Styles of Horror, part one

I’ve been watching a mix of old and new movies this past month, some old favourites and a few new discoveries (of uneven value). Horror seems to predominate for some reason. Scream Factory has become a reliable supplier of older genre titles (though a few are maybe best forgotten). I’ve gone through their four-disk, six-movie Vincent Price Collection, welcome editions of Paul Schrader’s Cat People and George A. Romero’s Day of the Dead, and the less welcome James Isaac potboiler The Horror Show. Slightly more esoteric are Liliana Cavani’s I cannibali (Year of the Cannibals) from Raro Video, David Rudkin’s ambitious BBC play Artemis 81 (directed by Alastair Reid), and Bill Gunn’s radical confrontation with blaxploitation, Ganja and Hess.

Beneath (Larry Fessenden, 2013)

But to start, one of the month’s big disappointments is Larry Fessenden’s first directorial effort since The Last Winter in 2006. That movie, only his fourth as director in fifteen years, confirmed Fessenden as a thoughtful filmmaker who uses genre as a vehicle for serious ideas – the Frankenstein-inflected exploration of the morality of vivisection and genetic manipulation in No Telling (1991); vampirism as a metaphor for emotional addiction within unstable urban relationships in his masterpiece, Habit (1995); and with Wendigo (2001) and The Last Winter (2006), an expanding exploration of nature and the human place within it, the damage we do to each other and to the world we inhabit.

But this sparse list belies just how busy Fessenden has been in the past two decades; through his company Glass Eye Pix, he’s shown himself to be something of a mini-mogul, producing and helping to produce a wide range of films, from a lot of low budget horror which exhibits a similar strain of intelligence to his own work (Ti West is one of his proteges) to Rick Alverson’s divisive The Comedy to Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy. It almost seemed that Fessenden had given up directing for producing exclusively, so I was very interested to see a new feature announced last year … and when the really bad reviews started appearing, I was willing to believe that people were misreading the movie, that Fessenden must be using the tropes of stupid teen horror to explore something more interesting.

Alas, with Beneath (the first of his features he hasn’t written himself; the script is by Tony Daniel and Brian D. Smith, whose only previous writing credit is the equally awful Flu Birds) it’s impossible to see why Fessenden bothered to make the effort. The set-up is so conventional that you keep waiting for it to twist into something else, but it never does. Six school friends, celebrating graduation and the imminent start of a new phase of their lives, head off to a remote lake for some fun. There are inevitable tensions (one of the girls was once with one of the boys, but has since switched to the biggest jerk in the group; another boy annoys everybody by insisting on taping everything with his video camera). There are hints that the brooding Johnny (Daniel Zovatto) knows that there’s some danger hidden in the lake, and possibly the implication that he’s led the others here to get some kind of revenge on a really annoying peer group. Anyway, they all end up stuck in a small boat in the middle of the lake as a giant flesh-eating fish picks them off one by one. The business among the characters is endlessly tedious; the big fish is an often hilarious mechanical effect. But worst of all, Fessenden brings nothing to the bare bones story beyond those bare bones – this isn’t even a send-up of stupid teen monster movies; it’s played so unimaginatively straight that the viewer’s sense of despair very quickly outruns that of the characters as they face their inevitable deaths.

*

Day of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1985)

I think I was first made aware of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead through a film review column in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the early ’70s (probably written by Baird Searles), in which readers were urged to make an effort to see the film if it played anywhere within a hundred miles of where they lived. I actually drove the hundred-and-fifteen miles from Neepawa to Winnipeg to catch a screening at the Planetarium, part of their summer series of horror movies in 1974. It was well worth the trip. Catching a screening of The Crazies a few years later, I became a confirmed fan; Romero was an incisive writer, a skillful director and a superb editor. He didn’t just shoot scenes, he carefully constructed them for relentlessly building impact (using far more shots than was typical in low budget genre movies at the time); he was a master of detail and emphasis, and his scripts were actually about something – typically a bleakly humorous view of the ways in which human beings consistently work against their own best interests because petty conflicts outweigh the larger dangers threatening them. Then came Martin, his masterpiece, one of the finest dissections of the vampire myth ever put on film, looking at it as both pop culture myth and terrifying psychological aberration. With Dawn of the Dead, he came up with a genuine epic of horror and black comedy, a rich, funny, disgusting, frightening slap in the face of soulless consumer culture dressed up in rotting zombie clothes. Released unrated because the MPAA objected to the extremity of Tom Savini’s gore effects, it became a worldwide hit and triggered a multinational vogue in zombies which hasn’t let up in three-and-a-half decades (there would be no Walking Dead or World War Z if Romero hadn’t made Dawn).

After Dawn, Romero was offered financing for three features by exhibitor Salah M. Hassanein, who wanted an immediate repeat of Dawn to cash in on the film’s success. But Romero resisted being pigeonholed and went in an entirely different direction with perhaps his most personal film, Knightriders. This retelling of the story of the Round Table follows a group of bikers who put on renaissance fair demonstrations of motorized jousting while struggling with personal conflicts, issues of integrity, and the pressures of an increasingly commercialized society. Audiences were baffled and reviews were not very good; distribution was spotty and returns disappointingly low. Which is too bad, because Knightriders is a terrific modern parable, made with all the skills Romero had at his command. (It’s interesting to note that just a couple of years earlier, David Cronenberg also pushed against being pigeon-holed with Fast Company, a somewhat similar movie about racers resisting the pressures of commercialization which threatened to undermine their integrity and ruin the sport they loved.)

The decision the next year to team up with Stephen King for Creepshow seems like one of the most deliberately commercial of Romero’s career. An anthology movie in the vein of Amicus’ series from the mid-’60s to the early ’70s, it was lighter than the previous films, aimed at a broader more kid-friendly audience. Although Romero’s most expensive film to date, it grossed far less than the unrated Dawn, and so for the third movie of his contract with Hassanein, the director returned to the saga of the living dead. But there was less money available now and it wasn’t possible to produce the epic-scaled movie he had originally planned, expanding beyond Dawn to depict a whole world over-run by zombies. However, that might not have been a bad thing; forced to pare down his script, Romero came up with his bleakest, most intense and concentrated effort since the original Night.

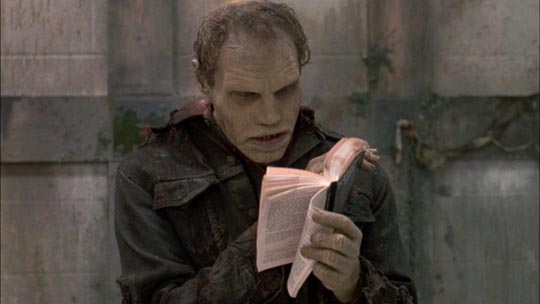

I was puzzled even back in 1985 by the air of disappointment which greeted Day of the Dead. It seemed odd to me that people disliked the movie because it wasn’t a replay of Dawn; I liked its darkness and appreciated that it played more directly as horror than satire (although there are still satirical elements). A claustrophobic story set in a complex of remarkable caves (the Wampum Mine in Pennsylvania), it shows a small group of survivors going mad from the pressures of their world coming to a violent end. A handful of scientists struggle to find a “cure” for the zombie plague while their military minders, who only understand fighting and killing their enemies, increasingly become a threat to the team. Not that the scientists themselves are too rational any more; the head of the team, Logan (Richard Liberty), dubbed Frankenstein by the soldiers, turns out not to be looking for a cure, but rather trying to find ways to modify the zombies’ behaviour. Strangely, as the film develops, the most sympathetic character turns out to be Bub (Howard Sherman), one of the dead in whom Logan awakens memories, beginning to restore his humanity (a thread which Romero would continue to explore in his subsequent zombie trilogy, Land, Diary and Survival of the Dead).

The film was criticized at the time for being over-the-top and hysterical, but given the situation facing the characters that intensity seems justified. As always in Romero’s films, the acting is better than we often see in low-budget genre movies, and his construction and control of the atmosphere of escalating tension is impeccable. As in Dawn, he again places a strong woman at the centre of the story; Sarah is played by Lori Cardille, whose father, “Chilly Billy” Cardille, was a Pittsburgh broadcaster who played the TV reporter in Night of the Living Dead. And once again, Tom Savini’s gruesome effects are imaginatively designed and convincingly executed (in fact, Day probably represents Savini’s finest work[1]).

Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray gives the film its best appearance yet on disk, and includes most of the extras from the old Anchor Bay special edition DVD, plus a feature-length making-of which interviews a lot of the people involved in the production. Hopefully the disk will further redeem the reputation of one of Romero’s finest films.

*

Cat People (Paul Schrader, 1982)

When Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur were handed the title Cat People in the early ’40s and told by RKO to turn it into a B-movie, working from a script by DeWitt Bodeen they transformed a pulp idea into one of the most revered and subtle fantasies in Hollywood history. The story of an ordinary man who falls in love with a foreign woman who fears that, due to an ancestral curse, sex will transform her into a monster, it relied on mood and suggestion to convey ideas which the Hays Office would certainly have frowned on if addressed directly in a non-horror context.

When Paul Schrader agreed to undertake a remake in the early ’80s, working from a script by Alan Ormsby (Bob Clark’s Dead of Night and Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things and Jeff Gillen’s Deranged), with the relaxed censorship atmosphere of the time, he embraced the pulpiness of the story and made explicit what had been implicit. The sex and gore of Schrader’s version is given free rein, with some additional fillips like incest, hookers and oral sex. At the time, much of this was seen as sacrilege, an affront to the Lewton philosophy of subtle indirection; but Cat People ’82 is its own creature and succeeds very well as a perverse fantasy rooted in Schrader’s Calvinist puritan sensibilities. Sex here is a very real danger and giving into its urges transforms Irena (Nastassja Kinski) and her brother Paul (Malcolm McDowell) into savage panthers who must kill and eat their lovers in order to regain human form. The only way to avoid the horror, Paul assures Irena, is for brother and sister to mate exclusively with each other.

Set in New Orleans, atmospherically designed (with input from Ferdinando Scarfiotti) and steamily shot by John Bailey, the film has an overheated mood in which sex, danger and death are inextricably intertwined. Schrader handles the erotic and horror elements with equal skill, playing it all straight so that the essentially risible core possesses a conviction which carries the viewer along for the duration; it’s only after the fact that you have time to consider the creepily conservative implications of the story – Schrader came up with the eventual ending, scrapping Ormsby’s conventional conflagration which restores normalcy to the world. In the film, we get a lingering bondage scene in which hero Oliver (John Heard) makes love to Irena, transforming her again into a cat, and then keeps her locked up in a cage at the zoo where he works, the deadly threat of female sexuality contained under his own authority …

Cat People looks terrific on Shout! Factory’s Blue-ray, but the supplements consist only of seven short interview clips with Schrader, Giorgio Moroder (composer of the excellent synth score), and the five main actors: Kinski, McDowell, Heard, Annette O’Toole and Lynn Lowry.

____________________________________________________________

(1.) The first home video copy of Day of the Dead that I owned was a used VHS tape from a local video rental store. It was a Canadian release and turned out to have been made (pan-and-scanned of course) from a print which had been censored in Ontario (even as recently as a decade ago, Ontario was still ordering cuts in movies instead of simply classifying them, and maybe they still do). The tape wasn’t just a visual disappointment (murky, cropped images); instead of deleting specific “offensive” scenes, the censors had actually cut out virtually every frame of Savini’s gore effects, resulting in numerous jump cuts in many scenes which rendered the action, and at times the dialogue, utterly incoherent. (return)

Comments

Just fyi, since the advent of DVD you can buy the uncensored Day of the Dead in Canada, as with most horror films – but the Canadian government still paternalistically reviews material sent into Canada and sometimes bans it. Very entertaining pdfs of material banned in Canada can be found at gomorrahy.com, along with some pretty crazy trailers and such.

Yes, I was talking about the old days of videotape and intrusive censorship. It’s pretty easy now to get hold of anything you want uncut, either locally or over the Internet. There’s no national standard with regard to movies as each province has its own ratings board — and for the most part that’s all they do now, give movies a rating.