Demons and vampires from the ’70s

Our tastes and preferences are formed in the first couple of decades of our lives. While they do continue to evolve and expand with later experience, the roots planted in those formative years run deep. This is why generations tend to be critical of the tastes of their elders and, in turn, of those who come after. My tastes were formed in the 1960s and ’70s – by what I saw in theatres, certainly, but also through broad exposure to older movies on television. For those who’ve grown up in the past two or three decades, by and large, there’s been little or no exposure to that history, so the movies’ past has had a diminishing impact on developing taste during recent decades. At the same time, I’ve had less and less interest in popular movies as more and more they’ve devolved into empty spectacles tied synergistically to larger media empires (think of the increasing garbage littering the Marvel Universe) – but for many, that spectacle has come to define the movie-going experience. Even critics heap praise on mediocre product like Wonder Woman and Black Panther.

None of this means I look back uncritically at the movies I grew up with, though I may be more forgiving of their flaws than I am of the defects of recent mainstream movies. It’s just that I recognize the part they played in creating my understanding and appreciation of cinema. That said, I’m not sure why I might originally have been drawn to the fantastic – fantasy, horror, science fiction. Even in my earliest reading, the attraction was there. In the early 1960s, when I began to read “real books”, my favourites included Norman Hunter’s tales of Professor Branestawm, the quintessential absent-minded professor (originally written in the ’30s); Clive King’s Stig of the Dump, about a boy who befriends a caveman he finds living in a nearby quarry; and H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, the first adult novel I ever read (when I was eight or nine).

My earliest movie memories are of Disney’s Pinocchio and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Ray Harryhausen’s The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts and First Men in the Moon – and Henry Levin’s Genghis Khan and Cy Endfield’s Zulu, historical epics which to a kid had an air of adventure which bordered on fantasy. On television, I was really impressed by Val Guest’s feature version of Quatermass II and the original King Kong, and watched every episode of the first three or four years of Doctor Who, all before I was uprooted and moved to Canada just before I turned twelve. Then, in my new home, I was hooked by Star Trek and reruns of The Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone.

Though I probably wasn’t aware of it at the time, the fantastic seemed inherent in the experience of watching movies – dreaming with one’s eyes open. So although I developed a taste for other genres and the intense “realism” which emerged in the late ’60s and ’70s as I went through my teens and early twenties, I was always – and still am – drawn towards fantasy and horror and perhaps remain more forgiving of the flaws in genre films than I am of other forms (straight drama, comedy, etc).

Which is all preamble to my recent revisiting of two horror movies from the ’70s which I originally saw in their first theatrical runs. One is a scrappy ultra-low-budget production which takes familiar elements and makes them fresh and original; the other more mainstream – modestly budgeted, but graced with a surprisingly high profile cast. As entertaining as the latter might be, it’s the more obscure film which really impresses.

*

The Manitou (William Girdler, 1978)

William Girdler had a brief career, beginning with regional exploitation features (3 On a Meathook, Asylum of Satan [both 1972], The Zebra Killer [1974]), moving on to blaxploitation (Abby [1974], Sheba Baby [1975]) and shot-in-the-Philippines action (Project: Kill [1976]), before hitting his stride with a pair of nature’s-revenge movies (Grizzly [1976], Day of the Animals [1977]) which were surprisingly successful at the box office. He made just one more movie before his death at age thirty in a helicopter crash in the Philippines in January 1978 and, as is quite often the case, his reputation became somewhat inflated postmortem – some admirers have even claimed he could have been another Spielberg if he had gone on to make more movies. (A similar but perhaps more convincing argument could be made for Michael Reeves, who died even younger.) But whatever value Girdler’s nine completed features may have, he never exhibited the ease and polish which was evident even at the beginning of Spielberg’s career.

Girdler’s final feature is quite unlike his previous work and seems to represent his bid to move up the production ladder. It has the look of a studio movie, albeit still made on a relatively low budget. The cast has some big names and, although financial limitations somewhat undermine the attempt at a spectacular, effects-heavy climax, it’s on a par with other mainstream horror movies of the period, like Michael Winner’s The Sentinel and Don Taylor’s Damien: Omen II. What it doesn’t have is the kind of visceral energy which characterized Girdler’s earlier work. While The Manitou (1978) is an entertaining supernatural thriller, there are issues with tone which keep it from being a more memorable horror movie. It has the feel of something softened in order to attract a wider audience – “family-friendly” horror.

get their first look at Misquamacus

The Manitou is the story of a young woman who abruptly develops a rapidly growing tumour on her back, which quickly evolves into a mysterious embryo. (A precursor to David Cronenberg’s The Brood, made the following year?) When doctors are unable to explain or deal with the growth, she calls on her old lover, Harry Erskine (Tony Curtis), a fake medium who bilks old ladies with his Tarot deck. With the doctors baffled, Harry has to do the detective work which finally reveals that the growth is actually a reincarnating Native American medicine man, the powerful Misquamacus (a name drawn from The Lurker at the Threshold, one of August Derleth’s “posthumous collaborations” with H.P. Lovecraft). Harry enlists the aid of a modern medicine man, John Singing Rock (Michael Ansara), to counter malevolent magic with more benign powers.

Built into the story – adapted from prolific British author Graham Masterton’s first novel – is some sympathy for Misquamacus, a “demon” driven by anger towards those who perpetrated genocide on the original inhabitants of the continent. When he proves too powerful for John’s traditional magic, it falls to Harry to harness the energies of modern technology to send the reborn medicine man back to the supernatural realm … a bitter irony given the history of Europeans decimating the Native American population.

But while this theme is present in the movie, it’s only there because of the source material. Girdler doesn’t elaborate on it as he concentrates on Harry as a semi-comic character unexpectedly caught by a dawning awareness that there’s a reality underlying his cheap scams. There are a few moments of horror – an orderly is skinned alive (off-camera) by the newly born Misquamacus – but the attempt at an epic occult battle in the final act is undermined by budgetary limitations. As the hospital floor becomes an ice cave which opens into cosmic space, the underpopulated cast keeps the stakes low and all the styrofoam ice looks cheap and unconvincing, as do the cosmic opticals.

Girdler aims paradoxically for both comic effect and epic scale, in the process losing the potential seriousness of Masterton’s main theme. Which is too bad because the cast is so good. Curtis’ Harry could have used a darker core, but Ansara’s medicine man comes close to embodying the deeper theme. Susan Strasberg adds a touching vulnerability to the underwritten role of unwitting host Karen Tandy, while Burgess Meredith makes the most of his single scene as an absent-minded expert in Native mythology and Stella Stevens (in a disconcertingly artificial tan) is charming as Harry’s friend Amelia, a genuine medium.

Although Masterton’s novel is pulpier than William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, and lacks the latter’s pretension, the film would have benefited from a more serious approach akin to William Friedkin’s attempt to treat the supernatural with a degree of realism. Girdler’s apparent unsuitability for the material results in a tone which frequently works against the horror elements, but as it stands The Manitou is a minor but enjoyable slice of ’70s horror. The use of Native American mythology (though this raises inevitable questions about cultural appropriation) gives the movie an unfamiliar narrative hook and that freshness combines with an engaging cast to go some way towards balancing its shortcomings.

*

Grave of the Vampire (John Hayes, 1972)

If The Manitou was largely dismissed by critics in 1978, John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire didn’t even get that much notice and barely left a trace when it was released in 1972. This is largely explained not by the movie’s intrinsic qualities, but rather by its status as an ultra-low-budget piece of exploitation. (It was reputedly made for about $50,000 – approximately one-sixtieth of The Manitou’s budget.) Director John Hayes was a prolific filmmaker in the 1960s and ’70s, working on the fringes of the industry. In 1958, he had written and produced a half-hour short in New York called The Kiss, which was nominated for a Best Short Subject Oscar, but what came after was a largely disreputable flood of sex, crime and occasional horror, which in the ’70s dipped into outright porn. But even there, his generally sour attitude towards sexuality and gender relations made for anti-erotic forays like Baby Rosemary (1976).

Grave of the Vampire may well be the best movie Hayes ever made, one which overcomes limited resources thanks to an interesting script (the only feature written by David Chase, who eventually went on to create The Sopranos, until 2012’s Not Fade Away), a generally committed cast and an innovative approach to vampire lore. Even the cliched elements are twisted into something new and unexpected. Although I haven’t seen it mentioned anywhere else, it seems possible that Hayes’ movie had some influence on the creation of Blade, who first appeared as a comic book character in 1973, a year after the film’s release. Both feature a human-vampire hybrid who is driven to seek out and kill the supernatural monsters who made them outcasts from human society.

But Grave of the Vampire is a bit darker. While in Blade, the hero’s pregnant mother is bitten, transforming the fetus, in Hayes’ film James Eastman (William Smith) is the product of a rape – while necking with her boyfriend in a graveyard in 1940, his mother (Kitty Vallacher) is dragged by the newly woken Caleb Croft (Michael Pataki) to an open grave and assaulted. Later, she discovers she is pregnant and the doctor tells her that the baby is essentially dead, but still feeding off her. He insists that she get an abortion, but believing that the child was fathered by her now-dead boyfriend rather than the rapist, she’s determined to keep it.

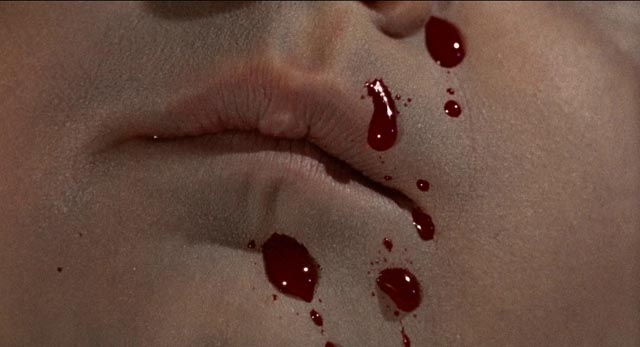

After a difficult birth, the baby quickly begins to wither, refusing to take milk. Only when his mother accidentally cuts her finger and the blood drips on the baby’s lips does she realize what he needs. The image of the baby licking its bloody lips is just one of many disturbingly transgressive things in the film. The mother takes a knife and cuts her own breast to allow the child to feed, and later uses a syringe to draw blood (graphically) from her arm to fill its bottle. Without overstating the point, the imagery links the vampire’s craving for blood to drug addiction (a theme explored in more detail decades later by Larry Fessenden in Habit and Abel Ferrera in The Addiction [both 1995]).

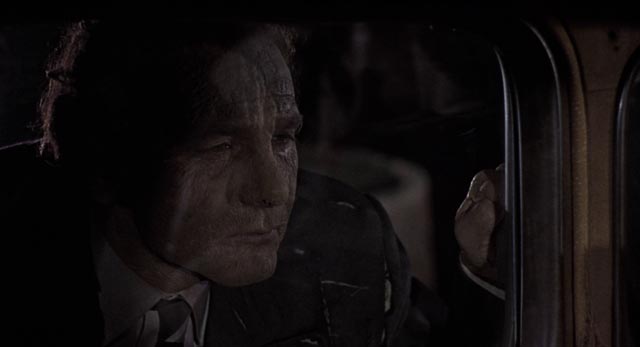

Eastman keeps his feral nature in check by eating raw steak and is able to move freely in daylight, but others, it turns out, have no desire to resist vampirism. After his mother’s death, the bitter outsider goes in search of his father, finding him settled under the name Lockwood as a history professor at a small-town college, teaching night courses in the anthropology of religion and superstition. These courses are apparently very popular and prospective students are turned away for lack of seats before Lockwood launches into a monologue about irrational but potent superstitions. Eastman speaks up about vampires, explaining that he’s working on a paper about a particularly depraved figure from the 1700s who became one of the undead, and was eventually executed in the 1930s for rape and murder. The body, having been transported to California and placed in a tomb, disappeared several years later on the night the young couple were attacked in the graveyard. The back and forth between Lockwood and Eastman carries undercurrents apparent to both but unnoticed by the other students.

This scene highlights the qualities of Chase’s script and the conscious awareness of the actors and director of the generic elements in play. It’s a smart, tense sequence which plays convincingly (unlike many such classroom scenes in B-movies). Lockwood knows that he’s been identified, but as yet not who his antagonist might be. But Eastman isn’t the only one who has come to the class because of the teacher’s true identity. While Lockwood is drawn to Anne Arthur (Lyn Peters) because she resembles his long-lost wife, he’s being stalked by Anita Jacoby (Diane Holden) who wants to become a vampire herself, to live eternally as his new bride. She miscalculates the monster’s feral nature and pays for it with her life.

As Lockwood closes in on Anne, Eastman closes in on him for a final confrontation which culminates in a brutal, animalistic fight which paradoxically, in the moment of Eastman’s triumph over his despicable father, unleashes the monster which has until now been kept at bay inside the son.

Dark and atmospheric, Grave of the Vampire rises above its limitations and the occasional cliches to create an original treatment of the familiar story of vampire and vampire hunter. Michael Pataki is one of the finest cinematic bloodsuckers, a savage amoral animal masquerading as a sophisticated man, and Holden is very good as a woman who ultimately misunderstands the power she desires. William Smith has received a lot of criticism as Eastman – he’s a big rugged guy most familiar from 1960s biker movies – but I actually like his performance; for all its stiffness, it evokes the deep social separation he feels from all the people around him and undercuts the romantic convention of his brief relationship with Anne. Keeping the monster in himself contained, this relationship is little more than an attempt to perform some kind of human normality, something transient and doomed because in the end, he can only be a threat to her survival.

Perhaps inspired by the script, Hayes as director and editor invests the film with an oppressively dark atmosphere – Lockwood’s vampiric attacks are brutally visceral – and at times plays with viewer expectations in interesting ways. The title sequence is itself disconcerting, played out over a medium shot which slowly tracks sideways around Croft’s tomb with fog wafting around it while we hear the sounds of a heartbeat and breathing mixed with a subtle theme by composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava. After the director’s credit, the shot holds for a full thirty seconds, building a sense of some impending menace before cutting to the exterior of a brightly lit frat house with a party underway. When a young couple leave the party and drive to the seclusion of the graveyard for some serious making out, we already know that they’re doomed because of the previously built tension – and yet we’re still unprepared for the viciousness of what happens next as the partially decayed Croft climbs out of his tomb and stalks the couple. The girl is paralyzed with fear as Croft kills her boyfriend by dropping him across a gravestone, snapping his spine; by the time he drags her into the open grave, we don’t have to see any details of what he does to feel the full horror of it.

Although Grave of the Vampire may lack the poetic elements of Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural or Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess, both made the following year, it ranks with those films as one of the finest cinematic treatments of the vampire from the period – all of them being far more original and innovative than the more commercially successful Count Yorga, Vampire and its sequel (1970, 1971) which launched the vampire into contemporary America.

*

Both The Manitou and Grave of the Vampire have been treated well by Shout! Factory, the latter in particular benefiting from a Hi-Def transfer. Even though the print source is a bit battered, this disk rescues the film from decades of truly awful public domain releases on VHS and DVD. Surprisingly, the bigger-budgeted The Manitou fares less well, despite featuring a 4K transfer – no doubt the print source is to blame for the weaknesses in the image, which is somewhat flat and occasionally muddy and lacking in fine detail.

Both films get enthusiastic but not uncritical commentaries from Troy Howarth, with Grave having a second commentary from Nathaniel Thompson and Howard Berger. The Manitou also has interview featurettes with producer David Shelton and author Graham Masterton.

Comments