Ghosts Good and Bad

Whether or not ghosts really exist – and just what they are if they do – in art and literature (and film), they serve several well-defined purposes. For instance, the spirits of the dead may linger on in order to resolve some unfinished business – making sure a grieving loved one comes to terms and manages to get on with his or her life; helping to ensure the exposure of their own murderer or the location of an important document or valuable inheritance. On the negative side, they may stick around in order to get revenge, to punish the living for their crimes. Or they may serve a more oblique purpose as manifestations of someone’s suppressed emotions or psychological problems.

Kill, Baby … Kill! (Mario Bava, 1966)

The latter two points are blended effectively in one of Mario Bava’s masterpieces, the unfortunately titled Kill, Baby … Kill! (1966; in Italian Operazione Paura, literally Operation Fear), which is one of the finest Gothic ghost stories ever put on film. Something is driving the inhabitants of a small Carpathian village to kill themselves and a doctor, Paul Eswai (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart), arrives to investigate the deaths. He finds the population living in fear and during an autopsy discovers that a coin has been inserted into the heart of the latest fatality. Local superstition says that this will prevent the dead from coming back to plague the living.

The menace turns out to be a young girl dressed in virginal white, playing with a ball which unnervingly bounces into scenes as a signal that something bad is about to happen. (This figure has famously inspired numerous other filmmakers, including Fellini in Toby Dammit, his episode of the omnibus Spirits of the Dead [1968], William Malone in feardotcom [2002], even Martin Scorsese in The Last Temptation of Christ [1988], in which the Devil appears to Christ as a young girl.) This ghost child is Melissa Graps (played creepily by a boy, Valerio Valeri), the daughter of the local Baroness (Giovanna Galletti), who died years ago after being run down by the horses of drunken villagers during a local festival.

The motive is obviously revenge, but it’s narratively complicated; whether Melissa is an actual ghost bent on revenge or rather a manifestation of the Baroness’ anger and hatred remains open; what is not in question is the supernatural force which permeates the entire village and to which the victims submit with fearful resignation because they all accept the fact of their collective guilt.

This great film has finally received a worthy presentation on Blu-ray – from Kino Classics in the U.S. and Arrow in England. I have the Arrow dual-format edition, which has more substantial supplements than the Kino (and according to DVDBeaver is technically superior). Interviews with co-star Erika Blanc, assistant director Lamberto Bava, and critic Kat Ellinger provide some interesting context and, as always, the commentary from Bava expert Tim Lucas is packed with production details and critical insight. Semih Tareen’s short homage to Bava and the giallo, Yellow (2006), is also included, along with an alternate German title sequence, a trailer, and a booklet essay by festival programmer Travis Crawford.

*

A Ghost Story (David Lowery, 2017)

David Lowery’s A Ghost Story (2017) is something completely different. Friends had recommended it to me and I’d glanced at (but not read through) a few reviews which offered decidedly mixed opinions. My impression was that the film had been built around a risky conceit – the ghost is literally someone covered by a bedsheet with a couple of eye holes. It would obviously take a lot of skill to bring this off – and some reviewers simply found it ridiculous and laughable.

What surprised me most, though, was not that the bedsheet works, but that the film doesn’t follow the trajectory I had expected. I assumed that this was one of those familiar “ghost helps loved one move on with life” stories (like Jerry Zucker’s Ghost [1990]). And it does seem to start off that way. Musician C (Casey Affleck) lives with M (Rooney Mara) in an ordinary ranch house on a nondescript semi-rural road. In a quick series of scenes – shot tableau-style in a ratio of 1.33:1 – we see their life together, seemingly warm and affectionate, but with hints of some kind of tension revolving around his immersion in his work and her desire to move on to something more. When they are woken at night by strange noises, an atmosphere of unspecified unease seeps in.

Whatever the tensions in their marriage are, they are left unresolved when C suddenly dies in a car crash. After M visits the morgue to see him one last time and gently pulls the sheet back over his face, the camera holds on the shot for a very long time. We hear various offscreen noises – footsteps, the squeaky wheels of a gurney – and then the body abruptly twitches beneath the sheet. This moment of pantomime sets the tone for what follows; through physical movement alone, Affleck conveys confusion and then curiosity and gradually increasing determination. Somehow, what could so easily be ludicrous, stirring memories of Caspar the Friendly Ghost, is infused with an air of deep melancholy.

The ghost wanders through the hospital and finds itself confronted with a portal through which a bright white light pours; it pauses, makes a choice not to pass through, and the portal closes. The ghost leaves the hospital and walks through an empty green landscape at dawn, slowly making its way back to that ranch house, where it bears silent witness to M’s grief. But it remains an observer, unable to influence or comfort her. This is where the film takes off on an unexpected trajectory.

As a passive observer, the ghost witnesses a progression of new tenants in the house after M moves away (having slipped a tiny note into a crack in a doorframe). The first of these interlopers is a Hispanic mother and her two children. The ghost haunts the children, then in a moment of rage turns poltergeist, smashing everything in the kitchen in front of the family, driving them out. Then there’s a crowded party, with people mentioning the house’s reputation for a haunting. A man launches into a lengthy monologue about the contradiction between a human desire to create and leave something of lasting value and a universe which is destined to end and erase everything.

The ghost, on a micro scale, bears witness to this entropic process; the house falls into disrepair, is demolished, huge buildings erected in its place which eventually become a vast city. When the ghost finally commits a kind of suicide by falling from a high building, it finds itself in an empty landscape which turns out to be the site of the ranch house in the past as the first settlers arrive. Seemingly caught in a loop, trapped in the same location in space but circling in time, the ghost finally arrives back at the point where the film began, now observing C’s relationship with M from the outside, in the context of that cosmic perspective; able now to acknowledge the flaws in the relationship, perhaps feeling regret, the ghost turns out to be the source of the sounds which disturb C and M in the night.

Alone again in the house, the ghost retrieves the note left by M and is finally released.

In taking the untethered perspective of the ghost, A Ghost Story is unlike any other film I can recall. It begins in a small personal space and travels inexorably into something vast and impersonal, with years, perhaps even centuries, passing in a moment. (In this, although very different in its details, it is reminiscent of the “cosmic horrors” of H.P. Lovecraft and others, particularly William Hope Hodgson, who found both fear and awe in the difference between human experience and the inhuman scale of the universe.) The sheeted figure is strangely expressive in its stillness and silence (echoing No-Face in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away [2001]); rather than being laughable, it is – well – haunting. As the film moves increasingly far from the personal space of the opening scenes, it grows more deeply moving and, paradoxically, as individual human life shrinks in relation to the vastness of time and space, it becomes more precious. That all of this can be conveyed mostly through stillness and silence is remarkable.

*

Zeder (Pupi Avati, 1983)

Ghosts are spirits which have survived the physical death of the body. Zombies – at least, post-Romero zombies – are the polar opposite: bodies which have survived the death of the spirit. (More traditional zombies are typically bodies in which the spirit has been suppressed by a more powerful controlling external will.) This is why zombies are generally more terrifying than ghosts; the latter hold out the idea of the survival of some kind of consciousness, while the former suggest the complete obliteration of individual identity.

Although there seems less room for variant forms of zombie narrative – everything from Night of the Living Dead to 28 Days Later to World War Z centres on the relentless drive of death to wipe out the living, or rather to consume the living – subtle variations are possible. I recently re-watched one of my favourites, a film which genre fans seem to hold in generally low regard specifically because it avoids gut-munching, rampaging hordes. Pupi Avati’s Zeder (1982) begins as a mystery but gradually slips into horror as the protagonist, a writer named Stefano (Gabriele Lavia), investigates the work of a missing scientist named Paolo Zeder.

In an odd case of creative coincidence, the underlying ideas of Avati’s film closely resemble Stephen King’s novel Pet Sematary, which was published around the time the film was released. Zeder proposed that there are places on Earth called K-Zones, nodes in space-time where the border between life and death ceases to exist. Stefano’s investigation leads him to a group of scientists conducting experiments in one such area in an attempt to revive the dead. As in King’s novel, what is revived is not the original person, but rather that person’s body animated by some malevolent force.

Zeder burns with a slow fuse, building tension gradually but relentlessly as a vision of cosmic dread opens up before Stefano; its tone and method is quite Lovecraftian and, although towards the end there are overt moments of horror, its main thrust is towards a claustrophobic sense of human fragility in the face of a cold, insensitive universe.

Zeder is one of those movies I’ve bought multiple times over the years. The first time I saw it was on the Image Euroshock Collection DVD from 1999. The pan-and-scanned image was pretty awful and it only had the English-dubbed soundtrack. An Italian 20th Century Fox DVD from 2002 was a great improvement, with a bright widescreen image and both Italian and English soundtracks. (The documentary extra unfortunately was only in Italian with no subtitles.) But the new Code Red Blu-ray renders previous editions totally redundant … well, almost.

Although the image quality is excellent, the disk has one huge flaw. Code Red have taken the lazy route and provide only subtitles for the hard-of-hearing synced to the English dub. They haven’t actually translated the original Italian track. Which means that not only are there distracting music cue and sound effect subs, but there are also numerous occasions when there are subtitles where there’s no Italian dialogue and others where there’s dialogue with no subtitles. So it’s impossible to know what’s actually being said in the Italian track (even when sound and subtitle do coincide, it’s occasionally obvious that the text has nothing to do with what’s being said). Known as “dubtitles”, this practice has plagued DVD and Blu-ray for years, displaying distributors’ contempt for their customers. In order to avoid irritation, it means you have to watch the English dub, which is distracting for its own reasons.

The disk has a half-hour interview with director Avati (and a six-minute clip with star Lavia) and considering how bad the subtitles are here, it may be best that they didn’t make an effort on the feature itself. The two and three line paragraphs in a tiny font are virtually unreadable – the best you can do is quickly scan for the gist. Given that subtitles have been around since the movies first started talking, it shouldn’t be difficult to get this right and I can only assume Code Red just wasn’t willing to spend a little extra cash to do this properly … which is really unfortunate given the quality of the release in every other respect.

*

Recent reading

Speaking of Mario Bava, I recently finished reading Tim Lucas’ daunting Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, at 1200-odd pages (with four columns of text), surely the largest book ever written about a single director. Lucas’ decades of research and writing produced a tribute to a filmmaker who, while hugely influential, might have remained a minor niche figure for most viewers. In detailed accounts of Bava’s work as a cinematographer and visual effects technician, Lucas situates him at the heart of Italian film for forty years (1939-79). It was from the point-of-view of that cameraman and technician that Bava approached his own directing career, working mostly with very small budgets (and often problematic and inadequate scripts), hand-crafting his features to create emotions and themes through almost purely visual means.

I’ve been a Bava fan since I first saw Kill, Baby … Kill! on late night TV in the mid-’70s. That was out in Neepawa, where our rooftop antenna pulled in a weak signal from Winnipeg 110 miles away. I saw the film through a haze of video snow, a ghostly image reminiscent of Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932) which seemed to evoke a memory of some dream I’d long-since forgotten. In some ways, that remains my most satisfying experience of the film. Seeing it now in all its pristine glory on Blu-ray, while it has its own beauty, the clarity of the images lacks that added degree of mystery I experienced back then.

Lucas’ book has added to my appreciation of Bava’s work, with his critical evaluations finding layers of meaning which had not always been apparent to me. Particularly useful are his close comparisons of the various versions of many of the films and the ways in which alternate cuts (by American-International, for instance) sometimes completely alter the meaning and aesthetic effects of the Italian originals. The one point at which I felt confident enough to depart from Lucas’ opinion was in regard to Rabid Dogs. Although left uncompleted by Bava when the funding fell through, it was first “finished” by lead actress Lea Lander and Peter Blumenstock of Lucertola Media (which made it the world’s first DVD-only release in 1998). This release, despite technical flaws, revealed the film to be a remarkable departure for Bava, one which if completed in the year of production may well have revitalized his career. But controversy greeted the Lander/Blumenstock version, which was essentially Bava’s rough cut with a new title sequence added.

Bava’s son Lamberto complained that this didn’t represent his father’s intentions, that certain elements had not been filmed at the time the production was shut down. Lucas and others have commented that, as a rough cut, the film is unfinished in other ways – that Bava would have tightened the editing and refined the pace. This is no doubt true, but even as it stands Rabid Dogs is a remarkably gripping and intense experience. And, to my mind, it’s far preferable to what Lamberto and Bava’s one-time producer Alfredo Leone did to the film (in something like the fifth variation to be created from the original footage!), released as Kidnapped in 2001.

The rationale was a) that everything had to be tightened up considerably and b) that elements in the original script should be shot and edited in. Whether Bava himself would eventually have incorporated those elements is far from clear – and given the detrimental effect of including them, it’s quite possible he would have eliminated them himself. Those elements consist almost entirely of scenes and inserts which drag us away from the core characters trapped together in a small car trying to escape the police after a robbery. We get generic shots of a police communications centre which give us no information we don’t already have, generic shots of police cars and helicopters out looking for the robbers, and new shots of a woman awaiting communication from whoever has kidnapped her son. These last completely undermine the film’s shocking ending, while all the police activity merely disrupts what would otherwise be (as it is in the Lucertola version) one of the most intense and claustrophobic thrillers of the then-burgeoning poliziotteschi genre.

Lucas is more critical of the Rabid Dogs version than I am, and far more tolerant of the Kidnapped cut than I could ever be. Given the absence of a final Mario Bava version, I’ll take the one which provides the most intense and involving viewing experience rather than the one which claims to reflect the intentions of the original script. As anyone who has worked in film knows, scripts are guides, not Bibles to be slavishly adhered to. In the end what matters is what works – Rabid Dogs works, but Kidnapped really doesn’t.

*

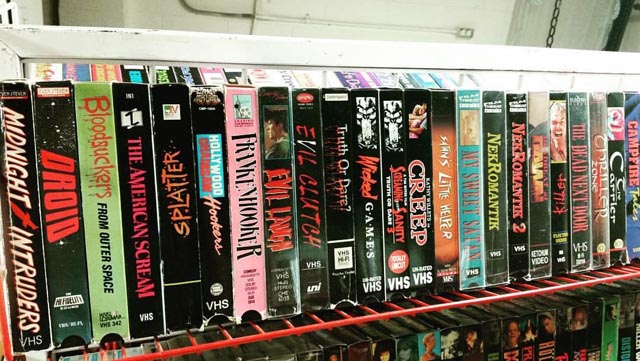

And speaking of Tim Lucas, I’ve been browsing through The Video Watchdog Book. First published in 1992, it’s a collection of all the columns he wrote for various magazines before launching the late, lamented Video Watchdog magazine itself in 1990. Although obviously outdated – home video was only just taking root during the time covered, 1985 to 1992 – it’s quite fascinating to see how rocky the birth pangs were. Hard to remember even what it was like watching pan-and-scanned VHS tapes, often with no assurance that you were seeing the complete movie. Hard also to believe that in the early years, a collector might pay $60 to $80 for one of those tapes. The landscape has changed so radically in the subsequent three decades that Lucas might have been writing these columns in the Dark Ages! But he played a key part through these columns and the subsequent magazine in creating an environment in which producers and distributors began to take the medium seriously, and those of us who now obsessively collect DVDs and Blu-rays are the direct beneficiaries of his pioneering efforts to treat film history with respect in these evolving formats.

Comments