Vinegar Syndrome closes out 2022

I haven’t yet shaken off my penchant for watching cheap horror movies, having recently received the final shipment from my 2022 Vinegar Syndrome subscription. Although there were a few interesting – at least entertaining – titles in the bundle, there was a preponderance of trash which will no doubt help me make a rational decision when subscription renewal time arrives in January. VS ended the year by unearthing some bottom-of-the-barrel ’80s slasher movies and I have to wonder why they bothered. Even completists must have their limits, but apart from ticking a few more titles off the list, I find it hard to imagine anyone being particularly entertained by these, count ’em, four new releases. (But, yes, I did watch them all!)

One of the most formulaic of all genres, if the slasher has any value at all it lies in the originality of individual details. If even the details are tiredly familiar, the movie is as dull and rote as the cheapest B western churned out by a poverty row studio. While there are occasional moments of invention, the four movies which just arrived are mostly just tedious reiterations of overly familiar elements, and the occasional indication that the filmmakers are well aware of this doesn’t actually make things better.

Evil Laugh (Dominick Brascia, 1986)

That awareness is most apparent in Dominick Brascia’s Evil Laugh (1986), which includes a nerdy character who reads a prominently displayed copy of Fangoria with a Friday the 13th sequel on the cover; here, ten years before Wes Craven’s self-referential Scream (1996), we have a character who is aware of the kind of movie he’s in and tries to persuade his companions of the danger they’re facing – warnings which they naturally ignore at their own peril.

A group of med students arrive at a remote house to help their mentor fix it up because he plans to buy it and re-establish it as a home for needy foster kids. They’re puzzled that he’s not there to greet them, but we know that he’s already fallen victim to the masked killer lurking around the property. In the movie’s most original detail, the fresh “cow’s heart” which is sitting with the groceries on the kitchen counter, and which is soon cooked up for supper, was actually cut out of the host’s chest by the killer.

As the night drags on, we learn that ten years ago a bunch of foster kids were slaughtered in the house by a mentally deficient handyman. Is he back to continue his murderous rampage? That Fangoria cover hints at the final revelation which comes after almost everybody has died. Along the way, there are occasional visual gags between the routine killings, but mostly it’s the usual slasher filler, with characters bickering and pairing off for sex before being killed.

For some reason, VS gives this one a stand-alone release, with a commentary track and feature-length retrospective making-of. The other three new releases come in a box set, volume two of Homegrown Horrors, which is a disappointing follow-up to last year’s quirky set. That one was uneven, but at least you felt that someone had made an effort to dig up obscure but interesting movies … this new set feels like they just dipped into a discount bin at a corner video rental store and grabbed a handful at random. There’s none of the weirdness of Winterbeast or the imagination of Beyond Dream’s Door. The new trio are closer to that set’s weakest movie, Fatal Exam, but mostly lack even that one’s occasional bright spots.

Moonstalker (Michael O’Rourke, 1989)

Moonstalker (1989) has all the requisite elements, but fumbles the execution. Its most interesting aspect is that having set up an obvious Final Girl in the opening act, it casually disposes of her and moves on to an entirely new group of potential victims in act two. The movie begins with a family camping in a bleak area in the middle of winter – mom and the two kids are unhappy, but dad insists it’s a great opportunity to get away and commune with nature. A scruffy old coot pulls into the campground and tells them about the area; what they don’t realize is that he has his crazy son chained up in his trailer and that night he lets the kid loose to go and steal the family’s microwave … which he does after slaughtering everyone except the daughter with an axe.

After chasing her through the snowy woods, he stops and kills a passing driver and runs her down on his way up to a wilderness training camp where a bunch of counsellors have just arrived to take the course run by a jerk who obviously hates them all. Naturally, they pair off, take midnight showers, make out … and get killed off singly and in pairs. The problem is writer-director Michael O’Rourke’s inability to pace things and, worse, he misunderstands the most basic technical issues. He uses the de rigeuer killer POV frequently, but there’s no attempt to imply that the POV is that of some unknown figure watching from the shadows. We’ve seen the killer clearly, know who he is, even know what motivates him, and the camera representing his position is always completely out in the open and often only a few yards from characters who ought to be able see him.

This clumsiness is compounded by the fact that, while everyone is in tents closely set up in a small campground, no one can hear people screaming as they’re attacked by an axe-wielding maniac a few yards away. No attention has been paid to how to stage anything, each moment conceived in complete isolation from the rest and then shot and edited sluggishly. And yet there are two commentary tracks and two feature-length making-of docs!

Dead Girls (Dennis Devine, 1990)

And yet Moonstalker is the best of the bunch. Dead Girls (1990) is the second feature by Dennis Devine, who has been churning out cheap exploitation movies for over thirty years – I guess there are niches still completely unfamiliar to me because this is the first one of his movies I’ve come across. It doesn’t bode well that this is supposedly one of his best. Again, he lays out the familiar elements of the genre and perhaps paces things better than O’Rourke, but where it falls really short for me is that it revolves around a rock band but does nothing with the music. Why do filmmakers do this? Coming on the heels of Vinegar Syndrome’s release of Hard Rock Zombies and Slaughterhouse Rock, this suggests that there’s a whole sub-genre which fails to provide the one thing it promises to give the audience that sets it apart from all the other generic movies. Why make a music-centric movie when you don’t have the means (or talent) to provide the music?

Dead Girls are a band whose “death metal” has apparently inspired group suicides, one surviving victim being lead singer Gina’s sister. Needing to rethink her career, Gina persuades the band to go on a two-week retreat to a cabin by a lake where they can figure out what to do next, and maybe help the sister (who tags along with her nurse) to recover. As the band members bicker and argue (are really good friends with harmonious relationships ever targeted by maniacs?), a masked figure stalks and kills them, leaving an envelope with the lyrics of one of their songs at each murder scene, and sowing seeds of internal distrust – eventually the band members become paranoid and begin killing each other. You can give Devine a bit of credit for complicating the plot with that twist, though there’s no big surprise when the initial killer is unmasked. But why don’t we ever really hear any of the music which is supposed to have triggered all the death? (Two commentaries and yet another feature-length making-of)

Hanging Heart (Jimmy Lee, 1983)

Compared to the third movie in the set, though, Moonstalker and Dead Girls are paragons of competence. Korean filmmaker Jimmy Lee supposedly graduated from the American Film Institute, but judging by Hanging Heart (1983) it appears he must have slept through all his classes. The level of incompetence here is painful to see – not perhaps on a technical level (it’s quite slick visually, with occasional striking images), but in its complete inability to tell a coherent story or even to understand what a story is.

In outline, there’s nothing too difficult to comprehend: a young actor in an experimental play lingers in the theatre after rehearsal to have sex with his girlfriend on stage, and returning from a quick shower finds her dead. Seen holding the body by the janitor, he is arrested and charged with murder, but gets out on bail. Then he’s caught with another freshly murdered woman, cementing the opinion of the police and the prosecutor that he’s a murderous psycho. Put on trial, he’s defended by a lawyer who obviously is sexually obsessed with him, leading to an unsurprising climactic revelation of who the masked killer actually is.

How this threadbare narrative is rendered incomprehensible by Lee is something to behold – or would be, if it wasn’t so damned boring. Lee has no grasp of the most basic mechanics, beginning with the way a police investigation and trial work. Our hapless protagonist is arrested after the first murder and immediately put on trial … and yet the cops and prosecutor are urgently trying to unearth evidence to prove his guilt at the same time … while he’s out on bail and getting caught up in a second murder during the trial … and still being let out on bail, because there’s no proof, just circumstantial evidence which won’t be enough to convict him… It’s all dizzyingly non-sensical. Why does writer-director Lee try to stage a trial at all when all he needs are the uncertainties of a hostile police investigation to put the hapless protagonist in jeopardy? Anyone who’s ever seen a TV show about lawyers knows that the trial doesn’t start until the investigation is done, so what was Lee thinking?

He obviously has other interests than narrative plausibility. All the glossy, lingering homoerotic imagery gives the movie the feel of gay porn (or at least a David DeCoteau movie) which has had the money shots edited out to make it more mainstream. But even this impression is conflicted because the homoerotic tone is undermined by the climactic homophobic revelation of the killer’s identity and motivation.

The porn ambience is amplified by the quality of the acting, particularly Barry Wyatt as the lead, who spends most of his time near-catatonic as he relies on the display of his body to express character. It’s not surprising that this was never released in the U.S. either theatrically or on home video until VS inexplicably dug it up and gave it a 4K restoration from the original negative and put it on disk with more than an hour of cast and crew interview featurettes. All this effort seems incomprehensible to me given how awful the movie is.

*

Invisible Maniac (Adam Rifkin, 1990)

The rest of Vinegar Syndrome’s year-end batch were mostly more satisfying – well, except for Adam Rifkin’s Invisible Maniac (1990), which just as inexplicably gets a dual-format 4K UHD/Blu-ray release. This is like a nudie-cutie from 1960, which means it’s a lame comedy excuse for a bunch of gratuitous nudity. A crazed scientist escapes from an asylum and gets a job at a high school where he uses his invisibility formula to spy on the girls’ showers and murder anyone who mocks him for being an annoying jerk. Clumsy and unfunny, the only point of note is how well a few of the actors mime being beaten up by their unseen assailant. (Two commentary tracks, half-hour making-of, deleted scene, archival interview with Rifkin, and a music video)

Sworn to Justice (Paul Maslak, 1996)

Things improved from there, with even Paul Maslak’s Sworn to Justice (1996) being entertaining despite its clumsy execution. This is largely thanks to the presence of Cynthia Rothrock (who also co-produced), who honed her on-screen martial arts skills in Hong Kong and displays her appealing presence here even though the fight scenes are not very well–staged and overly edited. She plays a psychologist who becomes a vigilante after her sister and nephew are killed by a gang, testifying in court cases by day and kicking ass by night. The twist is that a head injury has awakened psychic powers which enable her to get glimpses of the criminals when she touches certain objects, leading her up through the ranks to the not-very-surprising Mr. Big behind it all. (Multiple new and archival interviews, plus an archival making-of featurette)

Santo vs Dr. Death (Rafael Romero Marchent, 1973)

Then there’s Rafael Romero Marchent’s Santo vs Dr. Death (1973) in which Mexico’s most famous masked wrestler is sent to Spain by Interpol to investigate an international art thief. I haven’t had much experience with the lucha libre genre and it’s obviously a bit of an acquired taste – you have to be willing to accept that the hero wanders around in public at all times in a suit and silver mask, which he doesn’t even have to remove when passing through customs – but the absurdity is part of the charm. There’s apparently often a fantasy element and here that’s provided by the villain’s lab where he makes exact copies of the masterpieces he’s stolen, using a process which involves inducing tumours in his models which, when ripe, he surgically removes to extract the secret ingredient, disposing of his victims’ bodies in a pool of acid beneath the lab. (I’m now looking forward to Indicator’s two-disk set of the first two Santo movies due for January release.) (Spanish and English audio options, plus a video essay on Santo)

Burning Paradise (Ringo Lam, 1994)

Something which seems quite out of the norm for VS is Burning Paradise (1994), the sole period martial arts movie made by Ringo Lam, one of the finest action directors from Hong Kong’s golden age in the ’80s. Harsher and less romantic than John Woo, Lam made a series of visceral and influential masterpieces from City on Fire (1987) to Full Contact (1992) before branching out with a number of Jean-Claude Van Damme movies in the ’90s and early ’00s. Though I’ve seen quite a few of his movies, I wasn’t even aware of Burning Paradise until this release. Beginning with the destruction of Shaolin Temple by Manchu forces (a very common genre starting point), it follows student Fong Sai Yuk (an equally familiar genre figure) into captivity in the Red Lotus Temple, where the surviving monks are held as slaves labouring in an underground workshop. Lam’s handling of the action sequences is impressive, from the early confrontation between Fong and an entire Manchu army in the desert to the various individual fights in the Temple. There’s an evil Manchu general, a feisty heroine, mistaken motives and various degrees of self-sacrifice, the style quite obviously influenced by producer Tsui Hark, whose Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) is echoed in some of the action sequences. Apart from the period trappings, the main thing which distinguishes the movie from Lam’s grim contemporary thrillers is the occasional intrusion of awkward comedy bits which distract from the otherwise relentless narrative. (Commentary, video essay, and a couple of interviews)

Freeway (Matthew Bright, 1996)

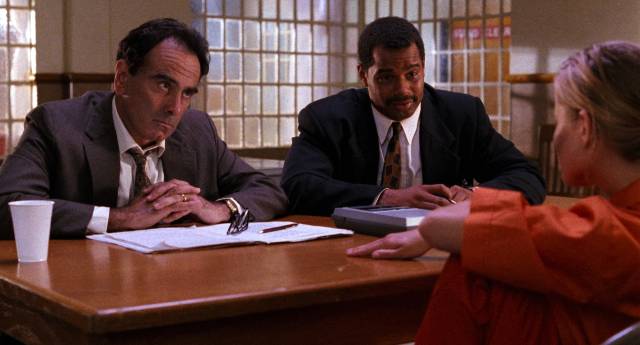

I saw a lot of movies back in the day, but somehow Matthew Bright’s Freeway (1996) escaped my notice. Although not entirely successful, its day-glo colours, archetypal narrative tropes and lead actors on the cusp of stardom ought to have made it stand out. Not sure why it didn’t. Perhaps it was the oddball tone, though normally that would have been a draw for me. Updating Little Red Riding Hood into a black comedy about delinquency and serial murder is rather high concept and on the whole writer-director Bright carries it off audaciously, but what really makes it work is the lead performance from a young Reese Witherspoon as the abrasive, illiterate trailer trash daughter of a hooker (Amanda Plummer) and abusive stepfather (Michael T. Weiss); when both parents are arrested, Vanessa gives her social worker the slip and heads North in search of grandma’s house.

Her car breaks down and she’s given a ride by a helpful guy named Bob Wolverton (Keifer Sutherland), apparently a social worker himself, who asks probing questions which get increasingly, uncomfortably personal until Vanessa finally realizes that he’s the serial killer who’s been on the news recently. Luckily, she has the gun her boyfriend gave her for protection and she gets Bob to drive off the freeway in a remote spot, where she shoots him in the face and then empties the gun into his back before driving off in his van. But Bob somehow survives (though his face is a mess and he’s partially crippled) and she’s quickly arrested for attempted murder.

No one believes her story about Bob being the killer and her abrasive attitude doesn’t win her any friends, so she’s locked up awaiting trial. Vanessa is no sweet victim, but rather just as sociopathic as Bob, violent and foul-mouthed. By the time she’s back on the road, the police have realized that Bob actually is the killer, but he’s disappeared. All paths converge at grandma’s house (or rather at her trailer in a trailer park), but when Vanessa discovers Bob hiding under the covers in grandma’s bed, once again he proves no match for the mean girl.

I’m not sure that Bright has any point to make other than the revisionist transformation of Little Red Riding Hood into someone self-sufficient and far more dangerous than the wolf, but even with some graphic violence, the storybook ambience and Witherspoon’s performance (supported rather than matched by Sutherland’s) make Freeway an entertaining black comedy. (Dual-format 4K UHD/Blu-ray edition with two commentaries, multiple new and archival cast and crew interviews, archival video press kit and behind-the-scenes footage)

Road House (Rowdy Herrington, 1989)

Rowdy Herrington’s Road House (1989) is another movie I hadn’t seen before VS’s deluxe dual-format release, though in this case I had heard of it – I’d just never had any interest in seeing it. Patrick Swayze is not an actor who particularly interests me and the lingering image of Dirty Dancing (1987) skewed my impression of Road House. Having now seen it, I have to say that it’s a petty good slice of dumb entertainment, with its roots back in Phil Karlson’s Walking Tall (1973) – that is, it’s a well-made piece of redneck action. Swayze plays Dalton, a renowned bouncer with a dark secret in his past, who’s hired by Tilghman (Kevin Tighe), who owns the Double Deuce bar in a small town. The place is a grubby dive full of violent patrons and Tilghman wants it cleaned up. Enter Dalton, who spends a night or two sussing things out before making staff changes and disciplining the unruly customers.

There’s push-back; his car is vandalized and he’s knifed – the latter leading to a meet-cute with local doctor Doc (Kelly Lynch). As he gradually gains respect and the bar becomes a success, he also draws the attention of crooked businessman Brad Wesley (Ben Gazzara), who considers the town his own. A feud develops and violence escalates; Dalton’s old mentor Wade Garrett (Sam Elliott) arrives to lend a hand and ends up dead, which finally unleashes Dalton’s dark side. Doc sees him kill Garrett’s right-hand man with his bare hands and he has to confront the violence inside himself as he heads for the final showdown with Garrett.

The idea of a bouncer as the hero is amusing; the fight scenes are satisfying; the romance predictable; and the escalating conflict between the troubled outsider and the local kingpin provides an effective narrative spine. There’s even a decent musical accompaniment provided by the house band – played by the Jeff Healey Band. Road House is structured according to the standard playbook, hitting all the requisite emotional cues, given a nice polish by Herrington and cinematographer Dean Cundey, and played by a cast who know exactly what’s required of them. I probably never would have sought it out if not for this release, but having finally seen it, I have to say I was entertained. (Dual-formal 4K UHD/Blu-ray edition with two commentaries, several new cast and crew interviews, plus a second Blu-ray of archival interviews and making-of featurettes)

Comments