Recent disks from England, part two: Arrow

Sales are insidious. They suck you in with the promise of savings, and you end up spending way more than you otherwise would have, buying things you probably wouldn’t have wanted at full price. On the other hand, they can make you take a chance on something you know little or nothing about – after all, it’s only half-price! With Arrow’s pre-Christmas sale, I bought a mix of the known and unknown (in one case even buying something I already have – one of the hazards of a large collection!), some classics, some recent movies.

Pieces (Juan Piquer Simon, 1982)

I guess I have a soft spot for Juan Piquer Simon because of Slugs (1988). I’ve seen several of his other movies, but they don’t quite have the same mad charm – The Rift (1990), Cthulhu Mansion (1992). His best known, and apparently most-appreciated by fans, is Pieces (1982), an attempt to emulate the then extremely popular American slasher. A friend lent it to me a few years ago, but I wasn’t particularly impressed; still, since I was in a buying mood and it was only £8, why not add it to the basket?

The structure is there – prologue in the past in which a young boy chops his mother into pieces with an axe; jump to the present where someone is cutting students at a small college to pieces with a chainsaw (we know that one of the adults must be that boy grown up, but have to wait until near the end for the reveal). Like so many European movies supposedly set in the States, there’s an unreality about it – even the American actors (Christopher George, Lynda Day George, Edmund Purdom) seem off, as if they can’t quite find an authentic tone. No one’s behaviour is natural, the worst offender being Paul L. Smith, who mugs so outrageously as the principal red herring that he almost single-handedly transforms the movie into a comic parody of the genre. He seems to still be playing Bluto from Robert Altman’s Popeye (1980).

Satanic Panic (Chelsea Stardust, 2019)

I had expected nothing but cheap cheese from Chelsea Stardust’s Satanic Panic (produced by Fangoria in 2019), but was pleasantly surprised by this horror comedy’s wit and technical polish. It’s in a class with Christopher Landon’s Happy Death Day 1 and 2 and Freaky. Like those movies, it finds just the right balance between the horror and the comedy, the cast never mocking the material even at its most absurd. Here, a young woman scraping by with a pizza delivery job finds herself in a wealthy suburb populated by smugly arrogant people who don’t tip and also happen to be Satanists in need of a sacrificial virgin before sunrise. Sam (Hayley Griffith) has to team up with the daughter of the coven’s leader to save herself and foil their plans to birth a demon and take over the world.

Well-paced, written and performed with wit and humour, the movie is an entertaining riff on class conflict with the rich literally demonically self-serving, using the poor as raw material to increase their wealth and power. The cast, led by the very appealing Griffith, has Rebecca Romijn as the coven leader, Ruby Modine as her daughter, Jerry O’Connell (briefly) as her dissolute husband and Arden Myrin as her rival, itching to take control of the coven away from her.

The Grand Duel (Giancarlo Santi, 1972)

It doesn’t happen often, but occasionally when I watch a movie I’ll get to a scene which suddenly seems really familiar, although what led up to it doesn’t. That happened while I watched Giancarlo Santi’s The Grand Duel (1972), a late period spaghetti western which avoids the mocking parody of the Sabata and Sartana movies – and is thus more to my taste. Once again Lee Van Cleef stars as an expert gunfighter who takes on the violent family which controls a small town. Here he’s an ex-marshal out to clear the name of a wrongfully accused man. My sense of deja vu really kicked in during a black-and-white flashback, one of a series, which gradually reveals what really happened when the bad guys’ family patriarch was assassinated one night.

The familiarity was explained when I checked my catalogue and discovered that I already had a copy of the movie on a Mill Creek double-feature disk (with Enzo G. Castellari’s excellent Keoma [1976]) and had watched it several years ago. No matter, the Arrow disk is definitely an improvement, both in quality of image and extras (more than three hours of featurettes plus a commentary track compared to Mill Creek’s bare bones release). Santi, a former assistant to Sergio Leone, harks back to the darker, more serious westerns of the mid-’60s, making good use of Van Cleef’s established persona and providing the ex-marshal with strong opposition in the form of the three vicious Saxon brothers – one politically ambitious (Horst Frank), one the local sheriff obsessed with revenge for his father’s murder (Marc Mazza), and one a psychotic degenerate (Klaus Grunberg). Gunfights are effectively staged and the action benefits from a fine score by Luis Bacalov.

Zombie for Sale (Lee Min-jae, 2019)

Lee Min-jae’s Zombie for Sale (2019) is nothing like Yeon Sang-ho’s Train to Busan (2016) and its sequel, Peninsula (2020), but there are hints that it takes place in the same universe, with an eruption of zombie mayhem overrunning Korea. The emphasis is very different, though, recalling domestic horror comedies like Kim Jee-woon’s The Quiet Family (1998). In a small rural town, a family running a failing gas station find themselves in possession of a lone zombie, a confused young man who mostly chows down on heads of cabbage. When he bites the father, rather than passing on the zombie infection, the bite rejuvenates him. The family quickly work out a money-making scheme; they charge the local old folk for a bite with the promise of renewed youth. It all eventually goes wrong because while some people, like the father, are immune to the worst effects of the zombie virus, others aren’t and soon the town is overrun. But even as things escalate, Lee maintains his focus on the family and their interpersonal conflicts. The film has genuine charm, though it would probably disappoint anyone expecting another Train to Busan.

The Stylist (Jill Gevargizian, 2020)

Jill Gevargizian’s The Stylist (2020) is a slow-burn piece of character horror somewhat reminiscent of Lucky McKee’s May (2002). Here again, we get a socially awkward woman, Claire (Najarra Townsend), who desperately tries to emulate normal behaviour in order to fit in. While May kills in order to gather body parts to create the perfect friend, hairdresser Claire scalps her customers and wears their hair in order to take on their personalities. When one customer asks her to do her wedding hair, Claire begins to insinuate her way into Olivia (Brea Grant)’s life with increasingly awkward consequences which escalate to a final horrific act of violence. Befitting its title, Gevargizian’s movie is visually stylish (Robert Patrick Stern’s cinematography shimmers with saturated colours), but the pace drags and it feels somewhat repetitive, dissipating some of the tension.

Death Has Blue Eyes (Nico Mastorakis, 1976)

I’m not sure why I keep returning to Niko Mastorakis – maybe just because I have a perverse affection for his second feature, Island of Death (1976). Although prolific (and an inveterate self-promoter), he’s a fairly clumsy director with apparently no internal radar for detecting dumb ideas – exhibit A, Hired to Kill (1990). Death Has Blue Eyes (1976) was his first feature and it’s an incoherent, raggedly-paced mess. This was no doubt aggravated by having as much as forty minutes cut out by its distributor, but internal evidence from what remains suggests that more would not necessarily have fixed any of the glaring problems. Scenes drag on and then abruptly end without resolution as the movie jumps to something else which more often than not seems to have nothing to do with what we were just watching. Although some kind of story eventually emerges, there’s a strong who-cares factor because the main characters are so annoying – a pair of buddies who clumsily con their way around Athens and get involved with a young woman who has no memory but seems to possess psychic powers. She’s in the charge of an older woman, ostensibly her mother, who drafts the guys into helping because the two women are being pursued by some shadowy secret organization. Everything is just tossed in without much concern for how it hangs together, with a bit of nudity added for box office value.

The Invisible Man Appears (Nobuo Adachi, 1949)/

The Invisible Man vs the Human Fly

(Mitsuo Murayama, 1957)

Although Toho’s Gojira (1953) launched Japan’s very successful sci-fi/fantasy boom, it seems that it was Daiei a few years earlier which first tested the waters with a low-budget riff on a popular sci-fi trope – the antisocial possibilities of invisibility. Although there are some judiciously used effects courtesy of the great Eiji Tsuburaya, who would soon take his considerable talents to Toho, Nobuo Adachi’s The Invisible Man Appears (1949) is hampered by a rather pedestrian script about an unscrupulous businessman who hijacks scientists working on an invisibility formula in order to – well, not rule the world, but just steal a famous necklace which would be just as easily obtained through normal burglary. In fact, he probably would have been better off just pulling a conventional robbery because all the invisible man shenanigans just call attention to his plot. Apart from Tsuburaya’s effects, the best thing about the movie is that nifty title.

Eight years later, with Godzilla and his fellow monsters cleaning up at the box office, Daiei took another stab at the theme, though Mitsuo Murayama’s The Invisible Man vs the Human Fly (1957) is not actually a sequel – different scientists, different invisibility mechanism; instead of a chemical formula, this time it’s a harnessed cosmic ray. Although there are dangers, invisibility is enlisted in the investigation of a series of mysterious murders which turn out to be committed by a man shrunk to insect size with a secret formula created by military scientists towards the end of the Second World War. Though the effects work is uneven, the idea is absurdly entertaining (at one point the little guy climbs up the body of the woman he desires as she sleeps).

Both movies are pretty threadbare, with more emphasis on noir-inflected crime and nightclub scenes than on the fantasy elements, but as a minor, previously unknown sidebar to Japanese sci-fi, Arrow’s double-feature Blu-ray is a nice addition to the collection.

Double Face (Riccardo Freda, 1969)

Riccardo Freda had a four-decade career during which he worked in many genres. Perhaps his influence on other filmmakers outweighs the intrinsic value of his own work. Two films in particular form a partial bridge between the Italian Gothic and the giallo – The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (1962) and The Ghost (1963) – but one of his greatest contributions to cinema was providing the first opportunities for Mario Bava to transition from a successful career as cinematographer to director; this he did by walking away from both I vampiri (1957) and Caltiki The Immortal Monster (1959), leaving his cameraman to complete them.

Double Face (1969) has giallo elements, while also harking back to earlier psychological mysteries in which the protagonist is subjected to an elaborate plan to drive him mad. In this case, rather than a woman, the target is a businessman (Klaus Kinski) who has been tormented by his unfaithful wife and now finds himself suspected of her murder when she dies in a fiery car crash. He begins to suspect that she’s not really dead, a suspicion seemingly confirmed when he’s shown a porn film in which a woman very much like her appears (echoes of Fulci’s One on Top of the Other, made the same year). The resolution of the mystery is fairly predictable – someone greedy is determined to get their hands on an inheritance – but it’s interesting to see Kinski in a sympathetic, vulnerable role for once.

Nightfall (Jacques Tourneur, 1956)

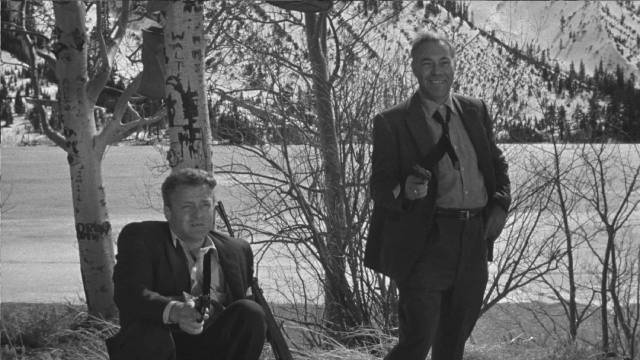

Nine years after making Out of the Past (1947), the greatest of all films noirs, Jacques Tourneur returned to the genre with this adaptation of a David Goodis novel. As you’d expect, Nightfall (1956) is an occasionally poetic, doom-laden story with a tentative romance at its centre. Slightly paranoid James Vanning (Aldo Ray) meets a woman at a bar who attracts him, but then immediately takes on shades of the femme fatale when it looks like she’s set him up for a couple of vicious thugs who think he stole a bag of loot from them. That misunderstanding is the result of a chance encounter in the snowy wastes of Wyoming, where the two men, fleeing after a bank robbery, run off the road and are helped by Vanning and his best friend who are on a fishing trip.

The robbers, John (Brian Keith) and his psychotic partner Red (Rudy Bond), kill the friend and leave Vanning for dead – but he recovers and just has time to flee as the bad guys return to the campsite after realizing they dropped the loot there. Dazed, Vanning had grabbed the bag, but he loses it in the snow. Suspected by the police of murdering his buddy, Vanning goes on the run because no one would believe his crazy story. Now, having narrowly escaped John and Red again, he turns for help in the only place he can think of, seeking out Marie Gardner (Anne Bancroft), the woman from the bar; although suspecting that she had been used as bait by the robbers, he’s decent enough to know that since he got away from them they might go after her.

Neither of them has a good reason to trust the other, but on the run together they form a bond and she helps him as he heads back to Wyoming, hoping to find the money and clear himself. On their trail, in addition to John and Red, is insurance investigator Ben Fraser (James Gregory), who is far from convinced of Vanning’s guilt. Everyone eventually ends up back in that snowy waste for a violent confrontation, which may well have influenced the Coen Brothers in Fargo (1996).

With a simpler narrative than Out of the Past, Nightfall has a leisurely pace and an emphasis on the essential decency of Vanning, Marie and Fraser. Even John finally gets tired of Red’s viciousness. Counter to the common trajectory of noir, decency triumphs and redemption is a real possibility, making Nightfall feel like a much slighter film than its predecessor, but the characters are engaging and Tourneur makes good use of the winter landscape.

Mill of the Stone Women (Giorgio Ferroni, 1960)

I’ve waited a long time to see a decent copy of Giorgio Ferroni’s Mill of the Stone Women (1960). Perhaps in recognition of that anticipation, Arrow have gone all out with their special edition. The two-disk set includes four different versions – on disk one, the 96-minute Italian and international, which are essentially the same cut but with alternate language tracks (Italian and English) and alternate titles; on disk two, the shorter French cut (90 minutes), which includes footage not in the other versions, and the American cut (95 minutes), which has an alternate English-language track and scenes moved around in a different order. There’s a Tim Lucas commentary, a video essay by Kat Ellinger, some archival interviews, and a booklet with essays and contemporary reviews. Essentially, they’ve gone from zero to sixty in no time flat in terms of an English-friendly presentation.

The only other movie I’ve seen by the prolific Ferroni is a fairy routine spaghetti western called Fort Yuma Gold (1966), so I have little context for Mill, which seems to straddle many strands of European filmmaking. Although an Italian production, its setting is the Netherlands, giving it a damp and gloomy atmosphere which seems more Germanic – an impression reinforced by several German cast members. The Gothic elements and saturated colours seem to bear a strong Hammer Films influence, while the supernatural elements are given a gloss of science. This echoes both Henry Cass’ Blood of the Vampire (1958) and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (released earlier in 1960); the French connection is strengthened by the presence of Dany Carrel as heroine Liselotte.

No doubt it was just a fortuitous confluence of influences, but Ferroni’s film was also released shortly after Roger Corman’s first Edgar Allan Poe movie, The Fall of the House of Usher (1960) – something was in the air as the ’50s gave way to the ’60s, infusing the Gothic with more sex and violence. Mill cinematographer Pier Ludovico Pavoni’s heightened use of colour also prefigures the lush, frequently artificial visual style in Mario Bava’s thrillers and horror films (although of course Bava had been using those techniques as cinematographer on other directors’ films before he began directing himself).

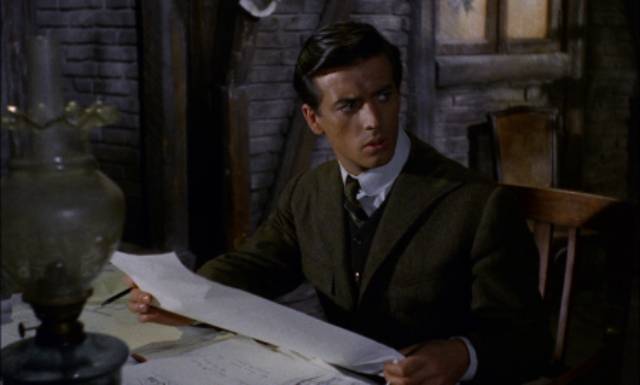

One other influence on Mill of the Stone Women, so obvious one might forget to mention it, is Michael Curtiz’s The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) and, more particularly, Andre De Toth’s 3D colour remake House of Wax (1953). A centrepiece of Ferroni’s movie is an animated display of famous women in history who were either tortured and executed or had committed murders themselves – figures which inevitably turn out to conceal the real dead bodies of women killed by the sculptor Professor Wahl (Herbert A.E. Bohme) and his collaborator Dr. Bohlem (Wolfgang Preiss), who have been draining victims’ blood to keep Wahl’s daughter Elfie (Scilla Gabel) alive – or rather repeatedly reviving her from death.

Their sinister scheme is gradually uncovered by Hans von Arnim (Pierre Brice), a writer who has come to the Mill to write a history of the famous carousel. He falls under the sway of the mysterious, somewhat ethereal Elfie who asks him to help her escape imprisonment, only to be horrified when a sexual encounter ends with her a seeming corpse. Hans is almost driven mad (with a strong push by Wahl and Bohlem), while his girlfriend Liselotte (Dany) is targeted as the next unwitting blood donor.

Mill of the Stone Women has a heady mix of cool, damp Northern atmosphere and erotic heat, with excellent production design by Arroyo Equini, and a touch of class added by conscious visual references to none other than Carl Dreyer – the opening sequence at a docking place on the bank of a canal, with a gallows-like signal bell and a windmill in the background, evokes the stifling, dreamy atmosphere of Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932). Ferroni has been overshadowed by more famous names, but Mill of the Stone Women deserves recognition as a significant contribution to the evolution of Euro-horror at the beginning of the ’60s, and can stand on its own merits as a fine example of Gothic cinema. Arrow’s excellent, comprehensive edition should ensure its permanent rescue from obscurity.

Comments