John Huston’s Let There Be Light (1946)

I sometimes feel kind of oppressed by the Internet – too much stuff to look at and read, and not enough time. I know I miss a lot, but you can’t spend all your time surfing. So it’s always a pleasure when someone you do check in with occasionally points you towards something of real interest. Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant is always posting interesting links, and just this past weekend I happened to find a link over at the Self-Styled Siren to John Huston’s third and final War Department documentary, Let There Be Light, shot in 1945, completed in early 1946 … and then suppressed by the War Department until 1980.

I watched the film on the National Film Preservation Foundation website before reading the fascinating backstory (unfortunately, it’s no longer available for viewing there, but it was included as a supplement on the Blu-ray edition of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master). Initially, I felt a little ambivalent towards this record of a group of returning soldiers with “psychoneurotic” conditions – commonly called battle fatigue or shell-shock back then, now known as post-traumatic stress disorder – because Huston brought to bear all the resources and techniques of Hollywood narrative filmmaking. After the opening text telling us that everything was simply observed as it happened, we see what appear to be scenes constructed through editing, elaborate montages with music, and a series of apparently miraculous “breakthrough” moments in which the rather aggressive doctors crack the neurotic shells which trap the soldiers in various incapacitating states.

But all of this is part of the film’s didactic purpose – an attempt to assure a general audience that these war-damaged men are not “crazy”, but rather just like anyone else who’s been subjected to intolerable stresses, and deserving of sympathy and understanding. Given that purpose, what gradually becomes visible during the film is a series of startling, even radical “subtexts” … and it was no doubt these which pushed the War Department sponsors to suppress Let There Be Light.

First, of course, is the idea that shell-shocked soldiers are not fundamentally weak individuals who let down their comrades and the forces they were fighting for. The general military attitude of the time was clearly represented by the scene in Franklin Schaffner’s Patton (1970) in which the outraged general hits a young soldier he calls a “snivelling coward”, unfit to be in the same hospital ward as real men with real wounds. The idea that these “psychoneurotic” men were just ordinary people pushed too far by the circumstances of war undermined the image of the soldier as a strong, brave, noble figure capable of taking anything and still doing the job.

But even more startling than this idea is the film’s most radical aspect: in a time when the forces were still segregated and black soldiers more or less pushed out of sight, Let There Be Light mixes the races without comment or emphasis. In fact, the most verbally articulate, even sophisticated, man is a black soldier who speaks of his girlfriend as being the only person who ever gave him a sense of self-worth, and of his mother fiercely trying to instill in him some sense of his superiority to the poorer kids in his neighbourhood. At a group session, it’s a white soldier who says that what he wants most is for all these men to be given a chance and to be recognized as equal to anyone else.

While the somewhat miraculous presentation of psychological healing masks the sheer hard work that recovery actually involved, the communal presentation of this diverse group of soldiers and the insistence that they are indeed all equal, with the same aspirations and right to a fair chance, turns the film into a radical critique of the society which sent them to war, and by implication a call to transform the post-war world into something better. No wonder the generals balked.

Although the official explanation for the suppression was that Huston’s film violated the privacy of the men who took part, the real reasons become very clear when you see the remake released in January 1948. Called Shades of Gray (directed by silent actor and later prolific director of documentary and entertainment shorts Joseph Henabery – Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation), it “corrected” all the troubling aspects of Let There Be Light. Firstly, it eliminated any actual use of documentary (apart from some stock footage ironically pillaged from Huston’s The Battle of San Pietro [1945]), restaging combat and hospital scenes with actors (in a number of cases, recreating specific moments from Huston’s film) and smothering everything under a relentlessly self-assured “educational” voice-over which, in telling us exactly what’s going on at every moment, removes all ambiguity, not to mention nuance, and makes it unnecessary to hear what the characters are saying. This oppressive paternalism is embedded into every aspect of the film, which can be viewed in eight parts on the Internet Archive website, starting here.

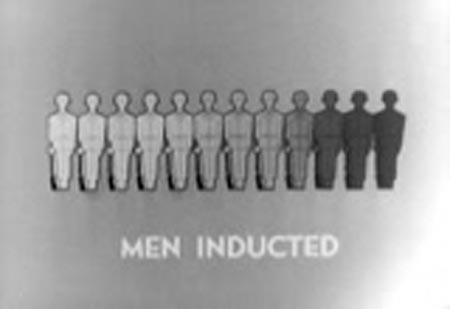

Reversing Huston’s point that war can shatter the nerves of anybody, Shades of Gray starts out with a lengthy dissertation on those who are inherently “sick” and who must be weeded out from the forces at induction. It turns out that the mental health of the nation comes down to two things: good mothering and bad mothering. Good mothers instill strength, determination and self-confidence in boys which make them fit to face life’s challenges, while bad mothers smother their sons with misguided over-protective love which makes them helpless in the face of ordinary life, let alone the stresses of war.

Inevitably, the film feminizes what it refers to as “neuropsychosis” and assures us that the weakest sissies get weeded out by the selection process. However, as the title emphasizes, we all exist along a spectrum of mental health, so even those who pass selection may eventually exhibit weakness at some point when subjected to the stress of military life. That’s where a smart, paternalistic command comes in, detecting such weakness before it causes trouble, and treating the “sick” quickly, sometimes by reassigning them to less stressful duties, but often managing to break the hold of those bad mothers, enabling the weak to become “real men”.

Shades of Gray reeks of condescension and the certainty that military life and war strengthen and ennoble men … and if that doesn’t happen it’s due to innate weakness. The flat awkwardness of the performances contrasts sharply with the authentic pain and confusion seen in the real soldiers in Huston’s film. Essentially, the doctors in Shades of Gray tell the men to buck up and they do.

But apart from this total reversal of what we see of the psychological condition of the men in Let There Be Light, the most telling difference between the two films is the complete whiteness of the remake. No sign of black or ethnic soldiers at all. This cleansing takes on a chilling dimension in conjunction with the film’s insistence that the nation from which soldiers are drawn must be strengthened, that “the weak must be eliminated”. No sympathy for the traumatized here – it’s your own fault (or rather, your mother’s) if you can’t take it, and you should be swept aside to make way for the real men who matter.

Comments

Great review!

We’re linking to your article for John Huston Friday at SeminalCinemaOutfit.com

Keep up the good work!

Thanks. I appreciate the plug!