Guest post:

A Weimar Cinema Revelation: Harbour Drift (1929), part one

My friend Howard Curle had the enviable experience of catching a couple of screenings at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival at the beginning of June: a Swedish comedy from 1926 called The Girl in Tails, directed by Karin Swanstrom (who was credited with discovering Ingrid Bergman), and a late Weimar silent by a previously unknown (to me and Howard, at least) director named Leo Mittler. Here, in the first of three guest posts about the film and the filmmaker, Howard writes about Harbour Drift (1929).

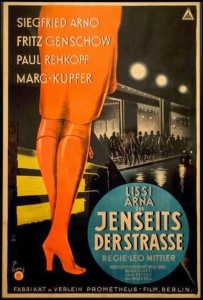

The German silent film Jenseits der Strasse/Harbour Drift (1929) begins with the camera zigzagging along a bustling Hamburg sidewalk before stopping to observe an obese gentleman seated at an outdoor café. As he reads a broadsheet spread between his raised arms, a crime story is outlined via intertitles: the corpse of an old man has been fished out of the harbour, its condition suggesting he’d been involved in a terrible struggle. Then slyly, the man lifts the paper and shifts his gaze to the legs of a woman seated at the next table whose leather boots are laced half way up her calf.

Even as I was caught by the disturbance of this opening sequence – rather like seeing a George Grosz sketch come to life in shades of slate grey – I was also trying to determine, having never heard of its director, one Leo Mittler, where this movie was coming from stylistically. If the initial track down the sidewalk suggests a Murnau-like influence from The Last Laugh, then the café episode takes on the look of early Hitchcock, with multiple shots analyzing the man’s voyeurism. However, a more agitated montage of a particularly Soviet type would soon assert itself as the film’s dominant discourse, while the vivid expression of the actors would also claim my attention. Harbour Drift, made by the relatively small production company Prometheus, turns out to be not unlike a number of other late-’20s movies where you sense that the filmmaker, desperately aware of the sound revolution already arrived, is trying to pack as much expression as possible into an art form whose dominion is over. As Paul Schrader has said, 1929 was the year silent films “broke boundaries trying to fight off sound.”

My speculation about influences is enhanced, I’ll admit, by the ideal circumstances under which I experienced the film. The San Francisco Silent Film Festival has done much to cultivate the appreciation of pre-sound era cinema. Now in its 19th year with screenings at the Castro, a handsome single-auditorium house, the festival attracts generous sponsors and enthusiastic crowds. Patrons appreciate not only excellent prints and (I imagine) DCP renderings, but the well-organized management of crowds, a measure of which is the even temper of people snaking down the lower-level staircase or filing into a corner of the lobby to use the washrooms. Boisterous applause greeted the performance of live music at the screenings. In the case of Harbour Drift, the musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius added significantly to the psychological dynamic and atmosphere of the story.

Back to the movie: a covetous gaze again governs the film’s second sequence. On the same sidewalk in front of a busy store catering to middle-class shoppers sits a old beggar (Paul Rehkopf), his music box before him. Prior to entering the store, a woman fiddles with the contents of her purse, carelessly dropping a pearl necklace. No sooner does the beggar spy the object than he snaps it up but not so quickly that the incident can escape the gaze of another woman (Lissy Arna). The beggar vacates his place and the woman follows him home – a decrepit houseboat in the harbour which he shares with a young unemployed dockworker (Fritz Genschow). Cheered by his good fortune, the beggar invites the younger man to join him at a subterranean tavern, the Electric Bar, where we encounter the young woman again, this time in the company of a fence (Siegfried Arno) and his muscle (Friedrich Gnass).

Amid a fog of cigarette smoke, the two young men exchange leering, suspicious glances and soon a brawl erupts between them for the attention of the woman. The beggar deserts the place and the woman takes the winner of the fight, the young dockworker, home. Briefly they achieve an intimacy that both mistakenly think can unite them. But when the landlady demands not only rent money but also extra for services rendered, the illusion of the woman’s status is shattered: the landlady is exposed as her madam, the fence as her pimp. Urged by the woman to steal the necklace, the youth betrays his pact with the elderly beggar. The inevitable confrontation proves a disaster for all concerned. The jobless young man disappears into the fog which surrounded him in his first appearance loitering about the harbour; in a clever conceit, the prostitute turns out to be the woman in the calf-length leather boots and the corpse retrieved from the harbour in the newspaper story is that of the beggar. The film ends with the prostitute joining the gentleman, his obese body blocking out her figure as they walk arm in arm through the throng on the sidewalk.

As this outline suggests, Harbour Drift is determinedly bleak, only hinting at alternative possibilities, interestingly, not of working-class solidarity, but rather of sentimental connection between male and female. These include not only the morning interlude between the prostitute and the dockworker but also earlier in exchanged glances and smiles between him and a harbour waif as he shaves and she starts work. Bleak, yes, but aside from one extended montage reiterating the unemployed youth’s inner struggle before confronting the beggar, always compelling. Cinematographer Friedl Behn-Grund alternates high and low angle shots that establish space then dissemble it; the film exposes and dissects faces, gestures, objects, until only a human desperation remains.

For its representation of late Weimar society alone, Harbour Drift is a valuable social document, amalgamating as it does elements of German Expressionism, Soviet montage and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the third a blunt, unflinching style especially evident in the sidewalk and café sequences which bookend the film. The craftsmanship of the filmmaking and the vibrancy of the performances strike me as self-evident. Why then has this film been so lacking in appreciation? Could it be that because the film did not make a big impression critically or commercially at the time of its initial release and was made by a director whose subsequent films were quite mediocre, it is thought to be undeserving of attention? Does Leo Mittler deserve a better reputation, perhaps more analogous to Paul Fejos’s in regard to the recently revived Lonesome?

I want to try to get a handle on these questions in the second installment of this essay. To begin, just who is Leo Mittler? Meanwhile, if any readers were able to see revival screenings of Harbour Drift or are familiar with a version of the film under its other English release title, Beyond the Street, I welcome comments.

– Howard Curle

Comments

I absolutely adore the film Harbour Drift (1929). To me, it is one of THE greatest Avant-garde films ever made. Some of the most gorgeous pieces of camera work, cutting, and pacing, along with a story of dark underground intrigue. It boggles the mind that Jenseits der Strasse/Harbour Drift (1929) isn’t more well known and hasn’t seen any kind of commerical DVD or Blu-ray release. This would be a perfect film for BFI, Eureka! Entertainment, Criterion Collection, or Kino Lorber to bring out from obscurity. The film has all the trappings for a successful resurrection.

Your comment is very timely. My friend Howard, who wrote this piece, died in August and at his memorial on Sunday, two days ago, I mentioned his efforts to research Harbour Drift and its director Leo Mittler. If he were still here, he would have been thrilled to discover another admirer and eager to discuss the film with you.