Speed reviewing: 50 Capsule Comments

With the amount I watch, I could be posting here every day … but I just don’t have the time. My weekly posts only reflect a small part of what I spend a ridiculous amount of time viewing. I often mean to get around to saying something about a movie only to find it pushed aside by something more recent. So here, just to indicate the range and variety of my (sometimes dubious) tastes, are very brief comments on some (but still not all!) of the movies and TV shows I’ve seen in the past three months or so, but haven’t yet written about (during the same period, I’ve posted reviews of forty other movies):

Movies

The Stranger (Orson Welles, 1946): After the butchery of The Magnificent Ambersons and the debacle of It’s All True, Orson Welles made a last-ditch effort with this post-war thriller to prove that he was capable of working effectively within the studio system. The proof is here; it’s a well-crafted, well-acted, atmospherically photographed little movie about an investigator who tracks a high-level Nazi to a small New England town where he’s embedded himself firmly in the community. But despite his best efforts, Welles couldn’t regain the trust of the studio bosses. His follow-up, The Lady from Shanghai, poked a finger in their eye before he confounded the industry by making an expressionist Macbeth at, of all places, Republic Studios (home of B-westerns and cliff-hanger serials), and then high-tailed it for Europe and a vagabond career where he created a series of remarkable films on his own terms.

Where Eagles Dare/Kelly’s Heroes (Brian G. Hutton, 1968/1970): A double bill of World War Two action from a director with little style, both starring Clint Eastwood. The first is a fairly dull, formulaic story of commandos parachuted into Occupied Europe on a suicide mission; the second, which holds up better, is a piece of cynical revisionism in which a renegade unit pushes through German lines to steal a stash of Nazi gold for themselves. The only really false note is Donald Sutherland’s anachronistic hippy tank commander.

One Dark Night (Tom McLoughlin, 1982): An unsung low-budget gem of early-’80s teen horror, with Meg Tilly spending a night in a mausoleum as an initiation into the mean girls’ clique; all hell breaks loose when a recently interred sinister occultist returns from the dead.

Jaws 2/Jaws 3D/Jaws: The Revenge (Jeannot Szwarc/Joe Alves/Joseph Sargent, 1978/1983/1987): Trying to turn box office hits into franchises is nothing new, and it’s not surprising that Universal should make the effort with the movie which launched summer blockbusters as a thing. Hence the sporadic release of three Jaws sequels over a nine-year period. The first of these basically repeated the structure, characters and plot points of the original, thereby illustrating just what Spielberg brought to Jaws; the retread is dull, unimaginative and never rises above B-movie pulp. The second sequel relocates from Amity Island to Sea World in Florida, where Chief Brody’s grown-up kids work; a great white lays siege to the theme park, the increasing silliness mitigated by some crackerjack poke-in-the-eye 3D effects. The third and last sequel opens with the younger Brody son, back in Amity and now a deputy himself, immediately getting eaten by a great white; his mother joins the remaining son in the Bahamas where strangely the shark follows her bent on … revenge! No wonder the series ended here. Despite a director with talent, it’s an embarrassing disaster.

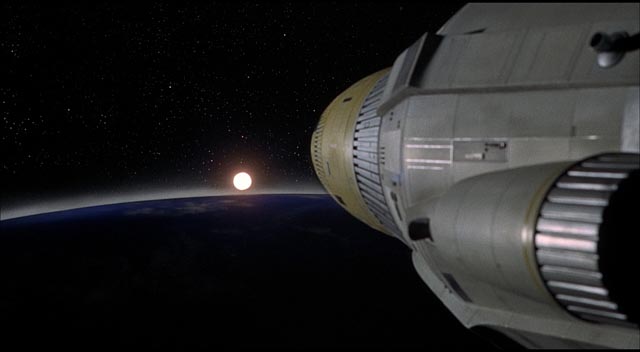

Journey to the Far Side of the Sun (Robert Parrish, 1969): Produced by Supermarionation master Gerry Anderson, this post-2001 sci-fi feature is intelligent if a little dull. When a new planet is discovered in Earth’s orbit but hidden exactly on the opposite side of the sun, a mission is launched. The Earth crew crashes on what turns out to be a mirror image world, where they are mistaken for an identical crew which was sent to explore Earth.

Police Squad!/The Naked Gun Trilogy (Jim Abrahams/David Zucker/Jerry Zucker/Peter Segal, 1982-94): The absurdist humour of Police Squad! and its three theatrical off-shoots holds up surprisingly well more than three decades after the original six episodes aired on television. A parody of earnest cop shows anchored by Lieutenant Frank Drebin’s (Leslie Nielsen) relentlessly literal responses to the people and events around him, the series and features provide the verbal equivalent of the Three Stooges’ physical slapstick.

Miami Vice (Michael Mann, 2006): Made two decades after the TV series debuted, Michael Mann’s Miami Vice feature seems strangely adrift in time; its slick neon-lit story of two completely implausible cops who get mixed up with international drug smugglers and various Federal agencies plays like a parody of Mann’s worst tendencies – all shiny surfaces and nothing to hold on to in terms of character or drama.

Inside Man (Spike Lee, 2006): Made the same year, Spike Lee’s hostage thriller is equally implausible, but a tad more entertaining. Clive Owen undertakes an obscurely complicated bank heist which turns into a cat-and-mouse contest with Denzel Washington’s police negotiator. Multiple characters drift in and out of the central plotline, but it never comes together in a satisfying way.

The Postman (Kevin Costner, 1997): I mentioned The Postman a few weeks back as a great and underrated movie, an opinion confirmed by subsequently re-watching it. The story of a reluctant hero helping to rebuild post-apocalyptic society along democratic, communal lines in the face of a fascist opportunist trying to impose order through violence, it’s rich in characters and has epic sweep; much of the derision which greeted its release was based on a cliched view of the incompetence of the existing postal service, ignoring the deeper idea that the ability to communicate among scattered settlements is actually the primary glue which binds people together into a larger society.

Ghost Rider/Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance (Mark Steven Johnson/Neveldine-Taylor, 2006/2012): The main drawback of these two Marvel movies is that Nicolas Cage becomes a CG character when he transforms into Satan’s soul-collector; so, although they’re entertaining enough, they fall short of the full-on Cage we get in something like Drive Angry (2011), to which this pair bear a passing resemblance.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (Sydney Pollack, 1969): Pollack’s fifth feature holds up really well as a depiction of desperation brought on by catastrophic economic collapse. An adaptation of Horace McCoy’s short, intense Depression-era novel, it gives us a group portrait of losers and dreamers who enter one of that period’s more bizarre inventions – the dance marathon, in which couples compete for weeks without sleep for a chance at an illusory monetary prize. One of the most exhausting movies ever made, with a great cast of veterans and (then)-newcomers.

Logan (James Mangold, 2017): I’m sick of comic book/superhero movies, but I got sucked in by all the positive reviews of Logan … should have known better. Whenever a superhero movie is treated as serious drama, it turns out to be a ponderous, pretentious bore (cf Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy) and this is no exception. Treating a sulky guy who can sprout hair and metal claws as a tragic hero of Shakespearean proportions would be inadvertently comedic, except this is so tediously dull that it can’t raise even a derisive laugh.

The Vikings (Richard Fleischer, 1958): One of journeyman Flesicher’s best movies, a vigorous historical epic in which the “hero” is not the good guy. Shot largely on location in a Norwegian fjord, it has a gritty physicality which puts it way ahead of studio-bound movies in the same genre.

The Frighteners (Peter Jackson, 1996): The movie that marked Jackson’s transition from quirky New Zealander to international mogul. With U.S. money supporting technical innovation, he made this ersatz-American comic ghost story with some style, but it was no longer rooted in the native soil which nurtured Bad Taste, Meet the Feebles, Dead Alive and Heavenly Creatures. The technical advances paved the way for the bloated, exhausting Lord of the Rings, King Kong, Hobbit products to come, but what made Jackson so distinctive was already disappearing. The artist was on his way to becoming a brand.

Salem’s Lot (Tobe Hooper, 1979): Although a television mini-series provided some breathing room for Stephen King’s big vampire tale, the limitations of what was permissible on a broadcast network reined in Hooper’s adaptation. There are some effective scenes, but in the end it leans more towards soap opera than all-out horror. Still, it’s a better King adaptation than –

Firestarter (Mark L. Lester, 1984): It’s always been a bit of a puzzle that the perennially popular Stephen King has fared so poorly so often when his work is adapted to the screen. Partly this is due to the fact that what makes so many of his books work so well is the way the stories are told rather than the stories themselves, which frequently use familiar, even cliched elements. When you take away the actual writing and merely use the plots, the results frequently end up as undistinguished B-movies … which is the case here, despite an impressive cast. It really needed a director with more flair than Mark L. Lester, whose best work remains Class of 1984 (1982).

Enemy (Denis Villeneuve, 2013): This adaptation of a José Saramago novel has become famous on YouTube for its unexpected final shot. How it gets to that moment is intermittently interesting, with Jake Gyllenhaal as a university lecturer who becomes unhinged when a double starts to take over his life. What this has to do with spiders is anyone’s guess.

Two Mules for Sister Sara (Don Siegel, 1970): The second of five collaborations between Siegel and star Clint Eastwood, this is one of many American attempts to reclaim the western from the Italian directors who had transformed the genre. Eastwood plays a variation of his Man With No Name who gets involved with a runaway nun (Shirley MacLaine) and the Mexican revolution. Efficiently directed, but it lacks the flair of so many genuine spaghetti westerns.

The Autopsy of Jane Doe (André Øvredal, 2016): A creepy little horror from the Norwegian director of Trollhunter (2010). Brian Cox is a coroner who’s passing along the secrets of the trade to his son Emile Hirsch and on this particular night they are brought the strangely undecayed body of a young woman which was found buried in the basement of a house where an unspeakable crime has been committed. As they begin to perform the autopsy, strange things start to happen.

Kong: Skull Island (Jordan Vogt-Roberts, 2017): When it comes to King Kong, I’m a strict originalist; the power and poetry of the 1933 movie remains unsurpassed and none of the remakes, pseudo-sequels and imitations have managed to grasp what makes it so special. This one is no exception, though in its way it’s mildly entertaining and it does make an effort to instill some personality into its CG ape. But in conception it’s nothing more than a generic action-fantasy.

The Lair of the White Worm (Ken Russell, 1988): One of Russell’s most entertaining late films, an outrageously comic adaptation of a lesser novel by Bram Stoker, rooted in English folk legend. The vampire here, Lady Sylvia Marsh (Amanda Donohoe), is something like a projection of a great snake demon which lives deep beneath the English countryside; she’s opposed by a young archaeologist (Peter Capaldi, best known for The Thick of It and Doctor Who) and the plucky Mary Trent (Sammi Davis).

Nothing (Vincenzo Natali, 2003): Not sure why it took me so long to catch up with this, Vincenzo Natali’s third feature, as I quite liked his imaginative low-budget debut, Cube (1997). Nothing is a strange, original, unclassifiable movie about a pair of slacker roommates who, when their lives get swamped by problems, somehow wish the world away. They end up with their ramshackle house in the middle of an infinite empty white space where their irritation with each other causes them to progressively erase what’s left. It’s funny, engaging and quite Gilliamesque (probably not purely by coincidence, Natali’s next film was a documentary about Terry Gilliam and the making of his underappreciated masterpiece Tideland [2005]).

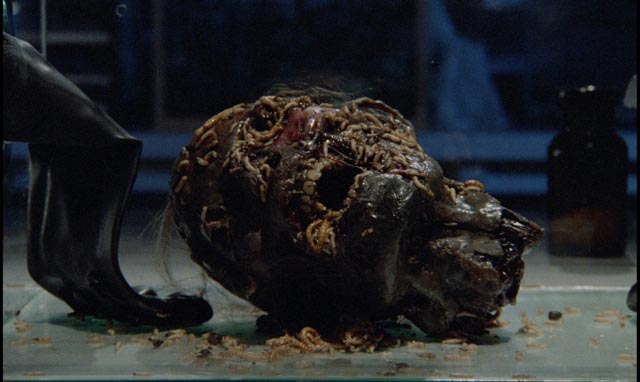

Phenomena (Dario Argento, 1985): Argento had an exceptional creative run from his 1970 debut with Bird With the Crystal Plumage to 1987’s Opera. With Phenomena (1985), he made a deliberate attempt to boost his international audience by making his first fully English-language feature (the previous films were typically Italian, with multi-lingual casts who were dubbed for different markets). The awkwardness of this movie can be largely attributed to Argento’s discomfort with directing his cast in English, but it’s still strangely engaging because of the sheer weirdness of its story, which centres on an adolescent girl who can commune with and control insects and reaches a climax involving a vengeful, razor-wielding chimpanzee.

The Lost Boys (Joel Schumacher, 1987): Made the same year as Kathryn Bigelow’s gritty Near Dark, this was the glossy, kid-friendly vampire movie – not surprising given that the title is a reference to Peter Pan. It is similar in tone to Buffy the Vampire Slayer (the original movie was made five years after this), though without the layers of wit. Still, its mix of blood-sucking and teen angst works quite well; the young cast is good and Michael Chapman’s nighttime photography is pretty in that glossy Schumacher way.

Frank (Lenny Abrahamson, 2014): Frank (Michael Fassbender) is a socially dysfunctional musician who wears a giant full-head mask, both on stage and in life. Jon (Domhnall Gleeson) is a would-be musician and hopeful song-writer who, purely by accident, finds himself playing keyboards in Frank’s band. I’m not sure the film is at all successful (I could never figure out what I was supposed to think of the band’s music – is it brilliantly avant garde, or just pretentious nonsense?), but it’s very entertaining and, in its final scene, genuinely moving. Seeing it made me seek out writer Jon Ronson’s memoir about his time with the real-life Frank Sidebottom, and that story turned out to be more interesting than the highly fictionalized version in the film.

Shin Godzilla (Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, 2016): The latest Japanese installment of the perennial Godzilla saga updates the metaphorical monster. Once a symbol of the destruction caused by nuclear weapons, the big lizard here represents a post-Fukushima threat. Tokyo Bay is hit by a sub-surface disturbance which is revealed to be the emergence of a giant monster. In its first incarnation, it has the slinky form of a Chinese dragon, but as it makes its way to the centre of the city, it evolves into the more familiar radioactive dinosaur. The big G spends a lot of time just standing motionless as he recharges his radioactive battery, while the film spends a lot of time in committee meetings as politicians and scientists argue about how to deal with the threat. It’s the most bureaucratically-focused Kaiju movie ever, and strangely entertaining for that.

Colossal (Nacho Vigalondo, 2016): After his fiercely original debut feature, Timecrimes (2007), Spanish director Vigalondo has been exploring various different genre possibilities with uneven success. I’m still not sure what to make of his latest feature. The central narrative – a woman returns to her hometown to figure out her life and gets involved with an old highschool friend who gradually reveals a dark, embittered side – is an effectively bleak relationship comedy-drama. And when that relationship becomes externalized in the form of Kaiju monsters trashing Seoul, it’s certainly visually effective. But the monster show tends to distract from the personal story rather than elaborate on it – the literalness of film works against such big metaphors. Nonetheless, it’s quite entertaining thanks to the fine cast and some comedic Kaiju action.

Alien: Covenant (Ridley Scott, 2017): Could Scott make a worse movie than Prometheus? It’s a toss-up. Instead of the incoherent pretension of that movie, in Covenant he decided to make a weak and unnecessary Alien retread. This movie has numerous echoes of his groundbreaking original, with none of the style. It plays like one of those ’80s quickie Alien rip-offs, dutifully churning out predictable scares and killing off its cardboard characters one by one.

Willow Creek (Bobcat Goldthwait, 2013): This was unexpected. Coming late to the found-footage-horror genre, comedian Bobcat Goldthwait crafts a slow-burn little gem about an engaged couple who head into California’s Bigfoot country to shoot their own doc about the locals’ feelings about the area’s notoriety – it was here that Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin shot their famous shaky home movie of Bigfoot in 1967 (one of the first “real” instances of the genre which flowered after The Blair Witch Project [1999]). They encounter real locals who obsess about the legendary creature – and some who resent their interest – and eventually get lost, threatened by noises and shadowy figures in the woods at night. Somehow Goldthwait makes the familiar elements fresh and effective and genuinely creepy. There’s a terrific uninterrupted 18-minute take of the couple stuck in their tent in the middle of the night as something prowls and threatens from outside.

The International (Tom Tykwer, 2009): Tykwer was once a director of heady existential puzzles – Winter Sleepers, The Princess and the Warrior, and his break-out hit Run Lola Run – but once he became famous, something changed in his work and it became less distinctively personal. He shot an unfilmed Kieslowski script (Heaven), adapted the literary potboiler Perfume, teamed with the Wachowskis to tackle David Mitchell’s complex narrative puzzle-box Cloud Atlas – and directed this slick multinational thriller which tries hard to make corrupt bankers into exciting villains. There are chases and killings, but in the end it feels like an earnest educational effort about what’s wrong with international finance.

Deliver Us From Evil/The Exorcism of Emily Rose (Scott Derrickson, 2014/2005): It seems that Derrickson believes in the reality of evil; this pair of movies about possession claim to be “based on true stories”. Although there’s something inherently ridiculous in the Catholic mumbo-jumbo surrounding possession stories, I quite enjoy them when they’re well-told and Derrickson does tell them effectively. Deliver is an enjoyable supernatural thriller about a New York cop who teams up with a renegade South American priest to combat an outbreak of possessions in the city, while Emily Rose is about an agnostic lawyer hired to defend a priest against criminal charges when the possessed girl under his care dies. Both are definitely better than Derrickson’s misguided remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still (2008).

Untraceable (Gregory Hoblit, 2008): Coming out of a career in television cop shows, Hoblit made several effective thrillers in the late ’90s (Primal Fear, Fallen, Frequency), but this one is too nasty to be entertaining. Like so many movies that tackle the evils of the Internet, it finds itself sinking into the more unpleasant side of human nature – here, a serial killer who live-streams his crimes, speeding the protracted murders up as more people log in to watch. Diane Lane is a cybercrimes cop working to trace the source of the feed before more people die … and we in the audience get to enjoy the sadistic spectacle of each killing just like the callous people the movie is condemning.

Gangs of Wasseypur (Anurag Kashyap, 2012): At five-and-a-half hours, this epic strives to be the Godfather of India. Covering decades and generations in the life of a criminal family, it’s packed with incident, but I’m afraid I had a hard time following all the characters and their complex interconnections – maybe the effort of reading subtitles over such a long stretch simply exhausted my brain. It’s colourful, violent and unexpectedly gritty, and perhaps most interesting in its use of Bollywood musical tropes. Instead of periodically interrupting things to give the characters a chance to sing their feelings, the songs are embedded in the lives of those characters as they are in real life – that is, the characters use music to shape the way they see themselves and their circumstances, borrowing from the movies they’ve seen to idealize their own existence.

Night of the Creeps (Fred Dekker, 1986): Dekker pays homage to ’50s sci-fi and horror by way of ’80s teen comedies as alien parasites which landed on Earth decades ago get loose and infect a bunch of college kids. He manages to blend the various elements (and tones) quite well, thanks in part to a good cast, and there are effective gross-out moments, but in the end it plays more to the comedy than to the horror, rendering it more harmless than it needed to be.

Jamaica Inn (Alfred Hitchcock, 1939): Hitchcock ended his remarkable British period with this Daphne du Maurier adaptation, before beginning his illustrious American period with another du Maurier adaptation. In both cases, he was somewhat at the mercy of his producer – but the overbearing David O. Selznick was more inclined to trust the director on Rebecca, while producer-star Charles Laughton seized control of Jamaica Inn. Although Hitchcock wasn’t happy with the results – and in many ways, this is a clumsy film – it’s a beautifully designed and atmospherically shot period piece, with an interesting cast (Laughton insists on dominating, but he’s surrounded by good actors) and some impressive set-pieces. It’s actually better than its reputation and no doubt appears worse than it is only because it’s situated between the great British films of the ’30s and the ones which followed in Hollywood over the next three decades.

Atomic Blonde (David Leitch, 2017): This got a very positive response from critics and audiences, but it was one of the worst movies I’ve seen recently. Outside of the brutal fight scenes, it’s facile and incoherent, its multiple climactic plot twists making nonsense of an already poorly told story.

Death Line (Gary Sherman, 1972): A great ’70s mix of horror and humour about a snarky Scotland Yard detective (Donald Pleasance) investigating disappearances in the London Underground which lead to a pathetic family of cannibals living beneath the city.

The Planet of the Apes reboot trilogy: As attempts to reboot popular franchises go, the new Planet of the Apes trilogy stands as one of the best. These movies have been made by people who obviously like and respect the original series (five movies of declining quality released between 1968 and 1973), unlike the dreadful Tim Burton attempt in 2001. Rupert Wyatt’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) is an origin story, which plausibly explains the appearance of smart, talking apes as a result of medical experiments; those same experiments also trigger the beginnings of human decline which will result in the loss of language and the ceding of dominion to the apes. It’s also pleasingly laced with peripheral details which link it to the events of the original film. I didn’t like the second movie as much when I saw it in a theatre – and as a result didn’t go to see the third at all – but watching all three in succession on disk, I now appreciate both Dawn of (2014) and War for (2017) – both directed by Matt Reeves – as a well-thought-out epic about the self-destructive paranoid violence of our species, with the apes, although riven by internal conflicts (largely rooted in mistreatment by humans), showing the possibility of a better society. If the final film ends in a place which seems to deny the world depicted in the original film – an oppressive, theocratic ape society which brutally enslaves mute humanity – those intra-ape conflicts could perhaps evolve in that direction, instilling the hopeful ending of War with a melancholy suggestion of the fragility of peace and decency. By the way, although Andy Sirkis, as the apes’ leader Caesar, gets all the accolades, by the third film his dour determination results in something of a one-note performance and the movie is handily stolen from him by Karin Konoval and Steve Zahn as, respectively, the soulful Orang Maurice and the jittery chimp Bad Ape; they end up being the main reason we care about the fate of the apes.

Television

Westworld: Season 1 (Various, 2016): This reworking of Michael Crichton’s inventive low budget feature has spectacular production values and an amazing cast. The story is pretty convoluted (you only realize late in the season that it’s actually taking place in two timelines), but I still felt the idea was not as well-developed as it should have been. Although it’s set in a high-tech theme park, there are very few “customer” characters as it focuses on the behind-the-scenes technicians and managers and a large group of the “worker” androids. Everything seems to be designed for the androids’ narrative lines rather than the guest experience. Still, it does well with the increasing consciousness of the machines as they live and die repeatedly, becoming more complicated as they gain awareness of their brutal enslavement.

South Park 20 (Trey Parker and Matt Stone, 2017): The foul-mouthed animated series remains very funny and sharply observant after a remarkable twenty seasons.

Fear the Walking Dead: Season 2 (Various, 2016): I got tired of The Walking Dead after three seasons, but find the spin-off more interesting … not sure why, other than the characters seem less irritating.

Orphan Black: Season 5 (John Fawcett et al., 2017): One of the best sci-fi series ever made, and it’s Canadian! Written and directed with intelligence, what raises this complex thriller about clones is the remarkable multiple performance by Tatiana Maslany who not only imbues the many clones with quirky and distinctive personalities, but also manages to play many scenes in which she interacts with herself flawlessly. While this is executed with impressive technical skill by the crew, it’s given layered emotional life by Maslany’s seemingly effortless acting; you completely forget that you’re watching a trick performed by one person. The fifth and final season brings the story to a satisfying close – unlike so many series which drag on and flounder at the end, you get a clear sense that this was planned out from the beginning.

*

As I mentioned above, even this long list doesn’t represent everything I watched but didn’t review over the past three months. Below are twenty more titles I just haven’t had time for because of my full-time job and an excessive viewing habit. Many of these are more deserving of comment than some of the ones I’ve included above, and the foolishly optimistic part of me still hopes to write about them in more depth at some point in the not-too-distant future:

The Exterminator (James Glickenhaus, 1980)

Ripper Street: Series Five (Various, 2016)

The Ghoul (Gareth Tunley, 2016)

The Barber (Basel Owies, 2014)

Dreamscape (Joseph Ruben, 1984)

The Stendahl Syndrome (Dario Argento, 1996)

Wonder Woman (Patty Jenkins, 2017)

Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971)

Snapshot (Simon Wincer, 1979)

Dead Again in Tombstone (Roel Reiné, 2017)

It Stains the Sands Red (Colin Minihan, 2016)

Night of the Living Dorks (Matthias Dinter, 2004)

It Comes at Night (Trey Edward Shults, 2017)

Green Lantern (Martin Campbell, 2011)

The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967)

The Dirty Dozen: Next Mission (Andrew V. McLaglen, 1985)

Airport (George Seaton, 1970)

Peyton Place (Mark Robson, 1957)

Kung Fu Hustle (Stephen Chow, 2004)

Comments