The short career of Michael Reeves

British director Michael Reeves was only 25 when he died of a drug overdose in 1969. This fact has placed quite a burden on the work which he left behind – three low-budget features made in three years. For a long time fans in particular of his final film, Witchfinder General, lamented the loss of a genius who no doubt would have gone on to make a stellar career in the horror genre. While Reeves was undeniably talented and, in such a brief time at such a young age, did produce distinctive and interesting work, there is of course no way to know what he might eventually have done. But thanks to DVD, it is possible to examine what he did accomplish.

Producer Paul Maslansky gave him his first opportunity to direct with 1966’s The She Beast (La sorella di Satana), based on work Reeves had done for Maslansky on a Christopher Lee vehicle called Terror In the Crypt (1964). Recently released in a decent edition by Dark Sky, The She Beast is a clumsy mess marked by some impressive sequences and a lot of padding (much of it provided by an uncredited Charles B. Griffith doing extensive second unit chores) and attempts at satirical humour about the inadequacies of the Romanian communist state. But the opening sequence, with its execution of an 18th Century witch, in retrospect looks like a trial run for the full-blown horrors of Witchfinder General two years later.

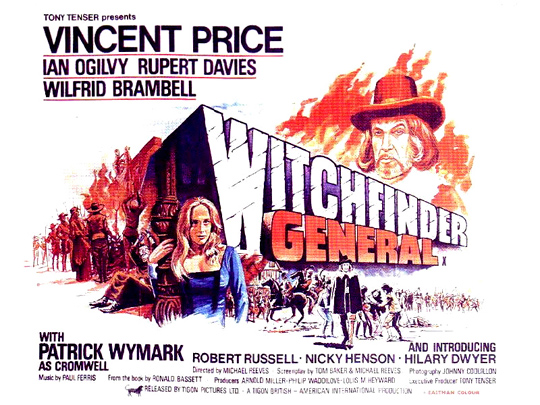

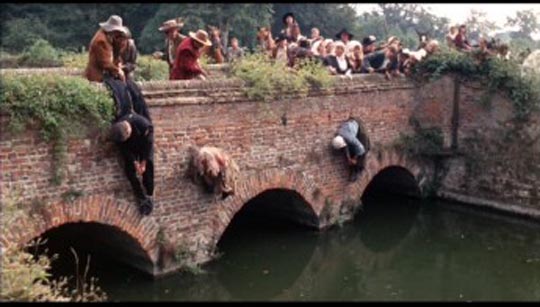

That film, very loosely based on the historical figure of Matthew Hopkins, follows the activities of a sadistic Puritan hypocrite who scours the English countryside during the Civil War in search of women to torture and kill in the name of God and State. For its time, Witchfinder General was a pretty bleak piece of work, eschewing a happy ending for a conclusion in which madness and violence consumes all the characters, even the young hero.

My own reaction to this movie has fluctuated over the years – I was initially bothered by the bloody ending in which Hopkins gets his brutal comeuppance, because it seemed to me that the historical truth was more chilling: I had read somewhere that Hopkins lived on into a ripe old age and died peacefully in his bed, having never paid for the terrible things he inflicted on innocent people. (Actually, although the details are not entirely clear, it appears that he died soon after the end of his witch-hunting activities, probably of tuberculosis, although there was a local legend that he himself was accused of witchcraft and executed – perhaps an early expression of the need for satisfactory closure on the part of the people he preyed on.)

But my response (apart from the issue of whether adherence to historical fact is actually all that important in a piece of storytelling) was based on an interpretation which saw Hopkins’ bloody death as an attempt to impose that satisfying sense of closure. Which, needless to say, was a very inaccurate interpretation. What actually occurs in the film is the devastating spread of madness to every corner of society, to the point where even good and decent people commit horrific acts. And in retrospect, this illuminates the character of Hopkins himself, perhaps a man initially driven by a sense of just cause who himself has been seduced by the pleasures of evil into committing acts worse than those of which he accuses his victims.

But although I now find Witchfinder General a more interesting and nuanced film than I once did, I still don’t find it entirely satisfying. It seems to be a transitional work, moving from the theatrical gaudiness of the Corman AIP Poe adaptations towards something more firmly based in reality. It shows the marks of having been made at the height of the Vietnam war, when atrocities and civil strife were on view daily on television screens. But it starred Vincent Price, the wonderfully hammy heart of those Poe films. I’m a big fan of Price’s work, his rich theatricality, and in his later years his great sense of humour about his own image. But when I watch Witchfinder General, he seems to get in the way, pulling the film back from where it’s trying hard to go. (A year ago, BBC Radio 4 broadcast an amusing play by Matthew Broughton called Vincent Price & the Horror of the English Blood Beast, which gave an account of the young Reeves’ struggle to overcome Price’s persona and obtain a performance more appropriate to what he was trying to do. Although no longer available from the BBC’s own website, it can probably still be found as a torrent.) As a matter of personal taste, I actually prefer Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil (1970) as a depiction of the sexual pathology of witch-hunting (and I prefer Herbert Lom’s sadist to Price’s) and Piers Haggard’s Blood On Satan’s Claw (1971) for the opposing viewpoint that witchcraft and Satanism were actually real.

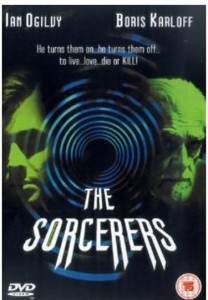

Of Reeves’ three films, the one I personally like best is the second, The Sorcerers (1967, a now out-of-print region 2 DVD, still available from some sellers on Amazon UK). Although made on a very low budget, it escapes the kind of compromises that undermined The She Beast, and as a contemporary story avoids the conventions and paradoxical comforts afforded by the period setting of Witchfinder General. It also gave Boris Karloff one of his finest late-career roles as the scientist-inventor Marcus Monserrat who has come up with a device which allows someone to link his mind with that of another person. This device is like a precursor to the experiential recordings at the heart of Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995), although Monserrat’s machine permits the real-time sharing of experience.

Monserrat lives with his ageing, embittered wife (the superbly creepy Catherine Lacey) who sees his invention as a way to escape from the crippling decline of her own body. When Monserrat persuades a bored young man (Ian Ogilvy, star of all three of Reeves’ films) to submit to the machine, she quickly becomes addicted to living vicariously through him. And rather than remaining a mere passive observer, she discovers that she can take him over and control him. Freed from any normal moral constraints, she propels the young man into increasingly dangerous, even criminal activities, as her loving husband looks on in horror at the effects of this addiction on her personality.

There are many things going on in this little movie – bitterness and resentment at growing old, envy of the young and anger at the thought that they are wasting what the old woman no longer possesses; acting out of stereotyped projections about who the hedonistic younger generation are; the deformation and destruction of personality by addiction; the loss of identity and control to technology. As Phil Hardy points out in The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Horror (The Overlook Press: New York, 1995), the critique of cinematic voyeurism in Reeves’ film bears comparison with Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. And it all occurs in grubby London locations, centred on a cramped row house where the old scientist sees his dream turning into a nightmare.

Although Witchfinder General is undeniably a more polished and technically accomplished movie, it’s The Sorcerers which makes me feel that Michael Reeves might well have gone on to create an interesting and innovative body of work. Or rather, I wish he had had an opportunity to make more films like The Sorcerers, rather than bigger and better Witchfinder Generals. But who knows what his own interests and the pressures of the troubled British film industry would eventually have enabled him to produce?

Comments