The art of silent film: Anthony Asquith’s Shooting Stars (1928)

Anthony Asquith was a child of privilege. His father was H.H. Asquith, the British Liberal Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916. Educated at Winchester and Oxford, Anthony was apparently a self-assured and convincing debater who was drawn to the relatively new medium of film, although he considered the state of British cinema to be dire. While Alfred Hitchcock, his contemporary, went to Germany to learn his craft, Asquith headed West, to Hollywood, where he spent some intense time meeting and observing such major figures as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish and, perhaps most importantly, Chaplin.

Returning to England, he was determined to transform the native industry. As Henry K. Miller puts it in the booklet accompanying the new BFI edition of Asquith’s first feature, Shooting Stars (1928): “Asquith had written bluntly of ‘the peculiar badness of the average British film.’ Whereas others attributed it to the industry’s weak finances, Asquith zeroed in on ‘the incredible lack of film sense shown by most English directors, who usually choose to tell a much more than twice-told tale in a procession of overladen sub-titles sparsely illustrated by an occasional photograph.’” To counter this, Asquith wrote a number of scripts which he tried to promote, unsuccessfully, to various production companies.

In 1927, he did manage to make an entry into the business as co-writer and assistant editor on Boadicea, a historical film about the fierce queen who stood up against the Romans in the first century A.D. This was produced by British Instructional Films, a company struggling to survive at the studios of the Stoll Film Company in Cricklewood, on the outskirts of London. While doing various jobs around the studio (including performing as a stunt double), Asquith managed to get the company interested in one of his scripts. Ironically, it was set at a film studio (and written specifically for Cricklewood) which produces exactly the kind of movies he detested.

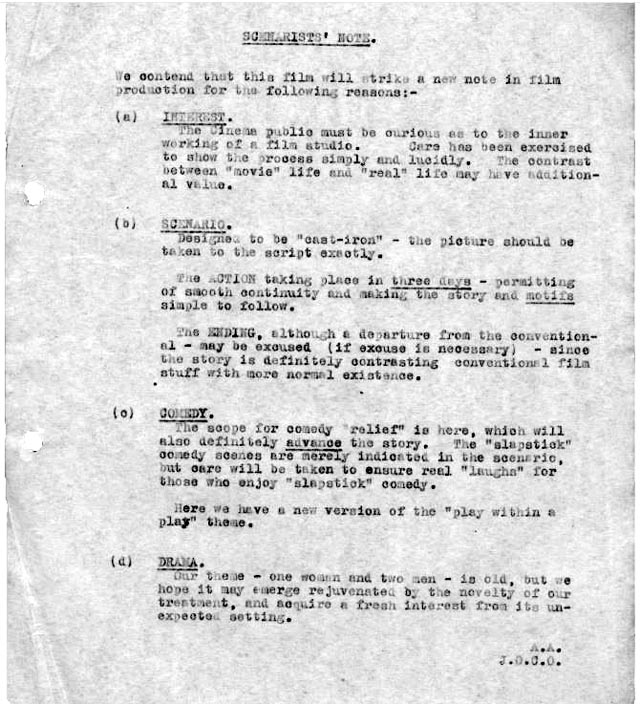

According to the BFI’s notes, the on-screen credits for Shooting Stars are inaccurate: while the story is attributed to Asquith, the script gets him a co-writer credit with J.O.C. Orton, who was initially announced as director. Eventually Asquith was assigned as co-director alongside A.V. Bramble, who receives the sole screen credit, even though it was known at the time that he was essentially there to “supervise” Asquith, who did the actual directing. The BFI disk includes a PDF of the shooting script and it’s interesting to note that Asquith had described in detail on paper every shot and camera effect which is seen in the finished film, leaving little doubt that this is indeed his movie.

My initial impression of Asquith, formed many years ago, as the director of elegant adaptations of major plays – Pygmalion (1938), The Winslow Boy (1948), The Browning Version (1951), The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) – seemed to accord with his privileged background. I eventually came across a number of other, smaller films he made during and after the war and, while these were of varying quality, they gave the impression of a solid, sometimes stylish journeyman – the wartime comedy Cottage To Let (1941); the propaganda films Freedom Radio (also 1941) and Uncensored (1942); the war films We Dive at Dawn (1943), about a submarine mission, and The Way to the Stars (1945), about life on and around an RAF base in the middle years of the war; The Woman in Question (1950), an excellent minor murder story with a complex flashback structure; and Orders To Kill (1958), a return to the War with a much more complicated perspective on the moral issues involved in killing.

But the real revelation came with a chance to see Asquith’s fourth and final silent feature, A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929), a film which uses the full resources of silent storytelling in richly imaginative ways, playing with audience identification (including a remarkable sequence set inside a movie theatre which is played entirely on audience reaction to what is happening on the unseen screen). Here was a filmmaker using every visual tool available to him to tell a story of romance and jealousy, sexual obsession and attempted murder; it was difficult not to believe that the advent of sound had undermined Asquith’s abilities, replacing complex visual strategies with the fairly straightforward recording of people exchanging dialogue.

This impression was only reinforced with the BFI’s release of Asquith’s second feature (and the first on which he received a director credit), Underground (1928); once again, the subject is romance, sexual obsession and jealousy, conveyed through a mix of documentary and expressionist imagery and, at times, quite radical editing. It was clear that Asquith had learned well from his observation of American, European and Russian films and, like Hitchcock, did a great deal to break British cinema out of its dreary stagnation.

What is even more remarkable is that this talent should have sprung full-grown from Asquith’s passion for film, even before he directed his first shot. The scenario for his first feature, Shooting Stars, is not only an intricately structured story of (yes again) romance and jealousy; it is a meditation on the nature of the movies, the connections between real and imaginary life and the ways in which screen fantasy informs and even shapes real emotions … as well as a sophisticated critique of the mediocrity of the kind of movies routinely produced in England, its own complexity offering a thorough refutation of the laziness so deeply embedded in the industry. His criticism was of prevailing technique, not necessarily of content. As he put it in his notes prefacing the scenario: “Our theme – one woman and two men – is old, but we hope it may emerge rejuvenated by the novelty of our treatment, and acquire a fresh interest from its unexpected setting.”

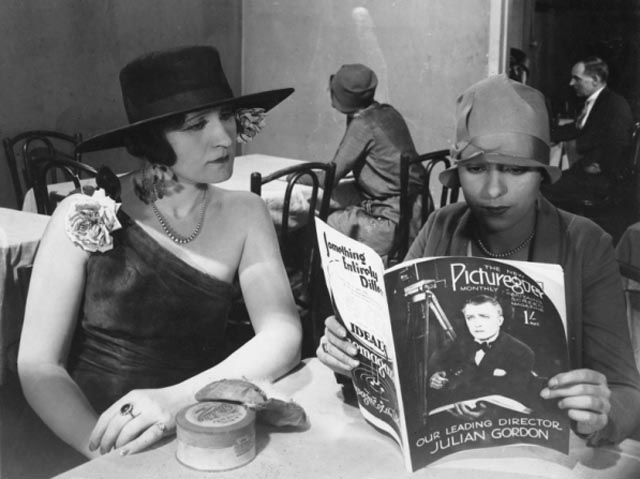

The central story thread is a romantic triangle. Self-absorbed star Mae Feather (Annette Benson) is married to her co-star Julian Gordon (Brian Aherne), but is involved in an affair with popular comedian Andy Wilkes (Donald Calthrop). Wilkes is being lured away by Hollywood and he wants Mae to go with him; she actually signs a contract with American producers, but it includes a morals clause which binds her to do nothing which would bring disrepute on the company or sully her public image. When circumstances reveal the affair to Julian, Mae feels trapped and takes a desperate measure to free herself, but the plan misfires tragically; the film concludes with a surprisingly bleak sequence which contrasts the harsh realities of life with the concocted illusions of the screen.

Every narrative detail is carefully constructed to create an increasingly intense series of echoes between the “real” lives of the three performers and the comedic and melodramatic lives of the characters they play in the pair of films we see being produced on the studio’s stages and out on location. Mae and Julian are starring in a hokey western romance which would have looked cliched in a D.W. Griffith short from 1910, while Wilkes appears as a sub-par Chaplin-like character in a slapstick comedy whose plot parallels his own situation with Mae and Julian.

The “meta” aspects of Shooting Stars peak in a sequence in which Julian goes to the movies and watches one of the melodramas he and Mae have starred in. Surrounded by a boisterous and appreciative audience, he himself reacts emotionally to the excitement on screen as his character races to save Mae’s character from a “fate worse than death” at the hands of the villain. Here Asquith captures the strange paradox of the very real emotions we all feel as we watch what we know are made up stories and simulated feelings conveyed by a play of light and shadow reflected on a screen in a darkened theatre. The situation involving Mae, Julian and Wilkes is just as contrived as the situations in the films-within-the-film, and yet by the end we find ourselves caught up in the emotional turmoil and the film’s final sequences, brilliantly directed, attain a level of tragedy which belies the absurdity of the whole made-up situation.

What Asquith understood so well was that, in movies, what mattered was not what you said but how you said – or rather, showed – it. Shooting Stars is filled with beautifully considered visual moments, often in remarkable long shots which powerfully enhance rather than diminish the characters’ emotional states. The scenes inside the studio and out on location are often extremely wide, with action seen from a distance, emphasizing the artificiality of what the performers are doing by situating it in a much larger, more real world. And yet these shots, particularly those in the studio, have as much expressionist power as they do documentary verisimilitude. While the core story is recognizable as a fairly standard melodrama, Shooting Stars is also a revealing document of just how movies were made in the silent era.

Early in the film, there’s an elaborate crane shot, taken from close to the sound stage roof, which looks down on all the bustling activity on the stage floor, with Mae weaving her way past the crew and equipment and climbing stairs to a secondary level where we see a second film being shot simultaneously. This is a comedy starring Wilkes. Off to the side of the set is a small jazz combo providing mood music for the performers involved in a slapstick scene. The seeming effortlessness of this shot, crowded with activity and the busy-ness of production, subtly establishes through visual connections between the two levels, the two films being shot, and the three characters whose real lives intersect on and off screen, what we will come to see as the conflicted triangular relationship at the heart of the film. It reveals Asquith as a genuine visual master in full control of the medium.

Late in the film, there’s a smaller, yet comparable shot, in which we see Mae, now all but forgotten and reduced to the status of a day player, waiting in the studio cafeteria to be called to set to provide some background detail. On set, we see a group of people gathered in a huge cathedral and as they turn to leave, the lone figure of Mae, seen from behind, walks up the aisle past them, shrinking into the distance towards the altar. But as she goes, the camera slowly cranes down and we discover that the entire cathedral is a glass painting hung just before the lens, and beyond it the foreshortened pews lie in the middle of the cluttered soundstage floor. This is a remarkably bold shattering of illusion, revealing a major trick which had been, and would continue to be, used to fool the audience’s eye. But more than simply exposing that trick, the shot serves to make Mae’s situation more pathetic, leading to the devastating line of dialogue on the final intertitle card; what could have been a mere gimmick is, in Asquith’s hands, a powerful emotional tool and a revelation of film’s ability to use artifice to create genuine feeling.

*

The disk

The BFI restoration of Shooting Stars is very impressive, with an image taken from multiple sources and pieced together in places frame by frame. The photography, quite apart from the occasional complex moves, has terrific depth and detail, giving the film a real sense of scale and a variety of moods. The newly commissioned, jazz-inflected score by John Altman gives the film more energy than a more “traditional” piano accompaniment might have, although there were a few times when I found it a bit exhausting.

The supplements

Beyond the film itself, the disk has a wealth of supplements which provide interesting insights into film production in the late silent period, many of them dealing with the Stoll Film Company itself and the studios at Cricklewood, as well as British Instructional Films

Pathe’s Screen Beauty Competition (2:00, 1920), The Lovely Hundred (:25, 1922) and Starlings of the Screen (15:00, 1925) all focus on the dream of stardom, with studio contests attracting young women to try out for screen tests. Here we glimpse the intersection between the business of movies and the well-sustained illusion the public held of that business.

Meet Jackie Coogan (11:00, 1924) follows the 10-year-old star on a publicity tour in aid of orphans, including a visit to the Cricklewood studios. Coogan seems remarkably self-possessed, and always aware of his relationship to the cameras recording his activities.

Opening of British Instructional Film Studio (4:00, 1928) records the inauguration of the company’s new studio at Welwyn Garden City in November 1928, with hundreds of employees arriving by train to walk across a muddy field towards the huge building, inside which they listen to a speech by the Right Honourable L.S. Amery.

Around the Town: British Film Stars and Studios (2:00, 1921) shows that public interest in how movies were made was well-established years before Asquith made his feature. We see director Charles Calvert guiding actress Josephine Earle through a scene, followed by a glimpse of the studio’s power plant which provides the light for the stages.

Perhaps the most interesting supplement, though, is Secrets of a World Industry – The Making of a Cinematograph Film (8:00, 1922), which begins with an explanation of how the sprocket holes are punched into the film strip, then follows the processing and printing of the exposed negative, the making and editing of positive prints, and finally boxing up and shipping those prints for distribution. It’s a fascinating glimpse of a physical process which has now all but vanished as filmmaking has become more technically sophisticated and computer-based.

There’s also a gallery of stills and publicity materials (6:00), a PDF of the original script, and a booklet with several informative essays about the industry, the film itself, Asquith, and the new music score.

The Shooting Stars Blu-ray is destined to be one of the highlights of 2016.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) (October 5, 2018) In a comment posted below, Chrystine Walter informs me that the initials “J.O.C.O.” below Asquith’s “A.A.” on this page indicate that the director collaborated with her grandfather, John Overton Cone Orton, on the film’s scenario. Born in London in 1889, J.O.C.O. was a prolific screenwriter and occasional producer, director and editor from the mid-1920s to the mid-’40s. (IMDb lists his last, uncredited, work as contributing to Alfred Hitchcock’s propaganda short Bon Voyage [1944].) (return)

Comments

Hi re this Shooting Stars review. Great to see your sentiments expressed mirror mine.

Any chance that you could give some credit to my grandfather John Overton Cone Orton, the JOCO you can see on the script where he and AA talk about ‘we’? As an under credited but amazing man JOC was also known as John. Bryony seems to have given him more credit as part of the creative and talented cast and crew of the film.

Thanks for this information, Chrystine. I’m afraid I didn’t know anything about your grandfather, although I see that he was assistant director on The Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands, which is a film I’m familiar with from the BFI’s Blu-ray release.