Recent disks from England: Arrow Video, part one

Arrow Video in England has quickly grown into one of the best disk distributors on either side of the Atlantic, with releases which are now comparable to the BFI and Criterion (though the choice of titles is frequently not as “respectable” as those released by these premiere distributors). Arrow has focused on genre movies, but have also added works by artists like De Sica and Elio Petri to their line-up. Like Criterion and the BFI, Arrow supplement their releases with often substantial special features – commentaries, interviews, documentaries and additional films (De Sica’s Miracle In Milan is accompanied by the director’s 1956 feature Il Tetto, for instance).

Upcoming genre titles include David Cronenberg’s Shivers (aka They Came From Within), Thom Eberhardt’s sci-fi/horror/comedy Night of the Comet, Fernando De Leo’s poliziotteschi Milano Calibro 9, a 5-disk set of Meiko Kaji’s Stray Cat Rock action movies. There are also editions of Jules Dassin’s Brute Force, Petri’s debut feature L’Assassino, Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels and a massive box set of the work of the transgressive Polish director Walerian Borowczyk. Here, I’ll talk briefly about a handful recent Arrow releases which have provided me with hours of worthwhile viewing.

The Killers (1964)

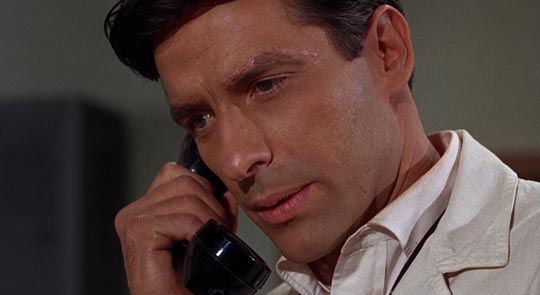

Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964) was given a previous home video release by Criterion as part of a fascinating 2-disk DVD set which was built around Robert Siodmak’s 1946 adaptation of Hemingway’s short story and included, perhaps the most interesting thing about the set, a student film version co-directed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1956. Like the Criterion edition, Arrow offers Siegel’s film in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, but also supplies a version in the 1.85:1 ratio in which the film was initially seen in theatres (Siegel and director of photography Richard L. Rawlings had framed the film to accommodate both). The reason for this variation lies in the movie’s origins as the first made-for-television feature, an idea cooked up by the head of Universal Studios Lew Wasserman, who saw the potential for profit in such projects as an alternative to re-selling theatrical features to TV after they’d exhausted their big screen potential.

As it turned out, for a number of reasons The Killers ended up not being broadcast and was first seen in theatres overseas before getting a theatrical run in the States. One fact was the level of violence in the film (not particularly graphic by today’s standards, but still quite nasty in tone). Perhaps more significant was the question of timing, with the film being completed around the time of the Kennedy assassination. This latter aspect provides what amounts to a bizarre, almost surreal shock late in the film. Villain Jack Browning (played by none other than Ronald Reagan in his final performance before taking on his long-running role as a depressingly influential politician) fires on protagonists Charlie Strom (Lee Marvin) and Lee (Clu Gulager) with a rifle from high in a building across the street, killing Lee and fatally wounding Charlie. The image of Reagan assassinating these men has disturbing visual echoes of what happened in Dallas and made the film essentially impossible to broadcast at the time.

The film’s dual narrative (scripted by Gene L. Coon, one of the most important contributors to the original Star Trek [1966-68]) begins with two hitmen carrying out a contract in a school for the blind. Lee and Charlie are immediately established as ruthless professionals with a casual streak of cruelty. And yet Charlie is troubled by the fact that the target, Johnny North (John Cassavetes), doesn’t attempt to run, doesn’t even flinch, just stands there and accepts his violent fate. This sets the team on a search to uncover what was behind the hit – which, as Lee points out, violates their code about not getting personally involved or showing any curiosity about their jobs. As Charlie and Lee cross the country to question various people connected with Johnny North, the secondary narrative plays out in a series of flashbacks in which we see Johnny, a prominent race car driver, falling under the spell of Sheila Farr (Angie Dickinson at her most seductive), who happens to be the “property” of criminal Jack Browning.

Johnny gets drawn into a robbery which needs his driving skills, but an inevitable series of double- and triple-crosses leave Johnny shattered when he realizes that the woman he loves has just been using him, setting him up as the fall guy so that she and Browning can cheat the rest of the gang and keep all the money for themselves. Their plan would have succeeded if Browning hadn’t put out the contract and set Charlie’s curiosity in motion. In the end, no one gets out alive and the movie ends on a brutally cynical note.

Arrow’s Blu-ray offers a bright, saturated image, which looks good in both aspect ratios. The extras include lengthy interviews with Marc Elliot, who talks about Reagan’s Hollywood career and how it played into his later political career, as well as the president-to-be’s distaste for the project (it was the first time he’d played a villain and he was concerned about the effect that would have on his public image should he choose – as he soon did – to run for public office); and Dwayne Epstein, who talks about Lee Marvin and the actor’s relationship with violence in his movies (which Epstein relates in part to Marvin having suffered from PTSD due to his experiences in the Pacific in World War Two). There’s also a brief, somewhat self-deprecating interview with Siegel from the French TV series Cinema Cinemas.

*

Pit Stop (1969)

Ace exploitation director Jack Hill started out doing patch-ups and additional shooting on various low-budget projects before somehow managing to get financing for his unique, perverse, and now cult favourite Spider Baby or The Maddest Story Ever Told. That tale of the degenerate Merrye family and their attentive caretaker Bruno (Lon Chaney Jr, who not only gave one of his best performances here near the end of his career, but also sang the catchy theme song) was too peculiar for distributors when it was made in 1964 and remained unreleased for years, only gaining a reputation years later thanks to mention in the 1986 Re/Search volume Incredibly Strange Films (which also happened to be the first place I encountered any mention of John Parker’s strange no-budget masterpiece Daughter of Horror/Dementia) and a belated appearance on home video. Given the fix-up work Hill had done on a number of movies (including a pair of Mexican-made cheapies featuring Boris Karloff at the end of his career), Roger Corman offered Hill an opportunity to write and direct a feature. Corman wanted a stock car racing story; Hill wanted to do an “art film”. Corman said go ahead, as long as there were a lot of crashes and Hill didn’t follow through with the idea of having the hero lose the big race.

Although Hill personally had no interest whatever in car racing, Pit Stop (on-screen title The Winner) exhibits an outsider’s fascination with a sub-culture defined by its ego-driven pursuit of danger. Dick Davalos plays Rick Bowman, a delinquent with a massive (unexplained) chip on his shoulder, who attracts the attention of race promoter Grant Willard (Brian Donlevy) at a reckless impromptu drag race on a city street. Bailing Rick out, Willard offers him a chance to race “legitimately”. Key to the film’s success was Hill’s discovery of figure-eight racing, in which the track has an intersection and the attraction for the fans is the endless string of crashes – basically, the last car running is the winner. Rick thinks it’s insane, but when taunted by Willard’s star driver, the crazy Hawk Sidney (Sid Haig), he agrees to try it.

And so the set-up seems pretty standard: newcomer underdog taking on the champ, and into the bargain taking the champ’s girl, Jolene (Beverly Washburn). But despite Corman’s admonition, Hill’s narrative trajectory doesn’t exactly lead where the audience expects. There’s something pathological about Rick’s ambition, which leads him to increasingly dangerous actions, both on and off the track. He wants to take Hawk’s place as back-up driver for stock car champ Ed McLeod (George Washburn), but he also takes aim at McLeod’s wife (Ellen Burstyn in an early role). By the end, he’s hurt two women, caused a death, and by his actions made Hawk become the more reasonable and responsible man. As Hill puts it, he might have won the big race, but he loses his soul.

Shot in black and white because in 1969 colour stock wasn’t fast enough for all the night scenes (colour would have required massively expensive lighting set-ups), the film has an on-the-fly documentary-like approach to the action – shot with five cameras over several nights of racing – and that action is pretty jaw-dropping. I may have been in just the right frame of mind to watch this paean to the bond between male egos and cars, expressed through aggressive displays of destruction, because I’ve been working for the past few months on a documentary about people who have made a conscious choice not to drive and are searching for ways to transform our dependence on automobiles and change the ways we construct our cities around traffic. Pit Stop is an excellent depiction of the underlying madness of our relationship with these more-than-potentially-deadly machines. It’s also very well crafted, with a more serious tone than the average car culture movie of the ’50s and ’60s.

Arrow’s disk supplies a gorgeous black-and-white image – probably looking better than any drive-in print at the time of its original release. The supplements include a commentary from director Hill; an interview featurette with Hill about the production; an interview with B-movie perennial Sid Haig; and an interview with producer Roger Corman; as well as a demonstration of the complicated restoration process explained by technical supervisor James White.

*

Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

It turns out I jumped the gun a bit when I ordered Arrow’s Phantom of the Paradise Blu-ray. Shout! Factory has announced their own region A release for August 5, which contains most of the extras from the Arrow edition plus a whole slew of additional special features exclusive to Shout. Which is not to say that Arrow’s release isn’t quite substantial, with two-and-half-hours of interesting contextual material, although as various on-line sites have commented Arrow’s image is problematic, at times rather dark and murky, which is not usually the case with their transfers. However, the audio is fine, which is obviously one of the key considerations with this film.

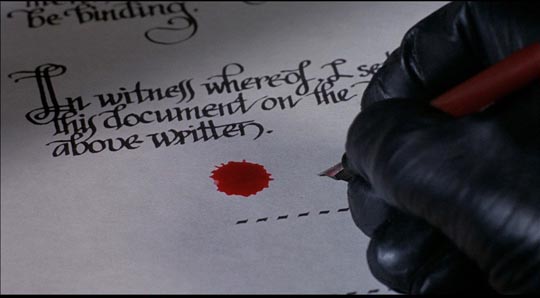

Although I saw Phantom of the Paradise on, I believe, January 10, 1975, a couple of weeks into its 18-week run at the Garrick Theatre in Winnipeg (I was flying to England later that evening and luckily my plane left just before a blizzard closed down the airport), I can’t say that I shared this city’s legendary obsession with Brian De Palma’s horror-comedy-rock musical. It seemed to me at the time to be little more than an amusing pastiche/homage to Phantom of the Opera, but I will confess to my immediate attraction to Jessica Harper, which was re-confirmed two years later by Dario Argento’s Suspiria. Having previously only seen De Palma’s Sisters (1973), I had no particular opinion of the filmmaker, but I definitely liked Paul Williams’ music, which seemed to be the film’s chief attraction.

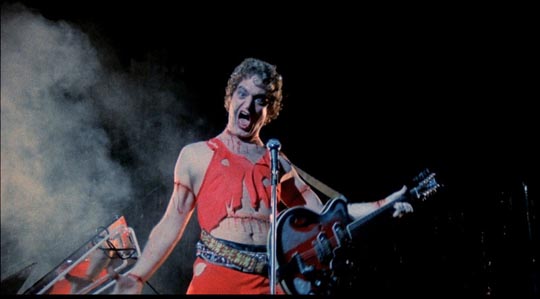

I’ve seen it a number of times since, and wore out my vinyl copy of the soundtrack long before the advent of CDs. In fact, even watching it now on Blu-ray, I couldn’t resist singing along (good thing I was watching it by myself); but I’ve come to appreciate De Palma’s craft, the surprisingly agile balance among the film’s multiple tones – key here are the performances of William Finley as Winslow/The Phantom and Paul Williams as Swan, the impresario who sold his soul to the Devil for eternal youth. Given the mix of comedy and genuine psychological torment, Finley manages to evoke real emotional depth in his hapless character. As Paul Williams points out in one of the disk’s extras, it’s remarkable how much expression Finley can get from a single eye staring out of the Phantom’s mask.

Although the film’s themes are not particularly original – the conflict between art and commerce, the price people are willing to pay for fame, and so on – De Palma expresses them with infectious energy and the film has an exhilarating sense of creative freedom which too often devolved into (often derivative) cleverness in his later work. It takes skill to simultaneously send up his material and instill it with genuine emotional power and it seems clear that to a high degree his accomplishment here rests on the strong support of Williams’ music, which like the film combines parody and pastiche with genuine emotion. And, of course, there’s an excellent cast to carry the story, with Finley, Williams and Harper well supported by George Memmoli as the scuzzy agent Philbin and, particularly, Gerrit Graham as Beef, whose pre-death performance of Life At Last is one of the film’s high points.

The 50-minute documentary Paradise Regained does a good job of illuminating what makes the film so distinctive, and explaining why it was not initially a success except in Winnipeg, Paris and Japan. It also details some of the interesting difficulties De Palma faced in completing it, particularly the last-minute necessity to optically replace all on-screen instances of the Swan Song logo after Atlantic registered a subsidiary named Swan Song Records (this aspect gets its own 10-minute video featurette); I must admit that I’d never noticed all the instances of unstable Death Records logos throughout the film which had been optically pasted over existing shots – but once pointed out, they’re rather obvious. More damaging, however, was the re-editing forced on De Palma where such replacement wasn’t possible, altering the rhythm of some sequences and eliminating a visual theme running through the film which emphasized just how ubiquitous Swan’s power is in the film’s narrative world.

Apart from the documentary, the disk’s most substantial extra is a 72-minute conversation between Williams and Guillermo Del Toro, who turns out to be a huge fan of the film and of Williams’ music. It’s a relaxed, discursive and ultimately quite illuminating discussion about creative process and fandom.

Next: Arrow’s edition of Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye (1987).

Comments