Hammer Horror on Blu-ray

Hammer Films are, of course, best known for launching the modern era of horror with their late ’50s colour reworkings of the Universal classics from the ’30s, beginning with Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958). These movies, colourful, somewhat perverse for the time, and more graphic than earlier films in the genre, inspired Roger Corman’s Poe cycle at American-International as well as the even more violent and perverse Gothic horrors from Italy by Mario Bava, Antonio Margheriti and others.

Perhaps if I had seen these films as they first came out they would have had a powerful impact on me – but as a child in England I was barred from seeing them. Although in the States they were considered fit for kids’ matinees, in England they were slapped with an “X” rating – adults only (applied there for violence and horror rather than, as in the States, for sex). I saw the studio’s later, less influential releases in my teens as they were released in theatres, but by then Hammer’s approach to horror was already out-of-date. I came to the earlier, more important films later, in the late ’60s and early ’70s, on television – pan-and-scanned and in black-and-white. It was really only with the advent of home video that I finally got to see many of them in colour, but by then there was little chance of them having much impact.

The things which shocked and disgusted the censors at the time, and which made the films popular with audiences – like Baron Frankenstein cutting organs out of a corpse and keeping them alive in a fish tank; or those same organs being spilled out onto the floor by an irate priest – lack a visceral impact when seen today in the context of all that has come since. While it is possible to understand those shocks on an intellectual level, we can no longer feel them the way a contemporary audience did. For us, they seem more like the offenses of naughty boys looking for a reaction by poking a finger in propriety’s eye.

Which possibly explains why the Gothic horrors are not my favourite Hammers. I prefer the Quatermass trilogy (Val Guest, 1955 and 1957; Roy Ward Baker, 1967); Joseph Losey’s The Damned (aka These Are the Damned, 1963); Guest’s war films The Camp on Blood Island (1958) and Yesterday’s Enemy (1959); and the studio’s two best psycho-thrillers, Seth Holt’s Taste of Fear (1961) and Silvio Narizzano’s Fanatic (aka Die! Die! My Darling!, 1965). In these, the horrors are more firmly rooted in a recognizable reality, rather than distanced by colourful costume play. This same sense of reality is also present in Guest’s gritty police noir Hell Is a City (1960) and a small gem like Quentin Lawrence’s Cash on Demand (1961), where tension comes from psychological torment rather than graphic physical effects. Among the studio’s period films, my personal favourite is Don Sharp’s non-horror The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964), a reworking of Cavalcanti’s wartime classic Went the Day Well? (1942) in Elizabethan dress.

But that said, I do still enjoy the more canonical Gothic horrors, despite the fact that they’re not particularly scary. In fact, there’s something almost cosy about them. They’re like the comfort-food of horror, filled with familiar character actors, over-stuffed set design, and shock moments which quickly become predictably familiar and thus reassuring. A friend recently watched The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula for the first time and expressed some surprise and disappointment because he found them rather crudely made and not in the least scary. I couldn’t disagree, and yet I still find these movies entertaining despite their seeming weaknesses.

Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection (Various, 1959-64)

Which is why I recently picked up a sale copy of Universal’s Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection on Blu-ray (an upgrade from the original DVD set released in 2005). There have been numerous on-line complaints about incorrect aspect-ratios, and at times the transfers do feel a bit cramped, indicating that Universal has forced a wider frame on films which should have probably been transferred at 1.66:1 instead of 1.85:1 or 2.0:1; but the visual quality is generally quite high, with rich, saturated colours. The most problematic transfer is Night Creatures (aka Captain Clegg, 1962), with a number of optical effects revealed as soft and overly grainy.

The biggest disappointment of the set, however, is the complete absence of any supplements, indicating that Universal sees these films as largely disposable properties despite their committed and highly vocal fan base. Four of these films have been released in a set in England by Final Cut Entertainment, packed with extras including documentaries and commentaries, while quite a few other titles have received stand-alone releases in region B with supporting supplements. I suppose it’s not surprising that British companies have more respect for these quintessentially British properties. Nonetheless, I did spend several pleasant evenings watching the eight movies in the set.

The selection of titles seems kind of random, but it does contain two of the studio’s best non-Dracula vampire movies, Terence Fisher’s Brides of Dracula (1960) – despite the title’s attempt to link it to the original 1958 film, the only connection is Peter Cushing reprising his role as Van Helsing – and Don Sharp’s The Kiss of the Vampire (1963), which offers vampires as a cult which presages the Satanists of Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out (1968). In Brides, Marianne (Yvonne Monlaur), a young woman on her way to a teaching position at a girls’ school, is sidetracked by the Baroness Meinster (Martita Hunt), a mother torn by the fact that her son is an undead monster for whom she provides victims. Marianne is tricked by the son (David Peel) into releasing him and he escapes and starts to prey on the school’s girls. Van Helsing luckily shows up to deal with the problem.

In Kiss of the Vampire, when a honeymooning couple, Gerald Harcourt (Edward de Souza) and his wife Marianne (Jennifer Daniel), are stranded in the mountains, they are invited to the local chateau where the leader of a vampire cult and his children scheme to convert the young wife to their perverse way of (un-)life. To this end, they drug Gerald at a masked ball; when he wakes the next day with a massive hangover they deny any knowledge of Marianne (a variation on Terence Fisher’s So Long at the Fair [1950]) and kick him out. With the help of the tormented Doctor Zimmer (Clifford Evans), whose own daughter was “converted” by the decadent fiends, Gerald manages to defeat the cult and rescue Marianne in a finale which edges towards inadvertent comedy with a surfeit of rubber bats attacking the vampires.

Fisher’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) is, strangely, the studio’s only foray into lycanthropy. Based on Guy Endore’s 1933 novel The Werewolf of Paris, like the Universal Wolf Man movies it treats the monster sympathetically as a decent man cursed with an affliction against which he struggles – in this case, since childhood. The film spends its first half filling in Leon Corledo’s background: his mother is a mute servant girl (Yvonne Romain) in the castle of the Marques Siniestro (Anthony Dawson). This sadistic nobleman, after humiliating a beggar (Richard Wordsworth, Victor Caroon in Val Guest’s The Quatermass Xperiment) at his wedding feast, throws the man into a dungeon and forgets about him. Years later, after the girl rejects the Marques’ sexual advances, she too is thrown into the dungeon where the now-mad beggar rapes her. Leon is the child who results, his unholy birth substituting for the traditional infection by werewolf bite. The curse manifests from anger rather than the inexorable pull of the full moon and Leon’s attempts to live a normal life are thwarted by the cruelty of the society around him.

The film has a leisurely pace, taking a long time to get to the actual werewolf, and it lacks the poetic tone of George Waggner’s The Wolf Man (1941), but the Spanish period setting keeps it engaging and the cast has many recognizable faces – Michael Ripper, Warren Mitchell, Peter Sallis, Clifford Evans – who provide a pleasing sense of familiarity. But mostly it’s notable for the first lead performance by Oliver Reed, who brings a degree of conviction and intensity to Leon which adds some dramatic heft to the film. Only twenty-three at the time, Reed already displays the larger-than-life screen presence which marked his career for the next forty years.

Reed also shows up in Night Creatures (aka Captain Clegg, 1962), directed by Peter Graham Scott, who had a lengthy career mostly in television. The story of a small village, most of whose inhabitants are involved in smuggling, it has obvious echoes of both Jamaica Inn, the Daphne DuMaurier novel filmed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1939, and Disney’s Dr. Syn, the Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, directed by James Neilsen and adapted from a series of novels written by Russell Thorndike between 1915 and 1944. The village’s illegal operations are run by the reformed pirate Captain Clegg, who uses the profits for the good of the community; but it’s still illegal and a unit of the King’s Men under the command of Captain Collier (Patrick Allen) arrive to put a stop to their crimes against the Crown. This outside pressure combines with internal conflicts in the gang to expose Clegg, who manages to redeem himself through a last-minute sacrifice.

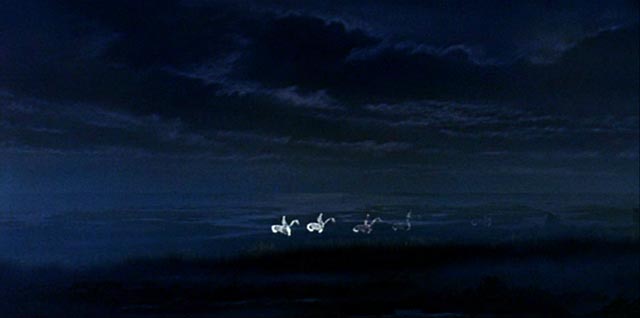

Although the movie has a typically reliable Hammer cast – in addition to Reed, who appears as the Squire’s son who moonlights as a collaborator of the smugglers, Peter Cushing provides his usual authority, along with support from Michael Ripper, David Lodge, Jack MacGowran and Peter Halliday, while Allen adds some dash as Collier without making him a villain – director Scott lacks the flair of other Hammer directors (Fisher, Sharp, John Gilling, even Freddie Francis) and the film plods rather than romps through its story, further let down by weak optical effects (the ghostly Marsh Phantoms, a fake supernatural phenomenon concocted by the smugglers to warn off anyone who might get in the way of their work, look cheap and ineffective).

One of the surprises of watching this collection was finding that Terence Fisher’s The Phantom of the Opera (1962) is better than I remembered. I always found this retelling of the familiar Gaston Leroux tale kind of dull, but this time it seemed quite engaging. It helps if you look at the story as a romance rather than horror. The script by producer Anthony Hinds (writing as John Elder) keeps the narrative to its simple central idea – Christine (Heather Sears), a talented young singer, draws the attention of the Phantom, a disfigured composer who lives in the sewers beneath the opera house; he determines to shape her into a great singer who can do justice to his work which was stolen by the vile impresario who is now staging it. Erik, the Phantom (Herbert Lom), is a sympathetic character, while Lord Ambrose D’Arcy (Michael Gough at his best) is an excellent, hissable villain.

Phantom lacks a lot of the big set-pieces associated with other versions of the story – the Phantom barely haunts the theatre here – but the slight story moves along nicely and, as usual, the cast is strong. To some degree, this romance seems better suited to Fisher’s personality than the grislier Frankenstein and Dracula projects, and the results, though perhaps a minor addition to the Phantom’s career, make for one of his most satisfying films.

Freddie Francis, like Fisher, contributes three films to the set. A superb cinematographer, Francis was not exactly an inspired director, his work generally competent, but often rather dull. The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) came six years after Hammer’s second go at the story, Fisher’s The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), and writer Jimmy Sangster didn’t even bother to follow on from the earlier films. Here, after having his work ruined by a local priest, the Baron (Peter Cushing) and his young (non-hunchbacked) assistant Hans (Sandor Elès) escape back to Karlstaad to resume work in the Baron’s old home laboratory. Not very plausibly, Frankenstein is shocked to discover that in the intervening ten years the place has been looted and trashed. He foolishly exposes himself by throwing a fit in the local tavern when he sees the Bergomeister wearing one of his old rings and demands the official’s arrest. Not the best way to lay low and pursue heinous experiments.

Having discovered his old creature frozen in ice inside a cave, Frankenstein and Hans set about reanimating him; in order to kick start the damaged brain, the Baron makes use of the talents of Zoltan (Peter Woodthorpe), a carnival hypnotist … unfortunately, the bitter performer gains control of the creature and uses him to get revenge on various town officials, bringing down the wrath of the populace.

It’s all rather perfunctory, with the plot moved along by a series of stupid decisions on Frankenstein’s part; there’s an air of tired duty, with everyone going through the motions of adding one more chapter to a series purely for commercial reasons. It isn’t helped by the crude design of the creature, which looks as if it might have been whipped up by an enthusiastic 14-year-old for a home-made Halloween costume.

Francis’ other two contributions to the set are better than this. Paranoiac (1963) and Nightmare (1964), both written by Jimmy Sangster, belong to Hammer’s post-Psycho series of horror-suspense movies, and both bear a closer resemblance to the films of William Castle than to Hitchcock’s seminal masterpiece. Both centre on a neurotic young woman whose family circumstances make her fear for her own sanity.

Paranoiac stars Janette Scott as Eleanor Ashby, whose parents died in a plane crash eleven years ago, and whose beloved brother Tony apparently committed suicide three years later by throwing himself off a cliff into the sea. Permanently distraught, Eleanor longs to join Tony and eventually throws herself off the same cliff, only to be rescued by a man who claims to be Tony (Alexander Davion); he says that he actually ran off to get away from the tragic family. Eleanor accepts him immediately, but her other brother, Simon (Oliver Reed), and their guardian Aunt Harriet (Sheila Burrell) suspect he’s an imposter. While they and the lawyer who manages the family trust try to determine the truth, Eleanor finds herself falling in love with Tony, being driven to distraction by the incestuous implications of her feelings; and Simon slips dangerously into alcohol-fueled instability. The influence of Psycho is most evident in the climactic revelation of what really happened to Tony and the unhealthy connection between Simon and Aunt Harriett.

In Nightmare, Jenny Linden is Janet, a girl driven to distraction by – well, nightmares. As her behaviour becomes more disruptive at boarding school, she is sent home. Not the most helpful thing, given that this is the house where she walked in six years earlier to find her insane mother standing over the body of her father with a bloody knife in her hand. Nonetheless, she’s looking forward to seeing her guardian Henry Baxter (David Knight) on whom she has a crush. Despite being under the care of a nurse companion, Grace Maddox (Moira Redmond), Janet begins to see disturbing things around the house, seeming to justify her fear that she’s inherited her mother’s madness. Naturally it turns out that someone is gaslighting her, trying to push her over the edge so that she’ll commit an act of violence for that someone’s benefit. The film’s big twist comes after that act of violence when someone else starts gaslighting the original gaslighters …

Both of these movies, nicely shot in widescreen black-and-white (by Arthur Grant and John Wilcox respectively), work well enough on a plot level, although the overly emotional neuroses of their heroines gets a bit grating at times, and neither has the kind of cheesy glee that marks so much of William Castle’s work; Francis essentially just keeps things going, working up some creepy atmosphere to add flavour to the contrived plots, and as always with Hammer, there’s good work from the casts.

*

The Hound of the Baskervilles (Terence Fisher, 1959)

Arrow Films displays greater respect for Hammer than Universal in their Blu-ray release of Terence Fisher’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959). The transfer is as good as those on the Universal disks, but the film is supplemented with a commentary and several informative featurettes (the region A release from Twilight Time, which I haven’t seen, offers two different commentaries and repeats some of the featurettes). Hammer predictably emphasizes the horror elements of Conan Doyle’s most famous Sherlock Holmes novel, particularly in the extended prologue giving the background of the legend about a demonic hound whose appearance on Dartmoor presages death in the Baskerville family – it originally appeared hundreds of years earlier when a sadistic Baskerville ancestor brutalizes a servant and tries to rape the man’s daughter.

In the film’s present, after the death of the latest lord of Baskerville Hall, the last remaining descendant arrives from overseas to take up residence in the gloomy manor, but is warned about the curse and encouraged to go away again. With Holmes (Peter Cushing) called in to investigate, Sir Henry insists on going down to Dartmoor anyway. Conan Doyle’s story is unusual in the canon for having Holmes disappear for the first half of the tale, with Watson (Andre Morell) handling the case. Inevitably the suggestions of a supernatural force at work turn out to be cover for a very human plot to seize the family inheritance and for various reasons (budgetary and technical) Fisher fumbles slightly when the two threads, naturalistic and horrific, come together at the climax. Still, this is one of the most satisfying Holmes adaptations, with Cushing and Morell working well together – and Morell in particular capturing the character of Watson as portrayed in the stories far more accurately than many of the Nigel Bruce-influenced bumblers who litter Holmesian cinema.

The studio provides all the resources usually devoted to their Gothic horrors, with dense production design, excellent photography by Jack Asher (along with Arthur Grant, the most important cameraman to work for Hammer), and a great cast which includes Christopher Lee in the supporting role of Henry Baskerville. It seems a pity that Hammer didn’t follow The Hound of the Baskervilles with a series of Holmes movies, although it appears that they were drawn here more to the horror element than to the detection and few of the other stories are open to that kind of treatment (“The Adventure of the Speckled Band”, “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot” and “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” perhaps).

It would be nice to see a few of the films in the Universal set given this kind of treatment in a region A edition.

Comments