Winnipeg’s vanished movie theatres

Quite unexpectedly, a few weeks ago, I received an email inviting me to give a speech. To make it even stranger, the invitation came from the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, the organization which oversees the performance of hospitals in the city. My initial thought was that this must be a mistake. But it turned out that the person organizing their annual Christmas lunch for staff and board members knew about the documentary I made a couple of years back about all the long-gone movie theatres in the city and was aware that the WRHA’s new office building had been erected on the site of no less than three of those theatres. So the theme for this year’s lunch would be movies, movie-going … and vanished theatres.

What with my move to a new apartment and working full-time, plus the fact that I’m not much of a public speaker, I was inclined at first to say no, but a friend who likes to push me out of my comfort zone wouldn’t hear of that. So after a day of mulling it over, I agreed. It took about a week to write the twenty-odd minute speech, based on my documentary and the research I had done while making it.

The lunch was last Friday and it turned out to be a very congenial affair with about fifty people in attendance. The food was good and, apart from the fact that I spent much of my presentation looking down at my papers and reading, rather than up at the audience, it went over well. I even managed to sell quite a few copies of my DVD.

At the end of the event, the organizer asked everyone in the room to name a favourite movie and say how many times they’d been to a theatre this past year. While some still go quite frequently, many – like me – hardly go at all any more. One even prefers to stay home and watch old VHS tapes. As for favourite movies, I began to feel quite old as a number of them named Star Wars as their first significant experience – and all of them were eagerly waiting for J.J. Abrams’ reboot to open this Friday; while many others named movies from the ’80s – John Hughes was popular. I was gratified when someone named Kore-Eda Hirokazu’s After Life as a favourite.

While I’m always made uncomfortable by the question (I’ve seen so many movies and like so many for different reasons, that it’s impossible to name a single one), I decided to go with one of my absolute favourite comedies, Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve, one of the few perfect movies I know.

Below, for what it’s worth, is the text of my speech.

I’d like to thank you for asking me here to speak about a subject which means a lot to me …

But I should apologize up front that there may be moments when I sound like a cranky old man reminiscing about the good old days. What I’m about to say is steeped in nostalgia because I’m going to be talking about something quite wonderful which no longer exists: the strange experience of going to movies when movies were something more than over-hyped commercial product. Of course, they were that – but they were more than that. There was a time when going to the movies transcended the purely commercial … and that’s what I’m here to share with you today.

Movies have been a big part of my life – I’ve worked on them, made some of my own, have written about them for decades and continue to do so. But today, I’m going to talk about not the movies themselves, but rather the theatres in which they played and the experience those special places provided, an experience which meant so much to me that I even made a documentary about it a couple of years ago, drawing on the memories of many Winnipeggers who share my passion.

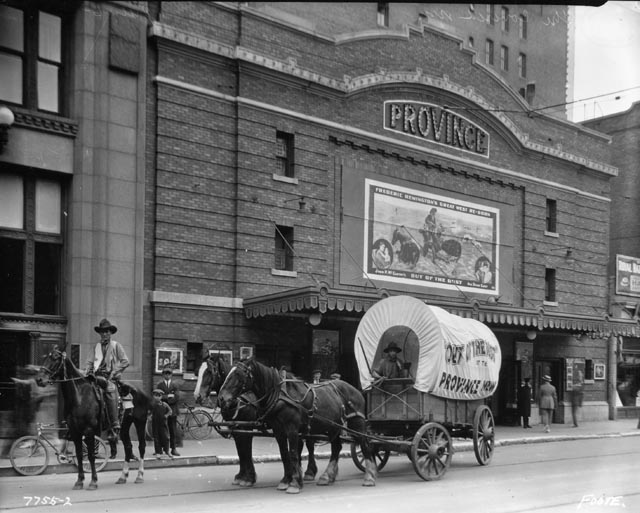

In the movies’ first century, more than a hundred theatres came and went in Winnipeg. Some appeared just briefly, while others lasted up to six or seven decades.

As you just heard, this very building was erected on the site of no less than three theatres.

There was the Starland, built in 1909 as the Royal, which closed its doors in 1967, although the building remained standing for decades, turned to other uses. The Colonial was built around 1910, and finally closed its doors in 1974.

Then there was the Regent, built in 1913 as the Rex, one of the first in all of Canada dedicated solely to screening movies, with no live vaudeville to support the show. In 1978, it was renamed the Epic, which became famous for its long-running midnight screenings of the Rocky Horror Picture Show. It finally closed in 1986.

But while three theatres side by side on one block may seem excessive, there were in fact eight theatres in just a five block stretch here on Main Street, including one just across from here at the corner of Logan and Main. The Oak was built in 1938 and lasted until 1962, and urban legend had it that you could get in for half price if you brought your own apple box to sit on.

One of the people I interviewed for my documentary made a special trip to the Oak just to check out that rumour, and she assured me that the theatre did in fact have regular seats. Another of my interviewees actually carried an apple box down there, but was told by the manager that he would still have to pay the full price.

Even though dedicated theatres were being built as early as 1910, many picture shows were originally offered in vaudeville houses, screened between live acts. Others would be set up in empty storefronts by enterprising people looking to make a fast profit.

Right from the first, this sideshow atmosphere gave the movies a slightly dubious image, which was amplified by their appeal to the “lower classes”. As a form of entertainment they were in a sense socially democratic – cheap, easy to understand, even for immigrants who spoke little or no English. They didn’t have the same cachet as live theatre or music recitals and the powers-that-be felt a need to keep an eye on them.

For instance, there’s a letter in the city archives from the Chief Constable to the Mayor and Council about attendance at “moving picture theatres” at 9:00 PM on the night of Saturday, November 29, 1913 – and I quote:

“As per your phone request to a member of my staff, on the night of Saturday, the 29th, I beg to report for your information that at 9 p.m. the two Picture Houses in Fort-Rouge had an audience totalling 570 persons. The North End Division, which includes everything North of the C.P.R. Railroad, reports at the same time having a total audience at Picture Shows of 1475 persons. The Central Division, which includes all that part of the City of Winnipeg between the Assiniboine River on the south and the C.P.R. Railroad tracks on the North report at the same time having a total attendance at Moving Picture Shows of 11,200. The District of Weston, in which there is one Moving Picture Show located had on Saturday, the 29th 350 persons in attendance, being a total number of 13,595 attending Moving Picture Houses at that time.”

With a population of around 140,000 at the time, this means almost ten per-cent of the population were at the movies at 9PM that evening. With those kinds of numbers and the dubious image of the movies, it was inevitable that the city’s moral guardians would keep an eye on what was being shown. Starting as early as 1912, there were three censors, each having the task of visiting the film exchanges to view prints and make judgements, cutting out anything deemed unfit or offensive.

In the censors’ monthly report for April 1915, they passed 548½ reels and condemned 53½. The complaints ranged from burglaries, murders and suicides to blasphemy.

In a letter to the committee from License Inspector Frank Kerr on May 22, 1912, Mr Kerr reported in detail on three disputed films, concurring with the original censor’s decision to ban them. I’ll just read the description of one[1], called The Chocolate Revolver, to illustrate the censors’ concerns:

A man buys his little daughter an imitation revolver made of chocolate and shows her how to hold him up. He then leaves the house with his wife for the evening, and their servant, as soon as the child is asleep, also goes out.

Two burglars enter the house through the window and one of them upsets a statue which awakens the child, who gets out of bed and goes downstairs and is held up at the point of a revolver by one of the burglars. He tells her to go ahead of him upstairs and show him where her mother’s jewels are kept. She leads him to a cupboard and tells him they are hidden there; while he is looking for them she closes the door and locks him in. She then goes to her room and gets her chocolate revolver and goes downstairs where she surprises the other burglar who is wrapping up the silver. She holds him up and telephones to the Police.

While off her guard he seizes her and grabs her chocolate revolver. He then ties a handkerchief round her mouth and stuffs her under the sofa. Meanwhile the Police enter and are in their turn held up by the burglar and made to go into a room and are locked in there.

The father and mother shortly after arrive and enter the room and are also held up; however, the little girl gets out from under the sofa and opens the door of the room where the Police are. They come out and capture the burglar. They then proceed upstairs and the girl opens the cupboard door in which she had locked the other burglar. He is also captured.

Objections

Burglary and too much use of a revolver. Rough handling of a little girl.

As the business of movies got bigger, with prestigious features like Birth of a Nation becoming huge money-makers, and with movie stars becoming major public figures – Chaplin and Keaton and the Gish sisters and Valentino – more money was invested in theatres, and in the late teens and early twenties opulent downtown picture palaces were built in every city.

In 1920, the Allen family built an 1800-seat theatre on Donald Street, just south of Portage Avenue. The next year, Famous Players built the even larger Capitol, with almost 2000 seats, just a block away to the north. The Allen family were bought out by Famous Players and their theatre was renamed the Metropolitan in 1923. The first talkies in Winnipeg played at the Met in 1928.

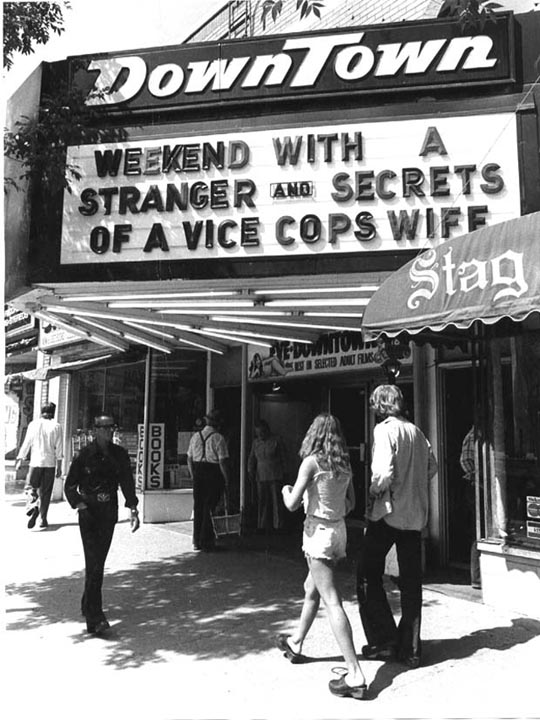

Many theatres went through several incarnations. Like the Gaiety, at the corner of Portage and Colony, built in 1912 and eventually specializing in Disney movies – until it was transformed into the Eve in 1973, showing exclusively soft-core porn. That lasted just two years, before it became respectable again as the Colony until it closed for good in 1985.

The Walker was a different case; built as a legitimate theatre in 1907, it was converted into a movie theatre in 1945, becoming the local headquarters of the Odeon chain until it closed in 1990 and once again became a live performance venue.

Some theatres, like the Beacon on Main Street, actually continued to offer live entertainment into the ’50s and even the ’60s, while the Met and the Odeon hosted live music broadcasts by the Eaton’s Good Deed Club.

While the big downtown theatres had prestige, with people even dressing up for a night out at the show, numerous smaller, more modest theatres sprang up all over the city. In fact, virtually every neighbourhood had its own theatre from the ’30s through the ’50s. These were often owned and operated by families, staffed by mom and dad, with the kids selling candy and tearing tickets. They were second and third-run houses, showing movies which had exhausted their box office potential downtown.

Because they were firmly embedded in neighbourhood communities, these theatres had a fairly stable audience, drawing on the local population. But they were still a business and had to find ways to hold onto that audience. So they offered more than just movies. There were popular giveaways, with items of dinnerware handed out on ladies’ nights. You’d have to go back week after week to collect the entire set.

Then in the ’50s there was something called Foto Nite, where a patron’s name would be drawn and a money prize handed out – anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars.

One of the biggest functions of the neighbourhood theatres, though, was getting children out of their parents’ hair on the weekend. It’s unimaginable today, but small kids would head off down the street by themselves, nickels clutched in their hands, buy their tickets and popcorn, and spend their Saturday afternoon – or even their entire day – at the movies before finally heading home again by themselves in time for supper. One of my interviewees described leading her younger siblings down to Pembina Highway to go to the Garry Theatre – when she was about six years old.

There were cartoons, cliff-hanger serials, newsreels and a feature, or perhaps a double-bill, usually a cowboy movie or a jungle adventure.

And if that wasn’t enough entertainment, management provided additional activities – yoyo contests, talent contests, birthday prizes, raffles … giving away anything from a bag of popcorn to a live puppy. These matinees were loud and chaotic, with the staff barely able to control the unruly crowd. As the kids roared and threw flattened popcorn boxes at the screen, staff would threaten to stop the show and turn on the lights … and they sometimes did. But the next week the whole ritual would be re-enacted again.

For kids and their parents, the neighbourhood theatres were centres of social activity and the movies themselves, although created by Hollywood to be nothing but disposable entertainment, could serve a larger function. One of my interviewees described learning a lot about life and behaviour from the movies because they showed her a larger world outside that of her poorly educated immigrant parents. Another described her husband as a child going with his father, who didn’t speak any English, and translating and explaining the movie to his dad as it played.

One man, getting a job as an usher at the Met when he was sixteen, told me that the movies gave him a grounding in the arts – theatre, design, music – which served him well when he moved on to art school himself a couple of years later.

Back in those days a movie could be a different kind of event from what we see today – they didn’t open on four-thousand screens on the same weekend trying to claim the biggest-box-office prize. They would move more slowly, from larger centres to smaller, building anticipation as word of mouth spread.

The Uptown, on Academy Road, built in 1931 and eventually turned into a bowling alley in 1960, was legendary in the fifties for the Thursday night sneak preview. This was a screening of a big movie soon to open downtown – but the title wouldn’t be publicized. The audience wouldn’t know what they were going to see until the lights went down and the projector started running.

These “sneaks” were treated as a gala occasion, with people dressing up, excitement building as the auditorium filled, with members of the audience speculating about what the movie would be. Newspaper ads might offer cryptic hints, such as suggesting that this week’s “sneak” would be strong stuff and not for the faint-hearted. One of my interviewees described being allowed to attend his first sneak as a kind of rite of passage, a step towards maturity.

Building the Uptown in the early ’30s, by the way, had required a zoning variance and community consultations. There were many in the neighbourhood who objected to the business being built in what was then a strictly residential area. To soothe those who objected most strongly, the theatre offered them free admissions … perhaps for life!

We’re used now to having movies lingering for months on multiple screens at the multiplex, but in the days of all those single-screen theatres, most movies would come and go in a week, quickly replaced by the next show. At the height of my movie-going in the ’70s, I’d try to catch as many as I could, sometimes seeing five or six or seven different movies in a week because you never knew if you’d ever get another chance.

And back then, once you bought your ticket, you could stay as long as you liked … in fact, it was quite common for people to walk in in the middle of the movie, stick around until the next show reached the point where they’d entered, and then leave. I would sometimes sit through a movie twice in a row if I found it particularly interesting … or go two or more times in quick succession while it lasted because, before home video, there was a good chance you’d never get to see it again.

If a show did well, it would be held over for a “second big week” … and if it was really popular, it might stick around for a month or more. The Kings, at Portage and Berry, was famous for playing big musicals and keeping them for a year or more. Though that pleased the faithful fans, it proved frustrating for the local kids who, week after week, had nothing new to look forward to.

The anticipation of something new was a big part of the experience of movie-going. Seeing the posters going up outside the theatre, watching trailers before the feature – and in those days they tried to whet your appetite, not give away the entire movie. There wasn’t the saturation publicity we get now, so we knew far less about what we were about to see … there was more room for discovery and surprise.

Even the atmosphere inside the theatre was designed to create a sense of anticipation. The screen was concealed behind curtains. The audience filtered in, speaking in hushed voices. The lights would slowly dim and the curtains would rise as the beam of the projector light sprang to life. You had a sense that something was beginning, that you were making a transition from mundane reality into a space governed by imagination.

I can still recall the feeling of surprise that came with stepping out after a matinee into a bright summer afternoon, the world looking different because my head was still in that other space. It affected the way I’d see everything around me. I don’t get that feeling today because there’s no sense of transition at the multiplex.

When you walk in now, the screen is lit up with an abrasive stream of commercials and trivia and you barely notice the segue to the actual feature, and then at the end, the last scene is barely finished before the lights flare up and the staff come in to start clearing the litter. No matter how good the movie might be, it’s no longer permitted to exist on its own terms in that imaginary space.

But as fond as my memories of movie-going in the ’70s are, the truth is theatres were already in decline by then. This was a process which had begun in the early ’50s and accelerated through that decade and after. One of the major causes, of course, was the arrival of television and the sudden availability of visual entertainment in the living room. You didn’t have to go out and pay for it any more. This, combined with the postwar boom in suburban development and the movement of many people away from the inner city, depleted the audience for traditional movie theatres.

The studios fought back by offering technical developments which were more impressive than what could be seen on a small black-and-white TV – big screen formats like Cinerama and Cinemascope promised overwhelming imagery, combined with louder-than-ever stereo sound. Then there was 3D, although that turned out to be a short-lived gimmick in its first go round.

Perhaps more significant, at least from a sociological angle, was the increase in disreputable subject matter. With parents staying home, the audience was shifting more towards teenagers and their interests – sex, crime, violence and rock-and-roll became big money-makers. As many theatres closed in the ’50s, drive-ins proliferated. The quality of the movies didn’t matter because the kids in the cars generally weren’t even watching the screen.

But the big epics and the tawdry exploitation weren’t enough to stem the inevitable decline and by the late ’50s and early ’60s most of the neighbourhood theatres and many of those downtown had closed. For a brief period, say from the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s, things stabilized as the studios lost their power and more daring movies were being made, but the arrival of home video in the mid-to-late ’70s sealed the single-screen theatre’s fate.

In 1979, the magnificent Capitol was irreparably ruined when the balcony was split off as a second auditorium, an act of architectural and aesthetic barbarism that announced that the end was nigh.

In 1981, the city’s first two multiplexes were built – the seven-screen Eaton Place Cinemas with tiny shoebox-size screening rooms and the Towne 8 at the corner of Notre Dame and Princess. These new theatres offered multiple movies in smaller auditoriums where a single movie on one big screen was no longer financially viable.

With so much of the city’s population spread out in the suburbs, it was inevitable that this model would become the norm – a single central location with multiple screens and lots of free parking. The old theatres with their individual characters have long since vanished, and with them the more personal experience of movie-going. Theatres today are like shopping malls and big box stores, warehouse-sized buildings where we can go and consume our entertainment, along with nachos and arcade games in the lobby.

If you show up and your movie of choice is sold out, just pick another … it’s not like the old days, when we would have to line up on a snowy sidewalk for an hour to make sure we’d get in. And maybe for some, that’s better. But for me, the frozen feet and the clouds of icy breath were an integral part of going to a movie – sitting in the dark, with the images playing up there in front of me, I knew I’d entered another world and it was a thrill to stay in that world for a couple of hours, forgetting about the winter waiting outside for me to return.

The last thing I asked each of my interviewees was what did they miss most about these vanished theatres. Their responses were, of course, varied.

For one, it was the curtains, the anticipation as they opened promising a special experience.

For another, it was a sense of urgency, of knowing that each movie offered an ephemeral experience, that there may never be another chance to see it.

But for many, it was the lost sense of community, of gathering together with friends and strangers in a special place to share an experience. Somehow, that’s missing from busy, noisy multiplexes.

In Winnipeg, it may now exist only in a couple of very small theatres – the Cinematheque in Old Market Square and the new Bandwidth theatre on Ellice Avenue – which strive to offer an alternative to mere commercial consumption, treating movies as something with intrinsic value rather than as mere product.

As for me, I still love watching movies, but I seldom get out to see them in a theatre these days. I prefer to watch them at home on my big screen TV, perhaps with a friend or two coming over to share the experience and talk about what the movies mean to us.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) The other two were:

Indian Romeo and Juliet. Vitagraph

Chief of a hostile tribe enters enemies country and makes overtures of peace. He meets the daughter of the chief and they fall in love and are secretly married. The next day her father tells her she is to be married to one of her own tribe. She goes to the medicine man who is in the secret and favourably inclined towards her, and he gives her a sleeping draught, so that she will appear to be dead. She is taken to the burial ground and there her husband finds her and mourns over her not knowing that she is only asleep. The rival Indian comes along and they fight with knives when the husband kills the rival. He then kills himself with his knife and falls across the body of the girl, who awakened by the shock and finding her husband dead, also commits suicide.

Objections

Indians insufficiently dressed, use of knife and two suicides.

Marriage or Death. Pathe

A family of settlers are visited by a Morman who is desirous of marrying the daughter, who is engaged to another settler. He is refused and goes away. The settlers are warned by a friend that the Mormans are angered at her refusal and are determined to take the girl by force. The Mormans obtain the aid of a tribe of Indians, and they at once make for the settlers home, who in the meantime have left as a result of the warning. A chase ensues in which some of the settlers are killed and the girl captured and taken to the Morman settlement, where she is shown a knife and told that she will either marry the Morman or have her throat cut. She refuses and just as the knife is being raised to kill her a band of settlers, who have been collected by the girls lover, arrive and shoot the Mormans and rescue the girl.

Objections

White men getting Indians to help against white men. Abducting a girl. Using a knife to suggest cutting throat. Raising the knife to kill girl. (return)

Comments

Well done.

Thanks, Grant.

It did go well, though I don’t think I’m ready to take up a career in public speaking!

Very good, but what about the Oak theatre? (Logan and Main)

I actually have two paragraphs in there about the Oak – and the apparently well-known urban legend that if you brought your own apple box to sit on you’d get in for half-price.

My husband recently stumbled upon what appears to be signage for a Hollywood Theatre. Not sure if they came from a local theatre. But there was also some old posters suggesting that this was perhaps in operation in the 40s.

I can’t find any record of a Winnipeg theatre named the Hollywood. Where was the material found? I hope the posters were in good condition!

It was found in the basement of a hotel in the north east of the city (East Kildonan? Sorry I’m not a local, still learning the neighbourhoods) Current owners did not put it there.

That theatre might be the Roxy on Henderson Highway. There was a large hotel, the Curtis, fairly close by.

The other possibility was the Elm on Talbot at Allen. The Elm was my local during 1946-54. Memories!

It was managed by Sid Brownstone. But there were no large hotels nearby.

It was eventually torn down and replaced by a low-rise apartment block.

Thé theater probably was the Roxy on Henderson Highway. The hotel probably was the Curtis which was further up the road.

And yes, posters are gorgeous. All in really good condition.

Beautiful piece! So much rang a bell with me. Especially the sense of a completely different reality Experienced in a neighborhood movie house, and the shock when reemerging into the bright summer sunshine, which often gave me a headache after sitting six hours in the dark. My first experience was the Tower Theatre on Mountain and McGregor; later when we moved it was the deluxe on Main and Carruthers. Or we go to the college theatre with our cousins who lived a bit further south. And of course we all knew the legend about the Oak Theatre. if we wanted to see a really good movie that left our own theatre, we could always look in the papers to find another theatre which had picked it up.

Thank you for this trip down memory lane! Loved those old musicals with Gene Kelly. Also Bogart and Fred Astaire and Judy Garland. Still watch them on Turner Classic Movies.

Anyone know the names of 1950s cinemas on Pembina Highway north and south of McGillivary Boulevard?

Hi, the only ones in that area I’m aware of were the Garry, which was a bit further north on Pembina at Point Road, and the Pembina Drive-In, which was close to Bishop Grandin.

Bob Callaghan’s website – http://www.dancebob.com/Winnipeg_Theatres/Winnipeg_Theatres.html – is one of the most thorough records of Winnipeg theatres I know of and even he doesn’t list any others in that area.

The Delta Hotel had a theatre(old name North Star on Portage ave) The theatre is still there Under ground but not accessible to the General public

Yes, it had two screens. I saw many movies there.

Thank you for this. I fondly recall the North Star, as my family went there many times in 1981 to see “Raiders of the Lost Ark” more than 20 times. I can still see the orange-and-brown curtains from that theatre.

I’m trying to recall the name of the theatre that was on Portage at Vaughan, across from the old Hudson’s Bay building. It had a large long marquee along Portage, big enough to accommodate the full title of “The World According to Garp” in 1982. Do you know the name of this theatre-that-was?

That was the Colony, originally called the Gaiety, and for a time in the ’70s the Eve, which was an “adult” theatre.

My sister and I were just talking about the Tower Theatre at Mountain and McGregor. We lived pretty much kiddy-corner to it. She is 8 years older than I am and remembers an adjoining soda fountain with beautiful wood fixtures.

It was sadly replaced by a parking lot for the new Safeway built behind it. Would have been a beautiful building today to have kept. I vaguely recall white stucco and an art deco style.

We sorely wish someone had photos of it.

This is the only photo I know of, given to me by Sheila Streifler whose father built the theatre in 1937.