this advanced civilization isn’t just as sexist as our own). It’s all a bit dull and even less convincing than Ed Wood Jr.’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957).

After The Sacred Symbol, Tim made several documentaries on video, beginning with A Tribute to Houdini (1987), which shows magician John Calvert (who had narrated Second Coming and played the explorer in The Sacred Symbol) recreating some of Houdini’s illusions, then settles down to record his stage performance. Apparently considered the best illusionist since Houdini, his tricks seem unimpressive as filmed by Tim and the show is rather boring.

This was followed by Lash LaRue: A Man and His Memories (1992), a feature-length interview with the former western star in which he reminisces about his career (complete with numerous clips from the Ormond-produced westerns) and recites some of his own poetry. Towards the end, a reference to June Ormond, who produced many of his movies, brings an abrupt twenty-minute diversion into an interview with Tim’s octogenarian mother, who does some reminiscing of her own about her early career in vaudeville and comedy shorts, displaying a charming screen presence (there’s a funny bit in which she befuddles Bob Hope).

In June Carr: The Virtual Vaudevillian (1997), she takes centre stage. This short portrait and tribute to Tim’s mother allows her to recreate a string of corny vaudeville skits as she again reminisces about that long career and her work as a producer. Still lively in her eighties, her presence in these extras rather overshadows the movies in the set; here’s a vivid personality which didn’t make itself visible in the family’s movies.

Forgotten Memories (also 1997) is a short drama starring June as a widow who is visited one stormy night by a woman whose car has broken down. This visitor may be imaginary, or perhaps have some supernatural quality, but her presence prompts memories of the widow’s life, which not surprisingly reflects June’s own life.

There is also some behind-the-scenes footage of Forgotten Memories, plus five commentaries – on Please Don’t Touch Me (McDonough), The Exotic Ones (Georgette Dante and McDonough), If Footmen Tire You (Pirkle’s son Greg and documentarian Brian Rosenquist), The Burning Hell (Tim Ormond, McDonough and restorationist Peter Conheim) and It’s About the Second Coming (Tim and McDonough) – and an audio recording of a one-hour Estus Pirkle sermon from 1970.

*

Having watched everything in the Indicator set, I’m still interested in reading McDonough’s book about the Ormonds … but I can’t imagine that, like his earlier The Ghastly One, it will alter my opinion of the movies themselves. This Andy Milligan biography illuminated the films he made, but I don’t think there are any secrets to be unearthed in either the early exploitation movies of the Ormonds, or the later religious ones. In this case, it seems that the family themselves are probably more interesting than the work they produced.

_________________________________________________

(1.) Refn is becoming much more interesting for these acts of cinematic archaeology than as a director in his own right; he provided the impetus for the BFI to restore Milligan’s Nightbirds [1968] a decade ago, and was behind the revised edition of The Ghastly One published by FAB in 2020, as well as The Art of Seeing, a massive volume of exploitation posters from his own collection published by FAB in 2015. (return)

Comments