British fringe cinema from the BFI

Recent releases from the BFI include a pair of movies from the mid-’70s which didn’t leave much of a mark at the time and two experimental features made in the last few years by a filmmaker with an idiosyncratic, artisanal approach to narrative cinema.

Slade in Flame (Richard Loncraine, 1975)

When I saw Richard Loncraine’s Flame in 1975, I don’t think I’d even heard of the band Slade, or heard any of their songs. And yet they were apparently one of the most successful bands in Britain in the early ’70s, though they hadn’t managed to crack the North American market (I saw it in London; not sure if it ever played in Winnipeg). So, watching the film, I might have thought they’d been conjured up by the filmmakers, another ersatz band invented for the movies. I didn’t think much of the film at the time and all I could recall decades later was a sequence in which the band goes to a pirate radio station in the Thames estuary for an interview and find themselves under fire in the studio. Fifty years later, I’m still unfamiliar with the band, but watching the movie again on Blu-ray, nicely restored by the BFI, I find it much more interesting.

Which is not to say that the basic elements of the story, concocted by writer Andrew Birkin, aren’t very familiar – this is a showbiz rise-and-fall narrative which hits a lot of fairly conventional beats – but Loncraine, working on his first feature, and cinematographer Peter Hannan give it a gritty realism reflecting the seedier side of Britain very much adjacent to the world seen in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970) and Mike Hodges’ Get Carter (1971). Made a decade after Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) firmly established the public image of The Beatles, what seems most surprising about Flame is that rather than playing cheekily to Slade’s fans, it leaves the band in ruins by the downbeat ending – something the band and their management eventually decided was a mistake.

Although the four band members originally got together in 1966 (the year my family emigrated to Canada, which no doubt explains why I hadn’t heard of them), they didn’t reach the charts until 1970, after which they had a long run of top 20 hits. A few years into this success, making a movie seemed like the logical next move. Initially, they were pitched a comedy, but some of the members wanted to do a more serious film which reflected their own experience. What eventually emerged was Flame – or Slade in Flame, as it’s often designated. The story follows a familiar arc as local lads from Wolverhampton form a band as an escape from the daily working class grind, are scouted by some corporate types who begin to shape them into something with commercial potential and promote them to popular success … which paradoxically draws them away from the original impulse which had brought them together. The money, booze and parties end up making them forget their roots and the friendships which fuelled their creativity.

We’ve seen all this before, both in movies and actual life (Birkin included a lot of incidents actually based on the experiences of Slade and other bands). Even The Beatles only lasted ten years before internal conflicts broke them apart at the height of their success. But despite the familiarity of the narrative, Flame works because of its acute observation of its milieu, the details which evoke a specific time and place, and the personalities of the characters involved. While none of the band members had any acting experience, they possess an authentic energy which gives the film a convincing documentary feel. In the early scenes, music is a means of getting away for brief moments from low-wage jobs, even if the gigs themselves are unfulfilling. Initially there are two rival bands competing in a limited market of pubs and local halls; one is a cover band fronted by an overly theatrical crooner named Jack Daniels (Alan Lake), first seen performing at a wedding where they end up fighting with the guests; the other is The Undertakers, whose act mixes music with horror imagery somewhat reminiscent of performers like Alice Cooper – they wear elaborate make-ups and their opening number at a club has the lead singer start inside a coffin.

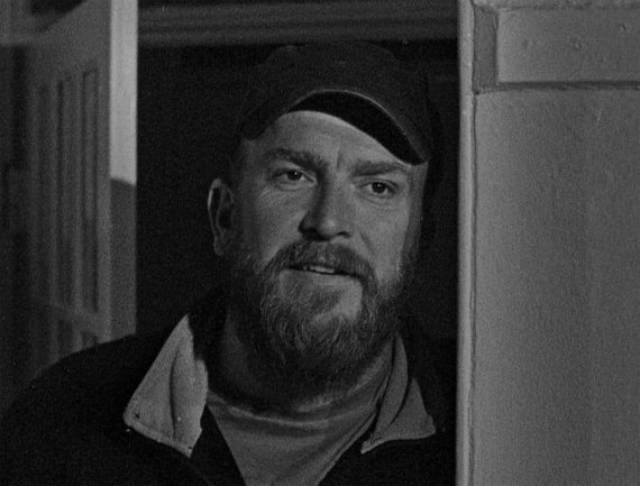

Initial rivalry eventually disappears as the bands re-form, members of both combining into what will become a glam rock quartet named Flame. Scouted at a local gig by Tony Devlin (Kenneth Colley, whose other significant musical connection is as the lead in Ray Davies’ Return to Waterloo [1984]), who works for a PR firm looking to branch out into the music business, they get a meeting with a slick corporate type named Robert Seymour (Tom Conti), who sees them purely as a product to be moulded into yet one more profit-making venture. The band members – Stoker (Noddy Holder), Barry (Dave Hill), Charlie (Don Powell) and Paul (Jim Lea) – go along with the image make-over despite misgivings, because a successful music career gets them out of the trap of low-income labour, but tensions inevitably arise because Seymour’s plans move them away from the authentic selves which led them to music in the first place.

There’s a slightly rushed quality to their rise as the film compresses the process into a few episodes – a contrived photo shoot, that visit to the pirate radio station, the sudden appearance of enthusiastic fans at an elaborate performance where the band are now dressed in flamboyant costumes reflecting the fire imagery implied by their name. Smaller moments reveal the cracks beginning to form in their friendships. Barry and his girlfriend Angie (Sara Clee) are less than happy to feel themselves being pulled away from their roots in the working class community, while Stoker embraces the celebrity lifestyle, at least for a while.

Considering Slade’s popularity at the time, the sordidness of the film’s portrait of the business and what it does to performers is surprising. Seymour, like everyone else at the firm, doesn’t even like the music and treats the band as nothing more than an exploitable commodity. As their market value increases, their old Wolverhampton manager resurfaces to claim his percentage. This is Ron Harding, a shady character with underworld connections played by Johnny Shannon, whose earlier appearance as Harry Flowers in Performance adds considerable menace to his role here. An undercurrent of violence runs through his “negotiations” with Seymour, the latter eventually coming to the conclusion that the band’s value has reached its limits – as the internal conflicts create irreconcilable rifts, Seymour decides it’s probably time to walk away. The rags-to-riches-back-to-rags arc has played out quickly, success proving temporary if not entirely illusory … and Slade’s fans, unable to separate the real band from the fictional Flame, were left with the impression that their favourite band was breaking up.

While the performance sequences are, not surprisingly, convincing – Slade obviously knew what they were doing on stage – the movie’s real strength is its slice-of-life depiction of the world the band emerged from and a big part of that rests on the personalities of the four band members. Unlike The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, who played somewhat mythical versions of themselves, you get the feeling that the four members of Flame are an authentic representation of the actual members of Slade.

The new transfer on the BFI disk looks excellent and supplements include a new commentary, a brief new interview with Conti, a long archival interview with Noddy Holder, a one-hour retrospective documentary from 2007 featuring interviews with Loncraine, Conti and the band members, plus a brief news clip from 1973 about glam fashions.

*

Eclipse (Simon Perry, 1977)

The British film industry was in a precarious position in the 1970s and producers tried various ways to keep production alive. The Eady Levy, which had been established originally in 1950, was essentially a tax on film exhibition which created a fund to be doled out to qualifying productions (something like Canada’s tax shelter of the 1970s and early ’80s); such subsidies led to outside investors putting money into projects shot in England – where for a time costs were lower than in the States, in particular – which is why films like Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and Ken Russell’s The Devils (all 1971) though produced in England were largely funded by U.S. studios. But others aimed for more modestly scaled projects rooted in more local narratives and themes, with small companies springing up briefly – like The Pemini Organisation, formed by three film school friends, who made three features in three years before moving on.

Similarly, two friends with a background in theatre and television created a production company called Celendine Productions in the mid-’70s intending to make features. Their first project suggested that commercial concerns weren’t foremost in their minds – Knots (1975) was a one-hour adaptation of a stage production based on a book of poetry by the influential psychologist R.D. Laing. Two years later, the company made its second (and last) feature. Eclipse (1977), based on a novel by Nicholas Wollaston, produced by David Munro and written and directed by Simon Perry, was a deliberately oblique drama which denied the audience the obvious satisfactions of the psychological thriller it superficially appeared to be – and after receiving little notice, it disappeared almost completely until its revival now as the latest release in the BFI’s Flipside series devoted to mostly obscure British cinematic oddities.

Eclipse seems determined to frustrate the viewer from the start, introducing us to the two main characters – Tom (Tom Conti) and Cleo (Gay Hamilton) – at an inquest into the death of Tom’s twin brother Geoffrey, to whom Cleo had been married. Tom’s testimony, recounting Geoffrey’s death in a boating accident, seems uncertain if not downright shifty and, although the coroner eventually rules it an accident, that uncertainty hangs over the rest of the film as it keeps circling back to the incident, not to provide new details but to reflect it through Tom’s unreliable memory. Are these different versions his way of trying to cope with trauma, or rather deflections to conceal guilt – does Tom even know himself whether what happened was an accident or a deliberate act on his part to rid himself of a brother who had dominated and belittled him his entire life? The film never resolves the issue, and this uncertainty overshadows the uneasy relationship between Tom, his brother’s widow Cleo, and his nephew Giles (Gavin Wallace).

While the unresolved question of what actually happened that night on the small sailboat suggests that Eclipse is a mystery, it actually plays as a character study about lives damaged by experiences reaching back far before the incident itself. Tom, born twenty minutes after Geoffrey, seems to be plagued by insecurity and self-doubt instilled by his brother’s aggressive self-assurance. Cleo is a high-functioning alcoholic whose condition may well precede Geoffrey’s death – an artist who has been unable to paint since the fatal incident, her work may not have been fully appreciated by her husband when he was still alive. The living room of the family home is dominated by a life-size portrait of a naked Geoffrey standing defiantly, perhaps aggressively, on the beach, the force of his personality still dominating the domestic space. At the same time, young Giles seems to have inherited his father’s aggressive certainty about his place in the world.

The story takes place over a few days around Christmas some time after the inquest; Tom arrives at night bearing gifts and a large turkey, and the broken family attempts to recreate holidays of the past which were obviously stage-managed by Geoffrey. Christmas dinner is a disaster because Tom doesn’t actually know how to cook a turkey properly – that was Geoffrey’s job. Having helped Giles set up the electric train set he’s been given, Tom is frustrated that the boy won’t play with it “properly”; he races the train around the room in reverse until it crashes, laughing gleefully. And Cleo just keeps drinking as she and Tom circle around the spectre of Geoffrey. Flashing back to the morning Tom returned alone and told her that Geoffrey was dead, his manner and expressions are confusing and contradictory, swinging from hysteria to a barely concealed glee – accident or not, Geoffrey’s death has somehow liberated him and trauma seems to be mixed with a kind of ecstatic relief.

Tom and Cleo eventually engage in sex, seemingly something which has been lurking in the background for a long time (and perhaps somewhat perversely a way for them both to engage with and exorcise the spectre of Geoffrey which hangs between them) and Tom takes Giles out sailing despite threatening weather. During this excursion, Tom slips back into his confused feelings about Geoffrey and rather menacingly seems to conflate Giles with his father – tension builds as the possibility that he is intent on repeating the “accident” in order to eliminate the last traces of Geoffrey grows stronger … but the moment passes and everything remains unresolved.

Eclipse is visually appealing thanks to Mike Berwick’s cinematography, which contrasts the claustrophobic family home with the landscape and sea around Caithness in Scotland, though the source (from the “best available 35mm archival materials”) is somewhat washed out, giving an overall chilly, muted impression. Although none of the characters are particularly likeable, Conti and Hamilton both give interesting performances, while Wallace as Giles is annoyingly precocious, though this suits his role as a miniature version of his arrogant father. The disk includes a commentary from Vic Pratt, a brief interview with Conti, three short PSAs warning of the danger of playing around water, and a pair of Scottish short films reflecting similar themes of family trauma and alienation.

*

Mark Jenkin

Watching Eclipse finally prompted me to tackle a couple of other BFI disks which have been sitting on the shelf for a while, both by Cornish experimental filmmaker Mark Jenkin. To be honest, I had been putting these off because I expected them to be a bit of a chore, a wariness which actually turned out to make watching them one of my most satisfying experiences in a while. Both Bait (2019) and Enys Men (2022) provide the kind of immersive, engrossing experience that I look for but too rarely find these days (and, yes, I’m aware that’s more than slightly due to the fact that I tend to look in the wrong places!).

The term “hand-made film” might loosely be applied to works by filmmakers working on the fringes with minimal resources – someone like Andy Milligan, for instance, who wrote, directed, photographed, edited and even made the costumes for his no-budget exploitation movies. But a more rigorous use of the term applies to filmmakers whose work is as much about the material nature of the medium itself, a hands-on manipulation of the celluloid – this generally includes experimental filmmakers like Stan Brakhage, Arthur Lipsett, Norman McLaren and the like who would go so far as to eschew a camera altogether and literally inscribe images onto the celluloid by hand. Often their work would be about light and movement in the abstract, disconnected from representation and narrative. It’s rare to find this concern with the materiality of celluloid allied with storytelling, and yet this is what we find in Mark Jenkin’s two features.

Jenkin uses a hand-wound, spring-driven 16mm Bolex to shoot his films, a choice which imposes certain rigorous constraints on his work. Limited to 100-foot loads (less than three minutes per reel), with a shot-length of less than thirty seconds per wind, it’s not possible to use elaborate camera moves or long takes; Jenkin must construct his sequences from short visual fragments, a technique which produces an intense focus on telling details – he uses tight close-ups not only of faces, but also of hands performing specific tasks, feet moving across different types of terrain, details of natural and constructed settings, infusing everything with a material presence and weight of significance which may not be immediately comprehensible, taking on meaning through the accumulation and juxtaposition of details.

In addition, because the speed of the film through the camera is imprecise – and because the motor produces considerable noise – it’s impossible to record sync sound, which means that everything – dialogue, effects, ambiences – has to be painstakingly constructed in post-production, the soundtrack itself becoming a form of hand-crafted art which works in tandem with the visual elements. And finally, rather than sending his exposed reels to a lab, Jenkin hand-processes the film in his darkroom. This, more than anything else, foregrounds the essential materiality of the medium, calling attention to the celluloid itself and not just the images recorded on it.

Bait (2019)

It’s this last factor which is most startling as you begin to watch Bait – as used as we are to pristine imagery, the plethora of scratches and constant fluctuations in image density is initially distracting, even disturbing, creating a kind of veil between the viewer and what is represented in the imagery. Hand-processing introduces an element of contingency, a voluntary relinquishing of control on the filmmaker’s part. While the film was actually shot just a few years ago, this gives it an impression of being a very old, much-handled print rising from the distant past. But once the viewer is accustomed to the look of the film, this quality assumes a thematic weight bearing on the narrative content which deals with conflicts between tradition and modernity, between a way of life closely allied to the natural world and a way of life separated from that world and defined by monetary values. The distressed visual quality of the film subtly draws the viewer into identification with a protagonist who lives in a constant state of anger at finding himself displaced and rendered all-but valueless in a world which is moving on without him.

This is Martin Ward (Edward Rowe), a fisherman in a small Cornish village who no longer has a boat and must spread his nets on a beach where he snags a meagre catch as the tide comes in. His brother Steven (Giles King) still runs their father’s boat, but only to offer tours of the coast to holidaymakers who have turned the village into something like a quaint theme park where people like Martin are relics providing local colour. The Ward house has been bought by Tim Leigh (Simon Shepherd) and his wife Sandra (Mary Woodvine), who have turned it into a bed-and-breakfast and have an on-going feud with Martin who constantly parks his truck in the street, inconveniencing their customers. The stress between Martin’s devalued identity as fisherman and the bourgeois gentrification of his family home gives the film an undercurrent of potential violence – a violence which eventually erupts from unexpected directions.

In addition to the conflict between Martin and Steven about the proper use of the boat, and between Martin and Tim over displacement from the family home, there are generational conflicts between locals and in-comers, fraught with jealousy and resentments and at one crucial point a disrespect which leads to a potentially transformative understanding when Tim and Sandra’s obnoxiously privileged son Hugo (Jowan Jacobs) damages Martin’s lobster trap and steals the lobster, which is then cooked and eaten by the Leighs. Feeling guilty, Sandra subsequently leaves money in Martin’s cottage, while Martin confronts Hugo in the local pub … his demeanour is threatening, but rather than attacking Hugo, he humiliates him in front of everyone by forcing him to repair the damaged trap, the boy for just a moment being exposed to the skilled manual labour of those he feels so superior to. Not enough unfortunately to cure him of being an arrogant dick.

While the film clearly seems on Martin’s side, he’s not an easy character to like unreservedly, and Jenkin also manages to find qualities in those he’s opposed to which evoke some sympathy – everyone here is flawed, all trapped in a messy web of traditions and change which are never quite as clear cut as the characters themselves might like to think. The film’s distinctive visual textures reflect these layers of experience and emotion, giving it an almost documentary-like quality despite its obvious stylization. As a mix of experimental technique and carefully observed social drama, Bait seems quite unique, the idiosyncratic work of an artist in full command of his art.

Enys Men (2022)

Although Jenkin hadn’t consciously intended the undercurrent of violence in Bait, seeing audiences respond to it he decided that his next project should be a horror film. Production was delayed by the Covid pandemic, and when he finally shot Enys Men (2022) it seemed tailored to the on-going situation; an introspective single-character narrative shot on a remote, deserted island off the Cornish coast, the film builds a cumulative sense of unease which gradually evolves into dread. Influenced by the tradition of folk horror, it’s set in 1973, which was the height of the genre’s first flowering – that was the year Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man was released, and also the year of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, to which Enys Men makes an apparently unintended visual reference.

Shot in colour, with a lush palette (and few signs of the distress produced by hand-processing), the film evokes a sense of obscure personal rituals which tie the character to the powerful forces permeating an ancient landscape. As in all British folk horror, the land is alive with energies which transcend time and assert influences over everything which occupies this space – plant, animal, mineral, and of course human. But while these forces are interpreted through a religious lens in The Wicker Man, here – as in Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape (1972) and Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England (2013) and In the Earth (2021) – they are ancient, preceding human awareness.

Jenkin creates a hypnotic effect through repetition as he depicts the daily routine of The Volunteer (Mary Woodvine again), who has come to this island for the very specific and limited task of observing a small cluster of plants growing on a precarious cliff edge. Dressed in a bright red rain slicker which sets her apart from this environment (and calls to mind the small red-clad figure which haunts John Baxter [Donald Sutherland] in Venice in Don’t Look Now), she crosses the island, inserts a thermometer into the soil to check the temperature, then returns to her cottage to make a note in her log book. Day after day, her comment is “no change”. Her walk takes her past a standing stone which overlooks the cottage and on her return journey she pauses at the open shaft of an old tin mine and drops a stone, waiting for the distant sound of it striking bottom. But the daily repetition of her routine is shown with subtle variations in framing and camera angles; nothing seems to change and yet each iteration is slightly different – time seems both static and fluid and gradually its depths are revealed in stratigraphic layers in which past, present and future exist simultaneously.

The Volunteer is surrounded by apparitions – miners deep in the shaft, women in folk costumes dancing on a hillside, a preacher (John Woodvine) sermonizing on the rocks, and a silent young woman (Flo Crowe) in the cottage whom we gradually realize is The Volunteer’s own younger self, a reckless girl given to climbing on the cottage roof despite warnings from her older self. There’s also The Boatman (Edward Rowe) who brings The Volunteer supplies – tea, fuel for a generator – and perhaps also eases her loneliness with laconic sexual encounters. But he also seems to be dead, drowned in the sea just off the island’s shore; The Volunteer manages to pry a board out of a cleft in the rocks on which is written part of the name of The Boatman’s launch.

Eventually something does change; The Volunteer discovers that lichen has begun to grow on the flowers she’s been observing. More unsettling, she discovers that lichen has begun to grow on the line of a long scar which runs across her belly and up her side, a scar whose origin we learn when the younger self falls from the roof and crashes through the glass ceiling of the yard housing the generator beside the cottage. The lichen spreads over both the flowers and the scar as if manifesting those layers of time, gradually absorbing The Volunteer into the accumulated history of the island landscape. As these layers of time fold into one another, the standing stone seems to be the pivot or anchor which holds everything together. Its position appears to shift, sometimes closer, sometimes more distant. And finally, The Volunteer herself becomes the stone, echoing the folk legends which say that stone circles are the petrified record of people who engaged in various rituals in the past.

Although Enys Men (the title is Cornish for “stone island”) was conceived as folk horror and it evokes many of the genre’s signature tropes, it doesn’t offer conventional scares, but rather produces a creeping sense of dread rooted in the idea that the land itself is ancient and alive and that its human occupants are transient and fragile and destined eventually to be absorbed back into the primal energy which transcends our limited sense of time. As in Bait, Jenkin produces a tactile quality which anchors the narrative in a visceral sense of place while minutely observing the behavioural details which arise from characters inhabiting that very particular place with its own deep history, all of which is given a material immediacy through his chosen hand-made technique.

*

The BFI dual-format editions of the two features both include extensive extras, including commentaries and Q&As. The Bait disk features three of Jenkin’s experimental shorts as well as a 1938 docu-drama about Cornish fishermen and a 1912 travelogue emphasizing the distinct qualities of Cornwall. The Enys Men disk has a feature-length discussion/demonstration of the uses of sound in films with Jenkin and Peter Strickland, plus a brief clip showing Jenkin at work on the soundtrack, and ninety minutes of audio diary entries recorded by Jenkin during production. There’s also a one-hour Children’s Film Foundation movie by Andrew Bogle called Haunters of the Deep (1984) which shares some locations and themes with Jenkin’s work, and another 1938 Cornwall travelogue. Each release comes with a booklet which includes a director’s statement and critical essays.

Comments