Another mixed bag …

Maybe it’s because life as we knew it is on hold right now, but I keep finding myself going back to the movies of the 1960s through ’80s, the period when I formed my tastes and opinions in their most concentrated form. Although those tastes and opinions were largely rooted in more serious and complex films – I’ve mentioned before that my real awakening came in the summer of 1973 with four particular movies seen in quick succession: Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, Terence Mallick’s Badlands, Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now and James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue, all rooted in recognizable genres but pushing those genres beyond their usual limits – these days I’m feeling drawn to more modest movies, and all too often trashier ones, from the same time frame. Guess I’m getting lazier as I get older and don’t feel like being challenged…

I’ve recently revisited a couple of movies I actually saw back when they had their theatrical release, a couple more which I knew about but had never seen … and a couple which hadn’t even been on my radar, though one was by a director whose work I’m pretty familiar with.

Conquest (Lucio Fulci, 1983)

Lucio Fulci has grown in my estimation over the years. Looking back over my notes, I know that I saw at least two of his movies in their original theatrical runs – Zombie and City of the Living Dead – and had extremely low opinions of them: crude, absurd rip-offs of better movies and notable mostly for the graphic extremes of their horror elements. I’m a fan of both now – while Fulci has chronic pacing issues (his characters too often stand transfixed and just watch as really slow-moving threats approach them), his visual imagination is really strong, the horror laced with almost poetically surreal moments (the ending of The Beyond was a major game-changer for me, stirring me to revisit the other films and look at them with fresh eyes).

But horror turned out to be just one aspect of his work, limited to a surprisingly brief period from 1979 to the mid-’80s, then petering out with some really cheap productions as his career faded. I haven’t seen much of his early work, when he was pumping out comedies (and don’t really have any interest in seeking them out), but his spaghetti westerns are passable representatives of the genre, and his gialli are up there with the best, particularly his masterpiece Don’t Torture a Duckling and, problematic as it might be, The New York Ripper. And while he was transitioning out of comedy to the films he’s now best known for, he made the historical drama Beatrice Cenci, which was one of his finest films.

Like most Italian exploitation filmmakers of the time, Fulci tried his hand at pretty much every genre, though he wasn’t always well-suited to what he did. Although I have a friend who disagrees, I’d say his weakest work in the mid-’80s were a pair of fantasies, one futuristic, the other mythic. The New Gladiators (1984) is a cheesy mix of Rollerball, The Running Man and Death Race which stretches its budget to breaking point but still can’t quite manage to make its action scenes exciting.

Conquest (1983), which I just watched for the first time, is one of countless Italian movies which tried to update the old sword-and-sandal epics of the ’50s and ’60s in the wake of the international success of John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian (1982). But Fulci ditches the visceral he-man heroics of Conan in favour of something else … though it’s hard to say exactly what that is. Ilias (Andrea Occhipinti) is sent off by the gods(?) on a rite-of-manhood quest, armed with a magic bow whose arrows are made of light. He wanders a fairly empty landscape where the peasants are preyed upon by an army (well, more of a squad) of dog-headed soldiers working for the sorceress Ocron (Sabrina Sellers), a mostly-naked meanie whose head is hidden by a gold mask. Ocron has a taste for sucking out the brains of anyone her dog-soldiers bring her, and becomes obsessed with getting that magic bow.

During one fight, Ilias is aided by muscleman Mace (Jorge Rivero) and the pair team up to defeat Ocron. There’s some running around, some fights, some brain-sucking and a final ridding the land of Ocron and her minions. It all amounts to weightless silliness which eventually becomes an eyestrain because the whole thing is shot through a fog filter which makes everything vague and gauzy. Obviously meant to evoke a sense of timelessness (and placelessness), it mostly makes you want to take a wet cloth and keep wiping your TV screen so you can actually see the image.

Code Red’s transfer does what it can with this challenge to the limits of digital technology, but I doubt the movie would be any better if you could see it all clearly. The packaging is really nice though, with cover art which promises something much more epic, plus there’s a brief jokey interview with Rivero and a commentary from genre specialists Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson (which I haven’t listened to).

*

Fiend/Blood Massacre (Don Dohler, 1980/1991)

After watching Don Dohler’s amateurishly amusing Nightbeast, I figured I’d take a look at some of his other movies. His first feature, The Alien Factor (1978), proved to be tedious to a point where it was all but unwatchable, but Massacre Video’s Blu-ray double feature of Fiend and Blood Massacre (the latter a hidden special feature) turned out to be quite entertaining. Which is not to say that they’re good movies, just that like Nightbeast they have a kind of do-it-yourself charm.

In Fiend (1980), Dohler’s second feature, a malevolent spirit takes up residence in a body buried in a small town churchyard and moves to the suburbs, where it needs to suck the life force from someone at regular intervals in order to keep the body from rotting. As Eric Longfellow (Don Leifert), the spirit sets up a music school run by meek Dennis Frye (George Stover), also giving private lessons to special students in his basement. He drives his cul-de-sac neighbour Gary Kender (Richard Nelson) crazy with all the loud classical music, and Kender goes on a crusade to prove that Longfellow must be behind the recent string of mysterious deaths.

Strangely, Gary is so obnoxious that viewer sympathy ends up being with the soul-sucking demon as it kills various women walking alone at night and even a young girl in a gully behind the houses in the cul-de-sac. Meanwhile Gary’s wife Marsha (Elaine White) is starting a filmmaking project with a local Scout troop and buys a stack of copies of Dohler’s how-to book Movie Magic to give to the kids (getting in a fairly lengthy plug about how great the book is). While Fiend is rather dull, it has an oddly hypnotic quality which keeps you watching.

Blood Massacre (1991) is a bit livelier and is the most entertaining of the four Dohler features I’ve seen so far. No longer meek, George Stover turns up as crazed Vietnam vet Rizzo, a guy who wanders into a small town bar, insults everyone, and later kills the waitress with his knife. He turns out to be a member of a seriously incompetent gang of robbers who knock over a busy video rental store, killing some people and netting a very small take considering the violent effort involved.

On the run from the cops, the gang hide out at a remote farm where they hold the Parker family hostage … at least, that’s what they think they’re doing until it becomes clear that the Parkers have modelled themselves on a certain famous Texas family. They’re in the habit of renting out rooms to students whom they kill and eat, turning them into stew that they sell at local events. Even the psychotic Rizzo is no match for the cheerful cannibals…

Needless to say, the video quality is pretty rough for both movies. There’s a commentary on Fiend, some archival interview clips, a blooper reel and four of Dohler’s shorts, mostly made when he was in his teens. Blood Massacre isn’t even mentioned on the packaging or menus and has to be found by playing around with the direction arrows on your remote.

*

The two films I revisited reflect very different interactions of time and memory. One I liked back when I first saw it and I find it holds up well; the other I didn’t think much of back then, but found myself responding to far more positively this time.

Fear No Evil (Frank LaLoggia, 1981)

The former is Frank LaLoggia’s first feature, Fear No Evil (1981). I recently wrote about LaLoggia’s second feature, Lady in White (1988), which has risen in my estimation since I first saw it – Fear No Evil pretty much conformed to my memory, though. Made when slashers were beginning to dominate the horror field, it had a slight throw-back quality, recalling the flood of mid-’70s, post-Exorcist demonic horrors. Once again, Satan is about to be reborn on Earth, ushering in the final stages of a cosmic conflict between Good and Evil. But what could have been hackneyed is given freshness by LaLoggia’s treatment.

Like Lady in White, Fear No Evil has the qualities which often come from a regional filmmaker working outside the mainstream with limited resources bolstered by commitment and ambition. A distinguishing characteristic of both films is the obvious sincerity of the director – these aren’t tossed off efforts made as a quick cash-in on a popular trend (as were so many of the ’80s slashers), but rather (at the risk of sounding naive) made with heart, with writer-director LaLoggia investing genuine feeling in his characters.

The protagonist is Andrew Williams (Stefan Arngrim), a misfit teen approaching his eighteenth birthday. The butt of mocking contempt from his high school classmates, he’s full of Goth angst – as it turns out, more justified than usual, because he’s beginning to awaken to the fact that he’s Satan incarnate … which explains all manner of creepy occurrences going back to his baptism when the water in the font turned to roiling blood. His parents have always been afraid of him and several mysterious figures have lingered at the edges of his life. These turn out to be three Archangels incarnated in human form to prevent Andrew’s eventual rise to power.

The final stretch of the film takes place on a small lake island where the ruins of a rich man’s unfinished castle provide great production value and plenty of atmosphere. (This is Boldt Castle, on an island in the St. Lawrence River.) As Andrew begins his rituals, the dead begin to rise and attack a bunch of kids celebrating graduation among the ruins. As in Lady in White, the final confrontation between Good and Evil involves some slightly cheesy optical pyrotechnics, but again as in the later film, LaLoggia has established narrative and character so well that it’s easy to forgive a few technical shortcomings … and once again, he shuns the common cynical nihilism of the time and allows Good, at least for the moment, to put Evil back in its subordinate place.

If I needed to compare LaLoggia to any other filmmaker to indicate his particular qualities, it would be another long-time favourite, Don Coscarelli; he too approaches horror with a paradoxically upbeat attitude, combining atmosphere and scares with a disarming charm.

Scream Factory’s Blu-ray gives the film itself a very nice presentation – in fact, a terrific upgrade from Anchor Bay’s 2003 DVD release – but omits the earlier disk’s extras, which included a LaLoggia commentary and twenty minutes of behind-the-scenes material. The new extras, though, are quite substantial: a commentary with star Arngrim, and lengthy interviews with Arngrim (37 minutes) and special effects supervisor John Eggett (28 minutes). The absence of LaLoggia on the disk may be explained by his less than happy experience dealing with the company on their Lady in White release.

*

Rituals (Peter Carter, 1976)

The movie about which my opinion radically changed is Peter Carter’s Rituals (made in 1976, released in 1977). Back in 1977, I gave it one star, and I was genuinely puzzled when Stephen King praised it in his book about the horror genre, Danse Macabre (1981). Carter, an Englishman transplanted to Canada for most of his career, made only a handful of theatrical features, spending most of his time in episodic TV production. There were a number of reasons why Rituals disappointed me, but perhaps the biggest was that Carter had previously made a movie that I really loved. The Rowdyman (1972), written by and starring Gordon Pinsent (“There’s more to Epicurianism than a good meal.”), had been shot in Newfoundland the year before I moved away and it was not only an engaging character study, its comic tone turning unexpectedly dark in the second half, but also an evocation of the time and place I was actually living in – this was a new experience for me and I felt a real bond with the movie. (I haven’t seen it in almost fifty years and I’m nervous about watching the only copy I’ve been able to locate – a really ugly full-frame video on YouTube which appears to be taken from an old VHS tape.)

Other reasons for my initial negative opinion of Rituals were the fact that this was a low-budget Canadian retread of Deliverance and it had an unsatisfying final act which gives a lame and implausible explanation for what had been happening to the characters. The story is about a group of friends, all doctors, who get away together every year, and this year they’ve decided on a wilderness canoe trip. Once they’ve been dropped off by small plane, they have no way out until the plane returns to pick them up in a week. But the drinking, joking and bickering have already started before they even get on the plane.

The main character, Harry (Hal Holbrook, in an atypical, physically demanding role), is troubled by some of his friends’ borderline unethical practices designed to boost their income through the commodification of medical procedures. He himself continues to work at an unprofitable clinic where he heads the neurosurgery unit. A bit humourless, it’s easy to see why his moralizing bugs the others. In slasher terms (and these wilderness movies are close kin to that genre), Harry is the obvious “final girl”, the unsullied one whose purity forms an armour against the homicidal menace who will soon be stalking the group.

Like any bunch of guys turned loose far from social constraints, the men’s inner immaturity quickly emerges; they’re loud, kind of obnoxious, and seriously lacking in respect for the wilderness. It’s no surprise that some unseen entity begins to play tricks on them – first by stealing all their hiking boots while they goof about in the river. Only one of them was smart enough to bring extra shoes, so hiking is going to be a problem. Putting on his runners, D.J. (Gary Reineke) agrees to walk some twenty miles upriver to find a hydro dam marked on their map, where he hopes to get help. The next morning, coming out of their tents, the others find a dead deer ritually hung up in the camp. Okay, this doesn’t look good. Instead of staying put and waiting for help, they wrap their feet in rags and begin to follow D.J. in the canoe.

It turns out none of them are in great shape and the trek quickly becomes exhausting; the ordeal is aggravated by the unseen presence stalking them; they begin sustaining serious injuries … and soon they can’t stop attacking each other rather than working together. By the end, of course, it’s Harry against the menace and the principled doctor is reduced to a level of brute violence, forced to kill to save himself. The problems with the ending can only be addressed with spoilers – so be warned.

Their nemesis is a mentally deranged vet, hideously deformed because of incompetent army doctors who did a really bad job of patching up his wounds. He lives with his brother in a cabin near the dam (which, by the way, was decommissioned years ago, so no help there), and he targeted the group specifically because they were doctors – his crazed mind wanted revenge, so if they’d been accountants he’d have left them alone. How this madman living out in the wilderness could know that this random group dropped on the river twenty miles away were all doctors is a mystery left unexplained, so the motive for him tormenting them makes absolutely no narrative sense. This remains unsatisfying, and yet this time round, I found the movie quite gripping.

Yes, it’s still a Canadian imitation of Deliverance with an implausible ending (the script should have found a better way to trigger the conflict between the doctors and their stalker), but it actually has some real visceral power. Carter, his cast and a small crew, shot it more or less in sequence on a remote location, the actors being subjected to some gruelling challenges on the fast-moving river – and that hard-earned realism generates genuine tension which is well-played by the cast. In fact, watching their struggles seems more exhausting than Deliverance itself.

Carter makes good, and intelligent, use of the spectacular landscape – the harsh claustrophobia of the river and woods eventually gives way to a high ridge with impressive views over miles of rolling hills and forest, which ought to provide a sense of relief but actually serves to make the surviving men seem that much smaller and more isolated. He also stages some gruesome bits of business very effectively (the early morning discovery of the head of one of their friends impaled on a stick is genuinely unnerving) and the final confrontation between Harry and the “monster”, while poorly supported by the revelation of the killer’s identity, is well-staged and pretty grim as Harry doesn’t act in time to save his friend Mitzi (producer Lawrence Dane) from a particularly nasty fate. So despite certain weaknesses which could have been fixed with a rewrite of Ian Sutherland’s script, Rituals is a much more intense, and frequently satisfying, experience than I gave it credit for back in 1977. It’s definitely one of the better examples of Canadian exploitation cashing in on successful American movies.

Despite the film’s age and low-budget origins, the image on Scorpion’s Blu-ray is pretty good, with good colour rendition and detail, though print damage is certainly apparent at times. There’s a commentary and on-camera interview with producer and co-star Lawrence Dane, plus an interview with actor Robin Gammell about the gruelling shoot, all of which are carried over from an earlier Code Red DVD edition.

*

Finally, two movies I’d wanted to see for a long time, but for whatever reason hadn’t come across before their recent Blu-ray releases.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (John Hancock, 1971)

In retrospect, it’s puzzling that I’d never seen John Hancock’s first feature before. I can recall reading a review in an issue of Cinefantastique (Vol 2, No. 1), which wasn’t very positive. I just dug it out and the reasons for Fred Clarke’s negative assessment are interesting. The quality of the performances and richness of the character relationships are “demeaned” by the horror elements. The implication is that horror simply can’t support serious drama … which coming from a magazine dedicated to genre movies seems a bit short-sighted.

For me, this is a belated discovery from one of my favourite periods, when for a few years directors on the fringes were making artful, even poetic, movies which used the tools of the horror genre to do exactly what Clarke was complaining about. These movies explored themes and character in dreamlike ways, adding something which enriched what would have been less memorable if treated on a purely realistic level – that is, they expanded the genre with a degree of psychological depth and insight often missing in more routine horror movies. This was the time of Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (1973, and where’s the Blu-ray restoration of that gem?), Willard Huyck’s Messiah of Evil (also 1973), John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire (1972), Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976), Frederick R. Friedel’s Axe (1974) and other great low-budget independent horror movies.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971) fits nicely into that company with its mix of languid sunshine and creepy menace. Jessica (the strangely ethereal Zohra Lampert) is recovering from a breakdown. Along with her husband Duncan (Barton Heyman) and their friend Woody (Kevin O’Connor), they move out to the country to live in a big old house by a lake in Connecticut. Arriving in a large vintage hearse like slightly over-age hippies, they are greeted with chilly hostility by the locals. But this doesn’t seem to be just the usual rural distrust of unconventional city folk; a vague cloud hangs over the village and some of the men have bandages on their throats.

When they arrive at the house, the trio discover a woman squatting there. Emily (Mariclare Costello) explains that she thought the place was abandoned and starts to grab her stuff to leave – but the trio decide to invite her to stay. Jessica’s insecurity creates tension; she’s welcoming, but at the same time begins to sense that both Duncan and Woody are attracted to Emily. However, given her recent problems, she’s uncertain about her ability to perceive things clearly – in fact, she begins to see things that unsettle her. There’s a girl in white who seems to appear and disappear like a ghost (a young Gretchen Corbett) and a dead body by the lake which disappears by the time she’s brought the men to take a look. Swimming in the lake, a wraith-like figure rises up through the water to drag her down.

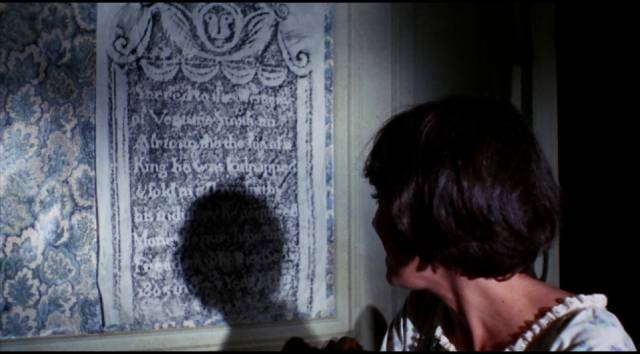

Then there’s the photo in the attic of the 19th Century family who once lived in the house; the daughter, who committed suicide, looks an awful lot like Emily. As the town gradually succumbs to what appears to be a vampire, Jessica struggles to distinguish what’s real from what may be the delusions of a fragile mind over which she has only tentative control. Everything is experienced through Jessica’s uncertain point of view and the depth of the writing and performances gives the film the richness of a 19th Century Gothic novel.

Drawing on his own experience as a stage director and on the New York theatre scene for his cast, writer-director Hancock put far more care into his characters than was typical for a low-budget genre movie, transforming this vampire tale into an affecting drama. Lampert in particular is riveting; her unusual looks and voice largely kept her out of starring roles, though she had a long movie and television career, so this film is perhaps the best showcase for her talents and she rose to the occasion with a moving, unsettling performance. The rest of the small cast provides excellent support.

If I have one quibble, it’s the title; it seems to situate the movie in a particular genre – going back to Gaslight (1940/1944) and, more recently, various “hag horror” movies starring Bette Davis and Joan Crawford – while actually belonging to a more subtle category (exemplified by Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby and The Tenant). The title is likely to mislead an unsuspecting viewer and may have hampered the film’s commercial success.

The Shout! Factory disk has a really nice, textured image, supplemented with a commentary from director Hancock and producer Bill Badalato, an interview with composer Orville Stoeber, a location featurette, and a 24-minute interview with Kim Newman which he begins by enthusiastically declaring that this is his favourite horror film.

*

Serie Noire (Alain Corneau, 1979)

I became a fan of Jim Thompson when a friend gave me a copy of The Killer Inside Me in 1983. That actually wasn’t my first encounter with Thompson’s work, having seen his contributions to Stanley Kubrick’s early films (The Killing, Paths of Glory), and more pertinently Sam Peckinpah’s adaptation of The Getaway (1972) and Bertrand Tavernier’s Coup de Torchon (1981), a brilliant adaptation of Thompson’s novel Pop. 1280 transplanted from the American Southwest to a pre-war French colony in Africa – but I wasn’t aware of Thompson himself as in those cases it was the directors’ work which had attracted me. Reading that first novel was a whole other matter; Thompson got inside his psychotic character’s mind with such twisted, nightmarish humour that I was immediately hooked … and the timing couldn’t have been better as Black Lizard was just embarking on republishing many of the novels. I bought everything I could find, and over the next few years I managed to read almost all of Thompson’s books (and a decade later, Robert Polito’s Savage Art, a terrific literary biography which confirmed my admiration for Thompson). Although working in the realm of cheap pulp paperbacks, he was often a remarkably sophisticated writer, using complex techniques to explore point of view through thoroughly unreliable narrators. His work was incredibly dark; I recommended him to other friends, and at least one of them found him too disturbing to read.

He created remarkable effects, like having the first-person protagonist of Savage Night (1953) narrate himself all the way into death. But one of his most audacious technical achievements comes in the final chapter of his 1954 novel A Hell of a Woman. There he writes two endings in alternate lines, one the sordid demise of the narrator, the other his attempt to rewrite his life into something more bearable. Finding this demanding literary technique in a pulp crime novel sold on drugstore paperback racks must have been pretty confusing for unsuspecting readers back in the 1950s … and would no doubt pose a real challenge for anyone adapting the book for the movies. In fact, a lot of the films made from Thompson’s books fail to capture their distinctive qualities because what he so often dealt with were his protagonists’ deranged inner states; more straightforward adaptations tend to revert to the pulpiness of their surface narratives – Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972), Burt Kennedy’s The Killer Inside Me (1976), Roger Donaldson’s The Getaway (1994), Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me (2010) – and what remains when the prose and the complex points of view are stripped away is merely the nastiness of the world Thompson created.

As the French recognized the value of cheap American post-war thrillers which they dubbed film noir before most American critics noticed what was going on, they also embraced the pulp fiction of writers like David Goodis, Charles Willeford, James M. Cain and, of course, Jim Thompson. These movies and books were steeped in existential crises which resonated with a society recently emerged from the grim nightmare of the Occupation. Filmmakers who drew on that pulp fiction for inspiration were inclined to treat these sordid stories of low-life and crime as a form of popular art rather than simply trashy entertainment. Francois Truffaut adapted a David Goodis novel for his second feature, Shoot the Piano Player (1960), as did Jean-Jacques Beineix for his second feature, The Moon in the Gutter (1983), and Tavernier made a masterpiece in Coup de Torchon. If further proof were needed, when Alain Corneau set out to adapt Thompson’s A Hell of a Woman, he actually chose prominent French literary experimenter Georges Perec as his co-writer.

I first heard of Corneau’s Serie Noire (1979) in 1984; it was mentioned on the back cover of Black Lizard’s paperback reprint of A Hell of a Woman. Naturally, I wondered how Corneau would have handled that dual-narrative ending … and now that I’ve finally seen the film, I’m not surprised that he avoided the challenge altogether (just as Walter Hill’s script for Peckinpah’s The Getaway totally dropped the final, and most interesting, part of that novel). Which is not to say that Corneau stripped the source to its narrative basics; Serie Noire stays very close to its protagonist’s claustrophobic perspective, giving the viewer a feverishly distorted experience which is often very uncomfortable.

Having only watched the film once so far, I confess to some ambivalence. Like Tavernier, Corneau shows that there’s some psychological essence in Thompson’s work which, while on the page, seems specifically tied to a regional American milieu actually translates effectively to an entirely different environment and culture. Here, that environment is the bleak outskirts of Paris (specifically Creteil, to the southeast of the city), an area where new housing developments abut sprawling, mud-choked wastelands; although it’s an area in the process of development, it gives off an atmosphere of collapse and decay.

We first meet Franck Poupart (Patrick Dewaere) in the middle of this wasteland as he entertains himself by pantomiming an action scene from a gangster film in his head, ducking and weaving beside his car, spinning and firing an imaginary gun – this performance segueing into a dance with an imaginary romantic partner. While the symbolism is rather obvious, it lays the groundwork for what’s to come – Franck, like Belmondo in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), has been colonized by the violent fantasies of American pop culture. In reaction to a generally hopeless existence, he has developed an exciting inner life which in turn will begin to shape his reality when chance gives him an opportunity.

A door-to-door salesman and debt collector, Franck works for a seedy boss (Bernard Blier, director Bertrand Blier’s father), who seems fairly indulgent of Franck’s eccentricities – until he discovers that Franck has been stealing from him. In tracking down a particular deadbeat, Franck visits an isolated house owned by a creepy old woman, La Tante (Jeanne Herviale), who prostitutes her underage niece Mona (Marie Trintignant), offering the girl to Franck in exchange for a nice bathrobe. Shocked to find himself in a seedy room with the naked girl, Franck finds his fantasies taking on more concrete shape; here’s a damsel in distress in need of rescuing … at least, that’s how he constructs the scene. Mona herself is rather empty-eyed and casual about the use to which the old woman puts her. She says very little and seems willing to conform to whatever other people want from her.

When Franck learns that the old woman has money stashed somewhere in the house, he forms a plan to escape his life, taking the girl with him. Given a new sense of direction (however imaginary), he drives his slovenly wife Jeanne (Myriam Boyer) away. But as his fantasy escape plan develops, his reality unravels – fired by his boss for theft, angered when Jeanne returns unexpectedly, and incapable of actually forming a workable plan for his crime – and his dream becomes a violent nightmare. People end up dead, he loses the money almost as soon as he obtains it, and he’s left in an even more hopeless limbo than the one in which he started, the grey open spaces of the first scene having closed in on a dark narrow street late at night, with nowhere to go and dead bodies nearby.

Serie Noire certainly captures the savage darkness of Jim Thompson’s fictional world, but I found myself kept from fully engaging with the film by the very thing which seems to get the most praise from critics: star Patrick Dewaere. The hyperactive quality of his performance reminded me quite a bit of some of Andrzej Zulawski’s films, in which the actors are pushed to such extremes that they become the embodiment of Brechtian alienation (particularly in L’amour Braque [1985] and Szamanka [1996]). While it’s in the nature of the story that Franck lives almost entirely in his own head, inside a fantasy construct pieced together from shabby pulp elements, that hermetic quality kept me as a viewer at a distance; this is the difference between a novel and a movie – in the former, the reader becomes trapped inside with the character, while with the latter the viewer remains outside of what is displayed on screen, an observer of rather than participant in the character’s increasingly confused decision-making. Dewaere remains to some degree closed off and unavailable to the viewer on an emotional level, turning the film into something like a clinical, analytical study of madness rather than an experience of that madness.

But maybe I’ll respond differently if I watch it again. It’s not unusual when encountering a work as stylistically distinct as this to find oneself watching with the wrong frame of mind. Every film is experienced as an interaction between what the artist has created and what the viewer brings to it … and sometimes, the viewer simply brings inappropriate expectations, particularly when those expectations have brewed for such a long time.

What isn’t in doubt is the superb image quality on Film Movement’s Blu-ray, mastered from a new 2K restoration. The darkness and gloom are rendered with impressive detail. There are also two substantial extras: a retrospective documentary from 2013 (52:31) and an archival piece from 2002 intercutting interviews with Corneau and Trintignant (30:06), both of which cover the origins of the adaptation and the experience of making the film, with a heavy emphasis on Dewaere’s performance (the troubled actor committed suicide just three years later at the age of 35).

Comments

Thank you for your positive mention of my film “Lemora”. One reason why there is no blu-ray edition as yet is because Synapse refuses to return my negative claiming they cannot find it. I have sent them a demand letter to which they have made no response.

On a brighter note I am also a fan of “Let’s Scare Jessica…” having been introduced to it through Kier-La Janisse’s amazing House of Psychotic Women book. And “Serie Noire” remains my favorite Jim Thompson adaptation. Corneau had been a jazz/music critic. For me his use of both Ellington’s “Moonlight Fiesta” at the beginning and the Melodians “Rivers of Babylon” during the seduction scene is achingly perfect.

What a nightmare! I really hope that gets resolved. I first saw Lemora on late night TV in the mid ’70s – pre-cable, the signal was not great and the fuzzy image made the film even more dreamlike. I eventually got hold of a VHS copy, which I prized, and regularly revisited it for years. So I was thrilled when Synapse released it on DVD back in 2004 … and now I learn that they’ve lost the negative! On top of that, I’ve been waiting for years for Stephen Thrower to publish volume two of Nightmare USA, which is supposed to include a chapter on your film.

I’ve also discovered a number of movies thanks to Kier-la’s book …

And I’ll definitely revisit Serie Noire … I think I just had to get past years of anticipation and preconceptions before I can see it for itself.