More Recent Viewing

Someone recently posted a comment on one of my reviews for Blogcritics, calling me stupid for not “getting” a movie he’d obviously been obsessing over for a long time. Sometimes, of course, one doesn’t completely understand a movie the first time one sees it (I never could understand Pauline Kael’s assertion that she only needed to see a movie once and didn’t think she’d get anything else out of it by looking again). So I’m certainly willing to entertain the idea that I missed something in that particular movie. And maybe I missed something when I finally sat down to watch Steven Spielberg’s War Horse the other day.

War Horse (Steven Spielberg, 2011)

There is of course no question about Spielberg’s ability to create images and build scenes … but at almost two-and-a-half hours, I found myself wondering constantly just what it was he was trying to say. The film starts with a long opening section dealing with a poor farming family in the west of England, a hard-working mother (Emily Watson), a tormented alcoholic father (Peter Mullan), and their son Albert (Jeremy Irvine). Faced with debts to their landlord Lyons (David Thewlis), dad makes things worse by spending every penny they have on a horse at auction … not the draft horse they desperately need to plough their rocky patch of ground, but a beautiful thoroughbred.

Albert falls in love with the horse, which he names Joey, and works hard to train it, eventually – in one of those rousing old-style movie scenes – actually getting it to pull the plough in a rain storm with all the neighbours and Lyons and his men looking on. It’s Rocky going the distance in the ring against all the odds, it’s the plucky ingenue going on and saving the show and the backer’s investment on Broadway, it’s the Wright Brothers finally getting their fragile plane off the ground … in other words, a moment of pure movie triumph.

But the family is still broke and when the First World War breaks out, dad sells Joey to the army. There’s a heartbroken farewell as the horse is led away and the movie sets off on an episodic journey through four years of war. He’s lost in a futile cavalry charge against machine guns, taken by the Germans; he finds his way to a girl with some undisclosed health problem and her grandfather; he’s captured again and forced to pull heavy guns up steep hills; he makes a break across No Man’s Land and gets tangled in wire, his desperate situation bringing a momentary truce as one soldier from each side goes out to cut him free … by now, the war is almost over, Joey has finally reached his physical limits and a brusque officer orders that he be put out of his misery. But just then, Albert, walking wounded and blinded by mustard gas, finally meets up with his beloved companion. Joey is spared and after a few more traumas, the pair make it back to the farm …

War Horse is packed with sweeping vistas, grand-scale scenes … but what is it about? Is Spielberg trying for his own Au Hasard Balthazar, attempting to illuminate the dark side of human nature by looking at the world through the eyes of an animal at the mercy of our species? But Joey constantly meets people who show their best side in his presence, caring officers and soldiers and civilians on both sides of the conflict who are all almost mystically drawn to the animal as the world goes to hell around them. The fetishization of the horse and the lush, colourful images have the bizarre effect of draining the horror out of the war, cleansing the appalling suffering of millions of men who lived in filth and squalor and interminable fear and pain for four long years so that we can feel a sentimental frisson when boy and horse find each other again.

Despite the historical background, War Horse has no more weight than Lassie Come Home, and Spielberg’s final overwrought homage to John Ford, with Albert and Joey’s return to the farm supposedly achieving the kind of mythic closure of The Searchers, is picturesque in the worst, anti-dramatic way possible. There was a degree of sentimentality in Saving Private Ryan, but here that tendency in Spielberg overwhelms the film and the beauty of the images becomes nauseating because they falsify everything the movie pretends to be dealing with.

The Point (Fred Wolf, 1971)

But then, of course, I may simply have missed the point. Something which would be impossible with Harry Nilsson and Fred Wolf’s The Point, a charming animated children’s fable set to Nilsson’s catchy music, originally made for television in 1971. The message here is simple and clearly stated, but the wit of the script and the nuances of the storybook-style animation enrich the message of difference and acceptance.

In the land of Point, everything, as the lyric says, “has one.” All the people have pointed heads … until the birth of Oblio, a bright and personable little boy with a round head. No one much cares and his mother makes him a pointed hat to help him fit in. But the mean-spirited son of the Count resents the fact that Oblio, with the help of his pointy dog Arrow, can beat him at the popular game of triangle toss. So the Count forces the King to apply the law, which insists that without a point, Oblio must be banished to the Pointless Forest.

So the cheerful Oblio and Arrow set off on the road for a series of encounters – with the Pointed Man, the Rock Man, some mean bees – and eventually learns that since everything that exists has a point of its own he must have one too. He returns home in triumph, and the Count slinks away in humiliation.

Although a few sequences now seem too much of their time (with a bit of Yellow Submarine‘s psychedelic influence), the simplicity of Wolf’s hand-drawn images (the director drew the entire film himself) and the warmth of Nilsson’s catchy songs – “Me and My Arrow”, “Think About Your Troubles”, “Are You Sleeping?” and so on – enrich the simple message in the way that great folk tales can seem profound beneath their simple narrative surface.

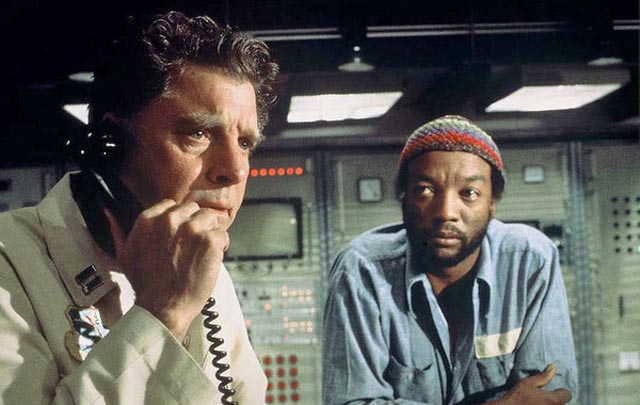

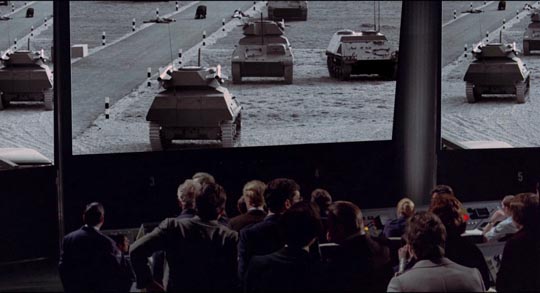

Twilight’s Last Gleaming (Robert Aldrich, 1977)

It’s a sad coincidence that so soon after the release of Robert Aldrich’s Twilight’s Last Gleaming on home video, Charles Durning, who plays President Stevens in the film, has died. Durning was a great character actor, a stocky, almost nondescript man, who was capable of sliding into a role and inhabiting it, often as a villain (like his hissable redneck Otis P. Hazelrigg is Frank De Felitta’s Dark Night of the Scarecrow [1981]). But one of his finest roles was in Aldrich’s thriller – in fact, he gets the very best scene in the movie, facing a critical moral decision in a two-way confrontation with Gerald S. O’Loughlin’s General O’Rourke.

I must admit that when I saw Twilight’s Last Gleaming on its first release in 1977, I didn’t think much of it. Aldrich’s best work seemed long behind him (a string of harsh, cynical movies in the ’50s, which had been displaced by big commercial projects in the later ’60s and ’70s), and at the time the use of split screen seemed like a tired, outdated gimmick. But there were also conceptual issues, some of which, even on a more favourable re-viewing today, are problematic.

A discredited general (Burt Lancaster) escapes from prison with several death row inmates and manages to infiltrate a nuclear missile base in the mid-west. With his knowledge of the weapons system, General Dell is able to dismantle all the fail-safe mechanisms and isolate the silo from any outside command and control. He’s gained the help of his fellow cons by promising them a large sum of money, but his real demands are political. He wants the president to release a secret document which proves that the Vietnam war was a cynical exercise in realpolitik, designed to prove to the Russians that the U.S. was willing to behave with ferocious brutality and thus should not be messed with; that the destruction of so many Vietnamese and American lives had no practical aim, but was rather a deliberate gesture of pointless madness, an expression of total cynicism at the highest levels of power.

Of course, this was only a few years after Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to the press and exposed the falsity of the official reasons for the war. So what Dell is asking for hardly constitutes a new revelation. And the fact that he uses the threat of initiating a globe-destroying nuclear war to try to expose this hardly-secret information actually puts him in the category of dangerous fanatic. All of this struck me as highly problematic in 1977. But watching the film again on Blu-ray, I’ve revised that opinion somewhat.

Dell (Lancaster in one of his last great performances) is a madman, driven there by his sense of betrayal by the system he has served all his life. His anger at having been lied to blinds him to the real consequences of his current actions until near the end of the film. Although the effort to get the document released drives the plot, the film’s main aim is simply to expose the appalling self-interested cynicism of those in power. Like other ’70s thrillers (Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men …), Twilight’s Last Gleaming is essentially a gesture of disgust at what politics has come to in the U.S. The core of the film consists of the protracted discussions in the White House between the President and his advisers, all seemingly thoughtful, practical men for whom the protection of the status quo supersedes any moral principles. When the President’s own sense of morality is awoken by Dell’s actions, he becomes as expendable as the renegade general.

Meanwhile, the military which Dell sees as betrayed by the politicians is represented by the ruthless General Mackenzie (Richard Widmark), who will obey orders no matter how appalling they are. Aldrich’s measured direction makes Dell’s failure and the triumph of cynicism seem inevitable and the film ends on what may be the bleakest note of the decade. And seen now, the use of split screen seems much less a tired gimmick; it ties three separate narrative lines together, emphasizing simultaneity and cause and effect, and actually seems to accelerate the pace so that 140 minutes breeze by. Given that the film consists almost entirely of three separate groups having lengthy conversations in three separate rooms, it’s remarkable how much tension Aldrich is able to generate with this technique.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given that it was being made at the same time as Star Wars, George Lucas’s uncomplicated ode to righteous combat, Aldrich had to go to Germany to find financing and make the film. The Olive Films Blu-ray includes Robert Fischer’s excellent feature-length documentary about the production, Aldrich Over Munich (2012), which makes clear how personally committed the director was to the project.

Comments