Nuclear war and the movies

Since the end of World War Two, waves of anxiety about the Bomb have resulted in widespread political movements, paranoia and nihilism. As reflected in popular culture, it’s not surprising that such fears have often found incoherent expression. Before atomic energy was more clearly understood, it took on virtually magical powers as a storytelling device. In the 1950s, this most frequently involved human and animal mutations, providing a pseudo-scientific justification for boogeymen and monsters (most frequently by making things grow to enormous size to maximize destructive capability).

But along with these monsters, there was to a lesser degree a growing awareness of the more real dangers of the Bomb – that is, its potential for smashing the social and political framework which holds societies together. But even in these stories, there was a limit to the power of imagination to conceive of the scope of social collapse. In movies which tried to tackle the impact of nuclear war on contemporary society, there was a tendency to slip into the melodrama of personal conflicts. In Arch Oboler’s Five (1951), Ranald MacDougall’s The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) and Roger Corman’s Last Woman on Earth (1960), the central issue is that there are more men than women among the survivors, resulting in sexual jealousy and macho conflicts.

More ambitious attempts to depict people confronting their own inevitable destruction tended to be steeped in an air of fatalism, a feeling of helplessness in the face of forces beyond the individual’s power to affect events. These ranged from Ray Milland’s low budget Panic In Year Zero! (1962) to Stanley Kramer’s prestigious but ponderous On the Beach (1959). In the former, a family struggles to survive in a world of lawlessness and violence; but in the latter, it’s finally the real spectre of radioactive contamination and the horrific, lingering death it brings which hangs over a mostly stoic community who know they aren’t going to survive. It was this vision of inevitable death which fueled the anti-Bomb movements of the late ’50s and ’60s, a recognition that there was no option to “survive” a nuclear war and thus the only rational course was to abolish these weapons altogether.

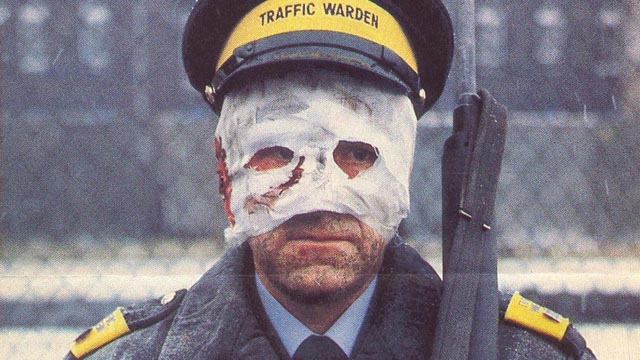

Not surprisingly, political and military interests saw these popular movements as a threat to their own power. In England, as protests grew larger and more intense, state reaction became increasingly oppressive and violent. It was in this atmosphere that a young filmmaker working at the BBC made the first truly realistic film about the immediate effects of a nuclear exchange on real people. Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1965), cast in the form of a dispassionate documentary depiction of an attack on southern England, is harsh and visceral and unrelenting. Its convincing recreation of the effects of the attack (visually drawing on images from Hiroshima and Nagasaki) were contrasted with quotes from actual political, scientific and religious authorities which seemed monstrous in their attempts to normalize the idea of nuclear war and play down the catastrophic effects of such an attack.

Watkins’ argument was so convincing that it terrified the powers-that-be at the BBC and the corporation refused to air the film. This suppression at home became an embarrassment when festival and theatrical screenings overseas garnered a number of prestigious awards – at the 1966 Venice Film Festival, the 1967 documentary festival in Bilbao, and finally the best documentary Oscar in 1967.

As the cold war dragged on into the 1970s, with international talks and agreements somewhat mitigating fear of the Bomb, pop culture more or less dropped the subject except for very tangential expressions in movies like Planet of the Apes (1968) and its sequels and things like Logan’s Run (1976), which were set in worlds long after the destruction had occurred. Towards the end of the decade, lower budget post-apocalyptic action movies emerged as a genre – the urtext for these movies was L.Q. Jones’ adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s A Boy and His Dog (1975), which established the arid desert wasteland as the setting of choice, although, unlike the movies that followed, Ellison’s story had a pointed satirical intent, mocking the right-wing ideal of a conservative middle-class middle America. It was George Miller’s Mad Max (1979) and more particularly its first sequel, The Road Warrior (1981), which cemented the genre’s conventions of small groups clinging to some semblance of civilization in the face of marauding tribes, with an heroic loner caught between the factions.

But with Reagan’s election and increasing tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., real-world fears of nuclear conflict reasserted themselves. In the U.S., this resulted in a pair of prominent productions. There was the TV “event” of The Day After (1983), written by Edward Hume and directed by Nicholas Meyer. This was an uneasy mix of multi-character TV (melo)drama with a visceral depiction of the effects of an attack on Lawrence, Kansas. There was a lot of controversy surrounding its airing, with anti-Bomb factions praising it for its likely impact on people’s attitude towards disarmament, while others (generally on the Right) condemned it for its defeatism and potential to undermine U.S. military strength in the face of an aggressive Soviet Union.

The Day After’s mix of documentary style and cliched dramatic elements does have some genuine impact, while Lynne Littman’s Testament (also 1983) erred on the side of tastefulness. A small-scale echo of On the Beach, this adaptation of a short story by Carol Amen which was published in Ms. Magazine depicts life in yet another small town after a nuclear exchange. Although the town itself was not directly targeted, the population knows that encroaching radiation is eventually going to kill everyone. As neighbours slowly succumb to the poison, a pall of fatalism hangs over one family which tries to live each day as it comes. Eschewing graphic depictions, the radiation poisoning seems more like those mystery diseases which have afflicted Hollywood stars since the silent era. This film, in trying to desensationalize and domesticate the horrors of nuclear war, inflected its fatalism with a paradoxical sense of human nobility. It provokes a comforting sadness rather than anger.

The biggest problem with Testament was its seeming reluctance to conceive of the total social breakdown which would result from nuclear war. Despite the horror, the painful sickness and death, it suggested that the community could remain mutually supportive in the midst of disaster; The Day After however ends bleakly with a small moment of futile connection between two figures ravaged by radiation waiting to die in the ruins.

Which brings us back to England, where once again the BBC financed the most realistic depiction of nuclear war and its social consequences seen in this period. Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984) owed a great deal to Peter Watkins’ The War Game in both tone and structure, but the script by Barry Hines (one of Ken Loach’s most important early collaborators, having written the feature Kes [1969] and the two-part BBC play The Price of Coal [1977]) combines the documentary elements with the story of a couple of ordinary families in Sheffield. This personal narrative centres on Ruth (Karen Meagher) and Jimmy (Reece Dinsdale), a young couple planning to get married, despite some opposition from her parents, because Ruth is pregnant. There’s a slight class element – Jimmy is not quite good enough for her parents – but the sheer ordinariness of their story is used as a deliberate counterpoint to the increasing international tensions which we hear about in background news broadcasts and occasional overt documentary insertions which inform us of the U.S. military presence in Britain which makes the country more vulnerable to attack.

Across the country, the ban-the-Bomb movement mounts demonstrations and the government begins to impose political restrictions in the name of maintaining “order”. As is inevitable in this genre, ordinary people are essentially powerless … but, as we see when local civilian authorities are mobilized to manage society in the face of impending war, organizing the police and food stores and so on, those ostensibly in charge are equally powerless. This is the larger problem of nuclear weapons, that their existence inevitably outstrips any ability of governments to control them and the consequences of their use. (Both The War Game and Threads highlight the pathetic lies governments peddle to their citizens about ways to protect themselves and survive an attack.) Once the attack occurs, everyone is on their own and essentially helpless. The special committee in their bunker almost immediately lose all communications with the outside and realize that they have no power … they succumb first to internal fighting among themselves and then eventually die in their hole from the effects of radiation.

Meanwhile above ground, those who did what they were told and tried to create protective shelters in their homes, slowly starve and grow sick, while outside those with enough strength confront intransigent authorities who refuse to release food from government stores, essentially telling survivors to return to their homes and “wait for order to be restored”. With civilians facing starvation, there are riots; police shoot looters. It’s obvious that there’s no possibility for a restoration of order, but no one knows what to do about the state of chaos.

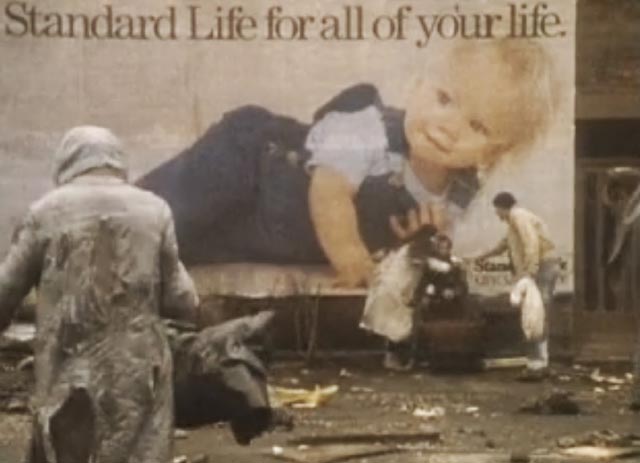

Where Threads goes further than The War Game and other films about nuclear war is in following the consequences for years into the future. Society is irrevocably smashed; nuclear winter makes the production of food impossible; language itself breaks down as the survivors are reduced to the most basic animal existence. Through this devastated world, having given birth to a daughter, Ruth wanders aimlessly, growing prematurely old. When she dies, her daughter carries on; there are no emotional connections now. Raped by other rovers, she in turn becomes pregnant and the film ends on a chilling image of her face the moment after giving birth, staring down at a baby we don’t see. Whether this child is physically damaged by radiation, malnutrition, disease isn’t shown; but the sheer hopelessness of its arrival in this world is devastating.

Made on a low budget, shot on 16mm with a relatively unknown cast, Threads has an air of realism far beyond its contemporaries. The production benefited from having access to an area of Sheffield which had been designated for destruction and rebuilding, allowing the filmmakers to tear down and burn entire streets to create a convincingly apocalyptic landscape of urban destruction. But although it stands above The Day After and Testament in terms of its creative achievement, like all films in this genre Threads provokes a sense of helplessness and despair in its audience. I don’t think this constitutes a failure of imagination; rather, it’s an expression of the simple fact that human politics is ultimately incapable of dealing coherently with this threat of our own making. The global political situation has changed since the height of the Cold War, but the existence of nuclear weapons remains a very real threat to our survival … particularly with the current instability of certain leaders who possess these weapons, who are less constrained by rational self-interest than earlier leaders.

With the revival of Threads on Blu-ray in an excellent edition from Severin Films, we have a timely reminder of the risks we face as Trump and Kim wave their big nuclear buttons at each other.

*

The Blu-ray uses a new 2K scan from what appears to be a 16mm print, with variable grain and visible dirt and scratches, although this slightly ragged look doesn’t undermine the presentation – rather, it adds a degree of authenticity to Jackson’s documentary approach to the material.

Extras include an excellent commentary from Jackson in conversation with writer Kier-la Janisse and Severin’s David Gregory; Jackson talks about the political and personal context which drove him to push for the project at the BBC, where he’d been making documentaries. The corporation’s willingness to back it was at least partly due to a sense of institutional guilt over the suppression of Watkins’ film twenty years earlier. Jackson provides a lot of detail about the improvisatory, guerrilla techniques which give the film its gritty realism, and goes into his stormy relationship with writer Hines.

In addition, there are interviews with actress Karen Meagher, director of photography Andrew Dunn and production designer Christopher Robilliard. And finally there’s an appreciative interview about the film with film historian and critic Stephen Thrower.

Comments

I’ve always liked the post-apoc type of film. I first heard of Five in a book about Frank Lloyd Wright, pre-VHS, and it was quite a few years before I got to see it. There sure seem to be a lot of new films in the genre. It’s so cheap to shoot some people wondering around in the desert. Hardly any of them seem to add anything new or interesting. Just beating the horse Max rode in on to death.

Best one I’ve seen in the past year or two is Turbo Kid. Very well made and a lot of fun.