Alan Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974): Criterion Blu-ray review

Thrillers have always traded in paranoia – it’s a key element of the genre, with initially unknown threats upending characters’ complacency about the stability of the world they inhabit. From the late 1940s into the early ’60s, the threat in American thrillers was usually external, with nefarious Commies trying to undermine the state – this reached its peak in 1962 with John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate. By the end of the ’60s, after a decade of protests and assassinations, war overseas and political corruption at home, there was no longer any belief in the state as a stable entity. Heading into the ’70s, as often as not the threat was coming from inside. Modern thrillers frequently hinge on rogue elements inside the government posing a threat to ordinary citizens; trust has vanished and no one seems surprised … so it may be difficult for a contemporary audience to fully understand the unsettling shock delivered by thrillers in the ’70s. Paranoia, rather than being a device adding a frisson to the suspense, became the essence of the narrative. Heroes were doomed never to triumph and uncertainty remained unresolved, leaving the audience in an uncomfortable state of anxiety.

The defining moment of this emerging ethos comes at the end of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974): “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.” Corruption is inevitable and there’s nothing anyone can do about it … gaining knowledge doesn’t instill power, it merely amplifies the hopelessness and breeds cynicism. This gloomy perspective permeates detective movies of the period – in addition to Chinatown, there’s Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975), Robert Culp’s Hickey & Boggs (1972), Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) – and cop movies like William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973), Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (also 1971).

Perhaps no one defined the new mood better than Alan J. Paula. A successful producer of prestigious dramas for more than ten years, Pakula began directing at the turn of the decade. While his first and third features are romances centred on teen characters, his second, fourth and fifth comprise a paranoid trilogy in which style and content are interwoven into a chilling depiction of a world in which individuals are trapped inside social and political machines controlled by unseen forces whose motives are barely discernible.

Beginning with Klute (1971), a character study and romance disguised as a detective story about the search for a serial killer, and ending with All the President’s Men (1976), an almost clinically cool dissection of Richard Nixon’s efforts to corrupt the mechanisms of American political power, the trilogy is anchored by The Parallax View (1974). “Style over substance” is a common pejorative for movies which seem to put more emphasis on visuals than narrative, but in the case of a film like The Parallax View style is substance. Working for the second time with masterful cinematographer Gordon Willis, Pakula uses the extremely wide frame (2.39:1) to create a world of modernist architectural spaces antithetical to human life; characters frequently exist as small figures almost lost in vast geometrical configurations, forcing the viewer to search for them and intuit relationships which remain ill-defined. This is a cold world where menace is as likely to lurk in a sunlit exterior as in a poorly lit, claustrophobic interior.

The opening sequence comprises multiple signifiers of American identity, rooted in myths about the past and fantasies of the future. The first shot, over which we can hear a marching band, is of a native American totem pole which bisects the frame; the camera tracks sideways to reveal the Seattle Space Needle which had been concealed, past and future now side by side, suggesting an idea of historical inevitability. This cuts to a parade with band and majorettes conflating ethnic signifiers (the majorettes appear to be Chinese, while their costumes are faux Native American), a politician riding high on a vintage firetruck with a fireman’s helmet on his head. The crowd cheers; a local TV reporter, Lee Carter (Paula Prentiss), gushes vacuously about the handsome, popular campaigner, and follows him into the Needle’s elevator, pointedly not helping scruffy reporter Joe Frady (Warren Beatty) get past security.

Up in the tower, in the midst of a crowded reception, the politician is shot by one of the waiters, who falls to his death as he tries to flee. However, we see something no one else does: a second waiter (Bill McKinney) tucks a pistol inside his jacket and slips away. Months later, a congressional committee announces its finding that the assassin was working alone. The echoes of the Warren Commission and other investigations couldn’t be more clear; the tidiness of a lone assassin is essential to maintain the status quo.

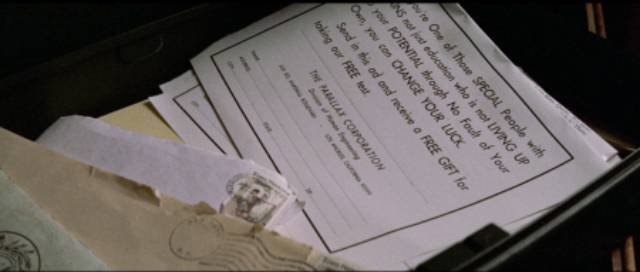

Three years later, Lee visits Frady in desperation – six of those closest to the assassination have died in “accidents” and she’s afraid she herself is a target. He doesn’t take her seriously; only the gullible believe in conspiracies. But then she too dies and he suddenly needs to dig into the story, even though his indulgent editor Bill Rintels (Hume Cronyn) refuses to believe anything untoward is happening. As he starts to investigate, he finds himself a target … and he stumbles on the Parallax Corporation, a high-tech security company whose recruiting tools appear to be designed to ferret out sociopaths for special assignments. Frady takes their test and, playing the role of a loner with a troubled past, he’s recruited.

As the narrative moves inexorably towards its dark climax, it gradually becomes apparent that as smart as Frady is (one of the film’s strengths is that he is smart) the system he’s being drawn into is even smarter. He thinks he’s on top of things, but it turns out he’s being manipulated – that in fact Frady himself, a bit of an outsider and troublemaker, is actually ideal material for the corporation’s purposes.

Perhaps one of the film’s most prescient ideas is that the details of politics are becoming irrelevant; corporate capitalism has supplanted ideology and this vast business which arranges assassinations to remake the electoral landscape has no particular interest in what its customers and targets believe. What matters is the money to be made along the way. (Although it’s never specified, visual cues suggest that the first target is Democrat, the last Republican.)

The imagery throughout is quite stunning, whether in the gloomy little room Frady takes when he goes undercover, the dam and rocky ravine where he discovers he’s become a target, or the Los Angeles convention centre where Frady finds himself trapped and doomed during the climactic assassination, with the frame split between the expansive floor below and the network of shadowy catwalks above. In an interview on the Criterion Blu-ray, Gordon Willis expresses his dislike of the sequence in a smalltown bar where Pakula stages a fight which evokes every Hollywood B-western ever made. The set is tacky, full of breakaway furniture, and it does risk breaking the film’s illusion of a coherent world – but it also echoes the ersatz history and self-serving myths evoked by the opening sequence, the fakeness of America’s view of itself in contrast with the chilling reality which people prefer not to acknowledge.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about The Parallax View is that, being made in the midst of a writers’ strike and undergoing radical changes during production, with many scenes concocted on the fly, it feels so tightly constructed and coherent. Perhaps if it had been made under more stable conditions more might have been explained and clarified, but the fact that the Parallax Corporation remains ominously vague and inaccessible adds another layer which strengthens the unease an audience experiences, making it the finest of all ’70s paranoid thrillers, which remains remarkably undated.

Actually, that last point is complicated, because modern thrillers tend to be so hyperactive and over-cut to within an inch of their lives, that it’s almost a shock to find how much narrative tension Pakula generates with his cool, almost detached formalism. There aren’t many close-ups in The Parallax View; even conversations tend to take place in the middle distance, with characters arranged in space at some distance from one another, and action plays out in extremely wide shots which are held far longer than any filmmaker today would risk. This technique permits what I can only refer to as a natural tension to develop, as opposed to the artificially constructed tension of rapid editing which creates a perpetual illusion of momentum. Pakula allows the viewer to see the world of the film clearly, and this clarity gives what we don’t know far more impact. Surely when we can see things so sharply, we should be able to understand – and yet we don’t because the forces driving events remain hidden behind the scenes.

There is also one particular sequence which must be almost incomprehensible to a modern audience. When Frady follows McKinney’s assassin to the airport and sees him deliver a piece of unaccompanied luggage to a baggage handler, Frady boards the plane and, after take-off, buys a ticket from the flight attendant before dropping a note on the drinks cart warning of a bomb on board. With most of the passengers smoking, the plane turns around and returns to Los Angeles before the bomb explodes. The laxness of security and airline protocols seems impossibly absurd in light of what travellers have come to deal with in the past few decades.

Beatty is excellent as Frady, infused with a self-confidence which edges towards arrogance, leading him to his own destruction. Cronyn has the most cliched role, but infuses it with his usual depth and humour, while Prentiss in just a couple of scenes lays the groundwork for the sense of danger which permeates the film. Other standouts in small but telling roles are William Daniels as another witness targeted by Parallax, Walter McGinn as the company recruiter and Bill McKinney as the assassin.

*

The disk

The 4K restoration from the original negative on Criterion’s Blu-ray really brings out the filmic textures of Gordon Willis’ cinematography, with dense shadows and sharply defined architectural spaces. The Parallax View represents the peak of Alan J. Pakula’s visual style and it’s great to have the film looking this good on disk.

The supplements

The extras begin with an enthusiastic introduction from Alex Cox (15:00), in which the filmmaker expresses his admiration for the movie and situates it within its genre. There are two brief interviews with Pakula, both recorded at the AFI (1974, 17:59; 1995, 5:55) in which he recounts the problems he faced making the film and the political climate out of which it arose. In a 2004 interview with Gordon Willis (18:17), the cinematographer talks about working with Pakula, issues arising from shooting without a finished script, and his reservations about the quality of some of his own work in the film. Pakula’s assistant on the film, Jon Boorstin, also speaks about the ad hoc nature of the production in a 2020 interview (14:56), in which he also talks in detail about concocting the written Parallax Corporation test and assembling the company’s recruiting film which Frady has to watch; this was an audacious element which we see in its entirety (about 3 1/2 minutes) without any cutaways to Frady watching – beginning with cliched, positive images of middle class family life, as the pace increases jarring juxtapositions multiply, introducing violence and anxiety as Frady’s responses are monitored.

The booklet includes an essay by critic Nathan Heller, plus an interview with Pakula from 1974.

Comments