Disk discovery: Paul Fejos’ Lonesome (1928) from Criterion

For several years now, there have been dire predictions of the inevitable demise of movies on disk. In a world rapidly assigning more reality to the digital “cloud” than to actual physical objects, disks are supposedly quaintly old-fashioned. People, we are told, want instant access to everything on whatever device they happen to have closest to hand. And, indeed, there do appear to be quite a few people who are more than happy to watch a movie on a 5-inch smart-phone screen – though whether that actually constitutes “watching a movie” is clearly open for debate.

Streaming is the way of the future, we are told. But as the recent announcement by Netflix of its change of mission indicates, there are serious drawbacks for anyone who has a passion for anything more than the latest mainstream release. One of the things which encouraged the rapid expansion of the Netflix share of the home video market was the company’s promise to make available pretty much everything which had ever been made and a lot of people were drawn to their catalogue of classic movies and old TV shows.

But now they’ve announced a change of direction, a desire to become “the HBO of the Internet”, focusing more on new releases and original programming. Though their concept of original is a bit dubious. Their first, and unquestionably highly successful, venture was the recent House of Cards series. This was actually an American remake of a 1990 BBC series about behind-the-scenes political scheming. Netflix based their decision to do the Kevin Spacey-starring remake on algorithms which tracked viewer behaviour, putting together an apparently popular show with an apparently popular star and an apparently popular filmmaker (David Fincher). If this is actually the future of “original” programming, a mash-up of ingredients already familiar to the audience, then it doesn’t bode well for genuine creativity.

But more importantly, the switch in direction points to the most serious limitation of a non-physical, streaming-movie utopia: Netflix has already pulled many of the older movies and shows from their roster, depriving fans and faithful viewers of much of what drew them to the service in the first place. Of course, disks regularly go out of print, but the objects remain and are usually fairly easy to find from various on-line sellers. But more importantly, once you possess a physical copy of a movie, you’re free to watch it any time you feel like it, with no risk of discovering, when the mood takes you, that some faceless corporate employee has made it disappear.

It’s this power of companies to withdraw availability which makes it almost certain that there will continue to be demand for disks (and books for that matter; people have already discovered that the “right to read” an ebook they’ve paid for can be withdrawn at the whim of the company which sold it). That demand won’t be on the level of the early days of DVD, perhaps, but still at a fairly stable rate. Even as larger distributors have been cutting back on their investment in the disk market, others have found ways to exploit the continuing demand. Warners was something of a pioneer with the Warner Archive Collection, a burn-on-demand service, which has expanded enormously since it was started four years ago. There are hundreds of titles available and more added all the time, increasingly remastered to a higher quality (they’re now even trying out the idea of burn-on-demand Blu-rays). This model has been followed, so far without the same degree of success and perhaps too often without the same attention to quality, by other companies – Sony, MGM, Universal, Fox. One of the downsides is the typically rather high price.

But the bigger downside is the loss of the kind of supplementary features once common on DVDs, which provided context for the movies. These were, apart from the quantum leap in quality from VHS to disk, the biggest boon for movie fans; in the first decade of movies-on-disk, a fascinating and quite detailed history of the art and business of movies was becoming available for those who were interested. This kind of material is virtually unknown in the “cloud” model. And it’s just one more reason that disks will continue to exist for a long time to come, although increasingly limited to smaller specialty companies, more specifically targeted at collectors – like Criterion, Kino, the BFI, Masters of Cinema at the higher end of the art, and Severin, Shout Factory, Olive Films, Twilight Time, etc, a little further down the scale.

These companies don’t mass produce the way the majors used to, but they serve that audience which not only loves movies but wants to understand the history and context of what they watch.

Paul Fejos’ Lonesome (1928)

Take for instance Criterion’s recent release of Paul Fejos’ Lonesome (1928). I hadn’t actually heard of Fejos before this release, although the film comes from a period I find particularly interesting – the transition between the peak of silent cinema and the beginnings of sound. This technological shift had a massive impact on filmmaking largely because the remarkable visual freedom of late silents was suddenly undermined by the physical limitations of the cumbersome new equipment for sound recording.

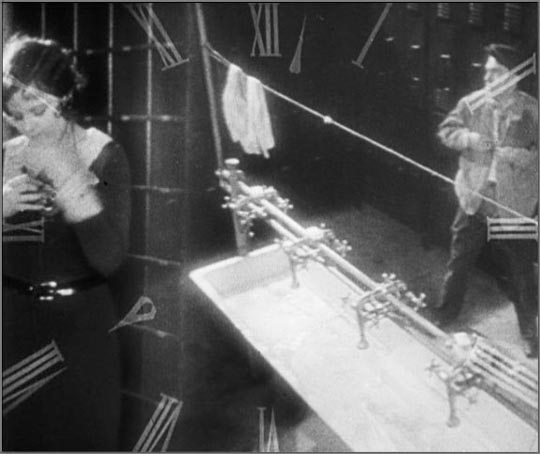

Lonesome, in fact, is a fascinating illustration of this process because it was started as a silent and, after the fact, transformed into a partial talkie. The opening section of the film is a stunning display of visual invention and complex montage as Fejos gives us the parallel lives of Mary (Barbara Kent) and Jim (Glenn Tryon), two lonely people living in New York; we see them rising on a Saturday morning in their tiny one-room flats, getting to work on the crowded subway, toiling at their meaningless jobs (he works in a machine shop, she’s a telephone operator). The extended montage, heavily influenced by the city films of Dziga Vertov, Walter Ruttmann and others, gives a remarkable sense of the almost overwhelming busy-ness of city life, existence among a bustling population, but within which the two are completely isolated and alone.

With work ending at midday, Jim and Mary are drawn into the general holiday flow towards Coney Island where Jim spots Mary and follows her; she sees him and toys with him, slipping in and out of the crowd, until eventually they meet and settle on the packed beach. Here, abruptly, the free-flowing energy of the film (Fejos is adept at keeping things moving in the crowd) stops dead; even the hectic background falls still as Jim and Mary suddenly begin to speak. This, the first of three talking sequences, is awkward and stilted and, seen from our perspective, completely unnecessary. Nothing is said which couldn’t be conveyed in titles. But the changing market of 1928 insisted that this was a necessary “improvement” to satisfy customers still in thrall to the novelty of sound. With that sense of novelty no longer affecting us, what we notice is the drastic shift in the film’s energy, the sudden loss of the momentum which has been propelling the two characters towards each other.

In between these talking sequences, the film resumes its free-flowing imaginative movement, but the three interruptions damage it on an artistic level; it doesn’t hold together creatively the way, say, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) does. The two production modes are at odds and Lonesome as a whole isn’t completely satisfying.

Criterion’s disk supplements

If this was all that Criterion had to offer on the disk, Lonesome might remain little more than an interesting curiosity by a previously unfamiliar director. But, as is often the case with this company, the disk has extensive supplements to illuminate the context of the film. There’s an informative commentary track by film historian Richard Koszarski, who fills in a lot of detail about the circumstances of the production (even suggesting that one of the talking sequences, a highly stylized colour sequence, might actually have been directed by someone else).

There’s a fascinating audio reminiscence by Fejos about his entire career, illustrated with photos; trained as a doctor in his native Hungary, he was attracted by film and made a few before emigrating to New York, where he directed an experimental feature, now lost. That film, The Last Moment, landed him a contract at Universal, with the company pretty much giving him carte blanche. After several years in Hollywood, a place he disliked, he eventually returned to Europe and became an anthropologist, making ethnographic films and running academic conferences. Of course, none of this would be apparent simply from viewing Lonesome as an isolated artifact.

There’s also a short piece with cinematographer Hal Mohr, who worked with Fejos on the later Broadway (1929), discussing the massive, innovative camera crane built for that production (and the big soundstage which had to be built to accommodate it).

Even more generous than usual, Criterion also offers two other complete features directed by Fejos. Both made in 1929, the first (and shorter) is silent: The Last Performance is the most conventional of the films on the disk, a melodrama about a great stage magician (the always fascinating Conrad Veidt) who falls in love with his pretty young assistant, whom he hopes to marry when she comes of age. But she falls for someone her own age and the magician realizes that he’s lost her, so he commits a murder under the eyes of a packed theatre, managing to make it appear that her boyfriend is the killer. But he’s not a really bad man and at the trial finally demonstrates his trick, condemning himself and freeing the young lovers.

The other feature, Broadway, is one of those fascinating early talkies which hasn’t yet settled on a particular genre. The film (released in both silent and sound versions), begins with a high angle panoramic view of New York centred on Broadway and Times Square; seamlessly, this view becomes a vast, detailed miniature of the same scene, complete with moving traffic, into which a giant demonic figure strides, slopping alcohol all over the streets below, possibly Bacchus spreading his intoxication, but reminiscent of the devil in Murnau’s Faust, the epitome of corruption. Following this unusual (for an American film) opening, Broadway takes place almost entirely inside a vast (almost surreal) New York nightclub.

There was a kind of looseness bordering on chaos in those early years, with filmmakers jamming as many elements in as they had time for (an approach still often in use in Bollywood). Broadway is a romantic comedy, a musical, a gangster film, a murder story, all revolving around the prickly relationship between performer/choreographer Roy Lane (Glenn Tryon again) and Billie Moore (Merna Kennedy), the girl he loves with whom he’s been developing a new routine which he hopes will propel them to the big time … but until they make it, he refuses to declare his love. And meanwhile Billie is stepping out with slick gangster Steve Crandall (Robert Ellis), who obviously doesn’t have honourable intentions, but she’s attracted by his money and uses him to provoke a reaction from Roy.

As this triangle plays out, there’s a murder, a cop snooping around backstage, a chorus girl bent on revenge, and a series of big cabaret numbers which are filmed from that huge crane, the camera swooping around the multi-level set in defiance of the static dictates of early sound recording. Fejos, like the great directors who seized the new technology and incorporated it into their creative arsenal (Hitchcock, Lang, Mamoulian), shows that an inventive filmmaker remained master of the medium in spite of the fussy technicians who insisted that their concerns must now take precedence.

In addition to the arrival of sound, these films also illustrate the complicated advent of colour. Lonesome contains several instances of elaborate hand tinting – the Coney Island fair at night; the burning wheel of a roller-coaster car when its brakes fail; and that highly stylized second sound sequence in which the couple declare their feelings in what seems to be a strange space outside of time and separate from the quotidian world which the rest of the film inhabits. Even more elaborately in Broadway, the ending abruptly bursts out in bright two-strip Technicolor, adding a different kind of artifice from the expressionist sets in which the film plays out. In these two films, we can see Fejos pushing the medium towards its inevitable technical future.

In their edition of Lonesome, Criterion have provided not only three interesting, entertaining movies and a valuable introduction to their creator, Paul Fejos, but also a compact lesson in what happened during one of the most turbulent transitional periods in film history. This is the kind of thing disks were made for. Streaming lets you watch a movie on whatever screen you might want (phone, computer, HD TV), but it’s never likely to give you the kind of richness this one disk offers. And that’s why there’s going to be a market for these small shiny objects for some time to come.

Comments