The rise of boutique DVDs: The Flipside

Even with the tens of thousands of movies released on DVD since the format debuted in the late ’90s, vast amounts of film history remain untouched. Of course, home video has always been a commercial enterprise, the preservation and dissemination of history mostly a by-product. Companies with large back-catalogues of titles have been constantly faced with the question of what to do with minor, more obscure movies which in themselves would have only limited commercial appeal. For years, companies like Warner Brothers, Sony-Columbia and Fox made dents in the backlog by issuing themed box sets – noirs, westerns, horror … collections of movies with limited commercial value by themselves, but which took on appeal to collectors because of the context supplied by multiple related titles.

An alternative approach would be what Criterion has done since the days of laserdisk, building up a prestigious image which adds cachet to any release bearing the company’s name. Their reputation, and the fiercely loyal customer base they’ve developed over the years has allowed them to take chances on what would otherwise be risky investments. But the downside of that strategy has been an occasional backlash against their programming choices. The release of Michael Bay’s The Rock and Armageddon in lavish two-disk sets was greeted with outrage from some who felt that it demeaned the label, and by extension their own taste. Similarly, there were objections when the company released a number of Richard Gordon’s genre productions (Fiend Without a Face and the Monsters and Madmen box set) and the very obscure amateur fantasy Equinox. Personally, I’ve always appreciated these choices because they indicate that the people at Criterion aren’t cinema elitists, but are rather driven by their own passion for movies in all forms.

Criterion, faced with the overwhelming amount of as-yet unreleased material floating around out there, started their Eclipse sideline a few years ago to take up some of the slack – themed sets focused on a particular director or genre, which allowed them to release far more titles than their main boutique line could ever accommodate (139 movies in 39 sets so far). But at the same time, mainstream companies were cutting back. Warners, formerly a leader in packaging American film history, phased out their richly appointed box sets, replacing them with their Warner Archive burn-on-demand line. While this allowed them to issue far more movies from their back catalogue than ever before, it also paradoxically limited access, at least to people like me who simply can’t afford to spend thirty bucks on a minor ’30s title where before I’d been happy to spend forty for a five-disk set with valuable extras.

MGM and Sony have followed Warners’ lead with burn-on-demand lines of their own, while other companies, like Paramount and Columbia, have begun to license their titles to new boutique companies like Olive Films, Legend Films, Twilight Time … companies issuing limited edition pressings for a fairly reasonable price. So while there are regular predictions of the demise of disks in favour of a new streaming-video culture, the marketplace continues to shift and adapt in recognition of a deep-rooted collector mentality that has become seriously attached to possessing movies as objects. In fact, for the collector, the new fashion in boutique publishers has revived a sense of excitement which had somewhat faded as the mainstream companies pulled back from taking chances the way they did in the wild early days of DVD. So we have Olive Films releasing items like Don Siegel’s Private Hell 36, Orson Welles’ Macbeth, Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (all on Blue-ray, yet) as well as fascinating, and until now virtually impossible to see, movies like Joseph Losey’s unflinching dissection of smalltown racism The Lawless.

While I’ve been a devoted buyer of disks from the BFI ever since I bought my first multi-region player, accumulating a large collection of their remarkable British documentary output in addition to a wide range of dramas, I’ve become particularly fond of their own boutique sideline, Flipside, since it was launched in May 2009 with Richard Lester’s The Bed-Sitting Room (1969) and a pair of mid-’60s “mondo documentaries”, London In the Raw (1964) and Primitive London (1965). That debut was a good indication of where the company intended to go with their avowed mission of “rescuing weird and wonderful British films from obscurity and presenting them in new high-quality editions”. In the ensuing three years, with a total so far of twenty-four releases (twenty-five if you include Flipside: Kim Newman’s Guide to the Flipside of British Cinema, a brief survey of the series and its intentions), Flipside has remained surprising and unpredictable. Ranging from the extremes of artiness in Don Levy’s Herostratus (1967) to the naturalism of Barney Platts-Mills‘ Bronco Bullfrog (1969) and Private Road (1971); from Peter Watkins’ futuristic critique of politics and pop culture Privilege (1967) to Guy Hamilton’s bleak attack on ’60s hedonism The Party’s Over (1963, released with no director credit after a heated dispute between Hamilton and his producers). In an alternate strategy to Criterion’s no-frills bundling, Flipside editions are generally fleshed out with rich and informative supplementary materials.

At times, the choice of titles has been puzzling. Why is David Gladwell’s meditation on rural life Requiem For a Village (1975) a Flipside release, while Tony Scott’s remarkable but un-commercial Loving Memory (1971) gets a mainline BFI release? And as the series has developed there’s been a definite tendency towards exploitation titles, when there are so many other areas which remain to be explored (horror, science fiction, comedy, crime).

That said, the series has uncovered a surprisingly wide variety of exploitation, both in terms of subject matter and treatment. Gerry O’Hara‘s work is finely crafted, even elegant, in All the Right Noises (1969), That Kind of Girl (1963) and The Pleasure Girls (1965), films which apply the English kitchen sink style to stories of the consequences of ’60s sexual freedom. Like most exploitation movies, there’s a tendency towards conservative moral attitudes, but O’Hara’s films wear them lightly, providing interesting and illuminating social documents. Pete Walker’s Man of Violence and Lindsay Shonteff’s Permissive (both 1970) aim lower, the former providing a crude action thriller laced with sex (most surprisingly in a sequence in which the tough guy hero has a casual homosexual encounter while looking for information), the latter revealing the bleak underside of the music business in the story of a naive provincial girl corrupted as a prog-rock groupie.

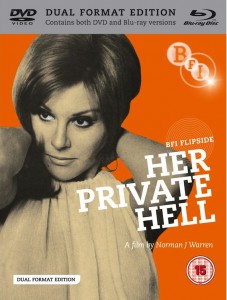

With their release of Norman J. Warren‘s Her Private Hell (1967), it seemed that Flipside had pretty much scraped the bottom of the barrel. Presented as the first indigenous British sex film, apart from a couple of interesting sequences in which Warren gets playfully experimental with his camera, it’s a dour, underdeveloped effort about a young woman from Europe lured to England with the promise of a modelling job, only to find herself essentially the prisoner of pornographers … but there’s little attempt at dramatic plausibility (what exactly the scheme of the villains is is never really clear) and certainly the sex angle is so restrained that even when the film was released it offered far less than what was already freely available in European productions.

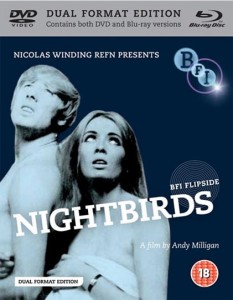

So when, on the heels of that release, Flipside announced that its next title was Andy Milligan’s Nightbirds (1970), it seemed that after a brief run the line had somehow exhausted itself. Milligan has a dire reputation as one of the most incompetent filmmakers ever to get a public showing, so it seemed that the people behind Flipside had made a decision to go for wretched rather than obscure-but-interesting. Nonetheless, being addicted, I found myself reluctantly ordering a copy from Amazon UK …

To be continued …

Comments

Could you help me get a copy of Privilege? DVD format? Or whatever?

Hey!

Hope my comment reaches you!

I am curious about the term “Boutique film”, which popped up heavily in collector`s circles over the last few years. But no one seems to have any strong definition or even a clue, where the term comes from.

I am looking into the matter to write a small paper for my studies and I was wondering if you have any idea where the term comes from or some advices on further readings (academic ones as well!).

Thanks a lot!

Magnus

I’m not familiar with “boutique film”, which as a term doesn’t seem to make sense. The use of “boutique” here refers to small niche companies which release a limited number of disks, usually with a particular focus on a type of film – genre releases are the most common. With the decline in major label releases as more big distributors turn to streaming rather than physical media, what were once boutique labels have in many cases expanded in recent years; companies like Criterion, Severin, Arrow, Vinegar Syndrome and Indicator have pretty crowded release schedules these days, while smaller companies like MVD and Cauldron are still working on the fringes.