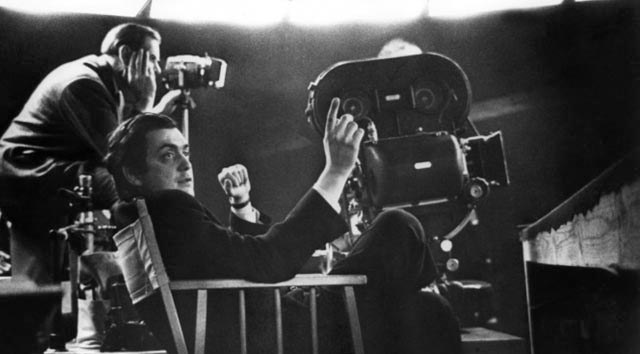

Stanley Kubrick part 1: Becoming Kubrick

My first encounter with Stanley Kubrick’s work came before I was ten years old. Sometime in the early ’60s, my parents took me to see Spartacus, probably at the Odeon in Chelmsford. For years afterwards, two things stuck with me: the gladiators training in a kind of cage and Jean Simmons, holding her baby, riding away on a chariot past endless miles of crucified slaves.

My next encounter was with 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968. I went to that several times, not for the story, not really for the big light show at the end, but mostly because it seemed to evoke so viscerally the feeling of what it must be like to be floating through the emptiness of space.

I first saw Dr Strangelove on television and thought it was one of the greatest movies I’d ever seen. Then A Clockwork Orange, first at the Odeon Leicester Square in London in 1972, then many times after that – in fact, it became one of my “most watched” movies, though now I’m not entirely sure why.

The point is, for some reason, Kubrick was for many years a key figure in my film-viewing, although for a major director his output was quite small. Perhaps that was part of the attraction; scarcity increased my sense of interest. Now, I’ve just begun to go back through his work in chronological order, starting with Criterion’s Blu-ray editions of the first three films (well, not quite first three: Fear and Desire [1953], his apprentice effort, has remained unavailable at his own insistence).

Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Seen close together, Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957) show the precocious photojournalist Stanley Kubrick transforming into the filmmaker “Stanley Kubrick”. Killer’s Kiss, the only movie he made from an original script (except, of course, the elusive Fear and Desire), offers a fairly conventional, somewhat underdeveloped story of a boxer, a dancehall girl, a mobster, budding romance and murder. Kubrick shot the film himself and it’s clearly the work of a photographer, not a dramatist. The thin storyline is merely an excuse for Kubrick to capture striking images of New York City, mostly at night, with some vivid compositions using the visual depth offered by adjacent apartments which are visible to each other across an air shaft. The pleasures of this short feature don’t lie in the rather soft noir of the script, but purely in Kubrick’s photographer’s eye. It’s an animated extension of the work we can see in Stanley Kubrick: Drama & Shadows: Photographs 1945-1950 (Phaidon: London & New York, 2005, edited by Rainer Crone).

The Killing (1956)

His next film, The Killing, was the first of eleven to be adapted from somebody else’s writing – in this case a pulp novel by Lionel White called Clean Break. There’s a transitional quality to The Killing, with that photojournalist’s eye drawn to the busy details of the racetrack which is going to be robbed, while Kubrick is beginning to flex his dramatic muscles in the narrative scenes – the plotting in squalid rooms where Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) gathers his misfit bunch of amateur criminals for the job; and most particularly in the film’s strongest scenes, the toxic marriage of George (Elisha Cook Jr) and Sherry Peatty (Marie Windsor). You can feel Kubrick’s pulse quickening as he delves into the ways in which people trapped together torture each other and make their own lives hell. The mechanics of the robbery are nicely laid out (in the famous fragmented timeline which keeps doubling back to pick up another thread of the plot at an earlier moment before everyone eventually arrives at the Big Moment), with the final resolution seeming almost too inevitable in that ironic noir way, but the director’s interest here is clearly with the sour heart of intimate relationships (you can feel some of the same tension in the transient relationship between the sniper and the black parking attendant, the crossed intentions, the stifling intrusion of another into your space, which suddenly erupts in emotional violence).

Paths of Glory (1957)

With Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick the filmmaker finally emerges in full flower. This is the artist who will be visible in virtually all the work to come; the cool, elegant visual surfaces, the long gliding tracking shots that penetrate the film’s dramatic spaces, the tendency for human figures to be dwarfed by their environment and, it seems, almost driven by some sense of individual insignificance to wreak havoc on each other. Despite a fairly widely held view that Kubrick was a coldly intellectual director, it seems to me that the chill that overshadows so much of his work has more to do with a barely contained fury at human stupidity rather than some godlike detachment. In retrospect, it’s not surprising that the first film to fully define Kubrick as an artist is a bitter story of the terrible things people do to each other in war, and further that in this case those terrible things aren’t perpetrated by one enemy on another, but rather inflicted by callous, self-serving officers on their own men. (Full Metal Jacket, made almost thirty years later, would also focus on the damage inflicted on men by their own military institutions, while Dr. Strangelove focuses on the internal madness which drives one side to destroy itself along with a supposed enemy.)

Adapted from a novel by Humphrey Cobb, which in turn was based on an actual incident which occurred in the French army during World War One, Paths of Glory presents war not so much as a violent political contest between competing nations, but rather as a function of military careerism. At the start of the movie, General George Broullard (Adolph Menjou) urges General Paul Mireau (George Macready) to send his already weakened army against an impregnable German position. Mireau says it’s impossible. Broullard suggests that a failure to act might be detrimental to Mireau’s military future. The attack is ordered, with the initially reluctant Mireau now brow-beating the realist Colonel Drax (Kirk Douglas) into undertaking what both men know is a suicidal task. The attack is a disaster, the troops decimated, unable to make any headway against the German guns. And so, needing to point the finger somewhere for this failure, Mireau decides that the problem is cowardice among the troops and orders three of the surviving men to be selected at random, tried by court martial, and executed as an example to the rest. Yes, there is no question from the start that these men will be executed. The court martial, with Drax as defence counsel, is brief, perfunctory, completely uninterested in any concept of justice or in the facts of what actually happened during the attack. When Drax, in disgust, exposes Mireau’s own unacceptable part in the affair (he ordered his own artillary to fire on his own trenches), Broullard misinterprets Drax’s motives, believing that he’s playing a political game, looking to take over Mireau’s command. The General is shocked to discover that Drax is driven by a sense of moral outrage and a desire for justice. And so three men are pointlessly executed, Mireau is thrown to the wolves, and Drax heads back to the front where the pointless stupidity will go on.

The theme of cruelty and violence arising from blinkered self-interest runs through most of the films Kubrick made in the following 40 years. Perhaps it’s not so surprising after all that he made so few films; his work is that of a frustrated optimist, a man who can see too clearly that the world is a mess because of the unnecessary things that people do to each other. And that kind of vision can be exhausting to maintain.

Comments

Thanks for the insights on my favorite director.

I have a Google alert set for Paths of Glory so this article came up.

At the risk of shameless self-promotion I would like to submit the following announcement:

I’m writing to you about a film that I’ve been working on for almost four years titled, Paths of Glory: Anatomy of a Film

It’s a documentary about Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory and film making in general. rather than go on about it here, I invite you to visit the film’s website: www[dot]anatomyfilm[dot]com to learn more about it and watch clips from the edit-in-progress.

My producer and I are close to completing the film and we have launched a pledge drive on the website, Kickstarter.com, to raise finishing funds. A direct link to the project’s Kickstarter page is below:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1149150329/paths-of-glory-anatomy-of-a-film

If you love great cinema, I think you may find it interesting and hope you will consider pledging a donation. Equally appreciated will be your help in spreading word about the project and fund drive.

Thank you,

David Spodak

Film maker & Teacher

Chicago