Crime, class and noir in ’50s British cinema

In the midst of my rather chaotic recent viewing, three black-and-white British films from the 1950s which I hadn’t seen before…

Indicator

After discovering the British label Indicator back in January 2018 when I bought their edition of Sydney Pollack’s Castle Keep (1969), for the next seven years I bought almost everything they released, sometimes just because they were releasing it – whatever it might be, it was guaranteed to be an interesting title given a exemplary presentation. I have slowed down more recently, largely because of financial concerns, but also because I’d built up a backlog and had decided to be a bit more judicious, particularly as more releases seemed to be duplicating titles I already owned in acceptable editions from other companies or were less interesting (to me) mainstream titles. I had no interest in a Richard Pryor/Gene Wilder box set, or Norman Jewison’s … And Justice For All, and had quickly traded in the Stanley Long Adventures … box set after a dispiriting slog through those unfunny ’70s Brit sex comedies.

I do have a couple on order at the moment, though, and picked up several at one of my recent trade-in sessions.

The Gentle Gunman (Basil Dearden, 1952)

The most surprising thing about The Gentle Gunman (1952) is the mix of criticism and sympathy in its story of IRA members engaged in terrorist activity in the early days of World War Two. Although I was aware that the Irish Republic, while officially neutral, saw Hitler’s Germany as an ally in the centuries-long resistance of the Irish to English occupation and oppression, I don’t think I’d heard about the IRA’s bombing campaign in London during the Blitz. The first act of the film, adapted by playwright Roger MacDougall from his own 1950 stage play, has Matt Sullivan (Dirk Bogarde) arriving in London looking for his older brother Terence (John Mills), who has disappeared. He’s concerned that Terence has turned traitor to the cause, and steps in to deliver a bomb his brother was supposed to plant in an Underground station. Inexperienced, Matt panics when he realizes that the station platform is crowded with people sheltering from an air raid, including some children. Terence appears and grabs the bomb, throwing it into the tunnel just before it explodes.

Back at the rooming house, Matt sees the police arrive and arrest the bomb makers, seeming to confirm that Terence has betrayed the team. But Terence helps Matt escape from the police and tries to explain that seeing the English struggling to survive the German attacks has made him realize that these are ordinary people, just like the Irish, and no longer considers them (as opposed to the government) to be his enemy. He’s come to think that there must be other, non-violent ways to achieve Ireland’s political aims. Matt sees all this as self-justification for disloyalty and cowardice, and returns to Ireland.

Most of the film then takes place in and around a country garage where the various characters hash out the nuances and contradictions of their activities against the English. Molly Fagan (Barbara Mullen) is a pacifist, bitter that her husband died on a mission, desperate to keep her son Johnny (James Kenney) out of the fight, while her daughter Maureen (Elizabeth Sellars) is a fanatic who believes that anything less than death in the cause is a waste of a man’s life. The cell is led by Shinto (Robert Beatty), who has an unshakably black-and-white view of the conflict and recruits Johnny to undertake a dangerous mission, while Maureen, once Terence’s girlfriend, switches her attention to Matt, pushing him to throw himself whole-heartedly into the fight.

As the mission goes sour and Johnny is fatally wounded, Terence returns, ironically having succeeded where Johnny and Matt failed, though Shinto refuses to listen to what his former ally has to say. In the end, the film pulls back from tragedy and leaves the arguments unresolved; in fact, having approached a grim climax, it abruptly turns light with a touch of comedy. This last has actually been telegraphed by framing the story with an on-going argument between the local doctor (Joseph Tomelty) and a pompous Englishman (Gilbert Harding) who comes to stay with him on holiday, where they circle around the history of England’s colonial oppression and whether or not violent resistance is justified – these scenes, despite the seriousness of the issues, are played for comedy in the familiar Ealing mould and clash uneasily with the political melodrama with which the film is mainly concerned.

Dearden makes the most of some location shooting and handles many of the scenes well – both the arguments among the characters and several taut action sequences – and the script doesn’t shy away from English historical culpability, though it obviously favours Terence’s views about non-violent solutions. The film’s biggest strength is Dearden’s sense of place, whether the dark streets of London under attack or rural Ireland, all of which benefits from Gordon Dines’ atmospheric cinematography.

Where it’s a bit rocky is in the cast, particularly the two leads; John Mills makes little effort to essay an Irish accent, though one does occasionally creep in which just draws attention to his inconsistency, while Dirk Bogarde seems uncomfortable in his role – an edgy, cerebral actor, he doesn’t have much depth to work with here. The rest of the cast fare better, with Sellars the stand-out as the fanatical Maureen, whose own mother eventually points out is in love with death, attaching herself to one man after another and urging each in turn to sacrifice himself to feed her own anger, death itself carrying an erotic charge for her.

Indicator’s 4K restoration looks and sounds excellent. The film is introduced by Dearden’s son James Dearden and is accompanied by an audio interview with Bogarde from 1983. There’s a half-hour conversation between critics Matthew Sweet and Phuong Le and a wartime propaganda short starring John Mills.

The Ship That Died of Shame (Basil Dearden, 1955)

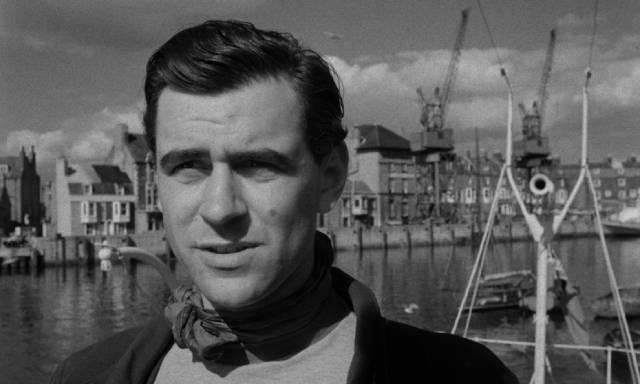

Adapted from a story by Nicholas Monsarrat, The Ship That Died of Shame (1955) is a fairly straightforward post-war crime movie complicated with an unconvincing allegorical overlay. Made three years after The Gentle Gunman, the film returns to the war for its first act; a fast gunboat attacks oil tanks on the coast of France and makes its escape under enemy fire. On board are the commander, Bill Randall (George Baker), his second-in-command George Hoskins (Richard Attenborough), and engineer Birdie Dick (Bill Owen). Elements of class are established, although here somewhat sublimated by the exigencies of war. Back ashore, Randall marries Helen (Virginia McKenna), the woman who gives meaning, purpose and stability to his life … but this lasts only briefly as she dies in an air raid, leaving him psychologically and emotionally adrift.

After the war, with the boat retired, Randall tries to establish himself in business, but he can’t make a go of it. Even worse, he’s waited too long to reclaim the position he had before the war and his old boss won’t take him back. Facing grim prospects, he has a chance meeting with Hoskins at a servicemen’s club. His former subordinate seems to be doing quite well and makes a proposal – their old boat is up for sale and Hoskins suggests that they buy it, fix it up and go into business. Randall gets his drift – he’s proposing a smuggling operation. Nothing serious, just wine and cigarettes and such, things hard to come by as they remain scarce during post-war austerity.

Randall has mild moral qualms, but he’s desperate and no longer has the wise counsel of Helen to counter Hoskins’ persuasive arguments. And so the pair buy the boat and, with the help of Birdie, re-fit it. With the skills they honed during the war, they make fast trips across the Channel, slipping past the coast guard and making a lot of money. For Randall and Birdie, this is more about the love of the operation than it is a commitment to criminal enterprise, and that naivete gives Hoskins an increasing degree of power over them; the old class divisions have been swept away by the war, opening a path for a working class opportunist like Hoskins to step in and make money, while Randall and Birdie cling to their former roles in denial of this new order.

If Randall blindly holds on to a sense of decency as he engages in criminal activity, the aristocratic Fordyce (Roland Culver) has submitted to circumstances and, in a state of seedy decline, has established himself more profitably than even Hoskins in the smuggling business. After attempting to eliminate these small rivals, Fordyce finds himself intimidated into an uneasy partnership with Hoskins, lining up new jobs which are less innocent but more profitable. Hoskins keeps a lot of the details hidden from his partners, who are too willing to turn a blind eye to what they might be carrying back across the Channel.

But here’s where the story takes an awkward turn; the boat itself begins to balk at what it’s being used for. The engines become inexplicably erratic, the rudder becomes unresponsive – the machine manifests the conscience Randall has suppressed, making the crew vulnerable to interception by the coast guard. As some of this resistance is eventually passed on to Randall and Birdie, Hoskins becomes more aggressive, taking more risks. Everything comes to a head when he accepts the job of bringing a suspicious man across from France and Randall discovers that he has helped a child murderer escape from the police. Hoskins and Fordyce have a final, fatal falling out and, having had enough, the boat essentially commits suicide by running itself onto the rocks.

While the crime story and its roots in the collapse of the class system following the war is reasonably well-handled, with the characters given some depth and the increasing risks building tension, the allegory feels awkwardly shoe-horned in. Dearden worked with the supernatural and allegory a number of times during his career – The Halfway House, They Came to a City (both 1944), the framing story of Dead of Night (1945), The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) – but here the fantasy element not only remains unconvincing, it distracts from the more interesting drama of these men who forged a sense of purpose amidst the dangers of the war only to find themselves morally adrift in the aftermath.

Attenborough dominates with his enthusiastic performance as the opportunistic Hoskins, while Owen does his usual sturdy job as the working class professional Birdie. Baker, however, makes a rather dull hero as Randall. The biggest surprise, though, is Roland Culver as the aristocratic Fordyce, the embodiment of the upper class gone to seed, a role at odds with his usual portrayal of members of a self-assured establishment, often as an officer, a solicitor or a magistrate. Evoking memories of those roles, his presence here highlights a radical shift in the post-war class structure as Fordyce finds himself powerless against the working-class upstart Hoskins.

Once again, Dearden’s work is greatly aided by Gordon Dines’ cinematography, which is very atmospheric in the many night sequences, and gets a fine presentation in Indicator’s 4K restoration. James Dearden provides another brief introduction and film historian Neil Sinyard speaks about Ealing and this film’s themes and reception. There’s a feature-length interview with Attenborough from 2001, and another propaganda short from 1940 warning about the danger of talking too much.

*

An Inspector Calls (Guy Hamilton, 1954)

Although not an Ealing production, Guy Hamilton’s An Inspector Calls (1954) makes a nice companion piece for Dearden’s film – it’s another allegory with a critique of class at its centre, though set in the years just before World War One. Adapted from J.B. Priestley’s 1945 play, the film doesn’t stray far from its stage origins, remaining confined to a single set except for brief flashbacks which gradually reveal the story of a country girl whose independence is systematically crushed by a class system which views her as barely human. The instruments of this system are the privileged Birling family who are introduced at a celebratory family dinner to mark the engagement of daughter Sheila (Eileen Moore) to Gerald Croft (Brian Worth). Mr. Birling (Arthur Young), a wealthy factory owner, smugly announces his hopes of receiving a knighthood for his business and political activities.

The meal is interrupted by the arrival of a man identified as Inspector Poole (the inimitable Alastair Sim), who says that he has a few questions regarding a young woman named Eva Smith (Jane Wenham), who has arrived at the infirmary an apparent suicide. No one can imagine what this has to do with the family, but as Poole questions each in turn he reveals that every member of the family has had an encounter with Eva which changed her life in increasingly detrimental ways. On arriving from the country, she had obtained a job at Birling’s factory, but when the women he employs had asked for an increase in their meagre wages he had singled Eva out as a troublemaker and fired her.

Next, it’s revealed that Sheila had encountered Eva in a shop where she had found work. Angry that her mother and the staff didn’t agree with her about a hat she liked, Sheila accused Eva of being rude and demanded that the manager fire her or Sheila would never enter the shop again. Having now been sacked twice, Eva’s prospects were very bad and she resorted to prostitution. It turns out that Gerald had met her in a bar and, realizing that she was not really “that kind of girl”, he set her up as his mistress in a small flat, keeping her for several months over the summer. This news puts an end to the engagement and Sheila returns his ring.

In desperation, Eva had applied to a local women’s charity which helped the “deserving poor”, but under severe questioning from the chairwoman lost any potential sympathy by telling the board that she was pregnant, but refused to name the young man responsible because she didn’t want to ruin his life. Appalled, the chairwoman – Mrs Birling (Olga Lindo), of course – refuses the charity’s help and sends Eva away. When Poole asks Mrs. Birling who she believes should have been responsible for the young woman, she haughtily agrees that the “drunken young man” who got her pregnant should have taken care of her.

By this point, it’s obviously no mystery who that young man is – the Birlings’ son Eric (Bryan Forbes) has been drinking heavily all evening, despite his parents wilfully ignoring his obvious problem. He confesses that he took advantage of Eva and that when he learned of the pregnancy, he stole £50 from his father’s company, but she refused the ill-gotten money and instead asked for help from his mother’s charity. Mr. Birling is more shocked by the theft than all the cumulative actions which had led to Eva’s destruction.

The parents’ efforts at self-justification are countered by Poole’s assertion that everyone in society is connected and all share a mutual responsibility for treating others with care. But with him absent from the room, Mr. and Mrs. Birling begin to question everything they’ve heard, their doubts seemingly confirmed when Gerald returns and tells them that he’d asked a policeman he knows and it turns out that there is no Inspector Poole. A call to the infirmary confirms that there has been no suicide. Yet, while the parents see this as letting them off the hook for their actions, Sheila and Eric can’t deny that their behaviour has been unacceptable, signalling an awakening of class consciousness on the eve of the war which would brutally put an end to the privileged complacency of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. At which point, there’s a call announcing that a young woman, an apparent suicide, has died on the way to the infirmary and a policeman will be coming around with some questions for the family.

Despite the parents’ desire to retreat into the comforts of their class-based security, it seems that they won’t be able to escape their moral culpability after all. The mysterious Poole has been some kind of avatar of conscience and social responsibility, the play a didactic declaration of Priestley’s socialist views and a critique of the dehumanizing effects of Britain’s moribund class system. The script’s strengths lie in its sharply-drawn characters which transcend their thematic purpose as social types. The excellent cast is, not surprisingly, dominated by Sim who invests Poole with his signature wry humour as his insistently probing questions gradually force each character in turn to accept responsibility for actions which thoughtlessly harmed a person whom they never considered to be a fully autonomous human being.

Although An Inspector Calls was only Guy Hamilton’s third feature, he handles the cast well and never lets the restricted setting make it feel cramped and stagy. StudioCanal’s 4K restoration has a richly detailed image which brings out the excellent quality of Ted Scaife’s cinematography (three years later Scaife would shoot Jacques Tourneur’s atmospheric masterpiece Night of the Demon [1957]). written in 1945, set in 1912 and filmed in 1954, An Inspector Calls remains a timely drama which simply asks that people be decent to one another.

The dual-format set includes a brief interview with actress Jane Wenham, a discussion of the film and its source by critic Anna Smith, and an archival commentary from David Del Valle.

Comments