Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922): Criterion Blu-ray review

If memory serves, the first time I saw Benjamin Christensen’s silent film about the European witch craze, which was at its fiercest from the 14th to 17th Centuries, it was on a rental VHS of its 1960s iteration, Witchcraft Through the Ages (1968), re-edited by Antony Balch, with narration spoken by William S. Burroughs. The sound of Burroughs’ distinctive voice was enough to give the impression that the film was inherently camp, its depiction of Satanic practices and the Church’s often perverse and always violent response a somewhat mocking critique of the absurdities of superstition and the ignorance of power – released at a time when power and authority were under attack from a generation which had no respect for those who tried to control their lives.

Christensen’s film was an ill fit for this purpose, Balch’s use of the material giving a distorted impression which pushed it towards a kind of Reefer Madness absurdity. When seen in its original form, as Christensen intended, Häxan (literally The Witch, 1922) is a more complicated piece of work, an essay on certain forms of madness apparently inherent in the human animal. After a deceptively dry opening lecture on pre-modern cosmology and the superstitions which evolved in most societies to explain things not understood as natural science, Christensen dramatizes a number of aspects of those superstitions which took such powerful hold in the Middle Ages – God and the Devil, a belief that pacts formed with the latter could affect the material world in malevolent ways, and the resultant idea that certain violent means were necessary to root out those who practised evil.

It’s one of Häxan’s strengths that Christensen (like Ken Russell five decades later in The Devils [1971]) was able to see events from the perspective of those who were immersed in the world view of that time. He doesn’t stand outside as a critic, but rather attempts to understand these people’s grotesque behaviour from within their own beliefs. While there are touches of humour in the film – the early scene in a witch’s kitchen where a complaint is made about the sorry state of a thief’s rotting hand salvaged from the gallows, or the amorous fantasies of a serving woman as she imagines the effects of a love potion on her grotesque master – the dense production design of Richard Louw and the superb photography of Johan Ankerstjerne give the whole film a remarkable air of tactile authenticity, adding to the impression that these staged recreations possess documentary credibility.

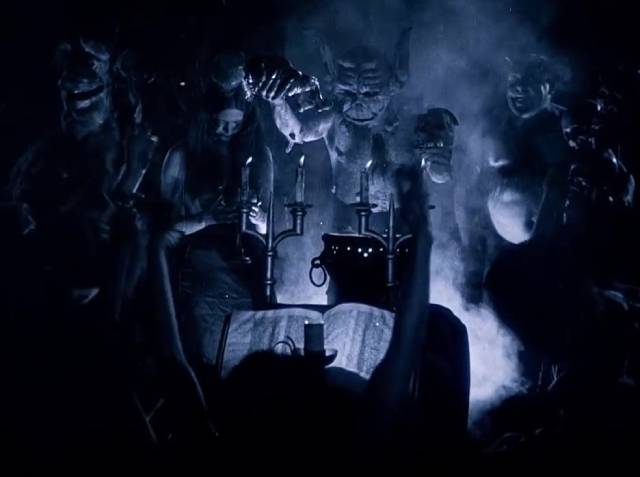

But Christensen complicates things further by erasing any lines between the objective and the subjective. He slips, without signalling any shift, between horrific events – the arrest and torture of the old peasant woman (Maren Pedersen) – and the participants’ nightmarish fantasies – the old woman’s narrative of her pact with the Devil, of giving birth to monstrous demonic children, her exhilarating flight to the witches’ Sabbath where she joins others in pledging allegiance to Satan. All of this is portrayed with the same attention to convincing detail as the more “objective” scenes.

Christensen doesn’t shy away from the psychosexual currents underlying the delusions of both witch and inquisitor (anyone who has read – or tried to read – the Malleus Maleficarum [1487] will recognize the sexual sickness which drives the inquisitors, and by extension the Church’s horror of women), and the main body of the film is almost stifling in this thick atmosphere of unwholesome pathology. The Sabbath is rife with perverse sexuality, while the inquisitors scourge their flesh to drive out unwanted thoughts of sex. But having laid out in such convincing detail this disease of the human mind and spirit, in the final section Christensen stumbles by trying to clarify it all with a modern diagnosis rooted in Charcot’s theories of hysteria.

This modern section focuses on a young woman suffering from a nervous condition brought on by the loss of her husband in the War. Her inner turmoil is expressed through kleptomania and its treatment requires doctors and science rather than inquisitors and religion. Although in the last images, Christensen does suggest that the certainties of science may be as delusional as those of the Medieval Church, this final chapter inadvertently puts the onus of the witch craze back onto the female victims, positing a mental condition which modern science comprehends but which the inquisitors misinterpreted with the unconscious complicity of those they tortured and killed.

Neither drama nor documentary, but rather a complex, multi-layered essay which explores a horrific subject with insight, Häxan is devoid of many of the “faults” we now perceive in silent cinema. The acting is for the most part quite naturalistic rather than overly theatrical and demonstrative – in particular, Pedersen, a non-actor, is magnificent as the old woman who comes to believe in her own guilt during interrogation. The film contains within it a catalogue of horrors which came to define the genre – demons, the personification of evil, the murder of children, cannibalism, torture, madness, sexual perversion – and it expresses these things without Expressionist exaggerations, giving it a surprisingly modern tone. The film’s influence is also apparent in the work of Carl Th. Dreyer, particularly in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), with its intense focus on faces to access psychological states, and – not surprisingly – in Dreyer’s own exploration of similar material in Day of Wrath (1943).

Stripped of Balch and Burroughs’ self-conscious textual manipulations, Häxan stands as one of the most remarkable films of the silent era, one which doesn’t require allowances on the part of the modern viewer.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray has been mastered from a new 2K restoration by the Swedish Film Institute, scanned from a 35mm internegative. The image is magnificent, rich in detail, with deep blacks and excellent contrast. This new edition has toned down the colour tinting seen on Criterion’s old DVD, with much more subtlety and finer detail. The musical accompaniment is a recreation of the original score compiled for the film’s initial screenings, undertaken by music specialist Gillian B. Anderson in 2001; the accompanying booklet contains a brief essay by Anderson about the difficulty of this task.

The supplements

The Blu-ray essentially duplicates the earlier DVD (almost twenty years old!). There’s a brief introduction from Christensen filmed for a 1941 reissue (8:11); the audio commentary by film scholar Casper Tybjerg; a collection of outtakes (4:33) which includes test shots for other films, but most interestingly shows Christensen trying out ways to film the flight of the witches to the Sabbath; a slideshow gallery (15:04) annotating Christensen’s sources for the illustrations used in the opening section; and, of course, Witchcraft Through the Ages, unrestored and by comparison revealing just how superb the restoration of Häxan is.

The booklet contains Anderson’s essay about the score from the DVD release, along with an updated version of Chris Fujiwara’s essay from the same release, with the addition of a new essay by academic Chloe Germaine Buckley about the film’s depiction of witches and its relationship to the actual history of the witch craze.

Comments