DVD of the Week: Video Nasties, The Definitive Guide (2010)

Issues of censorship and freedom of speech are always more complicated than we’d like. It’s never just simply a clear cut question of “this” or “that”. The complete denial that certain elements of pop culture, for instance, can’t possibly do anyone any harm under any circumstances, doesn’t really hold up – of course some people are going to be adversely affected by some of the things they see and hear. But the idea that global bans on certain classes of books, movies, music, etc, will somehow eliminate whole ranges of social problems is demonstrably false. And the idea that most people need to be protected because they are not capable of deciding for themselves what to read or watch or listen to is sheer paternalism.

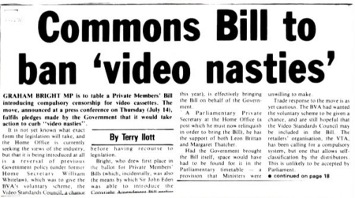

What a new and highly engaging DVD has to say about these questions is very illuminating. Nucleus Films’ release of Video Nasties: The Definitive Guide (2010) is a terrific three-disk set devoted to the uproar in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain over the availability of violent movies in the new home-video market. The set is anchored by a very well made documentary (directed by Jake West) called Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship and Videotape, featuring interviews with filmmakers, critics, academics and also two of the major players in stirring up the controversy and prompting the government to pass the law to ban the “nasties” — Graham Bright, at the time a neophyte Conservative back-bencher whose private member’s censorship bill eventually became law, and Peter Kruger, a senior police officer.

The timing of the uproar is not, in retrospect, very surprising. A number of factors converged in the early ’80s. The loosening of restrictions on violence and sex in movies during the ’70s merged with the availability of new video technology to undermine existing social controls over movies. Until then, movies were seen either in theatres or on television, in both cases easy for social watchdogs to monitor. In the U.S., the MPAA had their ratings which affected how, and even whether, a particular movie was distributed and exhibited; the BBFC in Britain had previously possessed great powers of censorship and even the ability to ban films outright. Ironically, the “nasties” erupted just as British censorship was giving way to the idea of ratings as a guide to viewers: although the BBFC was still empowered to order cuts in theatrically distributed movies, it was less clear what, if any, rules there were for videos intended for private home viewing.

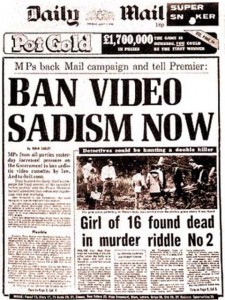

As these issues were bubbling to the surface, Margaret Thatcher had been in power for several years and things were no longer going so well for her. Crime, unemployment, the Falklands war – all these things were shaking her government’s authority. What better then than a “moral issue” to divert attention and reassert the Conservatives’ authority to rule? This was also the time of Mary Whitehouse and the Festival of Light, a prominent movement to counter what was seen as the dissolution of moral and social standards. Whitehouse was allied to Thatcher and, in fact, personally urged Bright to draw up his proposed bill against all this sordid new “entertainment”.

And, as often happens in situations like this, it could all be cast as an effort to “protect the children”. As academic Martin Barker, one of the main characters in West’s documentary, points out, the whole “nasties” scare was launched on almost exactly the same terms as the great horror comics scare of the ’50s, right down to using Frederick Wertham’s terminology of “the seduction of the innocent”. What it amounted to was the assertion that unfettered access to sordid movies on videotape would destroy the youth of the country, in fact would transform them en masse into soulless serial killers.

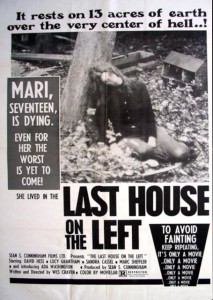

What is even more clear is the class basis of the whole thing: all these concerned middle class people somehow manage to look at this appalling stuff without themselves being corrupted, but they know with absolute certainty that the lower classes don’t possess the intellectual abilities to protect themselves from such pernicious influences: they need their betters to protect them. What is most amusing about this is the fact that the average viewer of this kind of entertainment generally watches with a sense of amusement, or in the spirit of testing their own capacity to endure the extremes being depicted, knowing full well what the distributors of The Last House On the Left assured them in their advertising: “it’s only a movie.” The moralists, on the other hand seemed largely unable to make the distinction and, in fact, in the documentary quite openly assert that they believe that many of these are actually “snuff” movies, that they really do show people being killed. Looking down on this “lower class” form of entertainment, they completely lack the critical ability to discern what is real and what is fake.

Barker illustrates the dishonest tactics of the crusaders with his account of a study conducted to discover what the harmful effects of these movies might be (Bright asserts in a television clip from the time, before the study was even completed, that the results would prove that these movies were harmful to children – and dogs! … yes, he actually said this on television); when the academic in charge of the study was unwilling to provide the requested “facts”, the backers seized all the research materials and released a report which was full of completely false “statistics”: based on a very small, highly manipulated sample, it was claimed that more than 40% of British children aged five had seen at least one of these terrible films, a “fact” which was endlessly repeated in the right-wing press. Based on that bogus report, Parliament quickly passed Bright’s bill into law and prosecutions got underway.

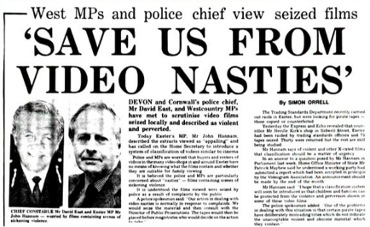

And so, small shopkeepers, video dealers, distributors … all were suddenly faced with the prospect of becoming criminals merely from the distribution of a number of movies, but with no clear idea of what was actually illegal. In fact, some films which had been passed for theatrical showing by the BBFC were suddenly illegal on video. The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), in league with an overly eager police force (thousands of tapes were seized and burned), eventually drew up lists of banned films.

This is where the ridiculousness of the attempt to exert control through criminalization becomes fully apparent. First, not surprisingly, large mainstream film companies managed to escape prosecution, while a lot of small independents were run out of business by the costs of submitting every title for BBFC rating, or prosecuted, and at least one even jailed with a more severe sentence than if he had been dealing drugs. As QC David Hamilton Grant points out, this man was sent to prison for distributing a tape which contained just 15 seconds of material which the BBFC had ordered cut from the theatrical release; and as Kim Newman says, this means that at some point someone had to have seen the theatrical film, then seen the videotape and spotted those extra few seconds, and then have filed a complaint! That level of obsession is scarier than whatever might have been in the movie itself.

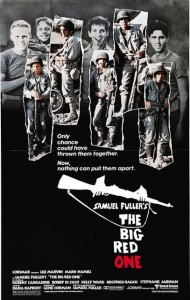

Second, the titles chosen for banning were more or less random. In fact, as is made quite clear in the documentary, it was often the packaging and advertising methods rather than the actual content of the movies which brought down the wrath of the authorities. And as more than one interviewee comments, it could be said that the distributors brought it on themselves with their excessive claims of gore, savagery, torture, etc. (which usually went far beyond what was actually shown in the movie). Anything with “cannibal” in the title would be nailed – but also, at one point or another, Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One (apparently someone mistakenly thought the title referred to a particular sex organ) and even the Dolly Parton-Burt Reynolds musical The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas were briefly seized.

Because many of the movies in question were in fact rather disreputable, both in terms of poor production values and extreme content, it was difficult to find anyone willing to stand up in court to defend them (Guardian critic Derek Malcolm provides an amusing anecdote about his own attempt, which provoked outrage from the judge). The fact was, even the Left was appalled by these movies. But on the whole, the Left kept quiet while the Right went to absurd lengths to blame these movies for pretty much everything that was happening in the country. At one point the documentary shows a brief newspaper clipping about someone dubbed “the pony maniac” who was going about harming horses; the explanation offered by the police was that the perpetrator was affected by either the new moon or video nasties. Another newspaper showed an illustration of a TV set with Satan looming over it – and, indeed, Graham Bright actually refers to the videos as “evil”.

Eventually, the DPP drew up a list of the forbidden films. But it was unstable as prosecutions in one part of the country would gain a guilty verdict, while the same film would be found not guilty somewhere else. By the time things settled, there was an official list of 39 banned films. Another 33 films were at one time included, but ended up being dropped for one reason or another. Looking at these lists now, it’s hard to believe that those who compiled them could have been unaware of the complete arbitrariness of what was included. Not surprisingly, these lists quickly became a “must have” guide for fans of trashy and offensive entertainment.

As a final irony, it was discovered recently that for technical reasons the law was not in fact properly enacted and so all the people who were persecuted, put on trial, fined or imprisoned were done so illegally. Earlier this year, the government hastily re-enacted the law to make it “legitimate”, but no apologies and compensation have been offered to the people who were actually done harm during the scare.

Today, many of the films on these lists are widely available in uncut form, and a number of them have received glossy Hollywood makeovers in recent years. As Martin Barker points out, this kind of “moral panic” is a recurring phenomenon – the horror comics, the “nasties”, videogames in more recent years – but once it has served its immediate purpose (to re-establish social control through “moral authority”), it fades into the background until the next time. And each time there’s a new eruption, somehow we’ve forgotten about the last occurrence and the fact that those comics, those movies, those videogames did not actually bring about the collapse of our civilization, and we get sucked into it all over again.

The two supplementary disks in the Video Nasties set present trailers for all these movies along with introductions and comments by many of the people featured in the documentary – author/critics Kim Newman, Alan Jones, Stephen Thrower, Brad Stevens, academics Patricia MacCormack and Julian Petley, and others. Amounting to 7 ½ hours in total, this material constitutes much more than “an extra” and in fact is a terrific complement to the documentary. Altogether the set provides a rich history of a contested moment in popular culture.

The contents of the two DPP lists deserve closer examination, so I’ll look at them in a subsequent post.

Comments