Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba (1964): Criterion Blu-ray review

Few films raise questions about the relationship between form and content to the degree that Mikhail Kalatozov’s I Am Cuba (1964) does. This ambitious – and expensive – production was made soon after the Cuban revolution succeeded and was intended as a kind of cultural gift and gesture of support from the Soviet Union, in fact an attempt to embody the meaning of that political event in a film which combined propaganda and art in radical ways. The balance between these elements satisfied few when the film was completed – rejected by many Cubans as a distorted outsider’s view of recent events and by its Soviet sponsors as a formalist exercise with dangerous implications in its emotional call for the active overthrow of an oppressive political system – something useful in the early days of Soviet cinema, perhaps, but threatening to the long-established, deeply entrenched oppressive political system which now gripped the U.S.S.R. And so the film received no release at the time outside of Cuba and the Soviet Union and quickly disappeared.

And yet it had a powerful impact on the nascent Cuban film culture. The first act of the revolutionary government had been the formation of the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematographicos (ICAIC) whose purpose was to foster a national cinema culture reflecting the country’s new identity. This purpose and the relatively limited resources available to Cuban filmmakers were overshadowed when Kalatozov and his cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky arrived bearing the unlimited resources of the Soviet government and set about developing their version of the story of the revolution. With poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko along to develop the script in collaboration with Cuban writer Enrique Pineda Barnet, Kalatozov toured the island and gathered narrative ideas for an episodic film depicting the oppression of the people under foreign (specifically American) influences and the rise of a spirit of resistance leading to the overthrow of the dictatorial Batista regime.

Kalatozov and Urusevsky had developed a remarkably expressive style in their previous films together, The Cranes Are Flying (1957) and Letter Never Sent (1959), which transformed Soviet Realism into a poetic expression of pictorial monumentalism (all those low-angle shots framing people in silhouette against dramatic skies) steeped in heightened emotions, with archetypal characters rising against history and nature to become avatars of the triumph of communism. This approach to cinema reached its apotheosis in I Am Cuba, in which visual technique comes close to obliterating the specificity of the recent revolution, transforming Cuban experience into a series of archetypal moments which come to represent the experience of every society rising to overthrow the crushing weight of capitalism.

At the time, this generalization was rejected by the audience (and officials who had become uneasy about the scale and cost of the production), but those who had worked on the film (or had an opportunity to see it during its brief release) had been shown the remarkable possibilities of cinema and brought that knowledge to their own subsequent productions, despite smaller budgets and more limited resources. (Humberto Solas’ Lucia [1968] provides an interesting comparison, using a similar structure and expressive visual style but more attentive to a social and historical specificity.)

Despite its influence on subsequent filmmakers, I Am Cuba might have remained a forgotten film if it hadn’t been rediscovered in the ’90s and, ironically, revived by American cineastes. With support from Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, Milestone Films restored the film and re-released it after it screened at Teluride in 1992 and the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1993. With three decades’ distance, it was possible to see the film’s artistic achievement separately from its propagandistic purpose and appreciate the remarkable visuals and the emotional resonance of the stories it tells. The heightened melodrama of those stories which had offended people who had recently lived through the revolution now belatedly served the propagandistic aims of the filmmakers – the oppression depicted is intolerable and the audience responds positively to the ordinary people – peasants, workers, students and intellectuals – who take up arms.

The film overwhelms the viewer with its imagery – its striking visual textures derive from Urusevsky’s choice of an extreme wide-angle lens (9.8mm), which fills the 1.33:1 frame with a sense of epic scope and a deep field of focus, and use of infrared-sensitive film, which heightens contrast and transforms green into a silvery white. The verdant island shimmers with an almost mystical energy. But beyond the look of the images, it’s the use of complex camera movement and extreme framing which gives I Am Cuba its particular power. The four narratives are propelled by what frequently seem to be impossible shots, though even less elaborate moves are often breathtaking.

The opening titles run over aerial shots of the island shimmering with that inner silver light; from that, it cuts to a canoe gliding over smooth water beside huts where women do their chores as the voice-over – a woman who speaks for the island itself – evokes a long history of exploitation and oppression, of people used by foreign interests to produce sugar for export, the sweetness of the cane bought with tears. This cuts abruptly to a rooftop bar in Havana, with a jazz band and a beauty pageant and rich tourists relaxing in the sun with their drinks. This turns out to be the first of the film’s “impossible” shots as Urusevsky’s camera prowls the rooftop with its expansive view of the city, picking out details of the privileged foreigners, then descends past balconies to emerge at the side of a swimming pool where it follows a woman in a bathing suit into the water, ducking beneath the surface to capture a swirling crowd of swimmers.

The energy here primes the audience to be carried along wherever Kalatozov wants to take them, immersed in the many disparate places visited by the camera. There’s a sense of travelogue infused with ecstatic energy which the film will use to draw viewers towards the conclusions the filmmakers want them to reach. The air of privilege on the rooftop is abruptly contrasted with a street-level sequence in which a fruit peddler courts a woman named Maria, anticipating their life together despite their poverty. This cuts to a nightclub where a group of American men looking for a good time buy drinks for prostitutes. One of these men, Jim (French actor Jean Bouise, one of the few professionals in the cast), chooses Maria, known here as “Betty”, who unknown to her boyfriend survives by prostitution. Jim insists that she take him back to her place in the slums so he can see how the locals live; her abject humiliation is worsened when, against her wishes, he “buys” her crucifix as a souvenir and her boyfriend arrives before Jim has left.

From this urban drama, the film shifts to the countryside where an elderly man nurtures his small field of sugar cane, helped by his son and daughter. But as they begin to harvest, the landowner arrives to tell the old man that he’s sold the land to the United Fruit Company (a loaded name, since the CIA overthrew the elected government of Guatemala at the company’s request in 1954) and the old man’s right to work the land has been rescinded. Sending his children to town, the old man sets fire to his field and dies there essentially from hopelessness.

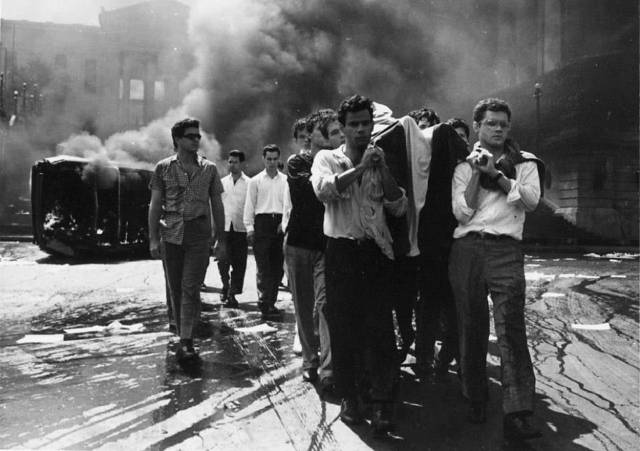

Back in the city, a group of students join the resistance, printing revolutionary pamphlets and contemplating violence. Not only are they at risk of arrest, at any moment they might find themselves victims of police violence. Tensions explode in a riot and a student is gunned down by a corrupt police commander. This culminates in the film’s most audacious shot, where the camera technique vies with the action for audience attention; is this good filmmaking, or merely showing off? Urusevsky calls attention to himself and risks pulling the viewer out of the dramatic moment and yet by the end of the shot we have a sense of implacable historical forces driving an entire population towards an inevitable uprising.

Starting in close up among the crowd in the street as the dead student is lifted and carried away, the camera retreats slightly and suddenly begins to rise up the side of a building, gradually opening up the frame to a more expansive view of the crowd, now unified around the dead student. Up past balconies with people leaning out to watch the movement below, until the camera reaches a walkway across the street and moves laterally through a doorway into a cigar factory where one worker lifts a folded flag and passes it back from one to another as the camera follows, reaching a widow looking out over the street; the revolutionary flag is unfurled and hung out of the window as the camera passes over it and drifts out into the air several stories above the crowd, floating along the street as the crowd grows around the martyr. On first viewing, this is a disorienting shot, though seen more than once the technical achievement becomes clear – and perhaps more impressive because of the ingenuity with which it was conceived and executed; the operator carrying the camera steps back onto a small elevator mounted on the side of the building, steps off onto the walkway and carries it into the factory and between the tables and finally, with only the slightest jarring of the image, attaches it to a small dolly suspended from cables which run from the top of the window to a building a block away down the street. This was achieved long before lightweight cameras and Steadicam rigs were available, the complex and physically challenging move necessarily being coordinated with the choreography of a crowd of hundreds filling the street; it stands as one of the great single-take camera moves of classical cinema.

The exhilarating effect of this shot carries the film into its final movement, set in the mountains from where the guerrillas launch the final campaign against Batista’s forces. An exhausted fighter arrives at a remote farm where he’s met with distrust by the farmer, though the man’s wife offers him food. The farmer wants no part of the fight, refusing to believe that it has anything to do with him and his family. But after the fighter leaves, an air raid surrounds the family with explosions – the wife runs with two of the children, while the farmer tries to protect the third, but the boy is killed. Though he eventually rejoins his wife and the other children, he knows now that it really is his fight after all and he leaves to find the guerrillas to become yet one more member of the force whose historical triumph is inevitable.

Even as Kalatozov and his crew were beginning the long process of production, that seemingly inevitable triumph was under threat – two years earlier, in April 1961, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion signalled the American refusal to accept a free and independent Cuba under Castro’s revolutionary government. As in the case of much of Latin America, the rejection of control by American business interests was unacceptable; but the assertion of American political and economic hegemony pushed nationalists, sometimes less than willingly, towards the influence of the U.S.S.R. In the case of Cuba, this led to the Soviet attempt to place nuclear missiles on the island in October 1962 – the month in which Kalatozov arrived to begin his project. Already the consequences of the revolution were outstripping the projected film’s intended depiction of the causes. For all its power, I Am Cuba was somewhat redundant even before a single frame was shot, yet another factor in its rejection at the time.

And so, rediscovered decades later, it stands more significantly as a work of cinematic art than as propaganda. Its approach to revolution is aesthetic rather than political. Compare it, for instance, to Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle Of Algiers (1966) with its rigorously political treatment of armed resistance to French colonial control in North Africa, a guerrilla war which had influenced the tactics used by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Cuba. Where Pontecorvo’s film can stand as an historical document of revolution, Kalatozov’s is a fever dream of the idea of revolution, a fascinating, emotionally wrought visual fantasia which expresses an innate human desire to seek justice and see the end of oppression. I Am Cuba is a cinematic masterpiece which transcends the specifics of history and politics.

*

The disk

First released on DVD by Image Entertainment in 2000, and subsequently in a box set by Milestone in 2007, I Am Cuba was long overdue for an upgrade; Criterion’s edition (available in a dual-format set and as a stand-alone Blu-ray) uses Milestone’s 4K restoration from a fine-grain positive; it looks gorgeous, capturing the distinctive qualities of Urusevsky’s 9.8mm infrared imagery – silver foliage, black skies with intricately textured clouds. The soundtrack, mastered from original 35mm magnetic tracks, is the clearest it’s been on disk. Along with the Spanish-language track, Criterion have included the Russian track (which was the only option on the original Image disk). This alternate track is interesting in itself; rather than a full dub, it has a Russian voice-over repeating everything we can hear in Spanish in the background, which itself can be viewed as a kind of appropriation of the Cuban experience by the Russian filmmakers.

The supplements

Apart from a newly-recorded interview with cinematographer Bradford Young (2023, 22:03) discussing Urusevsky’s work, the extras have been ported over from Milestone’s Ultimate Edition DVD set. There’s a lengthy interview with Martin Scorsese (2003, 27:48) in which he recounts his discovery of the film and his enthusiasm for Kalatozov and Urusevsky’s technique. Most substantial is Vicente Ferraz’s documentary I Am Cuba: The Siberian Mammoth (2004, 1:31:50), in which the Brazilian filmmaker travelled to Cuba to track down members of the cast and crew to uncover the story behind the making of the film. Many of the participants have conflicted feelings about the project and its relationship to the events it drew on, but few of them were aware that the film had been rediscovered more than a decade earlier and was now highly regarded outside of Cuba.

There’s also a trailer (1:51) and the booklet essay is by Cuban film scholar Juan Antonio Garcia Borrero.

Comments