DVD diary: September – part two

Dark Of The Sun (Jack Cardiff, 1968)

The great cinematographer Jack Cardiff, responsible for the dazzling imagery of Michael Powell’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948), and Albert Lewin’s Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), among many others, was also a director. One of my earliest movie memories comes from Cardiff’s The Long Ships (1964), in which Richard Widmark plays a Viking who heads for North Africa in search of fabled treasure. Sidney Poitier’s Aly Mansuh has built a rather nasty execution device called the Mare of Steel, a giant blade shaped like a horse’s neck with a small platform at the top and a lot of sharp spikes at the bottom; the victim is flipped off the platform, slides down the blade, and the pieces end up on the spikes. That’s the kind of image that stays with you, particularly when you see it at age ten.

Cardiff’s adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers (1960) won numerous awards (including, ironically, an Oscar for Freddie Francis’ cinematography), but most of his films, like The Long Ships, were somewhat less prestigious. There was, for instance, the arty, fetishistic The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), with Marianne Faithful in leather crossing France for a reunion with her lover, Alain Delon, flashing back over their hot relationship as she rides the title bike. The movie is quite enjoyable until it ends abruptly with the girl being severely punished for her sexual freedom. Then there was The Mutations (1974), in which the always reliable Donald Pleasance experiments with human-plant hybrids in hopes of ending world hunger; you can probably predict the unfortunate consequences in this silly, but entertaining low budget horror also known as The Freakmaker.

And now the Warner Archive has just released one of Cardiff’s best features on DVD. Dark Of The Sun (1968) is what you could call a “muscular adventure” in that it’s chock full of armed men sweating in the African heat, fighting battles and killing each other over a fortune in diamonds. It’s also a pretty brutal and cynical action movie which wastes no time on the moral issues raised by having as its hero a mercenary hired by a dictator in the Congo and sent up-country to fetch a stash of diamonds for a Belgian mining company threatened by savage rebels. It’s all very well staged, mostly shot on location (the limited use of process shots is quite jarring at times, perhaps even more so because they’re used infrequently), with a strong cast headed by Rod Taylor and Yvette Mimieux (together again for the first time since The Time Machine [1960]}, and much of it takes place on a speeding train, which is always a plus. It would make a great double-bill with J. Lee Thompson’s colonial “western”, North West Frontier (1960).

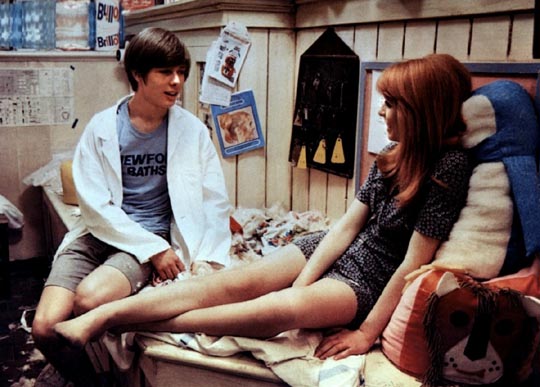

Deep End (Jerzy Skolimowski, 1970)

Although made only two years after Dark of the Sun, Jerzy Skolimowski‘s Deep End (1970) might as well come from another planet. I’m not sure why Polish directors faced with an English subject end up immersing themselves in sexual anxiety, but here Skolimowski follows the trail blazed by Polanski with Repulsion (1965) and Cul-de-sac (1966). School-leaver Mike (John Moulder-Brown) takes his first job at a public bath somewhere in London’s East End and quickly becomes infatuated with Susan (Jane Asher), a slightly older employee, who takes great pleasure in teasing him for his inexperience. She sets him up for embarrassing situations with older women customers who enjoy passing time with young boys (an apparently fearless, middle-aged Diana Dors has a terrifically funny and disturbing scene in which she uses Mike as a kind of masturbatory sex toy). Deep End is beautifully shot in vivid colours, with a terrific cast, and a steadily escalating atmosphere of discomfort which culminates in a darkly shocking climax. Given the richly evoked sense of a rather seedy area of London, it’s a surprise to learn that most of it was shot in Munich. The BFI’s edition features an excellent making-of documentary.

Wolfen (Michael Wadleigh, 1981)

I recently gave Michael Wadleigh’s Wolfen (1981) another try because of Jonathan Rosenbaum’s enthusiastic remarks in his DVD column in the summer issue of Cinema Scope (Vol. 13, #2). I recalled not being very impressed when I saw it on its original release, but hoped that there would be more to it than I remembered. Rosenbaum says: “Wolfen is a shotgun marriage of epic proportions, attempting to reconcile the suggestively ambiguous and arty moves and moods of Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942) and The Leopard Man (1943) – including similarly elliptical uses of parks, alleyways, zoos, and bedrooms – with the gargantuan allegorical conceits of M (1931) and Metropolis (1926), not to mention an echo or two of Riefenstahl’s Tiefland (1954), with its own mystical reverence for wolves. Even if, like so much of the best of ’60s grandiosity, it never fully achieves narrative coherence, it’s an exhilarating head trip.”

So I returned to Wolfen eager to discover what I might have missed back in 1981. There’s no question that Wadleigh’s use of locations – an area of New York which appears to have been flattened by aerial bombing, a small riverside park, an opulent, modernist uptown apartment – is quite remarkable, but Albert Finney is still hard to take as an American cop. Yet, for me, it’s the underlying story that never gels, the murder mystery that turns into a monster tale in which by the end we are asked to see the monsters as noble and human society as the villain (a thesis I certainly wouldn’t argue with; it just never really comes into focus dramatically). Whitley Strieber’s mystical mumbo-jumbo about a race of sentient wolves linked with Native American culture which lurk at the edges of human civilization, preying on the weak, doesn’t really amount to much in the end. By the finale, in which the wolfen have become a purely mystical force, apparently here to give us lessons about how not to be capitalist exploiters, the movie has run out of steam.

Bad Moon (Eric Red, 1996)

But for all its weaknesses, it’s still better than Eric Red’s remarkably inept werewolf tale Bad Moon (1996). With a poorly shot prologue supposedly taking place in an Amazonian rain forest, but actually shot on a cheesy studio jungle set, in which a nameless bare-breasted starlet is the first victim of the beast, your expectations are automatically set pretty low. But the dull story which unfolds in the Pacific northwest, where Michael Pare goes in hopes that the proximity of his sister (Mariel Hemingway) and her young son will help him combat the monster inside him, is perfunctory and incoherent. Pare almost immediately stops struggling against his curse and becomes a characterless killer prowling the woods, while it takes his sister an interminable amount of time to figure out what’s going on. It’s hard to believe that this comes from the guy who wrote Near Dark (1987), obviously the high point of his career.

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, 1957)

Although I know of his reputation as an animator and a maker of live action, satirical cartoons, I haven’t seen much of Frank Tashlin’s work. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957) has eye-catching visuals, but I can’t say I was very strongly engaged by its satire of television, advertising and celebrity culture. Tony Randall plays ad-man Rockwell P. Hunter who’s desperately trying to save his job; he hits on a plan to get a lipstick endorsement from Hollywood bombshell Rita Marlowe (Jayne Mansfield) and just happens to approach her as she’s having problems with her boyfriend (Mansfield’s real-life husband Mickey Hargitay). Hunter suddenly finds himself her new “boyfriend”, instantly famous as the best lover in the country. Needless to say this causes problems with his fiance. My main problem with the film is that it actually plays like the TV sit-com it’s supposedly ridiculing. It’s amusing, but not really funny, and the sometimes clever visuals aren’t enough to sustain it.

L’Illusionniste (Sylvain Chomet, 2010)

I’m a big fan of Sylvain Chomet’s The Triplets of Belleville (2002), a funny, visually inventive animated feature, so when I was in Paris last year I was excited to see posters everywhere for his new film, L’Illusionniste. In fact, it ended up being the only movie I went to see during my six weeks in the city. I loved it. Watching it again on Blu-ray, I have to admit that it doesn’t work as well on the small screen. It’s a very quiet, subtle film and much of its charm derives from the beautifully rendered storybook art work.

I know a number of animators who dislike Chomet’s work and I don’t really understand why. But there have been complaints about L’Illusioniste which have nothing to do with the animation. The movie is based on an unfilmed screenplay by Jacques Tati, one which he apparently wrote to work out issues arising from his abandonment of his eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne. In transforming the protagonist, an aging stage magician whose career is failing, into Tati himself (a remarkably faithful portrait of his stage and screen mannerisms), Chomet has invited a kind of criticism which arises not from the film itself but from the background story, Tati’s own life and failings. Seen from this perspective, L’Illusionniste is definitely problematic because it presents a character who goes out of his way to care for a lonely, abandoned girl, sacrificing more and more for her well-being until she eventually abandons him. Rather than an apologia for having abandoned his own child, this casts him as the sad victim.

But is it valid to criticize the film for this backstory? Chomet obviously made L’Illusionniste as an homage to Tati the filmmaker, never intending it to be a commentary on the man’s personal life. Tati was a great filmmaker, but perhaps not a very nice person … but if we start to discard art because of the personalities of the artists who create it, there might not be much left at the end of the day. As a narrative in its own right, L’Illusionniste is a sweet, melancholy meditation on the transience of relationships and the drifting sense of loss that goes with growing old.

La Zona (Rodrigo Pla, 2007)

In the past couple of decades, Mexican cinema has gained international prominence with the work, particularly, of Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuaron, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and Carlos Reygadas. Each of these directors has moved to some degree from national to international filmmaking, with the first three embarking on successful Hollywood careers. But there are other Mexican filmmakers we hear less of, working within their national industry.

A friend recently lent me a copy of the first feature by Rodrigo Pla, La Zona (2007), which turns out to be an excellent thriller with strong overtones of social criticism. The “zone” of the title is a large, protected community in Mexico City – not so much gated as fortified behind a massive wall, scanned by numerous closed circuit cameras monitored by a private security force. Within these walls, the community appears to be an idyllic suburban enclave populated by comfortable middle class families who have separated themselves from the chaotic society which surrounds them. They have been given their protected status on the condition that they remain peaceful and conflict-free.

During a storm one night a large billboard outside the wall collapses, creating a makeshift bridge over which three teenagers climb, intent on committing a bit a robbery. Things go wrong and one of the residents is killed and the alerted neighbours gun down two of the boys, leaving one of them trapped inside the fortress. To protect their status, the residents have to conceal what has happened, trying to keep the police out as they hunt for the third boy. Rifts open within the community as some are appalled at the violence, while others eagerly plan to kill the remaining boy to conceal these events. The film follows this boy and the son of one of the community leaders who finds him and tries to hide him from the mob. Things end badly with the vigilante community making a deal with a corrupt police commander which seals the boy’s fate.

La Zona is a very polished piece of work, skillfully directed and well-performed by a large cast.

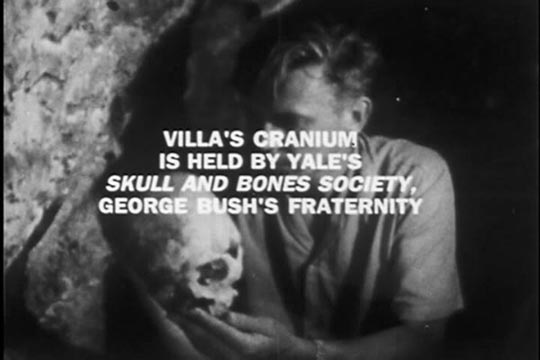

Mock Up on Mu (Craig Baldwin, 2009)

Mock Up on Mu (2009), the latest feature from cinematic scavenger Craig Baldwin, is something completely different. I was so strongly hooked by Baldwin’s first short feature, Tribulation 99 (1992), that I’ve eagerly sought out each new film (only three in the past twenty years). Starting in the mid-’70s, Baldwin began making “prank documentaries” out of bits and pieces of other people’s films, constructing collages which critiqued advertising, consumer capitalism, colonialism and various forms of political banditry and oppression. Following Tribulation 99, he made Sonic Outlaws (1995), an actual documentary starting from the legal case involving Negativland’s “appropriation” of U2’s music, tracing the forms of artistic resistance to corporate control of creativity – obviously something of vital importance to his own work. In 1999, Baldwin made Spectres of the Spectrum, an alternative history of the harnessing of Earth’s electromagnetic fields for communication, the corporate takeover of the planet’s natural energy. Here, he began to insert original elements, scenes with invented characters shot on threadbare sets designed to match the low-budget B-movie clips Baldwin uses to construct his films.

Baldwin’s latest, Mock Up On Mu, goes further down that road, relying more heavily on staged material. Paradoxically, the more he uses original, constructed material, the less clear his work is becoming. This paranoid fantasy linking L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology with U.S. rocket research, the military-industrial complex and New Age mysticism, never quite comes into focus, though it’s twice as long as Tribulation 99. The found footage montages seem more random here, and the overall effect is both less entertaining and less thought-provoking than in the earlier films.

Immediately after watching Mu, I popped Tribulation 99 into my player just to remind myself of what it was that I liked about Baldwin’s work and found myself riveted, watching the entire film again instead of just sampling it. This paranoid rant about aliens from inside the Earth causing political chaos in Latin America is both funny and strangely convincing as a metaphor for U.S. interventionism in the region. No doubt creating an entire movie out of nothing but fragments of other films – educational, industrial, cheap sci-fi and thrillers – is more difficult and time-consuming than shooting scripted (or even improvised) scenes with actors, but the end result is definitely more rewarding. (Note: I had the great pleasure of meeting Craig Baldwin just five months after writing this.)

*

Also viewed (and many of these warrant in-depth comment):

Stake Land (Jim Mickle, 2010), Requiem for a Village (David Gladwell, 1975), Season of the Witch (Dominic Sena, 2011), Insidious (James Wan, 2010), The Chess Player (Raymond Bernard, 1927), Cedar Rapids (Miguel Arteta, 2011), Paul (Greg Mottola, 2011), Super (James Gunn, 2010), Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (John Newland, 1973), The Boy Friend (Ken Russell, 1971), Colossus of New York (Eugene Lourie, 1958), Frost/Nixon (Ron Howard, 2008), The Flim-Flam Man (Irvin Kershner, 1967), Canyon Passage (Jacques Tourneur, 1946), Black Legion (Archie Mayo, (1937), Live Like a Cop Die Like a Man (Ruggero Deodato, 1976), Broadcast News (James L. Brooks, 1987), TrollHunter (Andre Ovredal, 2010), The Mafu Cage (Karen Arthur, 1978), Grand Slam (Giuliano Montaldo, 1967), Cold Fish (Sion Sono, 2010), Daguerreotypes (Agnes Varda, 1976), Wall Street (Oliver Stone, 1987), La Rabbia (Pier Paolo Pasolini & Giovanni Guareschi, 1963), 13 Assassins (Takashi Miike, 2010), Street Law (Enzo G. Castellari, 1974), Frantic (Roman Polanski, 1988), The Ark (Molly Dineen, 1993), Sands of the Kalahari (Cy Endfield, 1965).

Comments