William Castle’s horrors from Indicator

William Castle had a long career as a director and producer-director. Many of his movies were money-makers, popular with audiences, and he became a beloved personality to his fans. But the only real critical respect he ever received was for Rosemary’s Baby (1968), a movie he really, really wanted to direct, but which he ended up only producing when Paramount head of production Robert Evans (who died a few weeks ago) convinced him to hand it over to Roman Polanski. This, Castle recognized, turned out to be a smart decision – Rosemary’s Baby is a bona fide classic far beyond the level of Castle’s own movies.

From his directing debut in 1943, Castle was a prolific B-movie maker, turning out almost forty low-budget features in fifteen years – some of them pretty good (mysteries and noirs), one even in 3D (the western Fort Ti [1953]), many for Harry Cohn at Columbia. But he remained somewhat insecure about his work, and in the late 1950s began to put a lot of effort into promotional gimmicks to pull in audiences, eventually actually building them into the movies. He was, as many have said, a showman who used carnival barker methods to sell tickets to the rubes.

At a distance of six or seven decades, we no longer have any direct access to Castle’s gimmicks (unless there’s an isolated revival at a festival or a repertory theatre), so our experience of his movies lacks the original communal thrill generated by his promotional hype. On their own, the movies reveal Castle to be an efficient craftsman less concerned with stylistic flourishes than with getting the work done without spending too much money. He did have a knack for finding entertaining stories but, in his best movies, the intrusion of the gimmick now seems to undercut and trivialize some quite effective accomplishments. What once lured the kids in, while it does have some historical charm in itself, now deflates the climaxes of these movies.

Indicator released two box sets of Castle’s movies last year and recently I finally got around to watching the first – four of his most successful from when he returned to Columbia as an independent producer in the late ’50s. Three of them have their gimmick embedded in the movie itself, while his most famous unfortunately can no longer be experienced as intended because it required physical apparatus to be installed in the theatres showing it.

*

13 Ghosts (1960)

13 Ghosts (1960) was Castle’s fourth collaboration with writer Robb White, and it’s probably the least of them. A throwback to the old dark house genre which was already getting creaky in the silent period, it mixes comedy and mystery with what turns out to be an extraneous supernatural element – the ghosts of the title have nothing to do with the plot other than to provide a crook with a device to scare people away from a mansion reputed to contain a hidden treasure.

When reclusive Dr. Zorba dies, he leaves his gloomy old house to nephew Cyrus Zorba (Donald Woods), an impoverished academic. Cyrus and his family have to move in to claim the inheritance, with the condition that they can’t sell the place, which is now home to the titular ghosts which Dr. Zorba collected from around the world. The nice young lawyer who’s handling the estate (Martin Milner) warns them about the risks … and makes a play for teenage daughter Medea (Jo Morrow), while befriending little brother Buck (Charles Herbert). There’s no mystery about the lawyer’s nefarious intentions – he knows the old doctor liquidated all his assets and hid the money in the house – so when a particularly physical apparition menaces Medea one night its actual identity is pretty obvious, especially since it bears no resemblance to the “real” ghosts who inhabit the house.

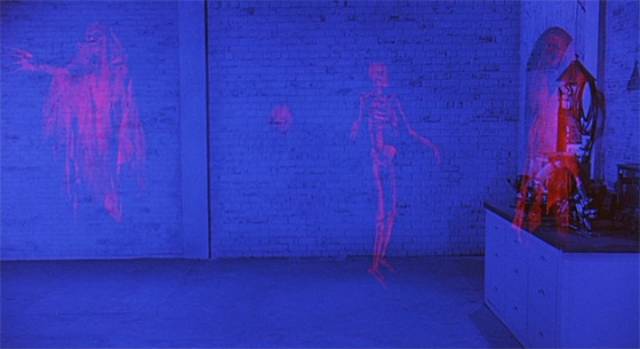

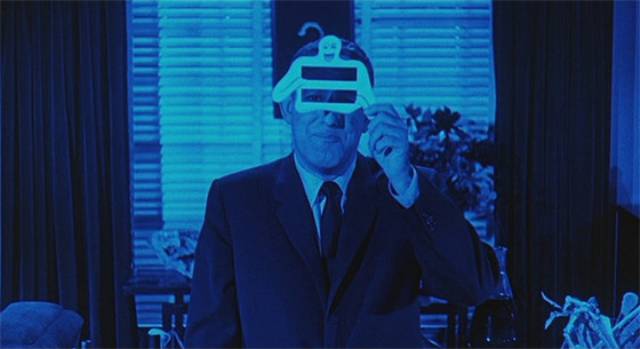

Those ghosts are Castle’s gimmick this time out, manifesting through a variation on the old anaglyph 3D technique which uses two different coloured lenses to separate parts of the projected image. In this case, Illusion-o provided audiences with a “ghost viewer” which offered the option of a red or blue filter through which to watch certain scenes in the black-and-white movie: the red filter revealed the ghosts, the blue concealed them. The main problem is that the ghosts provide nothing but extraneous spectacle – the movie essentially stops dead to display them, sometimes at tedious length, as when Buck sees a headless lion tamer and his lion doing their act in the basement. The ghosts are there, but they’re not frightening nor interesting in themselves, and have no impact on the narrative except at the end when old Dr. Zorba takes care of the villain.

Indicator has gone all out with this movie, offering no less than four viewing options. There’s a plain black-and-white version, with the ghosts simply superimposed; there’s the Illusion-o version, with the ghost scenes tinted blue and the ghosts themselves superimposed in red; and then there are two versions digitally simulating the ghost viewer effect. These latter present the ghost scenes through murky colour “filters”, red to reveal the spooks, blue to hide them – though in the latter they are discernible as faint shadows.

*

Castle strove to become a recognizable personality like Hitchcock by injecting himself into his movies; but not in subtle cameos. He transferred Hitchcock’s jokey host from the Alfred Hitchcock Hour TV show to the big screen, appearing at the beginning and end of his movies (and sometimes inserted somewhere in the middle) to introduce the story and the gimmick. While he came across as amiable, he lacked Hitchcock’s wry humour and his presence again somewhat undercuts the movies’ potential to generate actual suspense and horror.

His next two features ditched the supernatural element for psychological horror and both are the better for it.

*

Homicidal (1961)

Rather too heavily influenced by the previous year’s success of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Homicidal (1961) is nonetheless one of Castle’s best movies, even more explicitly rooted than its higher profile predecessor in gender confusion. There are numerous visual references to Hitchcock’s film and you might kindly see them as homage. Like Psycho, Homicidal begins in the city and moves to a small town where a twisted family history results in murder, but Castle’s opening is more shocking than Hitchcock’s.

Emily, a frosty blonde (Joan Marshall), checks into a seedy hotel and offers the bellhop a strange proposition: she’ll give him $2000 if he meets her at midnight and marries her, the marriage to be annulled immediately after the ceremony. Although there’s something obviously peculiar about this, the guy agrees – that’s a lot of money. So at midnight they get in his car and drive across town to a justice of the peace. Again, she gets her way by offering money to get the justice out of bed to perform the ceremony. The annulment takes the form of a sudden and shocking murder as Emily repeatedly stabs the justice in the belly with a long knife.

Leaving her groom and the justice’s wife in shock, Emily takes the bellhop’s car and drives away, switching to her own car which she has left parked ready for her getaway. She calmly drives away from the city to the small town where she lives with an elderly invalid named Helga (Eugenie Leontovich). The wheelchair-bound woman has been left unable to speak by a stroke and obviously lives in fear of Emily, who was hired as her caretaker by the house’s owner, an odd man named Warren (“Jean Arless”).

It turns out that the name Emily used for her murderous visit to the city belongs to Warren’s half-sister Miriam Webster (Patricia Breslin) and the cops come to town looking for her. The bellhop clears Miriam, but a sketch in the paper looks a lot like Emily, raising the suspicion of Miriam, her boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett) and Warren himself. And Emily seems to be becoming more unhinged and dangerous (she wrecks Miriam’s flower shop and beheads Helga).

(Spoiler) On a first viewing, despite there being something obviously strange about Warren, the climactic revelation comes as a surprise. Emily and Warren are the same person, twisted by a monstrous childhood in which a female child was disguised and raised as a boy in order to satisfy a father’s desire for a male heir. On the brink of inheriting a fortune, Warren has set out to kill the only people who know his secret – the justice of the peace who forged the birth certificate and Helga, who oversaw the birth and helped “his” mother create and maintain the deception.

Warren is a girl forced to grow up as a boy, who has now created a murderous female persona to protect his false identity. The layers of that identity are carefully structured in Robb White’s script and Joan Marshall pretty much carries off the dual role of Emily and Warren, though Warren is strangely unsettling in his ambiguity.

Homicidal is one of Castle’s most accomplished movies, its inherent perversity making it one of the best post-Psycho psycho thrillers. But Castle’s need to shoe-horn a gimmick in to sustain his own reputation undercuts the ending by turning the climactic revelation into a gag. As Miriam, now aware of the threat Emily poses, approaches the house, Castle inserts a 45-second pause – the “fright break” to allow people who are too scared to face the horror to leave the theatre and get their money back – so that the suspense has been broken, turning the revelation of Emily’s true identity into a throwaway moment.

*

Mr. Sardonicus (1961)

After several years of working closely with Robb White, Castle found a new writer while reading an issue of Playboy at poolside while vacationing in Hawaii. Immediately after reading a story by the magazine’s fiction editor, Ray Russell, he got on the phone and secured the rights, hiring Russell himself to write the script. Mr. Sardonicus (1961) was a departure for Castle – although he’d previously made westerns, most of his movies were contemporary; this was his first period horror movie, with echoes of the classic Universal horrors, Val Lewton’s moody RKO B-movies, and even Mario Bava and Roger Corman’s recent Gothic horrors. But Castle could only sporadically achieve the kind of atmosphere which distinguished all those models. Cary Odell’s art direction and Burnett Guffey’s cinematography give the film an effective Gothic look, but here, separated from contemporary settings and characters, Castle’s stylistic limitations are more apparent – he had a perfunctory technique whose chief aim was to get the actors in front of the camera saying their lines with as little fuss as possible.

But even given this, Mr. Sardonicus is one of Castle’s better movies, thanks to Russell’s perverse script and an excellent cast. In 1880, a successful London surgeon, Sir Robert Cargrave (Ronald Lewis), is summoned by former love Maude (Audrey Dalton) to her home in a remote Eastern European castle, where she lives in fear of her husband, Baron Sardonicus (Guy Rolfe). When Cargrave gets there (like Jonathan Harker in Dracula, he’s warned away by frightened locals), he discovers that the Baron is cursed with frozen face muscles, which give him a permanent monstrous smile (influenced by Conrad Veidt’s Gwynplaine in Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs [1928]), which makes speech difficult and forces him to eat by slurping runny gruel from a bowl.

Sardonicus is a bitter, cruel man who demands that Cargrave cure him … or he’ll do something monstrous to Maude. The doctor orders equipment, sets up a lab, and starts experimenting on dogs with dangerous drugs, while rekindling his romance with Maude. It’s quite late in the movie before we learn why she ditched Cargrave and disappeared to marry a man whom she obviously has no feeling for other than fear – the Baron essentially bought her from her father who was facing financial ruin; she sacrificed herself to save her dad from exposure and humiliation.

The best part of the movie is the flashback in which we discover the origin of the Baron’s affliction. A peasant farmer married to a greedy, abusive wife, he learned only after his father’s death that the old man had a winning lottery ticket buried with him. Wanting to satisfy his wife’s material demands, he went to the graveyard at night and dug his father up, the sight of the corpse’s death rictus so terrifying that his own face froze into a replica of it. Hideously deformed but suddenly very rich, he bought a title and estate and renamed himself Sardonicus, mocking his own affliction.

Realizing that the Baron’s problem is purely psychological, Cargrave fakes a dangerous treatment to shock him back to normal. It seems to work and Sardonicus allows Maude to leave with the doctor. As they wait for their train, the Baron’s creepy servant Krull (Oscar Homolka) shows up to call the doctor back; although the Baron now looks normal, his face is still frozen and he can’t open his mouth to eat or drink. Cargrave explains that his treatment was a fake, that the Baron’s mind effected the cure and that he just needs to understand this in order to unlock his muscles.

At this point, Castle once again interrupts the narrative flow, reappearing on screen to conduct the “punishment poll” by having audience members hold up glow-in-the-dark cards showing either thumbs up or thumbs down to determine the Baron’s fate. The movie’s publicity claimed that there were two endings and which one was shown would depend on how the audience voted – thumbs up, the Baron would be spared, thumbs down he would be doomed. Of course, no audience would vote to spare him and there was actually only one ending. But it’s a good one. When Krull gets back from the station, he looks at the man who has long tormented him, thinks for a moment and decides to tell the Baron that he missed the doctor and there’s nothing to be done. He starts stuffing his face as Sardonicus realizes he’s going to starve to death.

Mr. Sardonicus (shouldn’t it have been called Baron Sardonicus?) has some gratuitous nastiness – particularly a couple of scenes in which a serving girl (Lorna Hanson) is subjected to leeches, supposedly to determine whether the blood suckers might ease the Baron’s problem. But for the most part it’s an effective mix of the Gothic with psychological horror, performed by an excellent cast. Lewis does what he can with the stolid hero role, Guy Rolfe and Oscar Homolka make the most of their creepy bad guys, and Audrey Dalton is quite charming as the put-upon, self-sacrificing heroine. In the flashback, Vladimir Sokoloff and Erika Peters, although only given brief screen time, flesh out the Baron’s background as his father and wife, supplying some sympathy for what he was before circumstances so drastically changed him.

*

The Tingler (1959)

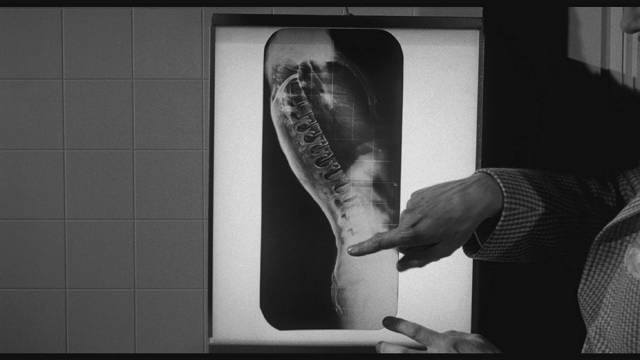

The earliest film in the set is also Castle’s best-loved movie, a film which embraces absurdity with enthusiasm and which also featured Castle’s most audacious gimmick. Robb White’s script for The Tingler (1959) hangs on a silly concept – an ill-defined creature lurks inside all of us, dormant until we experience intense fear, at which time it grows into a large lobster-centipede which grips the spine from butt to neck, crushing the vertebrae with its monstrous claws … unless you scream really hard to drive it away. Dr. Warren Chapin (Vincent Price) has been searching for proof of its existence for years and now he seems to have caught it on an x-ray.

By coincidence, he’s just met the mild-mannered Ollie Higgins (Philip Coolidge), who owns a movie theatre with his wife Martha (Judith Evelyn) which runs only old silent films (Henry King’s Tol’able David [1922] plays to packed houses!). Their meeting gives some idea of the ways in which the movie throws plausibility out the window from the start: Dr. Chapin is performing his pathology duties at the local prison by doing an autopsy on a just-hanged murderer when Ollie wanders in and introduces himself as the brother-in-law of the condemned man. He’s just been to witness the execution and wondered what they do with the body. Ollie and the doctor chat while Chapin slices up the corpse, and then Chapin offers Ollie a ride back to town.

Dropped off in front of the theatre, Ollie invites Chapin for coffee in the flat upstairs and the doctor meets Martha, a frightened, suspicious woman who happens to be a deaf-mute. She clings protectively to the money locked in a safe, watching Chapin distrustfully. Oddly, no one ever again mentions her executed murderer brother. Her inability to make any sound turns out to be important because, remember, the only way to save yourself from death-by-Tingler is to scream – your screams either shrink the critter back to its dormant state or kill it. In the movie’s centrepiece sequence, Martha is pursued about the flat by monstrous apparitions, literally scared to death.

White’s script has established some ambiguity about Chapin and his obsession and it’s possible that he has engineered Martha’s death to further his experiments. Before we learn the truth, the doctor has managed to extract a living Tingler from her corpse … Ollie has brought her body to the lab, and after extraction Chapin tells him to take her home and call the police. How he’s supposed to explain the fact that she’s been sliced open is left unaddressed.

After being attacked by the powerful parasite, Chapin realizes he’s messing with things best left alone and he takes it back to the theatre, planning to reinsert it into Martha’s body because that may be the only way to kill it. Unfortunately, it escapes its carry-case and slips through a vent into the theatre below. Here’s where Castle’s gimmick, Percepto, comes into play: in theatres showing the movie, small motors had been attached to the bottom of some seats and when the Tingler gets into the theatre, the protectionist would throw a switch, subjecting audience members to a surprise shock to the butt. At the same time, Chapin (for some inexplicable reason) turns off the house lights and the screen goes black as Vincent Price addresses the (real) audience, urgently telling them to scream for their lives. It’s all pretty meta for a goofy B-movie, taking the movie theatre trope from The Blob (1958) and pushing it a step further.

The Tingler is absurd, but the cast give committed performances – Price is very good at delivering nonsense dialogue with unironic conviction, and Judith Evelyn elevates the movie with her convincing terror. Castle amps up the sequence of her murder by injecting red blood into the black-and-white image. The Tingler itself is an amusing creation, stiff and pulled along by wires. Castle has no concern for plausibility, but except for the climactic gimmick, he does play it all quite straight. Still, there’s really no expectation that anyone above the age of eight will find any of this scary – it’s horror as fun and it’s undeniably entertaining. (To see a similar idea rendered with genuine gravitas, see Peter Newbrook’s The Asphyx [1972].)

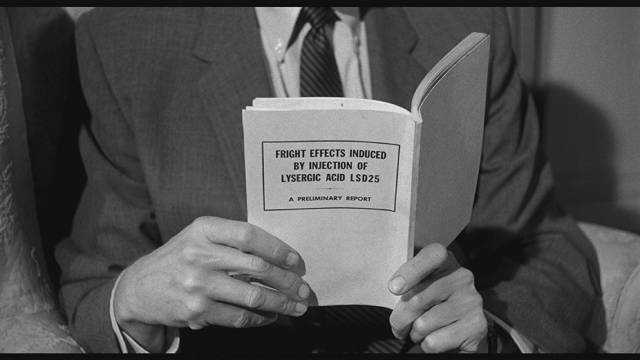

One final point of interest is that The Tingler was the first movie to explicitly feature LSD. Hoping to experience the Tingler himself, Chapin injects the drug, triggering a very bad trip – affording Price an opportunity to go over the top in his inimitable manner. Not only is the drug referred to as “acid” in the dialogue, Chapin is shown reading a monograph on the uses of LSD25 (which for some odd reason has the title printed on the back cover, rather than the front). So perhaps Castle was hipper than his goofy square image suggested!

The Tingler may not be Castle’s best movie (I’d rank both Homicidal and Mr. Sardonicus above it), but it is his most entertaining.

*

Indicator has done a fine job with these four key Castle features, comparable to their Hammer Films box sets. If I had one quibble, it’s that they included 13 Ghosts rather than either Macabre (1958), Castle’s first independent production and the one which launched his gimmicks (providing every audience member with a $1000 Lloyd’s life insurance policy to be paid if death occurred while watching the movie), or House on Haunted Hill (1959), the movie which, along with the previous year’s The Fly, launched Vincent Price’s hugely successful horror star career.

The set includes three commentaries (13 Ghosts doesn’t get one), numerous featurettes and interviews, and – best of all – Jeffrey Schwarz’s feature-length documentary about Castle, Spine Tingler! The William Castle Story (2007), an engaging account of the filmmaker’s life and work which paints a portrait of him as an amiable self-promoter who was never able to get over his insecurity about the value of what he was doing.

Comments