More genre viewing – late Fall 2018: Part Two

Severin Films specializes in genre and exploitation movies from around the world, so their catalogue is an interesting mixed bag full of imaginative low-budget horror titles which more than occasionally dip into the disreputable. Three of the disks I’ve watched recently are films by Italian directors, one is Australian and the fifth Swedish. Two are overtly influenced by H.P. Lovecraft, one is an unconventional take on vampires, and one a grisly, derivative zombie movie made to cash in on the commercial success of Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979).

Zombi Holocaust/Doctor Butcher M.D.

(Marino Girolami, 1980)

Marino Girolami had already made seventy movies over a thirty-year career when he dove into the graphic blood-and-guts pool in his mid-60s. I don’t think I’ve seen any of his other movies, which, glancing at his filmography, look like the usual collection of comedies, westerns, thrillers and eroticism typical of a hard-working commercial Italian filmmaker. Possibly his most significant contribution to the national cinema was being the father of the higher-profile Enzo G. Castellari.

Although Zombi Holocaust (1980) is mostly a by-the-numbers effort, which at times draws so closely on Fulci’s film that it borders on plagiarism, Severin have lavished an embarrassing amount of attention on the movie. In addition to a quantity of extras sufficient to choke a zombie, there are two separate cuts presented on two Blu-ray disks. The package privileges the American exploitation version – the re-cut feature released by Terry Levene under the title Doctor Butcher M.D. is on disk one, along with a number of interviews and featurettes focused on grindhouse distribution and the changes made by the distributor – which include trimming a lot of scenes and adding a very ill-fitting prologue in order to get zombies in right away. This latter material was shot by Roy Frumkes for his contribution to an omnibus project called Tales That Will Tear Your Heart Out, which was never completed. Intended to spice up the movie’s opening, this stuff actually acts as a drag on the movie – it doesn’t match photographically, the zombie designs are completely different, and the pacing is lugubrious.

Like Fulci’s movie, Zombi Holocaust begins in New York City. Here, though, it isn’t the arrival of the zombie plague on a boat, but rather a series of horrific killings in a big hospital which initiate the action. Someone is cutting organs out of patients and eating them. Dr. Peter Chandler (Ian McCulloch, adding to the sense of Zombie deja vu) teams up with anthropologist Lori Ridgeway (Alexandra Delli Colli, who would turn up two years later in Fulci’s notorious The New York Ripper) whose childhood spent on a remote Pacific island immediately helps her identify the activities of a cannibal cult, leading to a hospital worker who’s enacting ritual killings and organ consumption.

Concerned about this primitive behaviour turning up in NYC, Chandler and Ridgeway head for the island. Not surprisingly, they encounter resistance and warnings, with Chandler’s old acquaintance Dr. Obrero (Donald O’Brien) deliberately directing them away from the island at the heart of the mystery. But a bit of engine trouble forces the party to anchor, by chance on the very island they were not supposed to reach. There, they encounter the mutilated, rotting ambulatory dead … who turn out to be the result of Obrero’s experiments. To add spice, there’s conflict between the zombies and the cannibal cult, the latter adopting Ridgeway as their queen.

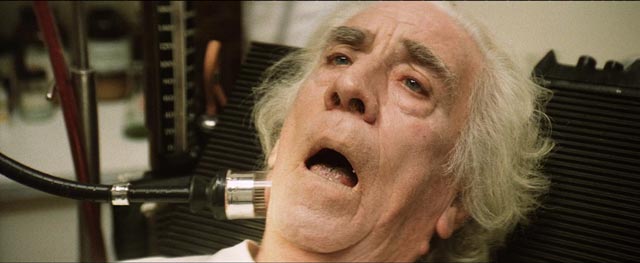

While Chandler is discovering the truth about Obrero and facing a brain transplant in a decidedly unhygienic shed (which looks identical to the clinic of Dr. Menard in Zombie), Ridgeway undergoes a ritual coronation, giving her the power and authority to lead the cannibals on a final assault against the zombie stronghold. This mish-mash of borrowed elements is occasionally entertaining, but Girolami lacks Fulci’s style and it all feels kind of perfunctory.

The second disk, featuring the Italian cut, has its own collection of extras focused on the original production. Severin also helpfully include a replica of the original Doctor Butcher M.D. promotional vomit bag.

*

Beyond the Darkness (Joe D’Amato, 1979)

Joe D’Amato (real name Aristide Massaccesi) was almost ridiculously prolific. He directed almost two-hundred movies in just under three decades, and photographed almost two-hundred more. I don’t know if we can attribute any significance to the fact that he signed his cinematographer credits with his real name far more frequently than his directorial work. As a director, he didn’t have a lot of finesse, often tipping over the edge from exploitation to porn. He liked to combine graphic sex with gore in movies like Emmauelle and the Last Cannibals and Porno Holocaust, but there isn’t a lot of atmosphere in the few movies of his that I’ve seen. Even when the gore is piled on, it has little impact.

For horror fans, he’s probably best known for Anthropophagous (1980), about a group of tourists stranded on a Greek island where they’re picked off by a deformed cannibal. It’s most famous for a climax in which the monster, having been cut open by the hero, proceeds to eat his own intestines. As I said, not very subtle!

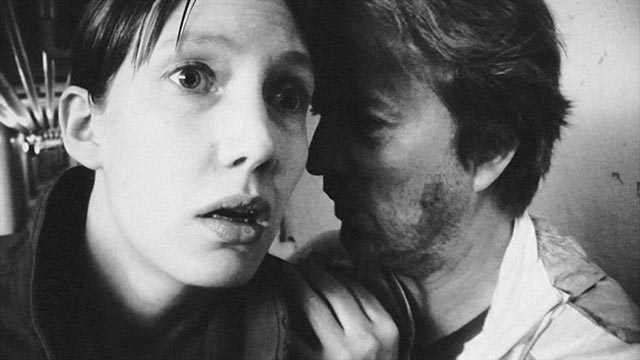

Much better is Beyond the Darkness (Buio Omega, 1979), a movie which surprised me with its relative restraint given the theme. Frank Wyler (Kieran Canter), stricken with grief by the death of his fiancee Anna (Cinzia Monreale, the blind psychic in Fulci’s The Beyond [1981]), digs her body up and uses his taxidermy techniques to preserve her. But given her unresponsiveness, he takes to kidnapping random women, taking them back to the country house he shares with Iris (Franka Stoppi), a perversely maternal woman who helps him dispose of his victims – and whom he isn’t aware had killed Anna with black magic in order to maintain her hold over him.

Although Iris helps Frank with some occasional sexual release, he can only find satisfaction by making love to a woman in the same bed where the stuffed corpse of Anna is tucked under the sheets. So it’s kind of necrophilia by proxy …

There’s a queasy power to the movie and the twisted psycho-sexual bond between Frank and Iris, but it’s most famous for the lengthy and disturbingly graphic sequence in which Frank practices his taxidermy skills on Anna’s body. Beyond the Darkness is unapologetic exploitation which revels in its own perversity, bolstered by a synth score by Goblin at their most Tangerine Dream-like.

Severin’s special edition includes interviews with D’Amato and actors Stoppi and Monreale, with a second audio disk of the complete Goblin score.

*

Dark Waters (Mariano Baino, 1994)

I don’t know much about Mariano Baino, other than that he’s Italian, that he apparently studied at the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia in Rome and eventually moved to England where he began making short films. His filmography is very sparse – just a handful of shorts made between 1989 and 2017, with a few scriptwriting credits on movies directed by other people. His sole feature, made in 1994, is a moody Lovecraftian piece shot under difficult circumstances in Ukraine.

Dark Waters is set in a convent on a remote island where it’s eventually revealed that the nuns are devoted to something more ancient than Christianity. Elizabeth (Louise Salter) travels to the island to investigate the mystery of her own origins – she was born there, her mother dying during labour, and although her father took her away to London, he has supported the convent financially ever since. He’s now dead and she wants to know what the family connection to the island is.

The sisters are not exactly welcoming and Elizabeth gradually discovers sinister goings on in a system of cellars and caves beneath the convent, rituals to honour and appease an ancient Lovecraftian deity who, perhaps not surprisingly, turns out to be Elizabeth’s true mother.

Despite its low budget, Dark Waters is atmospheric and at times visually striking – the candle-lit catacombs are impressive. Using the visual trappings of Catholicism, it presents religion as sinister and dangerous. There’s a quote attributed to Baino on IMDb which explains the film’s tone:

“Growing up in Naples, I used to be terrified by the Catholic iconography, by the array of very morbid and disturbing images which seem to fill so many churches in Mediterranean Countries. All those statues of people suffering, their agonized eyes staring down at me, Christ nailed to the cross, his mother’s bleeding, pierced heart. Deeply distressing stuff.”

Although not based on any specific Lovecraft story, Dark Waters captures the mood of the writer’s work as effectively as any direct adaptation – in fact, better than many that claim Lovecraft as their source.

Severin’s Blu-ray ports over all the extras from the No Shame DVD special edition – including the director’s commentary, several featurettes and four of Baino’s shorts – adding three new featurettes about his influences and the making of the film.

*

Thirst (Rod Hardy, 1979)

Made at the height of Ozploitation’s golden age, Rod Hardy’s Thirst (1979) is an imaginative variation on the vampire genre which seems prescient in its depiction of the 1% literally perpetuating itself by consuming the life essence of the 99%. An international cartel of privileged blood-drinking plutocrats has plans to turn the entire world into its feeding ground and a key element is enlisting Kate Davis (Chantal Contouri) who is unaware that she’s descended from Countess Elizabeth Bathory, the Hungarian noblewoman who used to bathe in virgin’s blood to maintain her youth.

Kate is kidnapped and taken to the group’s compound somewhere in Australia where she discovers that they’ve industrialized vampirism, developing blood farms where enslaved humans are systematically “milked” to provide the life-sustaining supply of plasma. Thematically, the film echoes the same year’s The Clonus Horror (directed by Robert S. Fiveson), in which the wealthy keep themselves alive by harvesting organs from their own clones who are kept ignorant of their purpose in a similar institutional setting. (Clonus was unofficially remade by Michael Bay as The Island in 2005.)

Thirst has a sharp script by John Pinkney and a strong cast, with David Hemmings as a key member of The Brotherhood who may have plans of his own. It’s certainly one of the most political of the Aussie horrors from that period; although its critique of an international Capitalist elite may not be terribly original, its use of literal bloodsucking as a metaphor for their self-serving behaviour is handled with some wit.

The Blu-ray includes a commentary from director Hardy and producer Antony I. Ginnane and an isolated audio track for Brian May’s score.

*

Feed the Light (Henrik Möller, 2014)

I ordered this after being interviewed by filmmaker Henrik Möller for his podcast Udda Ting several months ago. A prolific maker of experimental short films, Möller is steeped in genre literature and film (a glance at the list of his podcasts available on Soundcloud reveals an interest in the classic horror pulp writers like Lovecraft, Robert W. Chambers and Clark Ashton Smith, as well as filmmakers ranging from Dan O’Bannon, Brian Yuzna and Lucio Fulci to Werner Herzog and David Lynch).

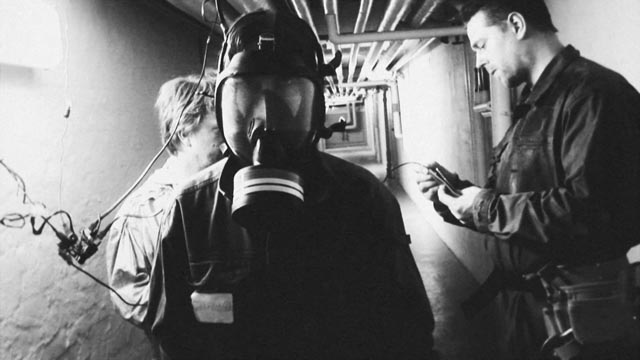

Feed the Light uses Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space as a jumping off point, but bears little resemblance to the source. In Lovecraft’s story (adapted a number of times, most recently as Die Farbe in 2015), a meteor crashes in remote New England and the radiation it produces gradually mutates everything it touches – plants, animals and people. In Möller’s film, the setting is a bleak industrial building in Malmö, Sweden, where something is distorting time and space and affecting the workers in strange ways. Our way into this facility is Sara Hansson (Lina Sundén), a desperate mother who has lost custody of her daughter Jenny (Ingrid Torstensson) to her abusive husband. This is quickly sketched in in an oblique prologue; somehow Sara knows that her husband has taken Jenny to the strange facility in an industrial part of the city. Sara sneaks in and immediately finds herself being interviewed for a cleaner position, which she gets.

Everyone she meets behaves in a slightly unnatural, and frequently threatening way – particularly the administrator (Jenny Lampa), who is aggressive during the interview, while a naked man crouches muttering under a blanket in the corner of the office. The foreman (Martin Jirhamn) is also aggressive, but realizes that Sara isn’t really a worker and eventually helps her to look for Jenny. Sara encounters her ex-husband (Patrik Karlson), who has strangely aged as he tries to document what’s happening in the building on video. He’s also lost Jenny somewhere in the lower levels.

The cleaning crew Sara is attached to has the job of continuously sweeping up glittering particles which accumulate beneath every light fixture – the light itself is menacing, this residue being a source of contamination and transformation. One worker gets covered with the glittering substance and it seems to drive him mad; the eyes of those infected become completely black, and perhaps the vague shadowy figures haunting the corridors are former workers who have been further transformed.

Möller skillfully uses very simple techniques to suggest the distortions of space in the building (as Sara sweeps a floor the head of her broom disappears as if passing into another dimension) and vaguely human-shaped shadows drift along corridors, seeming to swallow anyone they encounter. With the foreman’s help, Sara penetrates deeper into the building, following visions of Jenny which may or may not be illusions intended to trap her.

In a cave deep below ground, a containment device holds the alien power source; it supplies energy to the whole building, but that energy is contaminating space, distorting time and mutating the people who come into contact with it.

Shot on digital video, the film has the grainy high contrast look of 16mm black-and-white film (with occasional touches of colour suggesting the unhealthy atmosphere produced by the alien energy source). Feed the Light evokes cosmic horror with little more than an empty decaying building, a handful of characters, a few simple digital effects and an ominously creepy soundscape. By applying the techniques of experimental/underground cinema to genre material, Möller creates an unsettling world which avoids the usual pitfalls of low-budget fantasy – movies which either can’t afford to realize the ambitions of their makers or simply succumb to stale cliches. The film is surprising, at times disturbing, and also at times unexpectedly beautiful.

The Blu-ray (from Severin’s InterVison sub-label) brings out the subtlety of the imagery and the soundscape. There are two short featurettes – a brief making-of and an even briefer interview with Möller in which he talks about the influence of Lovecraft on the project.

Comments