More Italo-horror: The Good, the Bad and the Gory

With all the options open to me, given the current scale of my collection, I can’t seem to keep myself from revisiting Italian horror movies. I’m a sucker for upgrades and keep buying new editions … in search of what? Just an excuse to re-watch once more? Thanks to 88 Films and Cauldron, I’ve just indulged in four movies of wildly varying quality, one from the ’60s and three from the ’80s (with a footnote from the ’70s, courtesy of Severin).

88 Films

Lately I’ve found myself being drawn back into that rabbit hole thanks to 88 Films’ seemingly expanding production of nicely packaged restorations, which make them yet one more of the companies I monitor quite closely. Two of my recent acquisitions are movies from one of the hackiest directors of the golden age of Italian genre cinema, while the third is one of the most interesting movies by an undisputed master.

Bruno Mattei

Bruno Mattei’s work is crude and derivative, frequently cheaper rushed cash-ins on current box office successes, so seeing that 88 Films have lavished a 4K restoration and dual-format release on Hell of the Living Dead aka Virus aka Zombie Creeping Flesh (1980), I couldn’t resist. Mattei, collaborating as he frequently did with co-writer and co-director Claudio Fragasso, jumped on the zombie bandwagon set in motion by George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) and given a big Italian domestic push by Lucio Fulci with Zombie 2 aka Zombi (1979). For good measure, he also threw in elements from the then-current cannibal craze … and then fumbled the execution.

Around the world some shady corporation has established huge industrial plants called “Hope Centres” where they’re apparently developing the means to reduce over-population. As the movie opens, an accident in one such plant in New Guinea contaminates the workers, turning them into rotting, pustulent zombies determined to chomp on the living and pass along the contagion.

Elsewhere, a group of terrorists are holed up with hostages in an embassy, demanding that the Hope Centres be closed down. A tactical team infiltrates the embassy, killing all the terrorists – who make no attempt to kill their hostages for some reason. The four-man team are then dispatched to New Guinea on an ill-defined mission, where they run into a female reporter and her cameraman, who are on the trail of the story. The military guys are annoyed that they’re stuck with the civilians after their first run-in with the zombies, and there’s a lot of bickering as they head deeper into the jungle. However, given the reporter’s knowledge of the local tribes, they have to rely on her to get information from the natives.

When they reach the village, she strips naked and decorates her body with paint to fit in. Here, Mattei uses a bunch of variable-quality stock footage from documentaries (and Barbet Schroeder’s La vallee [1982]) for a bit of local colour. It turns out the village is already contaminated and the group barely escape to continue their journey, eventually reaching a river and heading downstream to the Hope Centre plant where pretty much everyone ends up dead.

While the threadbare narrative is fairly standard, Mattei’s staging of the action is so inept that it becomes almost hypnotic. If you’re frustrated by Fulci’s tendency to have his characters stand immobile as slow-moving zombies bear down on them, Mattei goes one better by having his characters clumsily deliver themselves into the hands and jaws of the infected. Walk backwards into dim rooms? Check. Put down your weapon and amuse yourself by trying on silly clothes from a closet? No problem. Stand with your back against an elevator door while you wait for it to arrive? We’ve got that. Rush into a crowd of zombies and taunt them? Oh yeah. Figure out that you have to shoot them in the head to stop them, but then keep emptying your clip into their chest? Sure, we’ll do that over and over again. The consistency of the characters’ stupidity is so relentless that you have to wonder whether Mattei has ever actually met a human being, or for that matter seen a movie. And it doesn’t help that he reuses a bunch of familiar Goblin tracks, particularly a lot of their score for Dawn of the Dead, which just reminds you of how far Mattei’s work falls short.

A movie like Hell of the Living Dead demands that you either abandon your critical faculties altogether or, like me, just keep yelling at the screen in frustration and disbelief. But given that, the 4K restoration looks surprisingly good and 88 Films have added a bunch of supplements including a commentary and several interviews, plus an amusing half-hour with Marc Morris (producer of Jake West’s Video Nasties documentaries) and critic David Flint reminiscing about the early days of home video and the video nasty backlash against movies like Zombie Creeping Flesh during the Thatcher years.

I don’t think I saw Hell of the Living Dead when it was first released – at least I can’t find it in my notes – but I did see Mattei’s Rats: Night of Terror (1984) on the big screen in late summer 1984. It was in either Munich or Berlin, under the title The Riffs III: Die Ratten von Manhattan, sold in Germany as a sequel to Enzo G. Castellari’s 1990: Bronx Warriors (1982) and Escape from the Bronx (1983), a pair of Italian post-apocalyptic action movies made in the wake of Mad Max (1979) and The Road Warrior (1981). I assume I saw it with a German dub, but it wouldn’t matter as dialogue is the least important element; the very basic narrative would be easy to follow in any language.

Hundreds of years after a devastating nuclear war, the Earth’s surface has long been abandoned as people moved underground. But now roaming bands scavenge the wasteland. A gang on motorcycles arrive in a ruined city and settle into a building with an old saloon-style bar on the ground floor and a dormitory upstairs where they find crates of food and a dead body in one of the beds, stripped of most of its flesh. There are rats everywhere and as the night goes on anyone who wanders off ends up overwhelmed by rodents – a drunken man falls into a sewer, a woman in a sleeping bag ends up eaten from the inside out. Soon the gang are fighting for their lives against a rapidly expanding tide of rats, the few survivors making it to dawn as figures in biohazard suits emerge from underground, subduing the swarm with gas. What I remembered most from the movie was the final “surprise” revelation that these men are actually large mutant rats walking upright.

Made on a small scale – it all takes place on one backlot street and in a single decaying building (apparently a set left over from Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America [1984]) – the plot consists of bickering among the gang about who’s in charge and an escalating series of rat attacks … well, maybe “attack” is an exaggeration. For the most part the rats just mill around, paying no attention to the actors until someone off-screen starts throwing them. As in so many Italian movies, there’s a certain amount of disturbing animal violence which is far worse than the fictional violence inflicted on the characters.

Nonetheless, Rats manages to function on a basic level more successfully than Hell of the Living Dead, making it one Mattei’s better movies. This is an older release without the deluxe treatment afforded Hell of the Living Dead, though the transfer is probably as good as the drab cinematography is ever likely to look. The only extras are interviews with a couple of cast members and composer Luigi Ceccarelli.

*

Mario Bava

Strangely, the third 88 Films release in this batch, although scanned in 4K and given deluxe packaging, doesn’t include a 4K UHD disk. Nonetheless, this is the best Mario Bava’s The Whip and the Body (1963) has ever looked on home video. Made just before Blood and Black Lace (1964), it’s as vivid as that film in its use of extremely stylized colour, but the challenge it has always posed for video is its darkness. Most of the movie takes place either at twilight or in large candle-lit rooms and cellars. Kino’s 2013 Blu-ray was problematic, with a murky image in which detail was lost in the shadows. This new transfer, while there’s considerable grain, fills in much of that detail, giving the film a rich, textured look which greatly enhances its atmosphere.

One of Bava’s best movies, The Whip and the Body is also his most perverse, a moody Gothic horror which revolves around an explicit sadomasochistic relationship. Perhaps more than any other early ’60s Italian horror movie, it echoes Roger Corman’s Poe cycle; the opening shots of a lone rider galloping along the shore towards a castle looming on a cliff above the sea seem like a direct reference to The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), while the imprecise period trappings situate the story in a psychological rather than historical context.

The rider is Kurt Menliff (Christopher Lee), disgraced son of a noble family returning from the exile he vanished into after provoking a servant girl, the daughter of the family’s housekeeper Georgia (Harriet White Medin), to commit suicide. Entering the castle, he oozes contempt and a sense of superiority as he “congratulates” his younger brother Christian (Tony Kendall) on his marriage to Kurt’s former fiancee Nevenka (Daliah Lavi). It’s not long before he resumes his relationship with Nevenka – finding her alone on the beach, he whips her, the violence inflaming her lingering passion. Despite her sense of shame, Nevenka simply can’t resist him, the intensity of her feelings highlighting the bloodless nature of her relationship with Christian.

Then one night Kurt is killed with the bloody knife with which Georgia’s daughter had committed suicide. Despite being interred in the family vault, Kurt seems unable to rest, returning to torment Nevenka with that whip, and eventually killing his father Count Vladimir (Gustavo De Nardo). Christian tries to get to the bottom of the apparent haunting, finally discovering the truth that Nevenka has gone mad, that she has internalized her tormenter and is simultaneously keeping their perverse passion alive while trying to eradicate her sense of guilt.

The overt sadomasochism drew censorship problems when it was released which somewhat sidelined the film until it began to appear in various DVD editions starting in 2000, peaking with the problematic Kino Blu-ray in 2013 until this new restoration. The disk includes two commentaries (but doesn’t carry over the Kino track from Tim Lucas), plus interviews with Bava’s son Lamberto, filmmaker Sergio Martino (whose brother Luciano was a co-writer and uncredited producer), and co-writer Ernesto Gastaldi. There’s also a booklet with three essays on the film.

Bava Footnote: I’ve also finally just got to see Mario Bava’s final film, a one-hour episode of a six-part television anthology called The Devil’s Game (1981). The ’70s had not been good to Bava. After initial success with Bay of Blood (1971) and Baron Blood (1972), his most personal project to date (and one of his masterpieces) Lisa and the Devil (1973) failed to secure distribution and was eventually butchered into a ridiculous Exorcist rip-off called The House of Exorcism (1975). Meanwhile, his attempt to move in a new direction, the poliziottescho Rabid Dogs, shot in 1974, remained unfinished because the producer ran out of money – it would eventually resurface in the 1990s, long after Bava’s death. Although he made something of a recovery with his final theatrical feature, Shock (1977), that project was partly devised to help Lamberto transition from his long-time role as Bava’s assistant director (since 1966), just as Riccardo Freda had helped Mario transition from cinematographer to director in the late ’50s.

On La Venere d’Ille (1979), adapted from Prosper Mérimée’s 1837 story, Mario shared the director credit with Lamberto, who had co-written the script. The film returns Bava to his Gothic roots, not simply because of the period setting and a troubled aristocratic family, but also in the doubling of the female character as both a contemporary woman and a menacing supernatural force from the past, similar to Barbara Steele’s dual-role in Black Sunday (1960), Bava’s first official film as director.

The film opens with a couple of workers uncovering a bronze statue of Venus as they try to dig up a troublesome tree root. As Signor De Peyrehorade (Mario Maranzana) supervises the raising of the statue, it slips and crushes one of the workers’ legs, immediately giving it a malevolent cast. A young scholar named Matthieu (Marc Porel) arrives to study the Signor’s collection of antiquities just before the man’s son Alfonso is due to marry the wealthy Clara (Daria Nicolodi). Matthieu is drawn to Clara and can’t understand why she’s marrying a boorish oaf like Alfonso; he’s also drawn to the statue of Venus, which he struggles to sketch, his drawing taking on the look of Clara.

On the morning of his wedding, Alfonso is diverted by a game of tennis, taking off his jacket and absentmindedly removing the ring intended for Clara from his own finger and placing it on the statue’s finger while he plays. Called away by his impatient father, he forgets the ring. That night, as Clara waits in the bedroom for the drunken Alfonso to arrive, Venus enters the room and takes her place in the bed. As she cowers on the floor, Alfonso stumbles in, goes to the bed and is crushed to death by his supernatural bride, leaving the family devastated and Clara insane.

Although made for television on a small budget, and seeming like a bit of a throwback – Gothic stories had largely been replaced by other genres by the mid-’60s – La Venere d’Ille is an atmospheric little film, nicely shot, with an excellent cast; Daria Nicolodi had two of her best roles in Bava’s final two projects, this and Shock. Although it’s impossible to know how Mario and Lamberto divided up the work, the end result is seamless and seems much closer to Mario’s movies than those Lamberto subsequently made.

Severin’s transfer was made from a 16mm print which shows a certain amount of damage, but is quite watchable. It’s the only episode of The Devil’s Game in the two-disk set with extras: a typically informative Tim Lucas commentary, plus interviews with Lamberto Bava and cinematographer Nino Celeste.

*

Lucio Fulci

For their first 4K release, Cauldron have chosen Lucio Fulci’s City of the Living Dead (1980), the director’s first horror movie after the international success of Zombie 2 (1979), and first of a loose trilogy which also includes The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery (both 1981). This trio aren’t really zombie movies, but more like Lovecraftian horror. To emphasize that point, City is set in the New England town of Dunwich (though shot further south in Georgia, along with some location work in New York and additional studio work in Rome). From the opening moments, Fulci establishes a mood of supernatural dread akin to Lovecraft’s cosmic horror as his camera prowls through a run-down cemetery, tracking a priest (Fabrizio Jovine) with haunted, bloodshot eyes as he throws a rope over a tree branch and hangs himself. We never know what drove him to this, but his sacrilegious act unleashes all the horror to come.

That horror is introduced at a seance in New York where Mary Woodhouse (Catriona MacColl in the first of her three roles for Fulci) has a vision of the suicide, suffers a seizure and dies. Investigating the event, reporter Peter Bell (Christopher George) observes Mary’s funeral and sees a pair of union gravediggers leave the grave open as their shift ends. He’s about to walk away when he hears a scream from the coffin and, rather irresponsibly, smashes the lid with a pick-axe which almost splits Mary’s skull. Trying to figure out what weirdness is afoot, Peter and Mary head out of the city in search of Dunwich, a town which doesn’t appear on any map. What they find is a desolate place, strangely depopulated, where a series of inexplicable events point towards an apocalyptic conclusion.

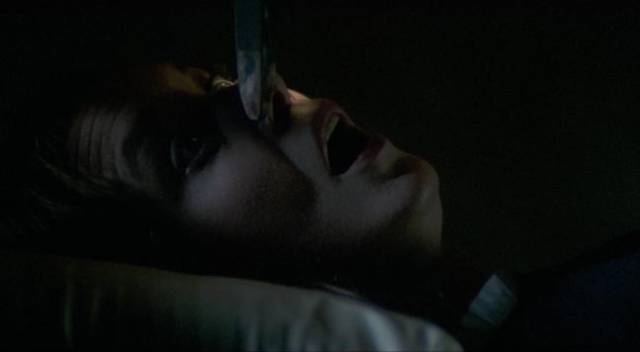

It seems that the priest’s suicide has opened one of the gates to Hell and the dead, rather than resting, are popping up to prey on the living. Their favourite technique is to grab the back of someone’s head and squeeze until the skull shatters and brains ooze out between their fingers. Not exactly zombies, not quite ghosts, they appear and disappear abruptly. The priest himself can kill with a look, most famously when he appears beside a car where a young couple are making out and, pinning the woman with his piercing gaze, causes her to vomit up her own stomach and organs.

The atmosphere of evil permeates the whole town, triggering acts of very human violence like the death of awkward loner Bob (the great Giovanni Lombardo Radice, who died just a few days ago) who is despatched by an angry father in a workshop where his head is pushed into a large drill press. Teaming up with local Gerry (Carlo De Mejo), Peter and Mary eventually find themselves deep beneath the town cemetery, where they make their final stand against the priest and his revenant minions, leading to an ambiguous conclusion.

I first saw City of the Living Dead in Hong Kong in 1980 (tucked between Francesco Rosi’s Illustrious Corpses and Abel Gance’s Napoleon) and, although certain images really stuck in my memory, in my notes it gets zero stars (the same rating I gave Zombie the following year). Perhaps it wasn’t the best place to start with Fulci and, as with most of his films, my appreciation has increased in the ensuing four decades. His tendency to push beyond “acceptable” limits and go full speed into the unapologetically gross has its own kind of integrity and I do like the way he conjures an atmosphere of doom – as he does similarly in The Beyond and The House by the Cemetery.

Cauldron have gone all-out with their first 4K release. The set includes a 4K disk plus two Blu-rays with the movie itself and four commentary tracks (two new, two archival) on disk one and four-and-a-half hours of mostly archival interviews and featurettes on disk two along with a standard definition copy of the VHS version of the film under the title The Gates of Hell. The limited edition also includes a separately packaged CD of Fabio Frizzi’s score, a sheet of stickers depicting all the gore highlights and a double-sided poster.

Comments