Clearing the docket: Summer 2025

Time to clear the docket once again and briefly survey what I’ve been watching over the past few months.

Arrow

V Cinema Essentials: Bullets & Betrayal (Various, 1989-94)

This set definitely deserved some coverage. With Japanese cinema attendance in decline and home video on the rise in the late 1980s, studios began to produce low-budget direct-to-video movies for the changing market. Toei was one of the first, introducing their V-Cinema line with Shundo Okawa’s Crime Hunter: Bullets of Rage (1989), which established the template with a fast-paced story packed with action, violence, and an absurdly pulpy plot involving a cop bent on revenge who teams up with a gun-toting nun to track down millions in stolen loot in a strangely ersatz setting which seems to be in an alternate American city. Opening with this, Arrow’s five-disk set brings together nine equally outlandish movies which range from yakuza stories (Banmei Takahashi’s Neo Chinpira: Zoom Goes the Bullet [1990], Kazuhiro Kiuchi’s Carlos [1991]) to psychological suspense (Shinichi Nagasaki’s Stranger [1991]) to heist movies (Yoicho Sai’s Burning Dog [1991], Yasuharu Hasebe’s Danger Point: The Road to Hell [1991]) and hitmen, both amateur and professional (Teruo Ishii’s The Hitman: Blood Smells Like Roses [1991], Danger Point). Two of the movies centre on female assassins: Toshiharu Ikeda’s Female Prisoner Scorpion: Death Threat (1991) resurrects the iconic ’70s character as a trained assassin sent undercover into a prison to find and kill the original Scorpion only to be betrayed and reinvent herself as a symbol of defiance against illegitimate authority; while Masaru Konuma’s XX: Beautiful Hunter (1994) has a woman groomed as an assassin by a religious cult from an early age finding herself in an untenable position when she falls in love with a witness to one of her hits and is ordered by the cult leader to kill the man.

Having seen a lot of North American direct-to-video movies from this same period, I didn’t have high expectations for this collection, but I should have known better since major figures like Takashi Miike and Kiyoshi Kurosawa got their start in this realm of exploitation. The biggest surprise was just how well-made most of these films are; despite relatively small budgets and the disposable nature of home video, they’re shot like theatrical movies, with well-crafted scripts and often very elaborate action sequences handled by some notable directors. It’s also a pleasant surprise to find someone as iconic as Jô Shishido turning up in a couple of films – as the protagonist’s uncle in Takahashi’s Neo Chinpira, which is a surprisingly complex deconstruction of the yakuza genre, and as one of a pair of hitmen who, perhaps inspired by the team in Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964), become too curious about the man they’ve been hired to kill and embark on an investigation of a heist which proves extremely dangerous. In both films, Shishido is teamed up with the younger Shô Aikawa, here near the beginning of a very successful career.

Mostly shot on 16mm, these movies have a cinematic quality which belies their origins as disposable exploitation; Arrow’s transfers are much more impressive than expected. Each movie gets an introduction from critic Masaki Tanioka, while there are also several interviews with writers and directors, as well as a number of visual essays on various aspects of the genre. The set is an excellent companion to Arrow’s recent J-Horror Rising.

*

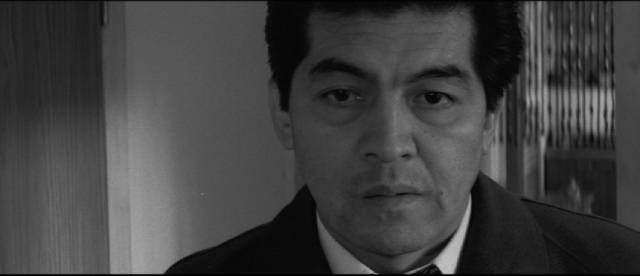

The Threat (Kinji Fukasaku, 1966)

Earlier movies which inspired this genre have also received fine new releases from Arrow. Kinji Fukasaku began his directing career in 1961, making a string of crime-centred B-movies (more than a dozen in eight years) before a first attempt to break into the international market with the endearingly silly The Green Slime (1968). Despite his subsequent success with violent, politically-charged action movies, those early films have been largely inaccessible to a western audience, though last year’s release on disk of Wolves, Pigs and Men (1964) opened the door a crack. Now comes The Threat (1966), which was made immediately after Wolves. A gripping noir in which a salaryman and his family are held hostage by two escaped criminals who have kidnapped the infant grandson of a wealthy businessman, it delves into the psychological stress faced by lower middle-class Japanese men trapped by the demands of the post-war economic system which enslaves them to a materialism which defines social status while stripping men of self-respect. Forced by the kidnappers into helping collect the ransom while they threaten his wife and son – who come to view his compliance as weakness and cowardice – he contemplates running away and leaving his family to their fate before finding a way to save them and the baby and defeating the criminals. Bleak and intense, The Threat is a masterful thriller which displays Fukasaku’s acute understanding of Japan’s post-war social and economic stresses.

*

A Certain Killer/A Killer’s Key (Kazuo Mori, 1967)

While Fukasaku was near the start of his career, Kazuo Mori was three decades into a long and very prolific career when he directed A Certain Killer and A Killer’s Key back-to-back in 1967. A talented journeyman – he directed several of the Shinobi ninja movies, several Zatoichis, and even one of the Daimajin movies – here he was working in the ’60s crime genre (from scripts co-written by the much more idiosyncratic Yasuzo Masumura), specifically the sub-genre centred on ultra-cool hitmen (exemplified by Takashi Nomura’s A Colt Is My Passport and Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill [both 1967], both of which starred the iconic Jô Shishido). Although not directly related – star Raizo Ichikawa plays different but similar characters in each, a loner with a seemingly conventional life who takes contracts for yakuza gangs, whom he knows will betray him to avoid paying his fee – both depict the killer’s careful planning and execution of his contracts before detailing the ways in which things unravel in the aftermath, all while the killer displays no emotion and reveals nothing personal.

Both the Fukasaku and Mori releases include commentaries and featurettes which provide context for the films.

*

Sleep (Michael Venus, 2020)

I’m not sure that Michael Venus’ Sleep (2020) is entirely successful, but It’s certainly visually striking and has a fascinating central performance by Gro Swantje Kohlhof as Mona, a woman who goes to a small town when her mother suffers a severe breakdown in the local hotel. As the title suggests, the narrative seems to inhabit the unstable border between waking and sleep where perceptions drift between reality and fantasy and what might be seen is unreliable. In this liminal space family history blends with national trauma as Mona learns about her own origins among the fascist bourgeoisie of Germany which, rather than disappearing completely after defeat in World War Two, simply went underground where its malignant beliefs have festered. The disk has an excellent image, supplemented by a commentary, a couple of video essays, several brief deleted scenes, and several interview featurettes.

*

The Bloodhound (Patrick Picard, 2020)

Having made movies on very limited budgets, and knowing just how difficult that is, I’m always interested in what other filmmakers do with limited resources. Patrick Picard’s The Bloodhound (2020) is a minimalist version of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”, made perhaps appropriately during the pandemic as the story deals with a family oppressed by disease. Francis (Liam Aiken) is summoned by his old college friend JP (Joe Adler) to visit the family home where JP lives with his reclusive twin sister Vivian (Annelise Basso), who is barely seen and may be suffering from a terminal illness, and possibly madness, which JP fears will also claim him. Much of the film’s tension remains buried beneath banal interactions; there are class issues – Francis is struggling financially while JP is wealthy enough that money means nothing to him – as well as sexual tension arising from unacknowledged homosexual feelings on JP’s part. Bloodhound is a rather chilly exercise in formalism, with occasional hints of supernatural menace, but the characters’ psychological games remain interesting for the brief 72-minute running time. There’s a commentary, a lengthy making-of, and four very brief experimental shorts by Picard.

*

A Simple Plan (Sam Raimi, 1998)

In the early ’90s Sam Raimi was trying to emerge from the shadow of his Evil Dead trilogy and show that he was capable of more than those inventive horror-comedies which were popular with a particular fan base, but not so much with a wider audience. Crimewave (1985) had gone off the rails, but Darkman (1990) was a moderately successful comic book adaptation; the western pastiche The Quick and the Dead (1995) also made some money, despite a weak script. Yet it seemed he was still confined to a genre ghetto. He might have seemed an unlikely fit for a project which had gone through years of development with a number of high-profile directors attached at different times – Mike Nichols, Ben Stiller, John Dahl, John Boorman, all of whom dropped out because of either scheduling conflicts or creative differences – but A Simple Plan (1998) proved to be the perfect vehicle for Raimi to remake himself as a mainstream filmmaker.

In many ways, this was a remarkable and unexpected change of direction for Raimi. There isn’t a trace of irreverent slapstick in A Simple Plan; it’s a study in small-town desperation which grows increasingly darker as it moves inexorably towards a grim conclusion which leaves its protagonist with a terrible burden of self-knowledge. This is Hank (Bill Paxton, in his best role), a man living a comfortable lower middle-class life in a small Midwestern town with his pregnant wife Sarah (Bridget Fonda); there aren’t any real prospects for advancement at the feed mill where he works, but not much to complain about otherwise.

Hank feels a frustrated sense of responsibility towards his brother Jacob (Billy Bob Thornton, again in one of his finest roles), who seems carefree and perhaps a little simple minded; unemployed, Jacob hangs out with his buddy Lou (Brent Briscoe), goofing around, getting drunk. The uneasy balance between the brothers is upended one day when they discover a small plane crashed in snowy woods; on board is a dead pilot and a gym bag full of money. Hank’s initial response is to report the find to the authorities, but the other two want to keep the money – it’s the only chance any of them will ever have to break out of their dead-end lives. Although reluctant, Hank finally agrees, but only if they wait to see if anyone comes looking for the money and, most importantly, none of them tell anyone about the find.

Of course, it’s a tough secret to keep and Hank immediately shows the loot to Sarah, who quickly goes full Lady Macbeth, frustrated by Hank’s caution. As winter lingers on, the stresses among the characters increase and bad decisions are made – fearing discovery, Jacob kills a local farmer compounding their secret with an actual crime. Eventually a man comes looking for the money, claiming to be an FBI agent, although he’s actually the dead pilot’s partner in a kidnapping. The final confrontation at the crash site ends with an eruption of bloody violence and Jacob, unable to deal with the weight of the bad decisions and terrible actions which have led to this point, demands that Hank put an end to his suffering.

The script by Scott B. Smith, adapted from his own novel, is beautifully constructed with an almost classical conception of fate rooted in the characters’ all-too-human flaws. And those characters are developed in rich detail, giving the cast something deep and substantial to work with, to which everyone involved responds with some of their finest work. All of this is beautifully shot by Alar Kavilo (whom I met in 1993 when I was an extra on the set of Heads in Winnipeg) during a bleak Minnesota winter, supported by one of Danny Elfman’s more restrained scores. If Raimi’s earlier work resembles the exhilarating play of a precocious adolescent, A Simple Plan is the mature work of a fully developed artist – and it certainly provided a boost to his mainstream career; after the even more atypical Kevin Costner baseball romance For Love of the Game (1999), he made the supernatural thriller The Gift (2000) starring Cate Blanchett and Keanu Reeves, and then hit commercial (if not creative) gold with the corporate behemoth Spider-Man trilogy. Unfortunately, nothing since has possessed his early sense of iconoclastic fun, or the sheer dramatic power of A Simple Plan.

Arrow’s new 4K restoration from the original negative looks gorgeous, supplemented with two new commentary tracks (though strangely without Raimi), plus several new and archival interview featurettes (again without Raimi).

*

Radiance

I haven’t been keeping up with the steady flow of releases from Radiance, though every month there’s something I’m interested in. Nonetheless, the few I have watched recently show something of the label’s impressive range.

Tony Arzenta (Duccio Tessari, 1973)

Like so many Italian directors, Duccio Tessari followed the always-evolving trends of commercial filmmaking, beginning with sword-and-sandal adventures in the early ’60s, through tongue-in-cheek post-Bond espionage movies, spaghetti westerns, comedies, giallo and poliziottescho. While 1973’s Tony Arzenta (Big Guns) has familiar elements from the latter – dynamic car chases, some nasty violence – the casting of Alain Delon in the title role as a mob hitman also brings to mind the cooler style of Jean-Pierre Melville for whom Delon starred in three movies, including as the iconic anti-hero hitman in Le samouraï (1967). Delon, with a wife and young child, has had enough of the business and tells his boss (Richard Conte) that he’s retiring; while that’s okay with the boss, his partners in the mob vote to kill Arzenta because he knows too much. Unfortunately for them their car bomb kills his wife and child instead and he undertakes a campaign to wipe out all the high-level figures in the mob, something for which his skills prove very useful, though his actions cause collateral damage to his friends and family. The 4K restoration looks excellent and comes with a select-scene commentary, an archival interview with Delon, and a featurette with Mike Malloy about where the film fits in the poliziotteschi genre.

*

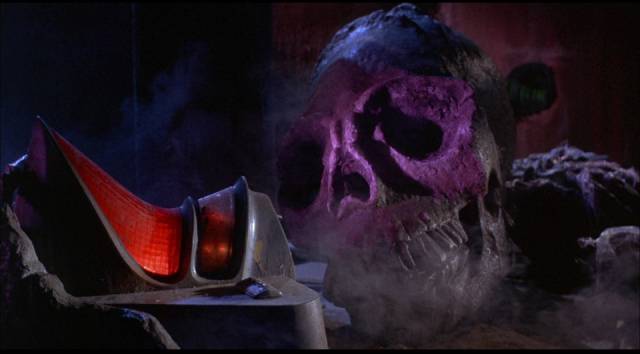

Planet of the Vampires (Mario Bava, 1965)

How many times have I bought Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965) since I first saw it on VHS sometime in the ’80s? Probably at least five including this new Radiance edition. Perhaps objectively the movie is just cheap pulp sci-fi, as generic as many B-movies of the ’50s and ’60s … but Bava’s visual flair raises it far above the crowd, and this new 4K restoration makes it even more impressive as an example of imagination and technical ingenuity over limited resources. It is to sci-fi what Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945) is to film noir. Bava’s use of colour and various in-camera trick shots give the threadbare sets and doom-laden story a fascinating, surreal quality. The design famously prefigures elements of Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), while the reanimated dead astronauts bridge the gap between traditional zombies and George A. Romero’s more menacing walking dead. The stunning transfer is accompanied by Tim Lucas’s commentary, recorded for an earlier Kino release, an archival interview with Lamberto Bava, a super-8 home viewing condensed version, a couple of Trailers From Hell commentaries, and a new 41-minute documentary which explores the links between science fiction and the Gothic. There’s also a booklet containing a translation of the source short story by Renato Pestriniero.

*

Daiei Gothic (Various, 1959-68)

And speaking of Gothic, Radiance’s three-disk Daiei Gothic set collects a trio of traditional horror movies produced by a company noted for its period genre films, two in new 4K transfers, the oldest designated only as “a high-definition digital transfer”. All three look excellent, with subdued colours and deep shadows producing an atmospheric mood.

Based on the much-adapted 19th Century kabuki play, The Ghost of Yotsuya (1959) – directed by the prolific Kenji Misumi, perhaps best-known for his work on many Zatoichi and Lone Wolf and Cub movies – changes its protagonist from a cold-blooded opportunist who kills his wife and child in order to get ahead socially into a decent man manipulated by others and undeserving of his fate. Nonetheless, after plot machinations which are designed to free him from his marriage so that the daughter of a powerful man who has fallen in love with him can have him, his wronged wife returns as a ghost seeking revenge.

In Satsuo Yamamoto’s The Bride from Hades (1968), a lowly samurai who is satisfied with his life faces pressure from his family to improve his position through marriage. During an annual festival for the dead, he meets a beautiful woman and her servant during a ceremony by a river. The pair come to visit him in his humble home, but the idea of romance quickly becomes a problem when he realizes that the two women are ghosts trying to cling to life. His attempts to bar the ghosts from entering his home are foiled by a servant who removes one of the many charms pasted over doors and windows in return for some money from the ghosts. Having slept with the ghost, the samurai joins her in death as the festival ends.

Tokuzo Tanaka’s The Snow Woman (1968), based on a legend included in a collection by Lafcadio Hearn which was previously adapted as an episode in Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964), is the story of a woodcarver who, with his mentor, takes shelter from a winter storm in an abandoned hut; as they sleep, a spirit arrives and drains the life from the older man, but spares the younger, telling him that he must never tell what he’s seen or he too will die. Back home, as he sets about carving a Buddha for the temple, he encounters and falls in love with a beautiful woman. They marry and have a son and he competes with another sculptor to create the best statue, but eventually tells his wife the story of his encounter with the snow woman. It’s no surprise that his wife is actually the spirit and she’s not happy that he’s broken his promise never to speak of that night – but because of their son she spares the man and instead just leaves, disappearing into the snow.

The first two films each get a commentary and all three disks include a featurette which provides some context.

*

There are almost three-dozen more releases to cover in my next post(s)…

Comments

Thanks Kenneth! Now I have some more Japanese films to add to my collection. The Threat sounds like a good one to start with….

There’s always more to catch up with – I’ve just been dipping into some French crime movies I hadn’t seen before…