A mixed bag from Screen Archives

One of the pleasures of being a compulsive collector is the occasional discovery of something which was previously completely unknown. In some ways, this is even more satisfying than finally obtaining something I’ve heard or read about for a long time, but never before had a chance to see … or something seen long ago which I haven’t until now had an opportunity to revisit for years. In the latter category are things like the one-season-only James Garner TV series Nichols (created by Frank R. Pierson), which lasted twenty-four episodes in the 1971-72 season. It was never repeated as far as I know, and I don’t think it got a home video release on VHS. But after recently watching John Sturges’s Hour of the Gun, I was poking around on-line and discovered that the series had been released on DVD by Warner Archive in 2013. So I had to order a copy. Now, that’s a forty-six year gap, so I was a bit nervous that it wouldn’t live up to my memory … but right from the first moments of the first episode all that intervening time just seemed to slip away. The show feels totally fresh and undated. The writing, direction and, particularly, the cast are all excellent.

In the second category are things like Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight, which I first read about probably back in the ’80s, and only finally got a chance to see ten or so years ago when I managed to acquire a Spanish DVD. The disk quality wasn’t very good, but it had been worth the wait. I went through one more DVD edition and the first (disappointing) Blu-ray release from Mr. Bongo in England before finally seeing the film in all its pristine glory on Criterion’s Blu-ray last year.

And in the first category – things previously unknown and unheard of, like Paul Fejos Lonesome (1928) and Anthony Asquith’s Underground and Shooting Stars (both also 1928) – are a great disk I just bought on spec in a sale on the Screen Archives website. I knew nothing about it, but it sounded interesting and was really cheap, so I added it to an order for Blu-rays of Stephanie Rothman’s Terminal Island (which I knew of but had never seen) and a Cinerama curiosity called Holiday in Spain.

*

Derby (Robert Kaylor, 1971)

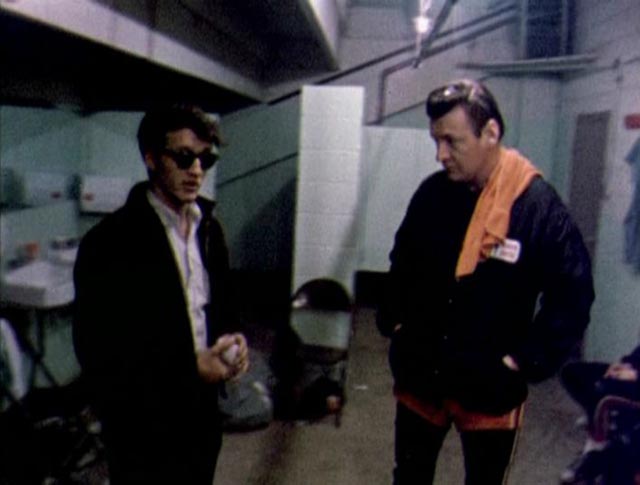

The DVD in question is Derby (1971), a documentary feature made by Robert Kaylor (who I previously knew nothing about), and produced by William Richert (who directed the wonderfully demented, underrated paranoid thriller Winter Kills [1979]). Kaylor and Richert had set out to make a documentary about roller derby and were following a particular team led by Charley O’Connell when in walked a young man named Mike Snell. Mike – who worked in a tire factory in Dayton, Ohio, and was married, with a young child – had decided he wanted to be a roller derby star and he wanders into the dressing room and asks O’Connell for advice. Apparently there’s a training place in California where wannabes can learn the essentials during a six-week boot camp. Mike figures he can do it all in three weeks and plans to head West.

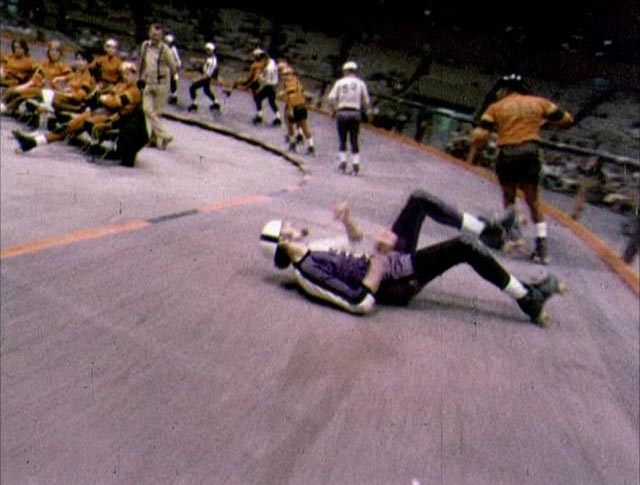

The film cuts between action in the rink – fast, bone-crunching and fueled by inter-team anger, it looks very much like Rollerball minus the steel cannonballs – and Mike’s daily life. Kaylor adds no narration, relying on often startlingly revealing verite scenes between Mike and his wife, his brother and friends. (There are some more direct interviews with O’Connell which hint at what the film might have looked like before Mike showed up and drew the filmmakers’ attention.) Some of this is funny, some of it quite uncomfortable. The editing of many scenes raises a suspicion that we’re watching staged moments (an issue addressed in no less than two commentary tracks, one with Kaylor, the other with Richert).

Derby has a raw energy; it was shot on 16mm, with, according to Kaylor, a shooting ratio of only 1.5 to 1, which means that we get to see pretty much everything that was shot. This explains a certain raggedness of construction. There’s a visceral power to the roller derby sequences, portions of which were actually shot by the participants carrying small, compact cameras during the games; the editing is fast-paced, emphasizing the seemingly brutal physicality, while never actually making clear what the point of the “sport” is beyond trying to disable the opposing team.

The sequences of Mike’s home and work life, on the other hand, are allowed to breathe, which gives rise to a certain voyeuristic queasiness. He, his wife and friends and relatives live a tough, low-paying working class existence and even though Kaylor maintains a degree of objective distance, for the viewer there’s an inevitable feeling of poverty tourism. The very unguardedness of these people (there’s a remarkable scene in which Mike’s wife Christina walks down the street with a friend to confront a woman who’s been having an affair with him, and they have a lengthy argument out in the front yard) raises the same questions that have often been leveled at the Maysles brothers for films like Salesman and Grey Gardens – what are the ethics of exposing people’s private lives in this way? To what degree is this permissible because the subjects themselves are complicit in what is being shown? In short, are the filmmakers exploiting people for an audience’s amusement?

Richert explains in his commentary that Mike and everyone else in his life were completely willing participants, that in a sense they welcomed the attention being given them by the filmmakers. Each scene was discussed before filming (including that confrontation with the other woman, who agreed to take part because she was cheerfully defiant about her illicit relationship with Mike – who, at other points in the film, is quite open about his womanizing). Kaylor’s method, as he explains in his commentary, was to set the scene in motion and then at certain points ask everyone to “hold that thought” while he quickly changed angles, and then resume shooting as they picked up their discussion or argument where it had broken off. That is, he didn’t “direct” the content of the scenes, but he didn’t hold back and try to be a silent, unnoticed observer. What the participants expressed was true to their feelings, but they were also channeling those feelings through a kind of performance. How much did the presence of the filmmakers trigger or alter the content of their interactions? That’s a question which hangs over all observational documentary; as science acknowledges, observation inherently affects what is being observed.

What separates a good documentary from a bad one is almost always the impression the viewer gets of empathy on the part of the filmmaker for the people being filmed – that is, in the end, a completely subjective thing. There have always been people who condemn Grey Gardens for what it exposed of the two eccentric, reclusive women whose lives the film depicts. But the making of that film did something to transform those lives, making Little Edie something of a celebrity who emerged from her original seclusion and arguably had a more rewarding life after the film was released.

There’s no indication here about what impact Derby had on Mike and his family. But we’re told that Charley O’Connell was upset by it. What had started out as a movie about the sport he’d dedicated his life to ended up focusing on someone who comes across as something of a deadbeat who fantasizes about that sport as his way out of a life which seems pretty hopeless. By mixing roller derby with Mike’s life, there’s a risk that the film could be seen as mocking the sport … which was how O’Connell apparently viewed it. We are told, however, that the response to a screening in Dayton was quite positive … which raises another point about observational documentaries which is not always acknowledged: while a viewer may feel uncomfortable peering into other people’s lives like this, sometimes the people being observed find in the exposure a sense of validation.

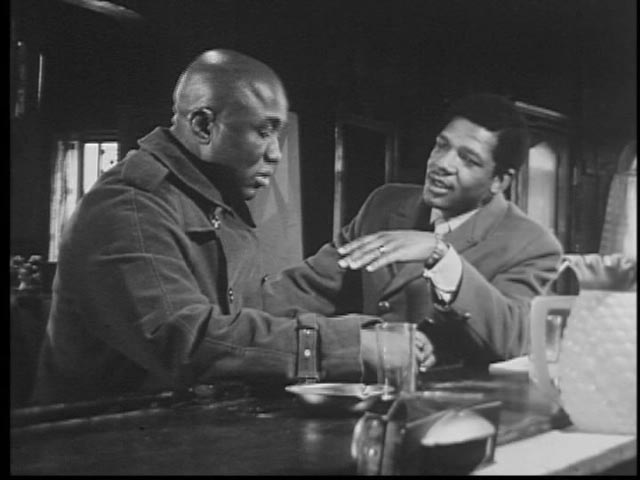

The Code Red DVD of Derby has an appropriately raw look – the transfer from a 16mm print is typically contrasty with pronounced grain, and there are scratches and dirt visible throughout – but the film itself is greatly enriched by those two commentary tracks. And as if that wasn’t enough, a second short feature by Kaylor is included. Max-Out, made the previous year, is a mix of drama and documentary in which the story of a man recently released from prison is improvised by a cast made up largely of ex-cons. Shot in black-and-white, it follows Melvin Rivers (his own name) as he arrives in Brooklyn after being locked up for three years; he wanders aimlessly, looks up old acquaintances, finds a place to stay with a gay man who he eventually rips off, resists pressure to get back into petty crime … but really has no viable options (an attempt to get hired by a temp agency falls through the moment he admits he’s been in prison). It’s a bleak slice of life created by people who have experienced that life. There’s an additional commentary by Kaylor on this film.

Strangely, after directing and photographing these two films, Kaylor’s next credit came nine years later with the feature Carny (1980), starring Jodie Foster and Gary Busey, followed ten years later by Nobody’s Perfect (1990), starring Chad Lowe. It’s always curious to see promising work which seems to have led almost nowhere, particularly since Derby received a very positive critical response when it was briefly released in the early ’70s.

*

Terminal Island (Stephanie Rothman, 1973)

It’s a depressing fact that women have historically been such a rarity in the ranks of movie directors. In Hollywood’s “Golden Age” in the ’20s and ’30s, the only female studio director was Dorothy Arzner, who began as a scriptwriter, then editor, before making a series of woman-centred films. (In the early decades of the industry, many editors were women, partly because it was considered a fairly menial part of the filmmaking process; as it became more widely recognized as a crucial element of movie-making, women were largely edged out by men.) It was a half decade after Arzner’s retirement in 1943 before actress Ida Lupino began to direct, eventually making several films which pushed the limits of the Production Code – Outrage (1950), which dealt with rape; The Hitch-Hiker (1953), a tense noir about two men who give a lift to a man who turns out to be a serial killer; and The Bigamist (also 1953), a surprisingly sympathetic and non-judgmental story about a businessman with two wives, one in San Francisco, the other in Los Angeles.

With the studios still resistant in the ’60s and ’70s, women began to work on the fringes, in exploitation and even porn – Roberta Findlay and Doris Wishman, for instance. As the big studios declined and smaller companies gained a larger commercial foothold, a number of woman made genre movies for producers like Roger Corman – Barbara Peeters (Humanoids From the Deep, 1980), Amy Holden Jones (The Slumber Party Massacre, 1982), Kathryn Bigelow (The Loveless, 1981). One of the earliest of these was Stephanie Rothman, who began as an associate producer on a couple of Roger Corman’s repurposed Russian sci-fi movies – Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965), which cannibalized Pavel Klushantsev’s Planeta Bur (1962), and Queen of Blood (1966), which did the same for Mikhail Karzhukov’s Mechte navstrechu (1963) and Valery Fokin’s Nebo Zovyot (1959).

Rothman got her first shot at directing on what was probably the most reworked of the movies Corman bought from Eastern Europe. Operation Titian was directed by Rados Novakovic in Yugoslavia in 1963, but this rather thrill-less thriller about an art theft was deemed unexploitable by American-International, so Corman had Jack Hill convert it into a story about a murderous artist, and then handed it to Rothman who made the artist a vampire. (It’s not very good in any of its incarnations – under no less than four different titles: the original, plus Portrait in Terror, Blood Bath and Track of the Vampire – but taken all together it’s a fascinating study in the limits of what’s editorially possible; Arrow’s special edition Blu-ray contains all four versions of the movie.)

Rothman followed that job with a couple of soft-core movies, and then made The Velvet Vampire (1971), an attempt to update the traditional vampire story which drew on Harry Kümel’s Daughters of Darkness, released earlier that year, and acknowledged the influence of Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla by naming its vampire Diane LeFanu. An uneven film which had a rocky distribution history, it nonetheless stands as a notable example of the rethinking of traditional horror at the time. Following this, Rothman directed only three more features; squeezed between two sex comedies, she made her best movie in 1973.

Terminal Island is something like a low-budget riff on Peter Watkins’ Punishment Park (1973), stripped of the political arguments which were the core of that film. In a near future, after the abolition of the death penalty, people convicted of capital crimes are exiled to an off-shore island with a bare minimum of supplies. Needless to say, these killers and rapists form the most rudimentary of societies, ruled over by Bobby (Sean Kenney), a sociopath with the ability to subordinate and manipulate the others.

We’re introduced to this community through the eyes of Carmen (Ena Hartman), a recently convicted Black woman who quickly discovers that the few women among a mostly male group are considered property. Outnumbered, the women have little choice but to submit. That is, until they’re liberated by a small second group led by A.J. (Don Marshall), who have escaped from Bobby’s dictatorship and now survive by keeping on the move in the wooded hills. This group proposes an alternative, more egalitarian kind of social order. This is where the movie hints at then-current politics: with a couple of Black men being the main organizers, there’s a suggestion of revolutionary power rising up against white repression. (We aren’t given back stories for most of the characters, so at times it’s puzzling how these decent, likeable guys ended up condemned to the island.)

The main community eventually self-destructs through the increasingly deranged behaviour of the leader, a man incapable of conceiving of community as anything but something to serve his own needs. When war breaks out between the two groups, there’s nothing to hold his forces together while the outsiders are willing to sacrifice themselves for their companions. In the end, a new society is forged in which individual freedom is balanced by communal bonds, with equality of race and gender.

Which is not to say that Terminal Island is a high-toned tract – it’s a rough-and-ready B-movie garnished with sex and violence, efficiently directed and acted, notable mostly for turning the usual tropes of women-in-prison movies into something a little more progressive, offering a critique rather than mere exploitation.

There’s a commentary by a couple of the actors on the Code Red disk, along with two lengthy on-camera interviews with the same cast members.

*

Holiday in Spain (Jack Cardiff, 1960)

If it was possible to construct a coherent spectrum, Holiday in Spain (1960) would be at the far end from Terminal Island. Directed by the great cinematographer Jack Cardiff, this bloated movie was conceived purely as a means to exploit the Cinerama format. Invented in the early ’50s as just one of a number of technical innovations intended to save Hollywood from the encroachment of television, Cinerama was the biggest and most cumbersome. It involved shooting with three interlocked cameras to give an image which almost enveloped the audience with a 146-degree span. The three synchronized film strips had to be screened with three interlocked projectors; issues of alignment and sync could cause problems, with noticeable vertical distortion where the images overlapped.

Touted as a great leap forward, the format paradoxically reached all the way back to the origins of cinema in terms of content, emphasizing what is known as the cinema of attractions – that is, spectacle for its own sake. The signature image of Cinerama is the point-of-view shot from the front car of a roller coaster providing the audience with an overwhelming sense of motion and vertigo. Like IMAX decades later, Cinerama was generally used for travelogues, affording audiences a virtual experience of other places and impressive natural sights. Also like IMAX, it was occasionally used for dramas – but here too, the emphasis was on spectacle rather than narrative, perhaps best exemplified by How the West Was Won (1963), in which five episodes depict four generations of one family through the stages of 19th Century western expansion.

Holiday in Spain was originally called The Scent of Mystery in its initial longer cut, which also introduced Smell-o-Vision, a thankfully failed innovation which found its most successful iteration in John Waters’ Polyester (1981). The Redwind Productions Blu-ray from Screen Archives offers only the shorter version (cut by about sixteen minutes), but even at 109 minutes it’s a bit of a slog. The script by Kelley Roos and William Roos (credited on Wikipedia to novelist Gerald Kersh for some reason) is at best perfunctory, serving merely as an excuse to prop up a picturesque travelogue of Spain (which a featurette on the locations reveals to be geographically incoherent).

A mystery writer (Denholm Elliott) who has run out of ideas takes a holiday in Spain where he becomes mixed up in a chase to save a woman apparently being stalked by a murderer. There are lengthy stretches on the road as he criss-crosses the country in a cab driven by Peter Lorre. Elliott is a cipher and Lorre phones it in (though he does appear to be enjoying his working vacation in Spain). The narrative is so thin that by the end I honestly couldn’t recall what had happened, nor figure out exactly who was doing what to whom – the woman he’s pursuing turns out to be a decoy, but why someone would be trying to kill her (or pretending to try to kill her) is obscure; the real woman is revealed in only the final moments – an uncredited cameo by Elizabeth Taylor (no doubt a favour to producer Mike Todd Jr., son of her late husband Mike Todd).

The story is weak and the images of Spain only mildly engaging. It wasn’t even a genuine Cinerama production, having been shot in 70mm Todd-AO and converted in post-production. The disk represents an impressive effort at restoration – taken from a number of compromised sources – but it’s not too surprising that the movie isn’t well-known; beyond the format, it has little to offer. The disk presents the feature in a “smilebox” simulation of the curved Cinerama screen, which merely emphasizes the gimmicky quality of the movie itself.

There’s a commentary on the disk, along with several interviews and a couple of featurettes on the locations and the restoration. A second audio disk contains the score by Mario Nascimbene. There’s also a reprint of the entire original pressbook.

Comments