Martin (1976): George A. Romero’s masterpiece

Regional filmmakers, working with limited resources far from industry centres, often choose material which relies on familiar genre elements to boost their chances of some kind of commercial success. In broad terms, this was true of George A. Romero, who in the 1960s was a partner in The Latent Image, a production company in Pittsburgh which did a flourishing business in television commercials and commissioned industrial films. When he and his partners decided to try their hand at feature filmmaking, they decided to make a horror movie, shooting on evenings and weekends for the most part, working around their day jobs. But while the approach might have been calculated, it wasn’t cynical. Even at the start, Romero had larger ambitions and this shows not only in the thematic depth of Night of the Living Dead (1968), but also in the quality of the filmmaking itself. An accomplished cameraman and editor, Romero used all his skills to create a movie which was far more than an excuse for moments of shock and gore – although initial critical response generally couldn’t see past those elements to the underlying statement about American society collapsing under the stresses of social conflict and the Vietnam War.

At that time, horror was generally disdained as a genre, thought to be fit only for kiddie matinees and late night TV where it was framed with comic mockery from a variety of kitschy horror hosts. Although that same year the genre was given mainstream credibility by Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby, Romero’s movie was condemned in part because of its outsider origins – the industry and critical establishment formed something of a closed shop, unwilling to give credence to such an upstart.

Despite the creative accomplishment of NotLD, and its eventual commercial success and revised critical opinion, Romero and his collaborators saw virtually no return because, as outsiders, they were at the mercy of dishonest distributors whose skill at keeping all the profits for themselves is an all too familiar story. So, having made a film which would soon be seen as radically redefining the genre into something more adult as well as pointing the way towards a viable model for independent regional production, Romero and his partners returned to the more secure business of commercials and industrial films for the next three years.

When they tried again, it was with something very different. They weren’t driven by a particular desire to make horror movies – that initial choice had undeniably involved a commercial calculation – so much as a desire just to make movies. And so the eventual follow-up was a contemporary drama with comic undertones about a generation’s malaise in light of the collapse of social and political certainties at the end of the ’60s. But making There’s Always Vanilla aka The Affair (1971) was the antithesis of the experience of the first feature; conflicts within the group left everyone dissatisfied. And yet Romero achieved some momentum, making two more features in relatively quick succession, each drawing him back towards the horror genre, but affording him an opportunity to approach it from different angles.

Season of the Witch aka Jack’s Wife (1972) draws on Ingmar Bergman’s explorations of middle class people confronted with a crisis of belief, but situates it in suburban America at a time when a new wave of feminism was breaking down conservative attitudes about marriage and family. But here, consciousness-raising comes in the form not of political awakening but rather in the embrace of pagan spiritual beliefs. Once again running into problems with distribution, like There’s Always Vanilla the film disappeared for decades, concealing Romero’s stylistic and thematic experimentation as he felt his way towards a more clearly defined personal approach to filmmaking.

In this, he made a big leap forward the following year by returning some way towards the roots he’d planted in 1968. In terms of material, The Crazies (1973) may seem like a step back after the previous two character-based dramas; the new movie reworks the zombie holocaust on a larger scale and in colour, though here the threat is not actually the revived dead but rather a small town’s population contaminated by a biological weapon; the cosmic horror of NotLD is supplanted by a post-Watergate cynicism about a government which thinks nothing of victimizing its own citizens. Some of the social commentary of NotLD had been accidental – the significant casting of Duane Jones as Ben had added a complicated critique of race which had not been a part of the original conception, for instance – but the politics of The Crazies is clearly embedded in the script, laying the groundwork for Romero’s breakthrough epic Dawn of the Dead (1978), which uses the zombie apocalypse for a blackly comic dissection of social fragmentation through rampant consumerism. But that was still five years in the future.

Once again, poor distribution hampered Romero’s progress and for the next three years he worked on a series of sports documentaries and industrial films (including the recently unearthed The Amusement Park [1975]), forging critical relationships with producer Richard Rubinstein and cameraman Michael Gornick, both of whom would work with Romero on every project up to Day of the Dead (1985). Emerging from these years, Romero returned to his independent roots – a tiny budget and a small, dedicated cast and crew – to make what would remain his most personal film (and his own favourite).

Martin (1976)

Martin (1976) is in many ways the most sophisticated film of Romero’s career, an almost encyclopedic summation of a particular core thread of the horror genre which builds layer upon layer of narrative tropes and themes to explore the figure of the vampire from multiple angles. Romero brings to bear all his skills as a filmmaker to create a masterpiece which, once again due to limited distribution, was not widely seen, though it’s always had a fairly positive critical reputation. Inevitably, given its modest scale and intimate story, it has long been overshadowed by Dawn of the Dead, which was released just over two years later.

I first saw Martin in 1979, when it was screened at the University of Winnipeg. In fact, I went to see it twice because it impressed me so much. Even seeing Dawn of the Dead several months later didn’t diminish my appreciation – in fact, like Romero, I consider it his finest film. I saw it once more in a theatre a couple of years later, a confusing experience as in Hong Kong it was screened in Dario Argento’s re-edited version Wampyr, which rearranged the order of sequences and replaced Donald Rubinstein’s haunting score with music by Goblin. That rather scrambled my memory of the film until I bought a copy of Anchor Bay’s DVD release in 2000. Given the nature of the original material (it was shot on 16mm reversal stock), the film has never fared well on DVD, so for its admirers the new 4K restoration by Second Sight in England is very good news.

Watching it again in what is surely the best quality possible confirms its position as a key film in Romero’s uneven body of work. The camerawork and editing are excellent, managing a potent combination of bleak naturalism and romantic expressionism in which the reality of a dying town and the fantasies with which Martin makes the horror of his own actions bearable play off each other in complex ways. As viewers, we are caught between these expressive modes, drawn to Martin despite being repelled by his actions. Here, Romero delves into the paradoxical appeal of monsters which can too easily tip over into a problematic identification with a killer at the expense of sympathy for his victims.

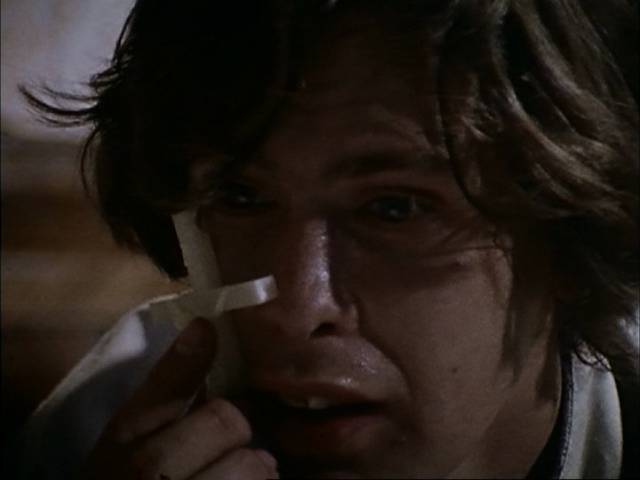

Romero establishes these conflicted feelings in the opening sequence. Martin (John Amplas) boards a train, having already selected a victim, a woman travelling alone. As the train moves off into the night, he prepares his tools – a syringe full of a tranquilizer, a razor blade – and picks the lock of the woman’s sleeper compartment. Martin’s edgy focus, working quickly for fear of discovery, is transformed by his own fantasy version of the situation: in expressionist monochrome, with tilted camera angles and emphatic editing which heightens the sense of romanticism, he becomes a forceful, desirable antihero, the vampire of classical cinema who arouses desire in his victims. By cutting back and forth between this self-image and the more sordid reality, Romero amplifies the horror of Martin’s actions as he drugs the woman and struggles with her, absurdly pleading for her to calm down because he doesn’t want to hurt her.

When she finally succumbs to the drug, he strips her and himself and enacts a pathetic simulation of an intimate embrace before using his razor blade to slice open the artery in her wrist, blood spilling out as he presses his mouth against the wound to drink. It’s clear that Martin is impotent and has devised this violent method to achieve erotic satisfaction, protecting himself from the horror by transforming the situation into a fantasy rooted in movies. (Some readings of the film suggest that the expressionistic black-and-white sequences represent Martin’s memories, confirming that he really is an eighty-plus-year-old vampire, but since they recast scenes in which he’s currently engaged as alternate, romanticized versions, it seems clear to me that they are actually a subjective overlay on what is actually happening, shaped by Martin to distance himself from his own actions.)

In just these first few minutes, Romero has established the psychological ground on which everything which follows rests. He weaves together so many threads into a virtually seamless pattern that I’ll try to separate some of them here to examine just how rich the film is.

The setting: Romero always had a fine sense of location and the ways in which place informs narrative meaning. That train in the opening sequence is carrying Martin towards Braddock, Pennsylvania, a dying town in the rust belt. Having lost its primary industry (steel), its residents cling to the place which once shaped and supported their lives. Martin, a harbinger of death himself, lands in a community overshadowed by a form of social and economic death haunted by people who don’t quite seem to realize that their own lives are essentially over.

The killer: little more than an adolescent, dislocated and impotent, Martin is all too aware of his own impotence, fearful of sexual intimacy yet yearning for some connection. He’s an early example of what we’d now call an incel, longing for something and bitter that it seems to be withheld from him. Unable to enter a relationship with a woman on equal terms, he uses violence to subjugate his victims and enforce a twisted parody of intimacy.

The myth: although Martin might well have become a killer anyway, the particular nature of his crimes is rooted in the specific circumstances into which he was born. His family roots go back to a superstition-burdened Eastern Europe, with those superstitions dragged into the New World; family elders believe that they live under a curse, with certain members born as vampires who must be first saved and then destroyed. Martin, rather than a confused boy, is supposedly an old man born in the 1890s, sent now to live with his cousin Cuda (Lincoln Maazel), who has been given the task of dealing with the curse. Ironically, even Cuda’s conception of the curse is coloured by the movies as he calls Martin “nosferatu” and hangs garlic and crucifixes around the house. The family has guided Martin’s madness into the particular expression it takes, transforming his sexual insecurity and confusion into this grotesque parody of pop culture vampirism.

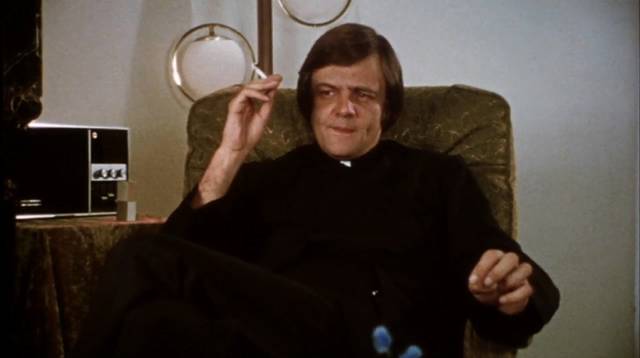

Religion: while Cuda clings to his old world views with his belief in what Martin disdainfully calls “magic”, religion in Braddock has lost its spiritual trappings. The church to which Cuda insists on dragging Martin is currently situated in a rundown loft, the actual church building having burned down (Romero once again taking advantage of location as there’s an actual gutted church available as background). At the service, Father Howard (Romero himself) foregoes the sermon in favour of a plea for donations as funds are needed to finance rebuilding. Later, Father Howard comes for dinner, more interested in Cuda’s wine than religious debate. He chuckles uncomfortably when asked if he believes in actual evil, and comments that he really enjoyed The Exorcist. The priest seems disappointingly devoid of traditional belief, seeing his role more as a community organizer than a spiritual guide; at Cuda’s prompting, he recommends another older priest, Father Zulemas (J. Clifford Forrest Jr.), as someone who still believes in “the old ways”, and Cuda invites him round to exorcise Martin, a decidedly ineffectual gesture.

Reality vs fantasy: a lot of reviews describe the film with a touch of condescension as “arty” or even pretentious, but to some degree this comes from a position which believes that low-budget horror movies shouldn’t try to rise above their station. By playing with different cinematic registers, however, Romero adds genuine depth to the film. His treatment of the social and economic realities of the town – embodied by Cuda’s granddaughter Christina (Christine Forrest) and her bitter boyfriend Arthur (Tom Savini), who have no viable prospects and are desperate to move away – and the bleak atmosphere which feeds Martin’s depression amplifies the boy’s madness and drives his compulsion to find release in violence. But the strain of killing is almost unbearable, which is why he attempts to transform his actions by recasting them as a romantic form of horror, effectively rendered by Romero as scenes from an old movie. Martin draws on pop culture myths both to give shape to his actions and to distance himself from the appalling reality of what he does. Ironically, these expressionist scenes seemingly set in the past also serve to suggest that he is in fact an eighty-three-year-old man who has been preying on willing victims for decades.

The murders: given the intricate play with vampirism in its multiple registers, it’s easy to skim over the fact that Martin is actually a serial killer movie. This is a problematic genre, all too often valorizing the monster who is so much smarter and more clever than his (almost always a him) victims and those pursuing him. Victims are often vague and undifferentiated, mere material on which the killer leaves his signature – this dehumanization all too often forcefully aligns the viewer with the killer’s point of view. Romero plays with this tendency in interesting and unsettling ways through the interlacing of reality and Martin’s fantasies. The jarring disconnect between his romanticized self-image and what he’s actually doing hammers home the horror of his actions; casting himself as a romantic figure welcomed in by his victims tempts the viewer to identify with his view of the world, and the quotidian depiction of life in Cuda’s house and the decaying town surrounding it does draw us into alignment with Martin. We empathize with his awkwardness, his loneliness, his hopelessness. But Romero also gives us a powerful counterweight in the objective depiction of the killings. Martin’s method is so obviously well-honed that it’s clear that he has done this many times before; he comes prepared with syringes and razor blades and carefully removes his own clothes to avoid bloodstains. In the second murder sequence, we see him planning for days, observing his chosen victim’s routines, buying necessary equipment, waiting for her husband to leave on his business trip; we have been lulled by his awkward ordinariness and go along with him, implicated in his actions despite the lingering memory of that first brutal scene on the train. There’s little time for us to “know” the victims, and yet Romero manages to humanize them and convey the horror of what they’re being subjected to. On the train, as his victim begins to succumb to the drug, and he pleads with her to stop struggling and just go to sleep, she contemptuously calls him a “freak rapist asshole”, a blunt refutation of his self-image and a refusal to comply with the role he has absurdly tried to assign to her. Romero situates the viewer in an uncomfortable and irresolvable contradictory position where the empathy we may feel through much of the film becomes untenable; how are we supposed to position ourselves in relation to this character, and by extension to all such monsters who populate our entertainment?

Redemption: as the film progresses, it offers a tentative counterpoint to the family myth which has trapped Martin in this cycle of violence. Put to work by Cuda as a delivery boy for the family grocery store, he meets housewife Mrs. Santini (Elyane Nadeau), an unhappy woman who seems to recognize a kindred spirit in the lonely, silent, depressed boy. She asks him to come and do some handiwork around the house where she lives in a kind of stasis, left alone every day as her husband goes to work. At first, Martin flees in fear, but eventually he’s drawn to what she seems to be offering and he finally has his first consensual sexual experience. But this boy, considerably younger than herself, can’t dispel her depression; Martin’s brief moment of tenderness with Mrs. Santini ends up reinforcing his distrust of the “sexy stuff”, confirming that such intimacy is not a viable substitute for his thirst for blood.

The media: while old movies help Martin to define his identity, a more modern form of media provides him with a way to explain and justify himself. When Christina has a phone installed in his room, he begins calling in to an all-night radio show to explain what it’s like to be a vampire. The host eats it up and eggs him on, gradually building a kind of fan base for “the count”. But this, rather than providing a kind of therapy, merely reinforces Martin’s false identity. There’s no escaping the role imposed by the family myth and reinforced by his own murderous pathology which he has conformed to that myth, and the media reduce his torment to nothing more than disposable entertainment.

In the film’s final irony, placing it in the realm of tragedy, what ultimately destroys Martin is that brief moment of tenderness with Mrs. Santini; unable to cope with her depression and a sense of guilt over what she’s done with the young, insecure boy, she commits suicide and Cuda assumes that Martin has taken her life, violating the one rule he was given when he arrived. Unable to save Martin’s soul, Cuda destroys him with a very traditional stake through the heart, burying him in the yard as his radio fans continue to believe in him.

*

Romero’s script for Martin is his richest piece of work and he realizes it on screen with some of his best filmmaking. The blend of social realism, graphic horror and psychological drama give it a tonal complexity which is further enriched by a streak of dark comedy. The set-pieces in which Martin commits his murders are horrific, yet the ways in which the reality fails to match his intentions and the fantasy version of events he conjures to make his own actions bearable edge the film into black comedy. On the train as he bursts into the sleeping compartment, envisioning a negligee-clad woman greeting him with open arms, he finds it empty and a moment later hears the toilet flush and the woman emerges with her face caked in cold cream. The ensuing struggle is clumsy and depressing, her waning resistance as the drug takes effect giving way to fear which he tries to mitigate with obvious lies about not wanting to hurt her.

Even more elaborate is the later attack on a suburban home where he discovers that his intended victim, expected to be alone as her husband is away on business, is in bed with a lover; Martin has to improvise to deal with two people, the man initially trying to placate him because he assumes Martin is the woman’s husband unexpectedly returning early. Here Romero is at his best, choreographing the complicated action with skill while also weaving in Martin’s subjective vision of events by refracting each moment through imagery from the movie in his head.

Through Romero’s layering of ideas and narrative elements, the film intricately conflates three separate conceptions of the vampire. There’s the modern serial killer whose sexual compulsion includes drinking the blood of his victims; the traditional monster of European folklore surrounded by religious superstition; and the romantic figure of popular culture rooted in Nineteenth Century literature and Twentieth Century movies which used vampirism as a metaphorical device to sneak sex past the censors. All these layers come together in Martin to create a complex, even tragic narrative about a sexually confused young man who finds himself trapped in an identity he can’t fully comprehend which drives him to commit terrible acts by which even he is appalled.

*

Second Sight have done an excellent job with their 4K restoration of the film. As mentioned, Martin was shot on 16mm reversal stock (with the transfer here taken from a 35mm blow-up internegative) which means that the image has dense grain and pronounced contrast. Given the gritty nature of the story, the unpolished image is entirely appropriate and definitely looks richer and more detailed here than on earlier DVDs. It’s presented full-frame at 1.37:1, which preserves the originally intended composition – some DVDs cropped it to 1.85:1, but that compromised the framing.

The film comes in a three-disk set which includes a 4K UHD copy, a region B Blu-ray and a CD of Donald Rubinstein’s score.

Extras include two archival commentaries with Romero and various cast and crew members, plus two new commentaries from Kat Ellinger and Travis Crawford. Along with a brief archival making-of (9:34) and several trailers and radio spots, there’s a new retrospective (69:15) in which key members of cast and crew look back on the production, including a walking tour of the locations in Braddock; an interview with Donald Rubinstein about the score (17:30); and a short documentary by crew member Tony Buba shot in Braddock in 1974 (11:13).

The set comes in a sturdy slipcase with a 100+ page book containing a dozen essays on the film.

Like Second Sight’s superlative edition of Dawn of the Dead, Martin is only available in the UK so once again I had to use a bit of subterfuge to obtain a copy through a friend in London, but it was well worth the trouble and expense. Romero’s finest film has finally been given the release it deserves.

*

One tantalizing piece of information gleaned from the extras is that the long-lost “director’s cut”, a print which disappeared before the film was completed and released, reflecting Romero’s desire for it to be seen entirely in black-and-white, may have resurfaced last year. No details are given, and obviously Second Sight were unable to access it for this release – but the prospect of finally being able to see this longer version at some point is really exciting! But who knows when and if that will be possible: I did find this puzzling listing for an on-line auction from last July in which someone apparently paid $51,200 for the 16mm print, though there’s no indication of who bought it, or who was selling it (did they have any rights to it, since it was Romero’s own copy which disappeared back in the mid-’70s?). It would be depressing to think that it was bought by a collector who wants to keep it for themselves, but the lack of any announcement from a company planning a release is troubling.

Comments

Kenneth,

thanks for the great review of this film! As always, your review is thorough and insightful.

I have most of Romero’s films in my collection and Martin is definitely one of the best vampire films I’ve ever seen.

It’s a shame Romero didn’t have the mainstream recognition that he deserved. There were other regional filmmakers that could have had a major career but things just didn’t gel for them. Herk Harvey comes to mind. It’s amazing to me that he only made one film- Carnival of Souls.

Carnival of Souls is definitely a favourite, as is Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural, another lone feature by a filmmaker who inexplicably didn’t make any others. As for other vampire films from that period, John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire ought to be much better known.

I definitely have to watch those two vampire movies. I checked out the plots and they sound like great films. I’ve never heard of them before of course. Thanks for mentioning them!

What a remarkable analysis of “Martin”! This article brilliantly highlights the complexities of George A. Romero’s masterpiece, delving into its rich thematic depth and profound social commentary. It’s evident that the author has a deep appreciation for the film and a keen eye for its nuances. The writing style is engaging and insightful, making it a pleasure to read. Thank you for this captivating piece, it truly does justice to Romero’s visionary work. – Gary Ford