The joy of B: Sam Katzman’s 1950s horrors

One of the drawbacks of being an obsessive collector is the on-going accumulation of more movies than I could possibly have time to watch. Even if I stopped accumulating them right now, I’d be dead before I managed to get around to every movie I possess. It’s undoubtedly a sickness, but – I like to think – a relatively harmless one. A friend of mine recently moved and he told me that in preparation he got rid of a lot of his own movies. I asked how he made the necessary decisions and he said he just ditched anything he knew he’d never want to watch again.

That sounds simple and logical. But for me, it’s complicated by the fact that even if I think I won’t want to watch a particular movie again, I like having it as part of my broad and eclectic collection. There’s probably way too much self-image tied up in owning all these shiny disks, but at this point I can’t really see making the effort to cure myself.

Leading up to my own move last week, with so much of my stuff already packed away in boxes and feeling somewhat exhausted by the effort involved in preparing for a radical change after more than sixteen years in the same place, I came across something I’d forgotten I had – the Sony two-disk Icons of Horror Collection: Sam Katzman DVD set a friend had sent me years ago, and which I’d never gotten around to watching. Too tired to face anything more challenging, I spent the last couple of evenings in my old place watching these four B-movies from the ’50s, only one of which I’d previously seen (on television way back in the ’70s).

As I’ve mentioned here before, I have a long-standing affection for cheesy genre films – not in the mocking way that encourages a sense of superiority like, say, Mystery Science Theater 3000, but rather in recognition of the strange quirks of imagination mixed with crass commercial intentions. These movies generally exist solely because someone wanted to spend as little as possible in order to make back some paltry profit. That aim, so often rooted in cliches and blatant imitation, can on occasion produce something strange and unexpected, even if just for a few odd moments scattered through generally brief running times.

(I don’t include here genuinely original work produced in similarly impoverished circumstances – movies like John Parker’s Dementia/Daughter of Horror or Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide, for example.)

Sam Katzman started working in movies as an adolescent in the early teens, eventually working his way up to producer at various poverty row companies including Monogram – serials, westerns and jungle pictures – before landing at Columbia in 1945. There in the ’50s he produced a lot of rock’n’roll movies, including Rock Around the Clock (1956), directed by Fred F. Sears, whose next feature (also produced by Katzman) was Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), the best of the early Ray Harryhausen science fiction movies. Two of the movies in the Icons set were also directed by Sears. The other two were directed by the incredibly prolific Edward L. Cahn, the quintessential B-movie director.

The four movies in the set were all made between 1955 and 1957, along with sixteen more Katzman productions during the same period. None, by even the most generous judgement, can be counted art, but all are entertaining in their unambitious way and a couple even manage to rise above their required status as programme filler.

Both the Cahn movies feature zombies, though of very different types. Creature With the Atom Brain (1955) adheres closely to the mad-scientist/magical-properties-of-radiation tropes which date back at least to Lambert Hillyer’s Karloff and Lugosi-starring The Invisible Ray (1936). Angry gangster Frank Buchanan (Michael Granger) has somehow managed to hook up with Nazi scientist Wilhelm Steigg (Gregory Gaye), who has developed a technique to reanimate corpses with radiation, creating super-human slaves which Buchanan can control by radio. These zombies are sent to exact revenge on the gangster’s enemies, while police surgeon Dr. Chet Walker (genre stalwart Richard Denning just a year after co-starring in the classic Creature From the Black Lagoon) has to figure out what’s going on.

The most interesting element in the movie is the fact that Steigg and Buchanan, despite their protective gear, are being poisoned by the radiation they use to carry out their plans. Cahn revisited the same basic concept with Invisible Invaders in 1959, although in that the dead are reanimated by aliens, as in Edward D. Wood Jr’s Plan 9 From Outer Space (also 1959), an intriguing case of poverty row cross-fertilization perhaps. But perhaps the biggest legacy of Creature With the Atom Brain is the fact that it inspired the song of the same name by Roky Erickson and the Aliens.

The mix of poverty row noir and mad scientist in Creature gives it a kind of movie plausibility at the most basic level; the Cahn-directed Zombies of Mora Tau (1957) suffers in this regard. Ostensibly set somewhere in Africa, the budget is insufficient to muster up even the most rudimentary approximation of exoticism. Shot on backlanes and in woods around Santa Anita in California, it completely fails to establish a sense of location and has to rely entirely on its story, which is pretty half-baked.

Jan Peters (Autumn Russell) is returning to her family home in Mora Tau, presided over by crusty matriarch Grandmother Peters (Marjorie Eaton). Accompanying her are a seedy bunch of treasure hunters led by George Harrison (Joel Ashley) and diver Jeff Clark (Gregg Palmer); Harrison’s wife Mona is played by Allison Hayes in all-out sultry bitch mode. Despite Grandma’s warnings about the curse which overshadows the legendary treasure (looted from a native temple long ago by a ship’s crew headed by her own husband), the group bicker and argue and scavenge around, their efforts awakening the dead ship’s crew who have guarded the jewels for decades.

There are several amusing moments in an otherwise rather dull movie, including Grandma showing them all past a row of graves marking all the dead from previous treasure-hunting expeditions, ending with several freshly dug holes all ready and waiting for the new visitors, and particularly the way nobody seems to notice when Mona dies and is reanimated as a zombie. But overall Zombies of Mora Tau is the least interesting movie in the set.

The best movie included is Fred Sears’ The Werewolf (1956), the one I saw on TV years ago. It benefits greatly from being shot on locations around Big Bear Lake and the San Bernardino National Forest, but also from a script (by James B. Gordon and Robert E. Kent) which makes an attempt to treat its story with a degree of seriousness. With a pivotal character suffering from amnesia and tormented by uncontrollable urges, it has links to film noir, with the setting in a small mountain town raising echoes of movies like High Sierra and On Dangerous Ground.

The amnesiac Duncan Marsh (Steven Ritch) finds himself in the small town without knowing how he got there, but with vague memories of an accident and a doctor treating him. His arrival in town coincides with some violent attacks which appear to be the work of a savage animal. As local cop Sheriff Jack Haines (Don Megowan) investigates, Marsh’s wife Helen (Eleanore Tanin) and son show up looking for him and a sinister pair of doctors arrive. While Haines and Helen search for the missing Marsh, who’s hiding out in the woods, the doctors (Ken Christy and S. John Launer) seek to destroy the fugitive before anyone can find out that, when he had his accident, they used him as an opportune test subject which resulted in transforming him into a werewolf.

As is typical in this kind of story, the deeper motives of the doctors are unclear (how is their serum supposed to help mankind?); but the film presents them as villains while maintaining sympathy for their victim, even though he’s become an unwitting killer. When order is restored at the end by the expected elimination of the beast, that sympathy gives Marsh’s death a touch of tragedy.

The final film in the set, Sears’ The Giant Claw (1957), on the other hand, quickly descends into the realm of inadvertent comedy. This is one of those instances where the audience can only look on baffled, wondering just what the heck everyone involved thought they were doing.

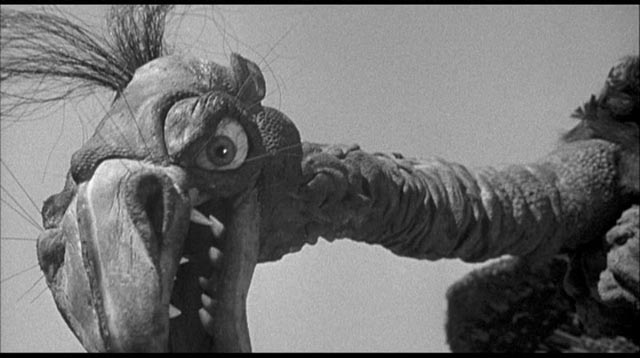

Structurally, the movie is a typical ’50s monster outing. Something is attacking planes, causing crashes while not showing up on radar. It’s up to aeronautical engineer Mitch MacAfee (Jeff Morrow – This Island Earth, Kronos) to figure out what the menace is. Well, what it is is perhaps the most ludicrously endearing monster of the decade. The “giant claw” is like a maniacal flying Muppet; its design is so distinctly mad that it can’t be termed shoddy … it’s a perfectly formed parody of giant monsters, an absurdist commentary on the likes of Rodan. (It also suggests a precursor to The Dark Crystal’s Skeksis.) Its presence overshadows the routine activity of the plot and transforms the movie into something almost deliriously charming.

Apparently Katzman had originally intended to have Ray Harryhausen create the creature, but the budget wouldn’t stretch that far so he farmed the work out to a company in Mexico City. It’s interesting to imagine the reaction of everyone who worked on the movie when they finally got to see it, their dutifully serious performances suddenly undermined and turned into unwitting parody by being cast against this bizarre puppet. While the rest of the movie belongs to the world of Bert I. Gordon’s Beginning of the End (also 1957), the monster here belongs to the wildest dreams of Ed Wood and what he might have done if he’d just had a little more money.

I’m not sure why it took me so long to get around to watching Icons of Horror Collection: Sam Katzman, but it turned out to be the ideal distraction in the midst of my moving upheaval.

Comments

Your assessment of The Giant Claw is inspired. I so enjoyed reading it. I’ve always marveled that that movie was made, let alone released. And I find it significant that the Henson crowd were behind both the Muppets and Dark Crystal (might they have an unseen hand in The Giant Claw?).