Hometown Talent

My friend Dave Barber, programmer of the Cinematheque here in Winnipeg, has spent the past couple of years working with filmmaker Kevin Nikkel to put together a feature-length documentary about the history of the Winnipeg Film Group. I went to a screening recently, courtesy of a ticket provided by Dave, and came away with mixed feelings. The film – Tales from the Winnipeg Film Group – features a lot of interviews (which is only natural given that the subject spans four decades) and is heavily loaded with clips from dozens of films made by members over the years. But in a way, that wealth of material ends up being a potential drawback: the subject is so big, so diffuse, that it could probably never be contained in a single documentary.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the doc is tightest and most coherent in the first half as it sketches in the origins of the Film Group in the mid-’70s as part of a national movement to generate a home-grown film culture. Several of the people involved in its formation were interviewed (critic Len Klady, producer Merit Jensen, editor Bob Lower, film academic Gene Walz, filmmaker Allan Kroeker) and the early chaotic attempts to find a structure and filmmaking practice within a co-op environment are sketched in quickly and vividly. In those early days, there was a somewhat lefty and doc-centric ethos among the founding members, but the collective also attempted to become a producer of dramas. This didn’t go well, with a short comedy named The Washing Machine turning into a money-devouring debacle.

The members soon realized that it would be better for the Group to be a facilitator rather than an active producer; it became a place where individual filmmakers could access production equipment, find sources of funding, and work together to help each other realize projects. There was a club-like atmosphere when it was located in a house on Adelaide Street, but things began to slip when the organization moved into new premises in the Artspace Building in Old Market Square; this six-story edifice, built in 1900 to house a wholesale business, was re-conceived as a central location for numerous arts groups which would be able to cross-pollinate and support each other. The move also transformed the Group’s original informality into something more structured … and in the ensuing three decades the struggle between bureaucratic control and unfettered artistic liberty was played out by a string of administrators, boards and shifting membership.

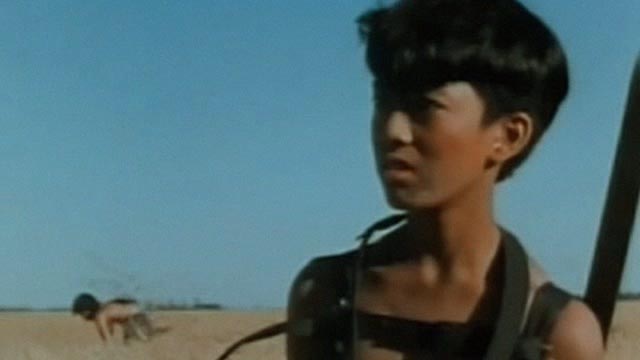

It was in the ’80s that the biggest shift occurred. Many of the original founding members had moved on to work in a growing local industry – the arrival of a National Film Board office provided a more stable base and better funding opportunities for those interested in documentary – while the two most prominent filmmaking members of the decade took a radical turn not only into drama, but into a distinctively non-commercial form of imaginative filmmaking. First John Paizs launched a series of short, deadpan comedies which played with various forms – most successfully in Springtime in Greenland (1981), which uses the seemingly artless techniques of industrial/promotional films to create a devastatingly funny satire on the psychological and emotional bankruptcy of suburban life.

From 1980 to ’85, Paizs produced a series of imaginative, self-referential (“post-modernist”) comedies, culminating in the feature Crime Wave (1985), which despite impressing audience and critics at the Toronto Film Festival, failed to secure any kind of broad distribution. Paizs subsequently disappeared into television, but his influence inspired Guy Maddin, who has had the most successful and sustained career of anyone who started out at the WFG.

Although all this happened three decades ago, the shadows of Paizs and Maddin stretch over the whole subsequent history of the Film Group. They established the image of Winnipeg’s “Prairie Gothic”, a cinematic world rooted more in some kind of deranged inner universe than the physical landscape of the Prairies. The reasons for this have long been speculated about as if there must be some strange environmental explanation for what makes Winnipeg filmmaking different from, say, Toronto or Vancouver filmmaking. Nothing fruitful has ever come out of this kind of speculation, partly because it tends to ignore the specific individual interests and experiences of the filmmakers in question (for instance, Maddin’s interest in the work of writers like Robert Walser and the aesthetics of silent film). Dave and Kevin’s doc raises the old question, mocking in passing a famous CBC television magazine piece which rather desperately searched for a single specific explanation – exasperated interviewees on that program eventually attributed it to lead in the water.

But the doc itself has no answer and falls into the cliche that it has something to do with “Winnipeg’s isolation from the centre” (i.e. Toronto). While it’s true that cities distant from the mainstream do perhaps produce artists who aren’t defined or compromised by the commercial pressures of well-established industries, that alone doesn’t explain our particular distinctiveness (any more than Shirley Jackson’s life in smalltown Vermont “explains” her acutely disturbing fiction, or David Lynch’s idyllic childhood “explains” his intense cinematic nightmares). In raising the question, but then falling back on familiar tropes, the doc expends energy perhaps best used elsewhere.

It’s here around the halfway point that Tales from the Winnipeg Film Group begins to lose focus and in the second half it tries to rein in multiple disparate themes, becoming a series of brief chapters on various topics. The ’90s are marked by a number of “transgressive” filmmakers – Jeff Erbach, Gord Wilding, Noam Gonick – and the commercial and practical failure of a number of filmmakers to launch sustained feature careers. There’s a lengthy section on the Group’s image as a “white boys’ club” which presented barriers to women and non-white filmmakers. It sketches in briefly the late ’90s, early ’00s flowering of a more aggressively experimental approach as Sol Nagler inspired a number of filmmakers to hand-print their films. There are glimpses of the political fights which have always been a part of the organization, although again Dave and Kevin don’t (can’t?) go into too much detail. For those of us who know a lot of these stories (and lived through some of the storms), the doc seems a bit coy here, although it is understandable that they can’t say too much because there are no doubt legal ramifications in naming names.

Towards the end, the doc puts emphasis on the increasing presence of indigenous filmmakers and women, suggesting that there has been some evolutionary process, yet no one emerges to challenge the stature the film has given to Paizs and Maddin … but perhaps that’s as much a reflection of a radically changed media landscape as it is of individuals’ creative potential.

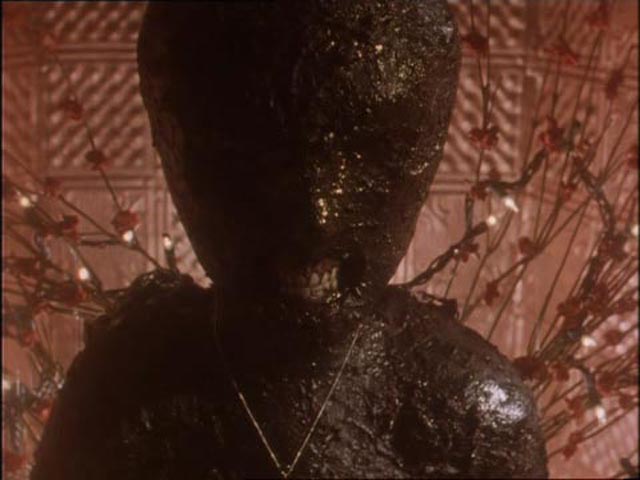

If I’ve been leaning hard on the doc’s faults, that’s really only because what has been left out is so obvious to someone who, at least for a while, lived within the WFG bubble (I worked there for three-and-a-half years in the early ’90s, made three short films of my own with their financial and technical aid, and edited a number of others for various members). Having subsequently made documentaries of my own, I’m only too aware of the pain involved in leaving much of your material on the cutting room floor. Dave and Kevin got some good interviews and throughout the film there are lively and engaging anecdotes which give vivid glimpses of what it was like to be a part of it all – like Shereen Jerrett’s story of her dog gnawing at the WFG studio floor trying to get at the blood which had seeped into the wood during the shooting of the final scene in Jeff Erbach’s Soft Like Me, which involved me and Rick Fisher up to our elbows in stinking slaughterhouse offal.

Tales from the Winnipeg Film Group is a polished and entertaining documentary which in the end provides engaging glimpses from a long and complicated history which can’t be fully contained within a single feature.

Comments