Sex-Death-Exploitation-Art

What to say about Jörg Buttgereit? The notoriously transgressive German filmmaker, whose work was caught up in the Video Nasty craziness in Britain and suppressed and prosecuted in Germany, has over the past three decades gained critical respect along with the adoration of fans who were drawn to him specifically because his films aggressively assaulted social standards of good taste. Having begun making short 8mm movies in his teens, Buttgereit was at first a precocious kid drawn to the tropes of horror – a genre all but non-existent in Germany since the Second World War because real life horrors had overwhelmed the national imagination.

Those short films – featuring the likes of Dracula and Frankenstein – were (at least from the evidence of what’s available on various Blu-rays) essentially adolescent goofs, clumsy but enthusiastic. It was while making his long short Hot Love in 1985 that he met Franz Rodenkirchen, an encounter fated to push him to a whole new creative level. At the age of 23, the pair set out to make what became an outrageous offense embraced by an underground and punk audience.

Nekromantik (1987) remains a landmark in the unflinching depiction of necrophilia – equalled only by its sequel Nekromantik 2 (1991). Few filmmakers have dared to conflate sex and death so graphically and the fact that thirty years later the film still has the power to disturb viewers on such a deep level attests to Buttgereit’s seriousness as a filmmaker; its shocks are not superficial and transitory, but rather infused with artistic purpose. The fact that it was shot on 8mm with virtually no budget makes it that much more impressive.

Having grown up in a society which had all but banned horror as a form of entertainment and in a time when his generation was pushing back against a status quo imposed by those who had personal experience of the real-world horrors of the Third Reich, it was not surprising that Buttgereit would be drawn to themes which would assault the governing complacency of contemporary German culture. He belonged to a generation whose anger manifested in a transgressive underground art scene and the anarchy of punk.

Among the dominant ideas which shaped Buttgereit and Rodenkirchen’s first collaboration were body horror – the inevitability of sickness, death and decay, which had also been central for the past decade or so to the work of artists like David Cronenberg – and a rejection of the sanitized treatment of death in mainstream movies. The latter had been a significant force in the work of Sam Peckinpah, but while he didn’t shy away from the graphic depiction of shattered bodies, he transformed cinematic death into another form of aestheticism. Partly because of budgetary limitations, the home-made feel of Buttgereit’s 8mm movie makes his depiction of death seem more direct, far more uncomfortable. Style precludes distance.

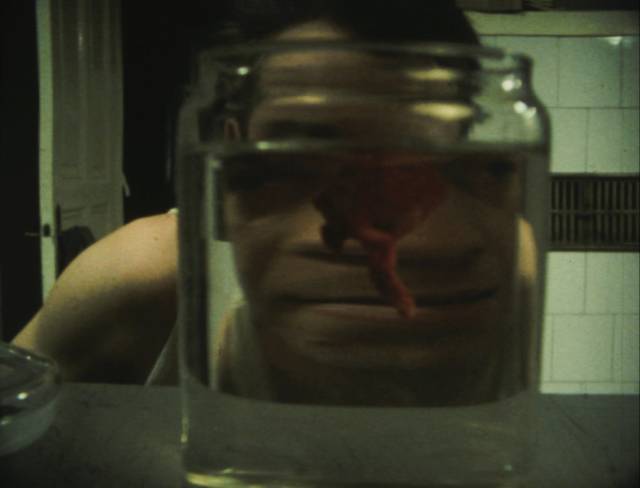

In Nekromantik, Rob (Daktari Lorenz) works for a company which cleans up after accidents, bagging up shattered and torn bodies. He manages to slip various parts – a limb here, an organ there – into take-home bags, adding them to a collection which fills several shelves of jars preserving the pieces, which he and his wife Betty (Beatrice M.) like to take out and fondle. These fragments of other bodies form an erotic bond between the couple.

Then one day, Rob manages to steal an entire body – one already in a state of decay, having been buried in a ditch for some time. Discoloured, leaky and disturbing in its reminder of where all bodies are destined to go, it amplifies the interweaving of eroticism and death between Rob and Betty, becoming an integral element in their sex lives. In fact, its power is such that Betty becomes increasingly attached to it and frustrated with Rob’s general passivity. When he loses his job, she takes the body and leaves him; in despair, he commits suicide, death itself becoming a climactic sexual experience.

The unflinching depiction of the couple’s relationship with the corpse pushes the viewer’s tolerance for transgressive imagery – there are times where it’s virtually impossible not to look away – and yet the film’s tone is strangely romantic, almost sweet. It’s a love story in which a relationship evolves and one partner’s affections are eventually transferred to a third party who was introduced into the relationship by the one who is eventually rejected.

The mixture of attraction and repulsion runs through all four of the features Buttgereit and Rodenkirchen made together. These films erase the divide between life and death, presenting instead a continuity which carries complicated emotions across what is typically seen to be an absolute divide. This is particularly true in Nekromantik 2 (1991), their third collaboration.

Rob, freshly buried, is dug up by a young woman named Monika (Monika M.), who takes him home and makes love to him. (Later, Betty turns up at his grave, wanting to dig him up for herself.) Monika enters a more “normal” relationship with Mark (Mark Reeder) after he offers her an extra ticket he has for a movie, having been stood up at the theatre. In this film Buttgereit is more overtly self-referential; Mark works as a voice-over actor for porno films (not much dialogue, but a lot of heavy breathing and groans), while the movie he watches with Monika is a deadpan parody of tediously pretentious art films – long tracking shots around a naked couple sitting at a rooftop table eating lunch and engaging in meaningless conversation.

Mark is a bit goofy, pleased to have Monika’s attention … until he drops by to find her and a group of friends sitting around watching a video of very graphic dolphin autopsies. His disgust at what she finds fascinating alters her opinion of him. Having dismembered Ron’s decaying corpse, she beheads Mark during sex and adds Rob’s severed head to Mark’s body as she finishes copulating.

There’s a slightly juvenile streak to the Nekromantik movies, an obvious desire to stick a messy finger in the eye of bourgeois propriety. But there’s something more, something deeper too. These films aren’t like a Herschell Gordon Lewis gore-fest, though their initial, enthusiastic audience was mostly fans of extreme horror. Buttgereit serves them well with some disturbingly convincing, grotesquely moist corpses with whom Rob, Betty and Monika get extremely intimate. But the films are also well-crafted, skilfully photographed and edited, with excellent scores by Hermann Kopp, Daktari Lorenz, John Boy Walton and Monika M. It’s this level of cinematic craft which makes them seriously disturbing rather than jokey, though there is undeniable humour.

In the two Nekromantik movies Buttgereit supports the gross-out exploitation with filmmaking artistry. In his other two collaborations with Franz Rodenkirchen, he salts the artistry with disturbingly transgressive elements. Both Der Todesking (1990) and Schramm (1993) use disturbing imagery to explore the intricate and unsettling connections between life and death on a more philosophical level. The strange sense of playfulness has been supplanted by a grim, poetic seriousness.

Der Todesking was conceived in part as a rebuke of the gore fans, those who had given Buttgereit a degree of cult success largely because of the gross-outs. This second feature deliberately asserts that death is not in fact a source of entertainment and fun – in that sense, it’s anti-exploitation despite offering nothing but moments of death, specifically suicide. Deeply melancholy, it reverses the perverse normalization of death in Nekromantik 1 and 2 and makes it mysterious and unknowable again.

Beginning with a young girl in a playground sketching a skeletal figure which she dubs Der Todesking, The Death King, a mythical figure who “makes people want to die”, Buttgereit has said that “there is no message … it’s just a film about death”. In seven vignettes spread across seven days, we see a series of people kill themselves, without knowing anything about their pasts or their motives; Buttgereit’s point is that we never can know the reasons for such a drastic act. Interspersed between these scenes, he shows a corpse decaying in time-lapse, disintegrating under the onslaught of countless insects, streams of maggots flowing over and inside the body as it gradually falls apart. This was an elaborate creation which, while perhaps not entirely realistic, possesses an awful poetic realism, a vision of what waits on the far side of each act of self-annihilation.

Each sequence has its own style, the first using a virtuoso circular pan to observe all the mundane actions of a man – writing letters, phoning his employer to offer his resignation, cleaning, feeding his fish – surveying the room in a continuous movement as it catches passing glimpses of the man’s activities before he moves to the bathroom, gets in the tub, takes large numbers of pills and slips below the surface to drown. In the second, a man visits a video store and rents a cheesy Nazisploitation tape (a nod to the absurdity of Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS). Watching the sordid tortures back home on television, he’s interrupted by his wife, who nags him about wasting his time; he pulls out a gun and shoots her, then takes a picture frame and hangs it around the blood splattered on the wall … at which point we pull back to see that all this is also on a TV screen. The camera continues to pull back to reveal a woman’s legs hanging nearby; here we don’t even see the actual suicide victim.

Next, an apparently depressed woman walks through rain and sits on a park bench. There’s a man already there, soaked through. He starts talking to her about sexual problems in his marriage; she takes out a gun and points it at him, but it isn’t cocked and the trigger just clicks. He takes it from her, puts the barrel in his mouth and the camera pans away before we hear the shot. In the following sequence, we don’t see anyone: the camera explores the structure of a very high bridge and on-screen titles list the names, ages and identities of the numerous people who have thrown themselves off the bridge.

On the next day, a lonely woman watches her neighbours from her window, a young couple who seem to begin making love before disappearing inside. She sneaks down the stairs, trying to spy on them through the mail slot. On the way, she finds an envelope outside her door, with identical envelopes outside all the other doors. Back in her own apartment she reads the letter, which enthusiastically urges the reader to commit suicide as the only free act available to us. Dismissing the letter, she phones her neighbour but gets no reply. A cut reveals the young couple dead in a suicidal embrace on their bed.

In the next sequence, someone off screen is viewing several reels of 16mm film. We see the cameraperson as she turns it towards a mirror; she has a rig strapped on with the camera at shoulder height. In one hand, she has a pistol which she points at herself in the mirror. In the next reel, the camera tracks into a club where a band is playing. The camera approaches the stage and, like a first-person-shooter game, the gun rises into frame and the singer is shot; the camera swings round to face the audience, and the gun fires randomly into the panicking crowd … until one audience member points a gun back at the camera and the image goes black.

After this, the most elaborate sequence, Buttgereit ends with the most chillingly simple scene: A man wakes up, gets out of bed, and begins smashing his head against the wall, killing himself through a sheer act of will.

With no narrative line, very little dialogue, no characters to become engaged with, and a (relatively) sparing use of gore, Buttgereit refuses to supply his Nekromantik fans with the thrills they were expecting and not surprisingly many of them considered Der Todesking boring and pointless. In fact, it seems more like something you’d find in an art gallery than a grindhouse, a sober, melancholy contemplation of despair about the pointlessness of existence.

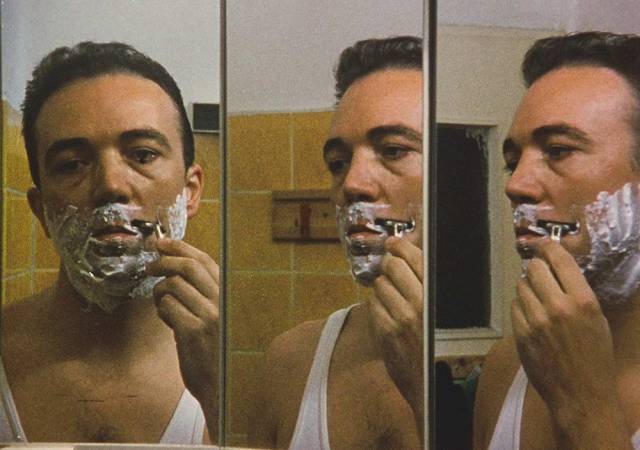

While Der Todesking presents the enigmatic moments leading up to death, framed by glimpses of the aftermath in that decaying corpse, Buttgereit and Rodenkirchen’s final collaboration, Schramm, is trapped in the actual moment of death, looping through memories and dreams which keep repeating as Lothar Schramm (Florian Koerner von Gustorf) fades into nothingness.

At the start, we see a newspaper headline declaring the “lonely death of the Lipstick Killer”. Then Schramm is sprawled on the floor in a pool of blood and white paint. Someone is insistently knocking on the door as the camera closes in on his dying eye. In this moment, his mind recalls another knock and he opens the door to a smiling pair of Christian evangelists who want to share the Word with him. He invites them in, his manner welcoming and pleasant; he offers them something to drink and as they sit on his couch he disappears into the kitchen. Ironically, the couple seem slightly suspicious of his lack of resistance – they’re all too used to being rejected.

Schramm returns from the kitchen with a large knife and proceeds to hack away at the man’s throat while the woman, in shock, stares in disbelief. Failing to make her escape, she is attacked with a hammer. Schramm calmly arranges the bodies in various sexual positions, taking Polaroid pictures. The apartment is a mess, with blood spattered on walls and ceilings. Schramm proceeds to use a roller to paint over the mess, eventually climbing a shaky ladder to reach the high spots … the ladder he has already fallen off at the start of the film. Buttergereit circles back to each of these elements repeatedly, illuminating not just that Schramm is an apparently affectless killer, but that ultimately he is one of his own victims, his acts forming a kind of displaced suicide.

While Buttgereit avoids any attempt at psychologizing the character, he does want the audience to experience everything from Schramm’s point of view – as indicated by the full title, Schramm: Into the Mind of a Serial Killer. We see a collage of subjective impressions evoking a mind disconnected from, if not at war with, its own body. He has dreams and visions of his own dismemberment, waking to find his leg severed, poking the bloody stump with his fingers; he has his teeth ripped out by a dentist with pliers; a surgeon removes an eye with a scalpel. His ultimate fall from the ladder comes because he … imagines is probably the wrong word; he experiences his leg as having been amputated and replaced with an unstable artificial limb which causes him to lose his balance.

Whichever came first is unclear, but his brutal murders seem to be an extension of this war with his own body, striking out against the horror of being a corporeal entity. But trapped as he is, he is nonetheless capable of playing a normal human being. This is seen in his relationship with his neighbour Marianne (Monika M. again), a young prostitute who sometimes leans on him as an alternative to all the transactional “relationships” with her clients. He helps her out occasionally, and they go out to dinner together. And when a couple of older men ask her to visit them at another location rather than in her own flat, and she feels nervous, Schramm agrees to drive her there in his cab and wait until she’s done.

Because the film stays so close to his point of view, we are left to deduce for ourselves what she experiences in the big house with a group of older men. The main clue is a glimpse Schramm gets from the street of her at the door dressed in what appears to be a Hitler Youth uniform – definitely not a good sign, although afterwards she doesn’t seem too troubled.

For a while Schramm’s relationship with Marianne appears potentially redemptive – but only until one evening when she joins him for a drink and he drugs and molests her, something she remains unaware of, but which distances the viewer from him. Which in itself seems odd in retrospect: we’ve already seen him commit brutal murders, yet tied as we are to his own perspective, we have until this point maintained a degree of empathy. It’s his betrayal of Marianne’s trust rather than the murders which causes us to seek some distance from him, which in itself becomes an interesting study in how audiences relate to and identify with characters on screen – what can we accept, what do we reject, and just how complicit are we with the behaviour we sit back and observe?

Schramm’s own conflicted relationship with himself leads to the film’s most uncomfortable sequence – one which brought to mind one of many disturbing moments in Kirby Dick’s documentary Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist (1997). By the time Schramm climbs that ladder to paint over the blood – in itself a seemingly futile act as the blood mixes with the white paint as he runs the roller over the wall; there is finally no concealing his own terrible actions – his attack on his body has apparently triggered a deadly rebellion against him by that body. His internal civil war can have only one end.

As the life fades from him, the film finally steps out of his stifling subjectivity. That knocking on the door is Marianne, come once again to seek his protection as she heads back to the old men in the mansion. Getting no reply, feeling betrayed that he isn’t there to help her (ironically, because she remains unaware of his real earlier betrayal, while this time being dead gives him an excuse), she goes off alone and the film ends with a glimpse of her dressed again in the Hitler Youth uniform, but now bound and gagged and waiting for something no doubt awful to be done to her. Buttgereit has left Schramm’s hermetically sealed world to reveal a larger corruption in the society which somehow produced him. The suggestion of Fascism may be an easy form of shorthand, but it does evoke a contrast between Schramm’s “retail” violence and the potentially much larger-scale horrors of which wealth and privilege are capable. As Virginia Selavy suggests in an essay in the book which accompanies the disk, there is a parallel here between Schramm and Fritz Lang’s M (1931), a perpetual tension between individual acts and the actions of social and political groups.

*

Watching Jörg Buttgereit’s four features inevitably raises the question of what draws me to such disturbing, transgressive films? To some degree, it’s a desire to test my own complacency. I’ve managed to live a largely untroubled life while being quite aware that vast numbers of people haven’t been so privileged. But then there’s the risk of being a misery tourist … I’m really not sure that there’s a good and clear answer. I certainly don’t embrace everything which pushes the limits of bourgeois taste. When I sense a morally suspect intention – particularly when it seems that a filmmaker enjoys and expects me to enjoy the sheer spectacle of violence and pain, to identify with perpetrators rather than victims, I’m repulsed (Quentin Tarantino and Eli Roth for instance). But if, in contrast, I sense that a filmmaker is seriously trying to explore and understand uncomfortable aspects of being human, looking at our potential for darkness not to wallow in it but rather to own it in a way that might make resistance possible, then even if it takes an effort not to look away, I am willing to look beyond my repulsion. This is as true of these films by Buttgereit as it is of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), or Joshua Oppenheimer’s chilling documentaries The Act of Killing (2012) and The Look of Silence (2014).

*

Arrow’s editions of all four films are so packed with extras that you get the impression they want to deflect accusations of releasing movies which are merely offensive. Each film is surrounded with something like three hours of documentaries, interviews, outtakes, short films and music videos, as well as commentaries from Buttgereit and some of his collaborators. I’ve only dipped into this material, but Buttgereit comes across as an engaging, intelligent, serious artist who also has a sense of humour.

I regret now not having bought the original limited editions of the two Nekromantik movies, which each came with a soundtrack CD and book in a slipcase. The standard editions have no text supplements and no CDs, just BD and DVD disks, although the Nekromantik 2 disk includes a complete 20-track recording of a live soundtrack concert as a BD-ROM extra. The inclusion of the soundtracks is welcome, as the music is really important to all the films, adding power and nuance to the imagery.

The special editions of Der Todesking and Schramm both come with soundtrack CDs and substantial booklets of essays and interviews – Kat Ellinger’s essay in the Todesking booklet is particularly useful, linking Buttgereit’s work to Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty.

Comments