Barbet Schroeder’s General Idi Amin Dada (1974): Criterion Blu-ray review

Barbet Schroeder’s General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait (1974) is a fascinating yet troubling film. Shot about a third of the way through Amin’s reign as dictator of Uganda (from 1971 to 1979), it was made at a time when the West largely viewed him as a buffoon, although the violence he perpetrated to consolidate and hold on to power was already becoming apparent. In fact, the film opens with footage of an execution and a voice-over tells us that Amin is responsible for the deaths of perhaps thousands. But, as the title indicates, what we see is Amin as he wants to present himself.

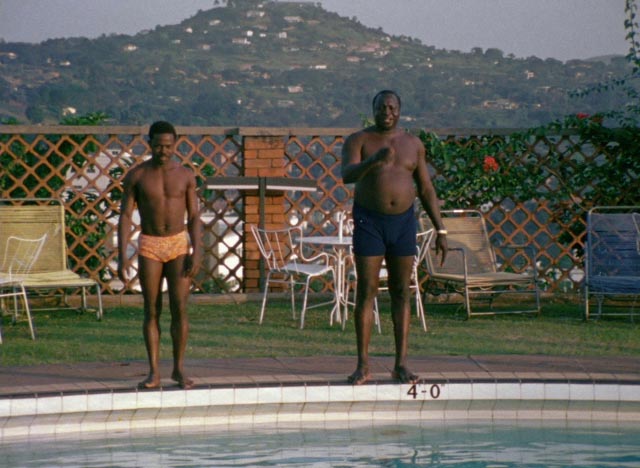

With money from French television, Schroeder and his small crew (including cinematographer Nestor Almendros) flew to Uganda and simply asked if they could film the dictator. Like many a self-aggrandizing despot, Amin was flattered by the attention and for the next two weeks Schroeder shot various (frequently staged) events whose purpose was to show Amin as a great statesman and representative of post-colonial Africa.

A huge (6-foot-4, 240lb) man, he comes across as gregarious and even charming. He seems to have a sense of humour and an engaging laugh. Early in the film, he takes the crew on a river tour, pointing out the abundant wildlife, greeting an elephant and talking to some very large crocodiles. These images, and some panoramic views of Kampala which suggest a modern, vibrant city, are undercut by references to the expulsion of the country’s Asian community, which comprised much of the mercantile class. These immigrants had been brought in by the British to manage the economy, a fact which generated much resentment. But despite Uganda being a resource-rich country, the expulsion caused economic turmoil and closer views of the city’s streets show many stores to be almost empty.

Schroeder can occasionally be heard prompting with off-screen questions, asking about Amin’s assertion that Hitler had not killed enough Jews (Amin laughs and says there’s no point looking at the past, we need to concentrate on the future). Although he and other members of the Ugandan military had received training in Israel, he switched his allegiance to the Arab countries and became an outspoken foe of Israel, saying he would welcome anti-Israeli terrorists (leading a couple of years later to the incident of a hijacked airliner taking refuge at the capital’s airport which ended with the raid on Entebbe to free the hostages).

Amin touts the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (the notorious anti-Semitic fabrication of the pre-revolutionary Russian secret service) and talks about waging war against Israel. This leads to one of the film’s oddest sequences, as Amin leads a mock attack on what he designates the Golan Heights, a scrubby patch of ground which his men “storm” with a handful of armoured vehicles backed up by two jet fighters. His army here seems to consist of only a few dozen men, and yet he proudly claims victory. Here, he has staged his own parody of a mad king’s delusion of military conquest.

The film is full of parades and displays of supposed military might (paratroops are trained on a makeshift playground slide without any actual equipment). A visit to a small town is staged in which the local population is rounded up and coached to cheer the arriving leader; his helicopter flies in, blowing up thick clouds of dust which make the crowd scatter, a natural metaphor for the fragility of the supposed love with which his people view him.

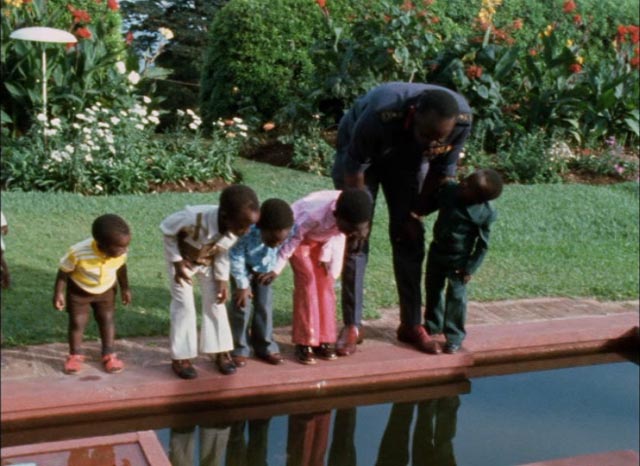

At another point, Amin cheerfully plays an accordion, backed up by a small band, while people dance around the ballroom. It’s a song he wrote himself; in fact, the film’s score is credited to Amin himself. He’s interviewed in a garden surrounded by some of his eighteen children, but his wives don’t appear on camera because he was already starting to dispose of them. That absence, not overtly referred to in the film, reflects a critical limitation of the documentary – that a full interpretation of what’s being shown requires outside knowledge. What we see on screen is largely a self-serving portrait of a man who conceals his monstrousness behind an illusive display of purportedly revealing honesty. At a superficial glance, he might still be perceived as a joke, an egotistical clown.

And yet there are two sequences where the darkness behind that facade does show through. In the first, Amin stages a meeting with his cabinet for the camera. Seated around a long table, these men in suits and uniforms listen dutifully as he harangues them; they look down sheepishly, taking notes. He insists that their primary task is to encourage the people to love their leaders … to love him. He berates the foreign minister for failing to gain other countries’ respect and love. And here, in a rare intrusion, Schroeder interrupts the scene and a voice-over informs us that ten days later the minister’s body would be found floating in the Nile and he would be replaced by Princess Elizabeth Bagaya, who would go on to serve in the role for most of 1974. The sheepishness of the cabinet members as they listen to him takes on a new and sharper meaning, particularly in light of the vague generalities with which he exhorts them – we get a sense that it will never be possible to know what will either please or displease him.

With that in mind, the film ends with its most chilling scene. In a lecture hall where Amin has been addressing a group of doctors, a member of the audience gets up to respond – immediately treading on uncertain ground when he refers to the president of the medical association: no one but Amin can be referred to as president. Amin chuckles, but the tension in the room is palpable and the camera holds tightly on the dictator’s face as the doctor continues to pursue the point he was trying to make. There is tension and impatience on Amin’s features and for the first time we get a clear, unequivocal sense of just how dangerous he is, how easy it would be the say a wrong word and end up dead.

Only in the film’s final moments does Schroeder raise a critical point; a concluding voice-over asks whether, given centuries of colonial oppression, Amin isn’t simply a “deformed image of ourselves”. But that thought, tossed in at the last minute, within the film itself provides little counterweight to the impression that this self-proclaimed revolutionary leader of the new post-colonial Africa is, for all his violent crimes, still at his core an absurd clown. When it was first released in France, a reporter for the International Herald Tribune called it “the funniest film in town” and said that if it was fiction it would be “acclaimed as a comic masterpiece”.

By restricting himself to what Amin chose to show him, without including any broader contextual material, it’s difficult not to sense a touch of condescension on Schroeder’s part, a feeling of sophisticated Europeans looking down on Africans trying to play a game which they don’t fully comprehend. Schroeder has asserted that his theme is “anti-power”, but the particular case he has chosen to use to examine that theme is fraught with perhaps unintended consequences which circle around issues of race. Whether Schroeder intended it or not, the film at least partially reflects the prevailing attitude of the time which saw Amin, despite his brutal crimes, as something of a joke specifically because he was a poorly educated Black man who claimed for himself the stature of a statesman.

Some of those issues are illustrated on Criterion’s new Blu-ray edition in a brief interview with author Andrew Rice, who provides some historical context. In particular he points out that one of the most damaging consequences of colonialism was the practice of Europeans to carve out countries regardless of the inherent nature of the various population groups contained within these artificial borders. Ignoring complex histories of tribal interrelations guaranteed that none of these countries once liberated would have coherent internal social structures, leading almost inevitably to the rise of dictators who would use force to hold disparate groups together – and eliminate rival groups. In this, perhaps Amin was not a “deformed image of ourselves” but rather a creation of European arrogance.

If the disk has one large flaw, it’s that it doesn’t include an African perspective on Amin or on the film itself.

The disk

The Blu-ray features a 2K scan from the 16mm camera original. Shot on reversal stock, as opposed to negative, the image reflects the format, with pronounced grain and quite vibrant colours. Sound is clear, though again it reflects the circumstances of the filming, with scenes caught on the fly in less than optimal conditions.

The supplements

In addition to the brief but informative interview with Andrew Rice (15:49), there are two interviews with director Schroeder, from 2001 (26:43) and 2017 (12:35). The more recent one is essentially redundant as Schroeder repeats almost word for word what he said in the earlier interview. He provides some interesting, and disturbing, background details about Amin’s violence, which is naturally not presented in the film because Amin himself controlled the content. Questions are raised (but not resolved) about the implications of remaining a disinterested documentary observer while the subject of the film was actively committing murders during the period of filming. Schroeder explains that his aim was to have Amin present himself as a caricature of a political leader to stand in for all politicians who are deformed by their power.

The booklet essay by J. Hoberman emphasizes the performative aspect of the film, that this “self-portrait” has been staged by its subject to present the image he wants the world to see – as a major player, not only in Africa but on the world stage. But Hoberman strains somewhat to suggest parallels with the self-presentation (and buffoonery) of the current U.S. president

Comments