Another eclectic week

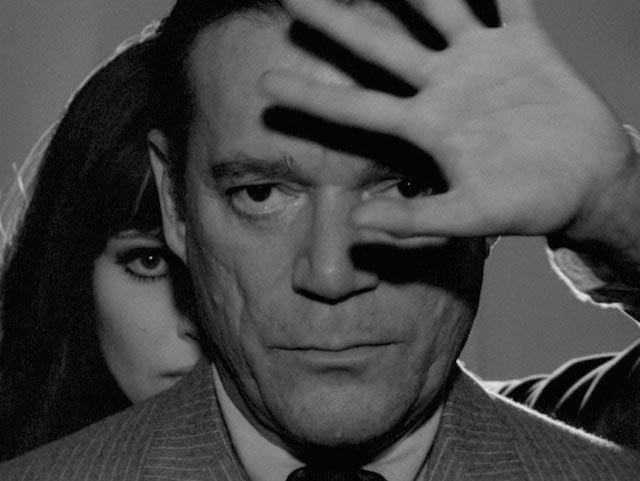

in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965)

As I continue my recovery, I’m still watching a lot of less demanding (and perhaps too frequently trashy) movies. The best of them tend to be older films, reminding me that our tastes and preferences are established early and stick with us throughout our lives. As I’m sure I’ve mentioned here a number of times before, I was lucky enough that my own formative years were at a time when television provided regular access to a broad range of film history, making movies from the silent era on up to the present contemporary for me. My friends who teach film have often told me that their students’ prior knowledge generally only goes back a couple of years … and many of them show little interest in or enthusiasm for the history of the subject they’ve supposedly chosen to study.

The oldest of the movies in the current group was made in 1945, and represents something of an experiment by Ealing Studios as the company emerged from the War. Having produced some of the finest propaganda features of the War – Thorold Dickinson’s The Next of Kin, Alberto Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well (both 1942), Basil Dearden’s The Bells Go Down (1943) among others – the company was exploring new directions. They had already dabbled in fantasy and even allegory in Basil Dearden’s The Halfway House and They Came to a City (both 1943), the former a ghost story dealing with the weight of death borne by the people on the home front, the latter a Utopian fantasy about what might be made of the future once the conflict was over.

*

Dead of Night (Basil Dearden, Alberto Cavalcanti,

Robert Hamer, Charles Crichton, 1945)

Dead of Night (1945), although not considered as such when it was made, was one of the first and most sophisticated horror films produced by the British film industry. The War is nowhere mentioned, although embedded in the narrative structure is the idea of renewal … and dark forces which are at work to thwart it. It begins with the arrival of architect Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns) at an old farmhouse whose owner, Elliot Foley (Roland Culver), wants to hire him to renovate and modernize the place. Craig is overwhelmed by an uncanny feeling that he has been here before and met Foley and his guests … he can recount details about them, things they are about to say or do, setting off a discussion about reason and the uncanny, with each guest offering a story of their own experiences with ghosts and the paranormal.

Dead of Night established the template for every horror anthology to come, and as with most examples of the genre the individual narratives are uneven in tone and impact. However, where this film excels – and has never been bettered – is in the dramatic power and effectiveness of the framing narrative. Directed by Dearden, it’s far more than a device to hold together a bunch of unrelated stories. It gradually builds towards an ominous and ultimately bleak conclusion, with Craig seemingly doomed to relive the same events over and over forever. Perhaps more importantly, Dearden skillfully modulates the tone of the interactions among the guests, making the transitions in and out of the stories dramatically meaningful, binding them all together into a coherent whole.

Judged on their own terms, the five embedded stories vary from traditional ghosts to psychological horror to apparent whimsy. The latter, Charles Crichton’s “Golfing Story”, is often dismissed as inappropriate and disposable, but watched closely it reveals a surprisingly disturbing undertone and more than any of the others seems to allude to the way in which death during six years of war has unsettled traditional social relationships. That a brief story which includes suicide and the dissolution of marital propriety comes across as a lightly comic trifle about an inexperienced ghost bothering his friend on his wedding night is a sign of the overall film’s sophisticated play with tone and viewer expectations.

Cavalcanti’s “Christmas Party” and Dearden’s “Hearse Driver” are the most conventional segments, both featuring a ghostly encounter which suggests the folding of time, which emerges as the whole film’s defining structure. The darkest and most complex stories are Robert Hamer’s “The Haunted Mirror” and Cavalcanti’s “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy”. In the former, a woman (Googie Withers) gives her fiance (Ralph Michael) an antique mirror which reveals to him a past event in which a jealous husband killed his wife; the fiance is gradually taken over by the malevolent emotions captured by the mirror and comes close to repeating the crime it has recorded. (Hamer immediately built on this short film’s atmosphere and themes in two superb post-war features, Pink String and Sealing Wax [1945] and It Always Rains on Sunday [1947], both starring Withers.)

Cavalcanti’s climactic contribution remains the most famous and influential story in the anthology. Michael Redgrave gives a remarkably subtle and intense performance as a man losing himself to the influence of his own malevolent puppet. This is the urtext from which derive all subsequent stories in which multiple personalities project their darker selves into inanimate objects which come to life and act out murderous intentions. And no one – not even Anthony Hopkins in Richard Attenborough’s Magic (1978) – has equaled Redgrave’s chilling evocation of this kind of madness.

Dead of Night was a showcase for four of Ealing’s key directors, but just as important was the opportunity it afforded the studio’s technicians to create a variety of styles in production design, photography and optical effects … everyone went on to help create the great variety of movies which made Ealing such a significant part of post-war British cinema.

Given the significance of this film, it’s a great pity that the original elements are apparently lost. Although it’s good to have it on Blu-ray, and no doubt Kino Lorber have done the best they can with available materials and resources, it’s impossible not to be at least a little disappointed by the uneven image quality, with frequent softness and significant print damage – not just a great deal of dirt and speckling, but large and distracting scratches which at times run through entire scenes. In addition, the sound is thin and tinny, with dialogue at times not clearly audible. This film is in dire need of a major restoration effort and hopefully at some point better quality materials will be unearthed.

But even despite these technical issues, the disk is a really worthwhile acquisition, both for the film itself and for two substantial extras: a typically well-informed commentary from Tim Lucas and a feature-length historical and critical discussion of the film by a number of critics and filmmakers who do a great job of illuminating what makes it so special.

*

Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

Jean-Luc Godard, who began as one of the most influential Cahiers du cinema critics in the 1950s, was a theorist from the start, something that became particularly obvious in the late ’60s when his work became overtly political. In his early films, from Breathless (1960) to, say, 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967), politics was subsumed by an intellectual interest in cinema itself, the mechanics through which meaning is communicated. Those years were marked by a sense of curiosity and play as Godard enthusiastically deconstructed and reconfigured genres, from romance and gangster movies to melodrama and war films.

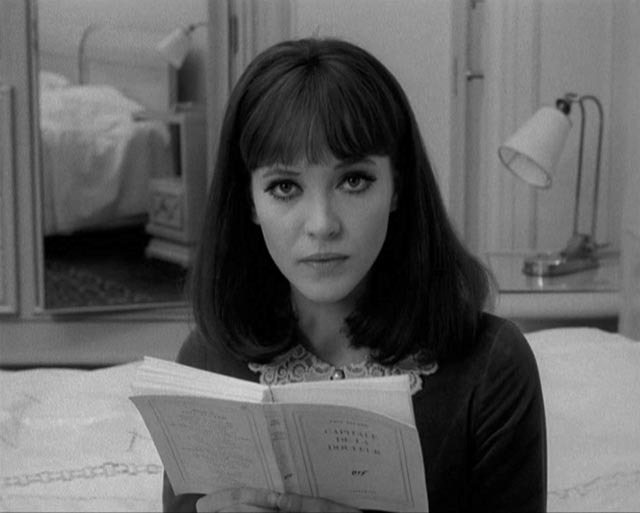

One of his most playful and inventive movies of this period is Alphaville (1965), a profligate mixture of multiple genres wrapped in a pulp sci-fi wrapper. Exquisitely shot on Paris locations in high-contrast black-and-white by the great Raoul Coutard, it’s a film noir set in an alternate reality only slightly removed from our own. Eddie Constantine reprises his role as secret agent Lemmy Caution from a long series of B-movies, bringing all the hard-boiled cliches with him to a city ruled by a super computer, Alpha-60, created by renegade scientist Professor von Braun (Howard Vernon). In an ambitious attempt to create a purely rational society, von Braun and his machine have stripped language of every vestige of emotion, transforming the city’s occupants into automata whose speech has become abstract to the point of surrealism.

Caution strong-arms and shoots his way through the city, his crude animal violence gradually waking von Braun’s daughter Natacha (Anna Karina) from her somnolent state as he closes in on her father and Alpha-60. He eventually gets the machine to self-destruct by speaking to it with poetry and the language of emotion. Which is to say that Godard has constructed Alphaville out of the hoariest cliches of pulp magazines, comic books, science fiction, spy movies and film noir. But all these, and other genres, are built from familiar narrative bits and pieces – in movies, what always matters is how the filmmaker uses the raw materials culled from sources high and low.

In Alphaville, as in something like 2001: A Space Odyssey (released just three years later), what matters is the director’s use of imagery and sound to create a coherent world similar to our own yet different enough to open the viewer’s mind to seeing from a new and unfamiliar angle. A reduction of such a film to its base narrative points can’t possibly convey the actual experience of watching it; Godard’s movie is an exhilarating mix of pulp and poetry, laced with an entertaining streak of dead-pan humour, making it one of his most enjoyable and satisfying experiments from the first phase of his career. As such, it ranks with Le mèpris (1963), Bande à part (1964), and Pierrot le fou (1965).

Kino Lorber’s new Blu-ray is mastered from a 4K restoration and Coutard’s images look absolutely gorgeous. The soundtrack, so important to the film’s impact, is equally strong, with clear voices and a dynamic presentation of Paul Misraki’s wonderfully dramatic score. (There’s also an English dub which, surprisingly, isn’t too bad.) The disk includes a brief introduction from Colin McCabe and a short interview with Anna Karina, plus another informative commentary from the very busy Tim Lucas.

*

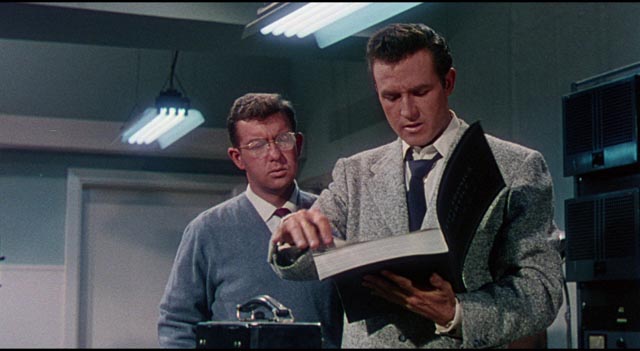

This Island Earth (Joseph Newman, 1955)

I recently revisited two old favourites from a slightly earlier, less self-conscious era, when genre tropes were accepted at face value and put towards strictly commercial ends. Both were produced by Universal, a studio which had secured its place in pop culture with its classic horror films of the 1930s, plunging into territory the more respectable studios shied away from. Universal was a little slow to join the sci-fi boom of the early ’50s, but when they did they had an immediate string of low-budget successes thanks to producer William Alland and director Jack Arnold. Yet, despite Alland being in charge, when Universal decided to make something bigger and more prestigious, Arnold wasn’t involved. Instead, the assignment went to Joseph Newman, a nondescript talent whose work largely consisted of B westerns and crime movies with the odd comedy thrown in.

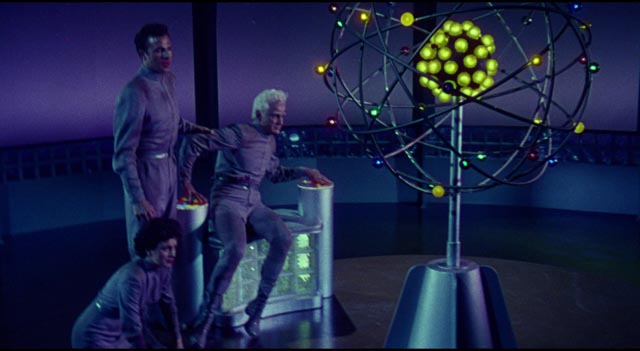

This Island Earth (1955) is mostly known to modern audiences, if at all, as the undeserving target of the smug, condescending staff of Mystery Science Theater 3000, who did a hatchet job on the movie for their sole theatrical feature in 1996. Newman’s movie is deeply flawed, but it deserves more respect as an attempt to create science fiction on a large scale at a time when most SF movies were modest and Earthbound. It would take all the resources of MGM to produce the first really successful widescreen colour epic in the genre the following year with Forbidden Planet. This Island Earth suffers in comparison, but nonetheless has its own charms and, towards the end, some quite wonderful visuals.

Based on a novel by Raymond F. Jones, the script by Franklin Coen and Edward G. O’Callaghan, is awkwardly structured, cramming the epic parts into the final third, but the first two thirds are narratively interesting in themselves – at least to someone who grew up reading pulp sci-fi. The movie begins as a mystery, promising both revelation and adventure. Engineer Cal Meacham (Rex Reason) receives a mysterious catalogue containing unfamiliar technology; intrigued, he orders parts for a device called an Interocitor. He and his assistant build the complex machine without knowing what it is, but when it’s completed and switched on, they receive a message from a man with a suspiciously large forehead who calls himself Exeter.

Exeter (Jeff Morrow) offers Cal an opportunity to work on an amazing yet unspecified project. Against his assistant’s advice Cal accepts and boards a pilotless aircraft which takes him to a remote estate in Kentucky, where he joins a group of scientists from around the world who are working on a project to produce unlimited energy. Exeter is an affable host, but other members of the team are reluctant to speak openly with Cal, and the other big-heads seem a bit less friendly.

Despite all the resources provided by Exeter, Cal and Dr. Ruth Adams (Faith Domergue) spend their time trying to figure out what Exeter’s actual motives are. They finally find out when they attempt to escape in a small plane and are sucked into a big spaceship by tractor beam. The rest of the movie is pure spectacle as the pair are taken on a long space voyage to the besieged planet Metaluna, which is losing a war with another planet. The research program had been designed to bolster Metaluna’s defences, but it’s too late and Cal and Ruth get to witness the destruction of an entire world and its civilization, escaping at the last moment with Exeter’s help.

The weaknesses of This Island Earth are many, but they mostly stem from an unimaginative director, the inadequate budget, and a script obviously tailored to accommodate those financial limitations. It would certainly have benefited from a fuller development of the first two acts, drawing out the mystery of Exeter’s identity and purpose so that the shift in the third act wouldn’t be quite so radical and abrupt. However, although the dialogue is all pretty perfunctory, the performances are generally good, with Reason, Domergue and Morrow all treating it seriously.

The movie’s biggest strength is the work of cinematographer Clifford Stine and the visual effects crew who give the attack on Metaluna and the planet’s final destruction a sense of scale and grandeur previously unseen at the time. Scream Factory’s Blu-ray does justice to their work with a 4K scan – presented both open-matte and framed at 1.85:1 – and a restoration of the original stereo soundtrack. There’s a commentary track from effects specialist Robert Skotak, an audio interview with film music expert David Schecter, a making-of documentary, an interview with Luigi Cozzi, and Joe Dante’s Trailers From Hell commentary. It’s nice to see this movie, flawed as it is, given the respect it deserves.

*

traumatized Ginny Simpson (Linda Scheley) in John Sherwood’s The Monolith Monsters (1957)

The Monolith Monsters (John Sherwood, 1957)

Ever since I first saw it on television sometime in the 1970s, The Monolith Monsters (1957) has been one of my very favourite ’50s sci-fi movies. Set in Jack Arnold’s beloved southwestern desert, it shares structural similarities with Gordon Douglas’ Them! (1954) – an unknown menace out in the desert is killing people in mysterious ways and it’s up to the authorities to identify the threat and put a stop to it. There’s even a traumatized little girl who has seen the monster but is unable to speak about it.

What makes The Monolith Monsters different is the nature of the threat. It’s not a deadly radioactive mutant nor aliens, but rather a meteoric crystal which grows in contact with water and sucks all the silicone out of living tissue, effectively turning anyone it touches when active into stone. After heavy rains in the hills above a small town, the crystals grow and multiply, falling under their own weight and shattering, only to rise up and shatter again as if marching down the canyon towards the town.

Racing against time, geologist Dave Miller (The Incredible Shrinking Man himself, Grant Williams) has to figure out how the crystal works and what will stop it – not just to save the town, but also to save the life of the little girl, who is slowly turning to stone.

The Monolith Monsters fits nicely with Jack Arnold’s It Came From Outer Space (1953) and Tarantula (1955) in setting and tone, but he didn’t direct it; that task went to John Sherwood, the last of four features he directed in a long career as an assistant and second unit director. Arnold’s influence is clear (he has a story credit), but Sherwood’s work isn’t merely derivative. It’s a lean, suspenseful movie without a wasted moment, driven by a sense of urgency, which nonetheless allows room for little character details which make the escalating threat matter.

The movie looks very good on Scream Factory’s Blu-ray, with barely noticeable instances of dirt or print damage. It’s a modest production, but the photography of Ellis W. Carter (who earlier the same year had shot Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man) is excellent and the miniature effects and matte shots (photographed by Clifford Stine) are impressive. There are two separate commentary tracks, one with Tom Weaver and David Schecter, the other with film historian Mark Jancovich. For some reason, Scream Factory has included an ultra-wide 2.00:1 version along with the standard 1.85:1.

*

All four of these films have more class than some of the others I’ve been watching lately. The latter include Ed Hunt’s silly but entertaining The Brain (1988), about a town being taken over by an alien brain creature which possesses people through a subliminal TV signal with the aid of mad scientist David Gale (late of Re-Animator). Some local kids have to figure out what’s going on and defeat the endearingly absurd menace. (Scream Factory Blu-ray, with an absurd three commentaries – with director Hunt, actor Tom Bresnahan, and composer Paul Zaza – plus several interviews and a fan featurette)

Yet another mad scientist is responsible for small town mayhem in Michael Miller’s Silent Rage (1982), the first Chuck Norris movie I saw in a theatre back in the day. In a quest to find immortality, a doctor gives experimental drugs to a psychotic, who not only develops almost instant regenerative powers, but also goes on a homicidal rampage (kind of like George Eastman in Joe D’Amato’s Absurd [made the previous year]). The only thing standing between the town and disaster is Sheriff Norris, who almost meets his match. The pace is sluggish, dragged down by an excess of “comic relief”, mostly involving doofus deputy Stephen Furst. The best thing about the movie is Brian Libby as the bad superman. (No frills Blu-ray from Mill Creek)

And for something completely different, we have Jeff Maher’s Bed of the Dead (2019), an entire feature made in homage to George Barry’s Death Bed: the Bed that Eats People (1977). It takes chutzpah to look at something as absurdly original as Barry’s sole feature and try to duplicate it, but Maher surprisingly brings it off. With advances in filmmaking technology and possibly more money, Bed of the Dead has more polish and better gore effects than its inspiration. It also has a more elaborate narrative structure (characters caught up in the bed’s influence communicate across time, enabling one potential victim to escape). In parallel storylines, a cop investigates brutal deaths in a sex hotel while we see two couples intent on a bit of partner-swapping trapped by the malevolent furniture which is apparently determined to punish them for past sins – it was fashioned from wood from an ancient tree used for hanging murderers. I have to say I quite enjoyed it, and it turned out to be better than it had any right to be. Apart from a selection of unused music, the only extra is an interview with Barry about his disappointing experiences with the failed distribution of the original Death Bed. The Blu-ray is from Black Fawn Films, a Canadian company whose only previous release I was aware of is Jenn Wexler’s The Ranger.

Comments

The Monolith Monsters is one of my favorite movies too. I was happy to get the Blu-ray, it’s the 7th media version of the movie for me. VHS EP, VHS SP, VHS SP stereo, laserdisc, DVDR, DVD and Blu-ray. I’ve watched that movie a lot. I didn’t care for either commentary and wished they had some other extras.

I think it’s the fourth time for me – VHS, two separate DVDs, and now the Blu-ray. I haven’t listened to either commentary yet … I used to rip them and put them on my iPod classic to listen at work or while taking a walk, but the iPod finally died (after about ten years; the hard drive just spins noisily, quickly draining the battery) and I haven’t got around to replacing it with a new player.